Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

Linda Wallace, eurovision

During the 1990s, the digital storage medium of the CD-ROM became a platform for artistic experiments in interactive form and participation. Accompanied by a boisterous technophilic rhetoric proclaiming the promise of liberation from passive media consumption, desktop multimedia (followed swiftly by the internet’s plethora of personal publishing systems) promised the digital avant-garde a new set of tools to cut up and into prevailing commercial narrative forms, as well as cheap, global strategies for distribution. Interestingly in the late 1990s, the consumer availability of digital video cameras and more recently the viability of large scale digital video storage through the DVD-ROM did not capture artists’ imaginations in the same way. Admittedly the libertarian hype about digital media has worn thin and, in many cultural theory and production contexts, given way to a more measured and critical assessment of the ‘newness’ of forms made possible by digital production. Nevertheless, there are relatively few examples of rigorous artistic investigations into the formal, technical possibilities and aesthetic implications of digital video.

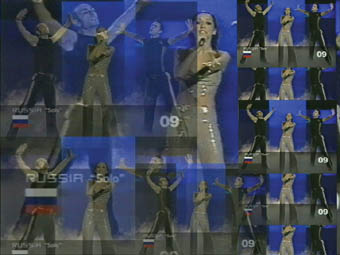

Linda Wallace’s eurovision video work, completed in 2001, is a notable exception. Confounding genre specification and therefore implicitly resisting relegation to either digital or time-based media, it boldly announces its status as a ‘linear version of an interactive’ project. And it is precisely this montaging of form that allows eurovision to become an exploration of how visual digital operations—slicing images into each other, pulling them through the grid of the screen transforming them into information, and their slippery layering—might impact upon the temporality of video. Of course video has itself been subjected to a thorough temporal shakedown over the last 30 years, not least by the experiments with corporeal rhythm and duration by Bill Viola, Gary Hill and others. But many of these experiments have taken place against the backdrop of either the dominance or postmodern fading of linear narrative as a mass media form. eurovision instead investigates the productive possibilities for narrative by both interrogating and invigorating it through an interplay with digital aesthetics. The outcome is a new and exhilarating direction for spatial and temporal montage that no longer sees digital artefacts as mere simulators of film, the photographic image or other analogue media, but ushers in the possibility of what new media critic Lev Manovich has termed “digital cinema” (L. Manovich, The Language of New Media, MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass., 2001).

Where earlier computational experiments with narrativity, such as Peter Greenaway’s high definition video Prospero’s Books, failed to sustain narrative within the cumulative fragmentation of digital, visual layering, Wallace’s piece develops a kind of modular narrative that holds in place the splitting of the screen’s frame. eurovision is structured around 4 segments of songs sung by the Russian, Swedish, French and German entrants to the Eurovision Song Contest in 2000; each country’s contestant activating a different screen template for viewing a set of cinematic and photographic juxtaposed and sequential cut-ups comprising that sections’ module. Like a graphic mask that sits over the viewing plane, the screen is divided by blackness into smaller square and rectangular spaces that over time exchange their shape and scale and through which video and images stream at the viewer. Wallace was initially interested in imagining the piece for internet broadband delivery in which multiple streams of information could be delivered on the fly from a database of media stored on a server. (See Wallace’s artist’s statement: www.machinehunger.com.au/eurovision/statement.html.) But rather than some techno-utopian hankering after the promise of bigger and better, eurovision’s resulting linear meditation on the much proffered potentialities of speedier digital media gives viewers temporal distance from a world in which information incessantly streams at them.

The strategy of eurovision is not to substitute misinformation and chaos as a negative critique of the over-saturated and speed-obsessed arena of contemporary, global media consumption. Instead its formal experiments with the screen as a panel, almost an interface, distributes and resequences the internal coherence that the homogenisation of entities such as ‘the information age,’ cinematic narrative and European culture are presumed to possess. The vision of Europe we encounter in the video becomes increasingly situated historically and socially rather than remaining a singular, mythical entity suggested by a myopic European ‘vision.’ While the kitsch veneer of the performers and the consistently blithe pop melodies of the Eurovision song contest suggest a formula for a multicultural Europe, the filmic content playing through eurovision’s multiple screen frames, composed of cut-ups of Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal (1957) and Jean-Luc Godard’s Two or Three Things I Know About Her (1967), offers us a darker sense of a more alienated and displaced Europe.

For an Australian audience the video straddles tensions between representations of European-ness: the Eurovision songs, perhaps a reminder of languages left behind in the process of migration or—to Anglo-Saxon Australians—sounds and cultures never heard; the subtitles of the French films—glimpses of an intellectual and arthouse cinema scene; the 1950s and 60s Russian space program footage in the smaller side frames challenging our familiarity with the US version. If the technical effect of multiplying and dividing the screen space displaces a unified viewing perspective, then so too do the disjunctive images of Europe offset any attempt we might make at constructing this culture as easily digestible and assimilable. Yet the remarkable achievement of eurovision is its sheer watchability. It elegantly realises just the right blend of fragmentation and repetition. The re-use of older media form and content has been a common feature of digital art and of digital media within advertising and popular culture. And yet this can lead to a kind of visual malaise in which the content of a piece is evacuated or else the audience’s affective response is caught up in admiring technical mimicry. Instead the cinema and television cut-ups in eurovision conjure memories of a nascent post-war European culture grasping at the beginnings of global and mass media culture; a culture out of which contemporary information cultures are born. The subtitles from Godard’s film replayed and multiplied across the screen and tempo of the video, speaking to us from the 1960s of the failure of communication are just as relevant for the state of global communications networks today.

The repetition and fragmentation of form and media in eurovision successfully holds the eye because it is not used as simple commentary on the repetitiveness or loss of meaning produced by digital culture. Instead the selection and replaying of only segments from the films or television footage indicate that the digital reiteration of other media can provide new ways of understanding forms such as narrative. Linda Wallace redeploys only subplots from the Bergman film revolving around the characters of the knave and the witch that deal with the way social groups produce outsiders. This focus on the space of the outside is taken up at a formal level by the video’s digital aesthetics, which investigate the production of narrative outside of a centralised coherence or structure. Against the expectation of a linear unfolding of plot driven by a single event or character, eurovision suggests narrative can be produced through techniques of recombination, moving the subplots or modules around, pulling them apart and fitting them back together again. Narrative can then be seen to rest not upon linearity and singular viewpoint but on the layering, combination and texturing that differently sequenced modules bring to events. It is here that works like eurovision offer us new and productive possibilities for digital video as it thoughtfully remediates the content, form and history of painting, graphics, photography, film and television.

Eurovision, video, Linda Wallace, 2001. www.machinehunger.com.au/eurovision/

RealTime issue #53 Feb-March 2003 pg. 22

© Anna Munster; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Blast Theory, Desert Rain

“data [information] terra [earth] investigates not only the technological, but emotional, psychological and spiritual implications of the digital paradigm, and…delves into the advent and purposing of data mapping.”

dLux media arts flyer, November 2002

Birds are filling the skies again

Feather numbers are up and up. Graph spikes in what the birdologists refer to as ‘incidents.’ Witness the parklife across from Sydney’s Central Station. Abundance of beak and claw, a near liquid blob of feathery life force gathered, feeding ravenously. Can’t even see the footpath. People watch nervously from a distance, awed by the spectacle, daring not to think what such a mass might be capable of. Whispers travel around the perimeter—a boy in there somewhere, 8 years old.

dLux blurbalish

futureScreen02 data*terra was the 5th annual dLux X=ploration of new media meets cultural theory and emerging sci-tech. “Investigating the mediation of data across technological, cultural and physical terrains,” the event boiled down to: Data Conspiracy, a live debate over dinner (no spectators); The All Star Data Mappers, a survey and exhibition of database voyeurs and network fetishists curated by John Tonkin; Terra Texts, commissioned essays by Sean Cubitt, Dr Ann Finnegan, Bill Hutchison and Mathew Warren (www.dlux.org.au); Interalia, live thematic audiovisual assaults at The Chocolate Factory, Surry Hills; and Desert Rain, a large scale installation by Blast Theory (UK) at Artspace.

The man on TV

He said there was a major earthquake in Tokyo, Japan. SBS coincidentally, had programmed for that night’s viewers a cautionary tale about the inevitability of The Big One that’d shake Tokyo far beyond its state-of-the-art emergency services. And so it was with added resonance that the fragile, interconnected nature of our global economic electronic was emphasised one sober late 90s evening. Sever the Tokyo tendrils and the world wakes to a depression.

Joining the dots

The All Star Data Mappers mostly consists of websites clickable from the dLux homepage, so visualisation and data mapping enthusiasts can explore this fine selection of provocative datamapping tools months after the exhibition’s end. For me the Oz-gong went to the Firmament software interface for a radio telescope by Mr Snow and Zina Kaye. Josh On’s now infamous TheyRule.net slices through the Fortune 100 company connections with an incredible visual succinctness and Minitasking.com highlights the distributed backbone of the popular peer to peer Gnutella filesharing network.

Virtual warfare

As a large scale and much hyped Virtual Reality environment and interactive art installation, I expected to engage with Desert Rain at Artspace as a boy. Not that I’d be grinning because I was getting free trigger finger in textured corridor practice, just that I expected more technology than necessary. Somewhere amidst the gee-whizardy, the novelty, the gimmickry, the sheer cost of it all, I expected I’d feel like the kid who notices that the emperor isn’t in fact wearing any clothes. Once the impressive infrastructural veneer was peeled away, would it reveal a lack of substance at the installation’s core?

Real warfare

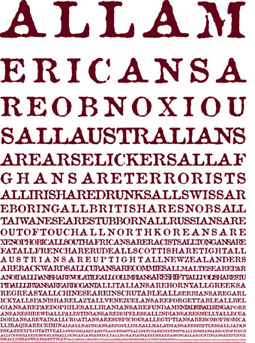

“If they do it, it’s terrorism, if we do it, it’s fighting for freedom”, said the US Ambassador in Central America in the 1980s when asked to explain how US actions like the mining of Nicaragua’s harbours and bombing of airports differed from the acts of terrorism around the world that the US condemned. Since World War II, the US has dropped bombs on 23 countries including: Korea 1950-53, China 1950-53, Indonesia 1958, Cuba 1959-60, The Congo 1964, Laos 1964-73, Vietnam 1961-73, Cambodia 1969-70, Guatemala 1967-69, Grenada 1983, Lebanon 1984, Libya 1986, El Salvador 1980s, Nicaragua 1980s, Panama 1989, Iraq 1991-1999, Sudan 1998, Afghanistan 1998, and Yugoslavia 1999.

Veneer peeling

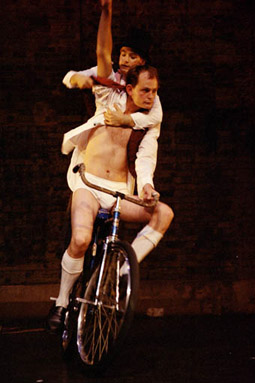

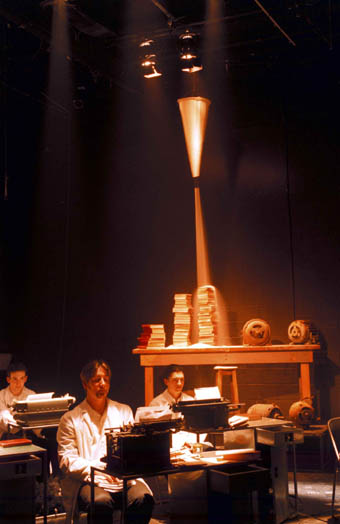

Artspace. Spanky, Nick Eye-fi, The Lalila Duo and a little boy. All of us in the raincoats provided. In separate fabric cubicles, wearing microphone headsets and staring at screens formed by water dripping from the ceiling in front of us. Projectors glare onto the other side of the water, providing an almost blurry, ghost-like image to navigate. Finding our way around is done by leaning left, right, forwards or backwards on the small platform beneath our feet and by talking to each other through our headsets when we come within range in the 3D space we’re watching. With the sound of the constantly raining screens, each other’s muffled headset banter and the polygon war playground shining in the glimmery mist, it’s hard for a boy not to be impressed. We each have 30 minutes to find our target characters and collectively get our butts to a particular exit. But what does it all mean?

Oil-soaked birds

“…real events lose their identity…when they become encrusted with the information which represents them…As consumers of mass media, we never experience the bare material event, but only the informational coating which renders it ‘sticky and unintelligible’ like the oil soaked bird.” (Paul Patton tackles Baudrillard on the Desert Rain flyer.)

Desert guts

So I’m in this 3D Pac-man game and I’ve found my sticky ‘target.’ Eerily silhouetted in front of the projector, a character approaches the water screen from behind, then walks straight through it and gives me information about my target. Actors as soldiers have instructed us on our mission, guiding us to the cubicle and over a large quantity of sand to a mock-motel room, where our team learnt via video-recorded interviews that each ‘target’ had experienced the Gulf War in an unorthodox manner. This physical integration of people into its virtual environment and the evocative aesthetics of the physical space distinguish Desert Rain from most war-based computer games. This is just as well because Desert Rain’s simplicity means it couldn’t compete as gameplay alone.

Breadcrumbs

Ritual and sacrifice are understandable responses to larger forces we don’t understand. Daily breadcrumb dumpings were now occurring to appease the flocks. Thing was, a kid had been trapped under one dumping and, when the birds fluttered away, he was no longer there, just a distraught mother hopelessly scanning the empty footpath for some trace. As she looked up, about to cry to the heavens, she fell to her knees rubbing her eyes—the birds were flying in formation in the shape of her boy.

Motion Blur 75%

Blast Theory’s goal is to blur the boundaries between real and virtual events, “especially with regard to the portrayal of warfare on television news, in Hollywood films and in computer games.” This ‘mixed reality’ approach succeeds in part, hampered by the extent to which you are shepherded through the process and your lack of capacity to do anything meaningful in the installation—explore a maze representing a Gulf War bunker, find character and find exit. The Gulf was a resonant and important theme, but I didn’t really gain any new insights into its real or virtual nature through the game options I explored that couldn’t have been expressed through a simple website or pamphlet. Nonetheless it was a highly engaging experience, and Blast Theory’s next work on the streets and online using satellite tracking and handheld technologies should build on this and possibly appear in futurescreen:03.

futureScreen02 data*terra, www.dlux.org.au/dataterra, Nov 15-Dec 7. Desert Rain, Blast Theory, Artspace, Sydney Nov 16-22, 2002. www.blasttheory.co.uk

RealTime issue #53 Feb-March 2003 pg. 23

© Jean Poole; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Kaoru Motomiya, California lemon sings a song

photo Megan Jones

Kaoru Motomiya, California lemon sings a song

What would you expect of an International Symposium on Electronic Art? It suggests Peter Stuyvesant—yout international passport to new media pleasure—sweeping views, gold jewellery and sophisticated fashion. A symposium is a formal intellectual presentation and/or a drinking party in the classical Greek style. Electronic art sounds a bit, well, nerdish, leaving you with…a Microsoft conference in an interactive chateau in Aspen?

ISEA 2002 was held in Nagoya, a regional centre 2 hours south of Tokyo. The official theme, Orai, loosely means traffic—comings and goings, contract and communication—and participants were encouraged to respond to this. The symposium’s program, which included exhibitions, academic presentations and performances, was located around a small harbour. Once the official port, it has been re-zoned as a public space, including an aquarium, small museums and a park. About 100 academic presentations were given across 4 days, and 57 installations were housed in 2 huge, disused shipping warehouses.

Kaoru Motomiya’s California lemon sings a song was a highlight of the exhibition. Lemons joined by wires to digital chips produced simple melodies generated by electrical currents from the fruit acid. The audience must kneel, remove the lids from coin-sized boxes on the floor and put their ears almost to the ground to hear the work. First installed at the Headland Arts Centre, California, the piece was made in the shape of a missile, at 1:1 scale, using the same number of lemons as people and dogs who worked in an adjoining former missile base. The missile was pointed at Japan, where the lemons were to be exported. In Japan this work built upon the strong atmosphere of the abandoned warehouses in which the exhibition was held.

Another highlight was Date and Time, a retrospective of Californian video artist Jim Campbell held in the Nagoya City Art Museum. Campbell’s work uses monitor-sized fields of LEDs, rather than monitors or projection, as the display stage of his video pieces. While this technique recalls pointillism, the grid is coarser, heightening the level of abstraction. In pieces such as Running, Falling the movement of a human within the frame becomes intriguingly ape-like, recalling the ambiguous humanity of the opening scenes of 2001: A Space Odyssey.

The performance program favoured live sound/video presentations in the currently popular synchronised eye-candy style. Standing out from the crowd was Faustentechnology, a live audio/visual performance by Quebec duo Alain Thibault and Jan Breuleux. Their tight, minimal beat composition and video footage of abstracted land and cityscapes allowed for dynamic connections between the sounds and images, building on filmmaking techniques. Akiyo Tsubakihara and Yosuke Kawamura’s performance Ambiguous Senses/Misleading Feelings 2, also built upon established techniques, exploring video projection’s possibilities as a spotlight, highlighting small cropped squares of light on the dancer’s body.

Within the academic program, Alex Baghat’s presentation of the public-space noise works of Ultra-Red and Infernal Noise Brigade was engaging and well supported by documentary examples of the artwork. Shawn Decker’s brief talk illuminated his innovative sound installation practice, which employs low tech means in effective ways—using small motor and microprocessor units to trigger sound sculptures that display evolving group behaviours, and various resonators—such as metal buckets—acting as speakers. Decker’s work was inaudible amongst the soupy noise inside the exhibition space. Similarly compromised was Melinda Rackham’s engaging virtual space Empyrean and UK work, 32 000 Points of Light, a sound/video projection by Andy Gracie, Alex Bradley, Duncan Speakman, Matt Mawford and Jessica Marlow. The careful composition and otherwise seductive qualities of these soundtracks were also lost in the noisy setting.

Further serious problems existed—both with the local co-ordinating organisation, Media-Select, and the parent group who oversee the ongoing activities. ISEA is curated by committee, arguably allowing greater diversity and more artists who are less well-known into the program. This approach favours larger scale presentation, as a greater number of interests are represented. However, while a theme usually brings focus, in Nagoya the program was mediocre and half-baked. All the work in the exhibition suffered from overcrowding and most artists were disappointed by the result. By contrast the organisational style of the Multimedia Arts Asia Pacific (MAAP) resulted in a focused and dynamic event. Held recently in Beijing and curated by Kim Machan, MAAP was streets ahead of ISEA in its high standard of presentation, diverse works, artistic and intellectual rigour (see report in RT 54, April-May). Further, all the works in MAAP were operational and ready for public presentation, which could not be said of someworks in ISEA.

The massive number of installations, performances and presentations is an ongoing issue for ISEA and feedback from those who have experienced prior festivals indicates similar problems. Despite a huge production staff of committee members and volunteers there is simply too much, spread over too many venues. ISEA, contrary to its image, is poorly resourced—most artists sourced presentation costs independently. The million dollars necessary to properly mount ISEA’s ambitious program is not there.

More problematic, however, is ISEA’s context. Its original purpose to create international connections for artists in the emerging field of Electronic Art no longer seems relevant 14 years later. Roy Ascott, head of the CAII-Star post-doctoral research organization in the UK, suggested a name change from Electronic to Emergent Art, questioning the absence of work from bio-art, molecular and nano-technology, genetics, consciousness research and paranormal perception.

ISEA needs to shape up or ship out…but whaddya know—their next show is on a very big BOAT!—in the Baltic Sea, with the sharper figure of ex-ANAT Director Amanda McDonald Crowley at the helm as Executive Producer. Its organisational mechanism is already well underway.

ISEA 2002, 11th International Symposium on Electronic Art, Nagoya, Japan, Oct 27-31, 2002.

RealTime issue #53 Feb-March 2003 pg. 24

© Bruce Mowson; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

'There was always more in the world than men could see. The precious things are thought and sight, not pace. It does a bullet no good to go fast, and a man…no harm to go slow, for his glory is not at all in going, but in being.'

John Ruskin, The Art of Travel

140 years ago, when one could see Europe by train in a week, John Ruskin was distressed by the speed at which we viewed the world, overlooking simplicity, subtlety and detail. These days, when the Inter-Society for the Electronic Arts (ISEA) community jets into a global locale to hold their weeklong biannual exhibition and symposium, the desire to go slow is again relevant.

In one of ISEA’s opening dialogues, Japanese media theorist Hiroshi Yoshioka echoed this sentiment emphasising the need for slowness, subtlety, and contemplation when viewing electronic arts. This seemed strange from my gaijin perspective of Japan’s furiously paced technological evolution—its constant production of smaller, faster, cuter things. But there is a new social and cultural movement emerging in Japan, promoting an environmentally friendly, symbiotic lifestyle and discouraging mass consumption and waste. It’s not quite the slacker generation, but organisations like Sloth Club (Namakemono), whose motto is Slow is Beautiful, are embracing slow food and helpful technology. With this cultural insight framing my mood, I sought out the mediated aesthetic of being.

Japanese artist Kaoru Motomiya’s elegant interactive sound installation, California lemon sings a song, a rocket shaped floor installation of Sunkist lemons and traditional Japanese cooking pots connected by copper wire, generates its own electricity, becoming a fruit acid battery. Viewers can smell fresh citrus and hear sounds of greeting card size musical devices when they open the pots. Motomiya says that when she considers electronic arts, she thinks about power generation, not only consumption. The lemons also provoke us to contemplate globalisation, as we fuel our bodies, our own electronic circulatory system, with produce exported from around the world. Nature and technology entwine.

Unfortunately, delicate work like this suffered in the Pier Warehouse Exhibition, where disparate installations were squashed together. The lack of discrete viewing and listening spaces was consistently a problem for my gallery-trained sensibilities. The subtly shifting soundscapes produced by navigating through Squidsoup’s (UK) Altzero multi-user-networked shockwave installation were swamped by surrounding works, as was US-based Beatriz Da Costa’s Cello. This normally well disciplined robotic cello player, which alters its movement and sound according to viewer feedback, reacted erratically to the almost market place cacophony and kept tuning the cello rather than playing through its repertoire.

Faring better, as it relied on touch sensors rather than sound, was Talking Tree, which postulates a posthuman relationship with nature, as Takeshi Inomata and Tsutomu Yamamoto (Japan) search for the intrinsic information on being via a piece of driftwood. Touching the exposed and vulnerable rings of the magnificent sawn-through Kiso River tree stump activates texts on the effects of the unmitigated destruction of the forests and images of the stump’s mountain origin, as a ghostly 20 metre animated tree shadow eerily sways to the sound of axes chopping into the trunk.

Our embodied relationship with technology was a recurring theme in the ISEA Symposium. Academic papers competed for listeners’ attention with the venue’s superb gold and silver flock wallpaper, mirrored ceilings, and intricate sculptural chandeliers. Slovenian artists Darij Kreuth and Davide Grassi spoke of incorporeal communication in networked virtual reality performance. In their production Brainscore, sensors are attached to the head of the performers who remain physically constrained, while their tracked eye movements and electrical pulses from brain waves control their avatars. The vaguely face-shaped avatars consume data from the internet resulting in slow changes to their form, colour, size and location. The changes in turn effect the eye movements and brain functions of the performers, providing a self-sustaining feedback loop between performers and software and generating a projected 3-dimensional choreography of colour, shape and sound for the audience. Boundaries of human and machine consciousness subtly merge.

Another unexpected delight was Jim Campbell’s (US) work, at an associated exhibition in Nagoya City Art Museum. Campbell’s unique style questions the subjective experience of technology. He creates a matrix of varying dimensions, for example 32×24 (768) pixels, out of LEDs on which simple black and white (or red) video images of a person walking across the screen are reproduced. The LED display transforms the visual information into a numerical code resulting in a hauntingly beautiful and simple mediation of analogue metamorphosed into digital. In other works he includes a sheet of diffusing plexiglass in front of the grid to produce a blurring effect, shifting the digital pixel image back to a continuous analogue film image. Simplicity is powerful.

So too in the Electronic Theatre with Patrick Lichty’s fabulous 8 bits or less, a short film on alien abduction. Shot on a Casio WristCam with music produced on Commodore 64, the work proved that lo-tech is every bit as compelling as high fidelity: intricately rendered realism. Slowness and subtlety were also the strength of Anne-Sarah Le Meur’s (France) animation Where It Wants To Appear/Suffer. Simple surfaces meet with slow movement; smooth or fibrous textures, subtle colour and minimal light give the impression of both microcosm and macrocosm. Animal, vegetable and mineral are condensed in underwater or intra-body environments.

Appear/Suffer is the first stage of a virtual environment project, Into the Hollow Of Darkness, based on the viewer’s desire to perceive, about which Le Meur spoke at the symposium. In large-scale projection she intends abstract visual sensation to produce a strange intimacy with the image. Nothing tangible is represented—everything rests upon the power of the images and the reciprocity of the power the viewer has over the images. Abstract representations move away from the viewers as they move towards them; the viewers gradually learn that by becoming passive, motionless, they can pause the forms, or “tame” them as Le Meur suggests. This slow dance of viewing the artwork gives the impression the forms are alive, even looking back at you. Slowness creates intimacy.

My meander through the exhibitions and conference presentations was refreshing, revealing works that seek to seduce rather than control the viewer, immersive and interactive on subtle levels, based on simple principles often backed by complex technology. ISEA aroused my desire for feeling, listening and slowness to provide a delightful respite from knowledge, action and speed. It’s nice to be reminded that contemplation is as valuable as manipulation.

ISEA, Inter-Society for the Electronic Arts biannual exhibition and symposium, Nagoya, Japan, Oct 27-31.

RealTime issue #53 Feb-March 2003 pg. 24-25

© Melinda Rackham; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

catchafallingknife.com

photo Michael Goldberg

catchafallingknife.com

We are yet to see what capital can become. So goes the ‘new economy’ mantra as its proponents lay claim to the future, which is synonymous with the ‘free market.’ Mastery of the latter supposedly determines the former. Bubble economies—exemplified most spectacularly with dotcom mania and the tech wreck in April 2000, which saw the crash of the NASDAQ—are perhaps one index of the future-present where the accumulation of profit precedes by capturing what is otherwise a continuous flow of information. Information flows are shaped by myriad forces that in themselves are immaterial and invisible, as they do not register in the flow of information itself. The condition of motion nevertheless indelibly inscribes information with a speculative potential, enabling it to be momentarily captured in the form of trading indices.

Michael Goldberg’s recent installation at Sydney’s Artspace—catchafallingknife.com—combines software interfaces peculiar to the information exchanges of day traders gathered around electronic cash flows afforded by the buying and selling of shares in Murdoch’s News Corporation. With $50,000 backing from an anonymous consortium of stock market speculators cobbled together from an online discussion list of day traders, Goldberg bought and sold News Corp shares during 3 weeks in October-November last year (for background to the installation see RT51).

Information flows are at once inside and outside the logic of commodification. The software design of market charts constitutes an interface between informational nodes and flows. The interface captures and contains—and indeed makes intelligible—what are otherwise quite out of control finance flows. But not totally out of control: finance flows, when understood as a self-organised system, occupy a tense space between absolute stability and total randomness. Too much emphasis upon either condition leaves the actor-network system open to collapse. Evolution or multiplication of the system depends on a constant movement or feedback loops between actors and networks, nodes and flows.

catchafallingknife.com

photo Michael Goldberg

catchafallingknife.com

Referring to the early work of political installation artist Hans Haacke, Goldberg explains this process in terms of a “real time system”: “the artwork comprises a number of components and active agents combining to form a volatile yet stable system. Well, that may also serve as a concise description of the stock market…Whether or not the company’s books are in the black or in the red is of no concern—the trader plays a stock as it works its way up to its highs and plays it as the lows are plumbed as well. All that’s important is liquidity and movement. ‘Chance’ and ‘probability’ become the real adversaries and allies.” (Interview with Geert Lovink, www.catchafallingknife.com)

Trading or charting software can be understood as stabilising technical actors that gather information flows, codifying these in the form of “moving average histograms, stochastics, and momentum and volatility markers” (Goldberg). Such market indicators are then rearticulated or translated in the form of online chatrooms, financial news media and mobile phone links to stockbrokers, eventually culminating in the trade. In capturing and modelling finance flows, trading software expresses various regimes of quantification that enable a value-adding process through the exchange of information within the immediacy of an interactive real time system. Such a process is distinct from “ideal time,” in which “the aesthetic contemplation of beauty occurs in theoretical isolation from the temporal contingencies of value” (Ed Shanken, “Art in the Information Age”, www.duke.edu/~giftwrap/ InfoAge.html).

An affective dimension of aesthetics is registered in the excitement and rush of the trade; biochemical sensations in the body modulate the flow of information, and are expressed in the form of a trade. As Goldberg puts it in a report to the consortium halfway through the project after a series of poor trades based on a combination of ‘technical’ and ‘fundamental’ analysis: “It’s becoming clearer to me that in trading this stock one often has to defy logic and instead give in, coining a well-worn phrase, to irrational exuberance.” Here, the indeterminacy of affect subsists within the realm of the processual, where a continuum of relations defines the event of the trade. Yet paradoxically, such an affective dimension is coupled with an intensity of presence where each moment counts; the art of day trading is an economy of precision within a partially enclosed universe.

However, the borders of a processual system are also open to the needs and interests of external institutional realities. The node of the gallery presents what is otherwise a routine operation of a day trader as a minor event, one that registers the growing similarities between art and commerce. Interestingly, the event-space of the gallery expresses the regularity of day trading with a difference that submits to the spatio-temporal dependency news media has on the categories of ‘news worthiness.’

A finance reporter for Murdoch’s The Australian newspaper reports on Goldberg’s installation. Despite the press package, which details otherwise, the journalist attempts to associate Goldberg’s trading capital with an Australia Council grant (which financed the installation costs) as further evidence of the moral and political corruption among the ‘chattering classes.’ In this instance of populist rhetoric, the distinction between quality and tabloid newspapers is brought into question. The self-referentiality that defines organisation and production within the mediasphere prompts a journalist from Murdoch’s local Sydney tabloid, the Daily Telegraph, to submit copy on the event. Unlike the dismissive account in The Australian and the general absence of attention to the project by arts commentators, Goldberg notes how the Daily Telegraph report made front page of the Business section (rather than the News or Entertainment pages), in full colour, with his picture beside the banner headline “Profit rise lifts News.” The headline for Goldberg’s installation was smaller: “Murdoch media the latest canvas for artist trader.”

Here, the system of relations between art and commerce also indicates the importance that storytelling has in an age of information economies. Whether the price of stocks goes up or down, profit value is not shaped by the kind of political critique art might offer, but rather by the kind of spin a particular stock can generate. Goldberg’s installation discloses various operations peculiar to the aesthetics of day trading, clearly establishing a link between narrative, economy, time and risk, performance or routine practice and the mediating role of design and software aesthetics. catchafallingknife.com demonstrates that it is the latter—a theory of software—that still requires much critical attention. And unlike most players in the new economy, Goldberg’s installation was a model of accountability and transparency.

catchafallingknife.com, Michael Goldberg, Artspace, Sydney, Oct 17-Nov 19, 2002. www.catchafallingknife.com

RealTime issue #53 Feb-March 2003 pg. 25

© Ned Rossiter; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

scanner

Of all the arts-centres-on-riverbanks in Australia, Brisbane’s Southbank is one of the most distinctive with its string of performing arts venues, a museum, a major gallery, shops, restaurants, a rainforest garden, cafes, a very popular pool and artificial beach, university faculties (including music and visual arts) and, just a block back, a stylish shopping and eating strip replete with IMAX cinema. There’s also the nearby entertainment centre and exhibition halls. And there’s still room for more growth, which will include the new contemporary art home of the Queensland Art Gallery.

Millions of people go to Southbank every year, just passing through, promenading, having an after work drink, on their way for a swim or to see a show or enjoy a street market. This is a great potential audience for the very latest in public art, something that in Australia has been pretty much limited in the public imagination to sculptures, and a fair few controversies among them. Southbank Corporation, which manages the area, has appointed Zane Trow, formerly Artistic Director of The Brisbane Powerhouse Centre for Live Art, as its Director of Public Art. Selected by and working to a brief from the Public Art Advisory Committee (visual artist Jay Younger, Queensland College of the Arts, art theorist Rex Butler, University of Queensland, both from Brisbane, and Melbourne architectural reviewer and design consultant Joe Rollo), Trow has embraced this unique opportunity with his customary passion, planning a 3 year program, the first stage of which will be launched in April this year.

Trow explains, “South Bank Corporation Public Art Committee has developed a policy and I’m the implementation. It will be a mixture of research into permanent works and a time-based temporary installations program, a lot of which is focused around the Suncorp large screen. This is work that will be in the public domain. It’ll be free, sophisticated work with high level production values. There will be 2 or 3 temporary installations a year involving sound and image with performance and durational components for some of the time.”

Trow declares that there are already very good local new media artists working in the direction he wants to go and with whom he is eager to work—artists like Keith Armstrong and Lisa O’Neill of the transmute collective, Igneous (James Cunningham and Suzon Fuks) and Di Ball, as well as international artists he’d like to have working on Southbank. For local artists, says Trow, “it will certainly give them the opportunity to work on a large scale.”

Although he won’t launch his program until April, Trow offers a taste of things to come: he’s bringing UK DJ and sound artist Scanner back to Brisbane, this time to present his large screen performance-remix of the soundtrack of Jean-Luc Godard’s Alphaville with his own score, to be presented late night, outdoors. The event will be accompanied by a impromptu sound/image performance from local artist Lawrence English, I/O 3 and improviser Mike Cooper.

Trow also offers an example of a major work he is pursuing with Elision, Australia’s premier new music ensemble, and, potentially, UK composer Richard Barrett (who collaborated on the company’s Dark Matter in 2001) and leading Australian new media artist, Justine Cooper.

“Allowing key artists to come together to work on a large scale and allowing them access to a large screen and a performative environment,” says Trow, “is unusual in Australia. While there are large screens in this country, a lot of them are tied to special projects for festivals, or for open air film programs, or occasionally in museums. There’ll be one in Melbourne’s Federation Square, which I’m sure ACMI (Australian Centre for the Moving Image) will put to good use…but it’s rare to allow artists really playing with performance installations to get their hands on a resource like that. It’s in situ, a very good one, it’s digital—so it can take a line straight out of a laptop or a DVD player—and it’s mobile. There are about 4 locations for it I’ve identified so far, including floating the screen on the river on a barge for a river-based installation. Having it as an asset is fantastic because you don’t have to go to a ridiculously expensive commercial hire company and ask how much it’s going to cost a day. You’ve actually got the thing and a team of people here who know how to use it.”

Trow’s 3 year program includes works he’ll be commissioning, “a couple in partnership with existing events and linking to the Millennium Arts Project.

“That project is a major capital investment by the state into a renovation of the Queensland Museum and the State Library and the development of the contemporary gallery of the Queensland Art Gallery. That gallery will open in 2005 and will be a great opportunity to work within the precinct on ideas of contemporary culture and public space. It all seems to me to be very pertinent to think about the relationship of the public domain with the Feds circling around the idea of charging for admission to gallery spaces…Clearly the philosophy here at Southbank is about protecting the public domain, having a space in the city that is purely about relaxation and recreation, and creating art happenings in it for the interest and amusement of the general public.”

Trow is pleased to be working with a committee that is “thinking away from the idea that art is good for you or educational…We seek to place contemporary and broadly radical art in public space. It might even be easier putting such innovative work in the public domain, rather than sticking it indoors in arts centres and charging. It’s an opportunity to practically engage with ideas of contemporary art and popular culture. That’s what excited me, the prospect of being able to reach out into those areas with artists playing with communications and ideas.”

There are other aspects to Trow’s vision: he wants to encourage sound artists in particular, especially given there’s a new sound system going into Southbank soon. As well, he’s eagerly developing partnerships with festivals (like the Queensland Biennial Festival of Music). The Public Art program will also represent the Corporation in connection with the Percent for Art scheme, which requires developers to allocate funds for artwork on their sites, and the Melbourne Street development which Beth Jackson, formerly of Griffith Artworks, is working on for Southbank, planning permanent artworks.

Trow is looking forward to “twisting up the whole idea of public art” and getting past the inhibiting bureaucratic vision of it that Rex Butler has critiqued so well. “There’s no assumption in our policy,” says Trow, “that Southbank should behave like anyone else…It’s not an arts organisation. It’s a state corporation set up to manage a public space and the thinking here is about public culture and how you can change with the times, dealing with public art, with the business community, with tertiary educational developments…the mix of people is unique. There is a lot of good thinking about activating the river and integrating the entire precinct.”

RealTime issue #53 Feb-March 2003 pg. 26

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Jay Younger, Untitled 1

Glare is a term that has contradictory or polar meanings. Used as a verb, ‘to glare’ is to fix with a fierce or piercing stare. As a noun, the word takes on different connotations. The glare is a strong dazzling light, an oppressive light that shines with tawdry brilliance. In the former sense, the glare fixes; in the latter it undoes fixity and creates dispersion. Jay Younger’s survey exhibition, Glare, at the University of Queensland’s Art Museum, plays with these contradictions. The tension between the expressed ideological intentions of the artist and the work’s blinding exuberance makes this exhibition rewarding and fascinating.

Glare is not a retrospective, but provides the opportunity to view and review the artistic output of one of Queensland’s most significant contemporary artists. Younger has played a formidable role in the development of contemporary art in Brisbane over the past 2 decades, not just as an artist, but also an educator, curator and mover and shaker in the arts. The social and political consciousness that has enabled her to contribute so profoundly to the development of contemporary art in Queensland also provides the central impetus for her artwork.

This impetus is most apparent in Younger’s installation works of the early 90’s. For Glare, she recreated the grotesque installation work Gormandizer (1993). In a critique of the inflexible concrete structures of masculinist culture, the artist coated a cement mixer in pink sugar. In her hands, this object becomes a great gustatory machine, chewing and dribbling forth a rich mucous of glucose and faux jewels. Other significant installations from that period, Big Wig and Charger (1995) and Trance of the Swanky Lump (1997), are included in the exhibition as video documents.

Big Wig and Charger is the most breathtaking and ambitious of Younger’s installations. It involved 30 women who, in turn, took their place (heads protruding through a hole in the floor of the gallery) beneath an enormous suspended Marie Antoinette wig. While it’s difficult for documentation to capture the immediacy of such an event, Younger’s video creates a powerful narrative that heightens the drama and suspense of the work. In editing the footage, she cuts between scenes of the vulnerable heads of the women, the wig, an idling Valiant Charger in an adjoining car park, and a third space in which headless bodies dangle from scaffolding. Through her focus on the tension of the rope holding the wig aloft, Younger creates a sense of impending doom. In this video documentation and in her re-presentation of Trance of the Swanky Lump, Younger is a consummate storyteller.

Whilst the work in the survey spans the period between 1987 and 2002, it provides the artist with the opportunity to showcase her latest photographic work, the ‘tropical noir’ series Ulterior. Using the glitter and glitz of 70’s kitsch tropicana, Younger has created a pungent tropical noir setting as a backdrop against which to revisit some of the notorious underworld stories and characters of the Fitzgerald era. For Younger, Ulterior aims to break through the illusion that Queensland is a carefree tropical paradise, revealing corruption as a persistent holographic presence.

Stylistically, Ulterior appears to have its genesis in the series of cibachrome photographs, Combust (1991), conceived during an artist-in-residency in the Australia Council’s Verdaccio studio in Italy. In this earlier work, the message is direct and simply composed. In Combust II (1991), a sparkling green pineapple rocket blasts off Las Vegas-style, leaving a trail of pink stardust, whilst in Combust III (1991) the burning letters N O come careening to earth. In the tropical noir photographs, the message is more obtuse with each image highly decorative and crammed full of signifiers. There is a vaguely uneasy feeling of trouble in paradise, but these stirrings don’t seem to unsettle the status quo. It is so easy to get swept up in the decorous glitz and celebration of a place where it is ‘beautiful one day, perfect the next.’ The ‘troubling signifiers’ in the photographs (images of characters from the Fitzgerald Inquiry era) appear as Christmas baubles on an overblown palm tree rather than characters from notorious underworld stories. Perhaps this is Younger’s point, to confront Queensland’s ‘cultural and political amnesia.’ However, the danger is that this meaning does not carry beyond the specific context of post-Fitzgerald Queensland. The works themselves become emblems of decadence and excess rather than a critique of them.

The magnificent full colour monograph that accompanies the exhibition comes complete with commissioned essays by Beth Jackson and Juliana Engberg, and extensive theoretical explanations of the individual works. It establishes the socio-political context for Younger’s work. Here lies the dilemma at the heart of any discussion of this artist’s work. The explanations enable the viewer to trace the political and theoretical impulses underpinning each of the works. Yet the contextual framing provided by the catalogue text tends to be didactic, prescribing in advance how the work is to be read, rather than allowing it to speak on its own playful terms. For example, Big Wig and Charger, Gormandizer and Trance of the Swanky Lump are claimed to offer a feminist critique of masculinist culture. In a similar way, Ulterior critiques what Younger sees as the political amnesia of the post-Fitzgerald era. However, at the level of the material and the visceral, the works move beyond political critique. In this tension I am reminded of Drusilla Modjeska’s claim that “art takes us not into political argument, or not only, but towards the ‘inviolate enigma of otherness in things and in animate presences’” (Modjeska, D, Timepieces, Picador, Sydney, 2002). Jay Younger’s work may be critique, but through it we are moved beyond critique into a realm of visceral corporeal pleasure.

Glare, Jay Younger, installations 1987-2002, Art Museum, University of Queensland, Dec 7-Jan 18, 2002

RealTime issue #53 Feb-March 2003 pg. 27

© Barbara Bolt; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Monika Tichacek, Lineage of the Divine, Cerebellum

photo Liz Ham

Monika Tichacek, Lineage of the Divine, Cerebellum

In her video installation, Lineage of the Divine, Monika Tichacek weaves a complex and visually sumptuous narrative. The protagonist, New York personality Amanda Lepore, is trussed in a salmon-pink, 1950s tailored suit, blonde hair in a net, lips overripe and gleaming, feet squeezed into precarious high heels. The figure paces a room with small, delicate steps, arms crossed, striking a pose in full awareness of being on display. This fetishistic assertion of archetypal femininity raises suspicions about the ‘true’ gender of the figure: is this really a woman or is ‘she’ just acting out? The figure appears to scan the gallery space, which also screams feminine cliché with its walls of studded pink satin, recalling a padded cell as much as the frou-frou bedhead that might grace a girl’s suburban bedroom. The feminine symbolism is interrupted by unmistakably phallic antlers that protrude from the wall, reinforcing the fetishistic yet sexually ambiguous ambience. The antlers, cast in resin in various sizes, evoke a dangerous male sexuality, but also look like children’s sporting trophies.

Close-ups and slow pans fragment and confuse the viewer’s perspective of the figure and the room, although it eventually becomes clear that there are 2 almost indistinguishable personae. The central figure is contemplating another, who lies sleeping, attired in identical clothes and make-up—this is the artist herself. A panning shot reveals that the 2 are conjoined by their hair—a blonde switch that snakes around the room, like an umbilical cord. The first figure slowly comes to touch the other, takes the other’s head in her lap before kneading her face and waking her. All the movements are slow and deliberate, choreographed actions intended for public view not for intimate exchange. Under her pink suit the artist wears flesh-coloured prosthetic casings on her limbs and torso that appear to be attached by strings and hooks to her skin. The first figure pulls these, scratching between flesh and plastic as if to manipulate, or liberate, the other. This scene is underscored by a video image on the facing wall that depicts the artist in prosthetics almost entirely still, breathing shallowly as though in an effort to control pain. She appears compelled to witness the scene opposite, over which she has no control.

Tichacek’s tableau recalls Frida Kahlo’s self-portraits, where the painter often expressed her sexually and culturally conflicted identity through the representation of physical pain, integrating the prosthetics she needed to contain her ravaged body into her compositions. In The Two Fridas, the artist represented herself as 2 women, separate but inseparable, sharing blood and holding hands, but riven by cultural contradictions (one wears indigenous Mexican garb, the other the high-collared lace of Spanish dress). Kahlo exquisitely aestheticised her pain and incapacity, her prosthetics and broken spine are as much a literal depiction of her experience as metaphors for her condition as a Mexican woman of a certain class. This aestheticisation, and extreme feminisation, of prosthetics, pain and incapacity, of dependence and strictured movement, also has a strong presence in Tichacek’s work, as does the metaphor of a divided self. Indeed, the symbolism in Lineage of the Divine crosses well into the bounds of overkill, though it is clear that this excess, this hysterical accumulation of charged signs, is very much the intention of the artist, as she forces us to confront the cultural phenomenon of femininity as well as the process of artistic creation. In seeking to articulate both art and sexual identity, the artist necessarily falls back on the language and gesture of cultural stereotypes. This sense of the need to speak with a borrowed tongue is echoed later in the video’s loose narrative, when the first figure lip syncs and shimmies a la Marilyn Monroe to Secret Love, Doris Day’s hit song that later became emblematic of closet lesbianism. The figure appears fated to perform this ritual of celebrity sexual tease; unable to speak her own language, she is forced to communicate through cliché.

However the overall effect of Tichacek’s installation is neither clichéd, nor a familiar exercise in parody and pastiche. Rather, what the artist has created is a seductively claustrophobic but moving evocation of the self-imposed strictures of identity, particularly but not exclusively, those of femininity and the artist. Like the central character in Bergman’s Persona, Tichacek’s protagonist discovers herself through and exploits her muse, is entirely beholden to and relies on her for her very survival, but rejects her, recovers the power of speech through her muse’s confessions but keeps her most intimate thoughts for others. She is one and the same person, but also entirely estranged from herself. Lineage of the Divine powerfully captures this complicity and estrangement between the authentic self and that reliant on cultural stereotype for realisation.

Lineage of the Divine, Monika Tichacek, part of group exhibition Cerebellum for Sydney Gay Games, curator Gary Carsley, The Performance Space, Sydney, Nov 2002. www.performancespace.com.au

RealTime issue #53 Feb-March 2003 pg. 28

© Jacqueline Millner; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Air Kiss, Steven Carson

photo Lara Thompson

Air Kiss, Steven Carson

Air Kiss’s glowing jumble of deep blue and red light globes dangle in clusters and loop along the walls. Heavy and lovely, lolly-coloured, mouth-shaped, they bloom from the top of columns and drape in strings across the space. Marshalled in corners, each gleaming bulb is linked by a series of wires that spread like secret commands. Yet while they seem to speak of fairs or parties, of Christmas trees and celebrations, beneath their ostensibly cheery appearance courses a vaguely disturbing energy. Contrary to initial impression, the globes are not necessarily celebratory: they could as easily belong to the corpse of a party freshly abandoned as to one waiting to happen.

Traditionally used as decoration, the coloured light globe here is transformed and elevated. As the sole constituent of the work, the globes do not decorate anything—there is nothing to decorate. They enhance nothing, and embellish only empty space. Thus we are welcomed to a floating world of appearances, of deceptive substantiality and ultimately hollow expression. Steven Carson treads a fine line, but successfully. Referring to a world in which style is favoured over substance, he neatly avoids the obvious pitfall of recreating such façadism.

The periodic interruption of the otherwise silent space by an interval of tumultuous music functions to further heighten the viewer’s sense of alienation. All excitement and fanfare, the clamorous crash of bright, harsh, disco-brashness seems to herald some impending event which remains unrealised, its promise unfulfilled. Cut short as unexpectedly as it begins—and before the viewer’s heartbeat has time to calm—this sudden interruption causes the quiet space to reverberate. Its subsequent and abrupt termination results in a resounding disquiet, leaving the space as echoingly hollow as that superficial gesture of affection—as empty as an air kiss.

Such uncertainty enriches Carson’s exploration of the peripheral spaces of mainstream culture and his subsequent manifestation of these metaphorical spaces into literal space. In considering the sub-fields that exist within social life and creative activity, it is to these fringes that both the arts and gay communities—this work was part of the 2002 FEAST Festival—are often relegated. Air Kiss, with its edgy atmosphere of ambiguity, connotes nightclub, brothel and the back alleys of illicit deals and encounters. The sense of seedy glamour—an ambience evoked by its illumination in shades of make-out-room red and druggie-deterrent blue—makes it a place where such ‘alternative’ lives could-can-be lived.

Air Kiss, Steven Carson, Experimental Art Foundation, Adelaide, Nov 21-Dec 20 2002.

RealTime issue #53 Feb-March 2003 pg. 29

© Jena Woodburn; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Joe Berger, still from Covert

Friday nights in February in Canberra, The National Museum of Australia will be the place to be from 7.30pm till midnight as the Museum hosts Sky Lounge, a unique showcase of Australian and international animation, DJs, VJs, electronica, multimedia and graffiti art.

Sky Lounge gives young artists a chance to share their work in a spectacular venue with a national profile and provides young Canberra audiences with greater access to some cutting edge urban culture. It’s also an innovative venture for a museum more usually frequented by an older or family audience. Let’s hope it’s the first of many, with copycats in the form of other nocturnal events in museums and galleries across the country.

Each program combines live performances by some of Australia’s top electronic artists and DJs with animated films on the big and sky screens, projected art, multimedia interactives and graffiti.

Malcolm Turner (Animation Posse) has assembled No future, no past…only present, a collection of 50 animated films from young international filmmakers including work from the Amateur Developers Handbook; Tout Va Tres Bien, a unique take on 3D imaging from France’s Soo-Mi Sung; “cool music, cool tools and cool ideas” in S-Crash by Lindsay Cox and Victor Holder (Australia); Drawing the War, a kerbside view of urban warfare by Lena Merhej (Lebanon); and Pandorama “a camera-less film” by Nina Paley (US).

Visual artist, curator and writer David Sequiera has gathered his Future Projections from well-known as well as emerging multimedia artists. Images by Anne Zahalka, Mark Kimber, John Nicholson, Matthew Higgins, Mike Parr, Anne McDonald, Justin Andrews and David Stephenson will be projected onto the walls of the White Cube in the Garden of Australian Dreams. ANU’s Australian Centre for Arts and Technology is putting together an interactive artwork using multimedia created by students.

You can watch the walls of the White Cube further transformed by some of Canberra’s best graffiti artists (Sinch, Kiosk, Atune) whose work will morph and evolve over the 4 weeks of Sky Lounge. And if you’ve got a minute, you can design futuristic vehicles and buildings and see your creations come to life in a 3D theatre in Futureworld.

Seb Chan from the seminal Sub Bass Snarl curated the Hip Hop program which includes The New Pollutants from Adelaide specialising in “a mish-mash of 8-bit hiphop, beat-driven electronica, funk-laden breaks and dark-themed soundtracks for 80s computer games and film scores” and hiphop with “Australian flava” from Sydney’s The Herd.

Two other Sydney bands put in an appearance: Prop combine minimalism, jazz, funk, trance, dub, techno, classical and groove; Katalyst draw influences from hiphop, funk, soul, soundtracks and jazz. Local hiphop act Koolism is also on the bill along with Toby 1 from Adelaide, self-professed makers of “the laptop rock of the future, creating tracks and processing vocals and instruments in real time.” International guests include DJ Scanner and Tipper (UK) and Andrew Pekler (Germany).

The programs are organised into themes (Retro Future, February 7; Beauty, Feb 14; Hip Hop, Feb 21; and Abstract, Feb 28). The artists are different each night but every program has a mix of live electronic music, film and projection. So choose your vibe or go for the lot. After suffering all that smoke, Canberra deserves a Sky Lounge. RT

Sky Lounge, National Museum of Australia Feb 7, 14, 21 & 28.

RealTime issue #53 Feb-March 2003 pg. 29

© RealTime ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

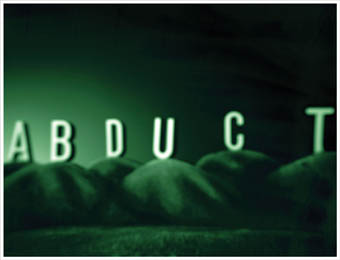

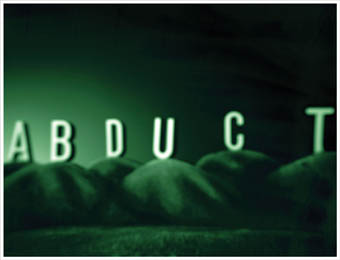

Ronnie Van Hout, Abduct

Narelle Autio’s series of 6 colour photographs, Faith, reveals the dual aspects of her theme—as blind people are led through Sydney streets by their guide dogs, light suddenly illuminates each scene as if uncannily choreographed from above. Autio’s work is part of PhotoTechnica’s She Saw, an exhibition of documentary photography, which contains both recent and older works from well-known and emerging women photographers.

Deep and dark, as if shot at twilight, and full of elongated shadows, the images in Faith contain sharp lines, cones or pinpoints of blazing light, which briefly illuminate the sometimes claustrophobic city settings. These moody cityscapes suggest the shadowed, or completely dark experience of moving through the chaos of the city with no, or limited sight. Some of her subjects, Autio says, can just make out bright casts of sunlight, or feeling the heat of a sudden shaft, will sometimes ask if she took a shot at that moment.

Faith—that the blind invest in the dogs who lead them on their regular routes—is central to these works but so is the examination of public and private space. Guide dogs require a clear box-shape around them to work, which means Autio had to keep well away from her subjects while working, in order not to confuse the dogs who’d grown familiar with her scent. Despite the often crowded settings there is a spaciousness in her composition: footpaths appear like welcome clearings in a crowded grove, train tracks stretch into the distance, suggesting other journeys.

Jackie Ranken photographs places from a great height, and virtually upside down. Ranken’s 8 silver gelatin prints of her home town of Goulburn were made during near-acrobatic manoeuvers in her father’s plane. Prohibited from acrobatic flying above the town, Ranken’s 74 year old dad has perfected the art of tipping his Tiger Moth’s wing to the ground without flipping it so his daughter can capture her evocative shots of the town’s geography. Including both manufactured and natural structures shot from the air, and therefore lacking horizon lines, these Urban Aerial Abstracts take a while to decipher visually. In this sense, like Autio, Ranken prompts us to consider what we take for granted in our ways of seeing, to become aware of how we scan a photograph, assuming we’ll rapidly discover its direct connection to the real.

In Ranken’s work, what looks like a series of boxy houses divided by roads turns out to be a graveyard bisected with paths and then, stepping back, a flag. The circular formations of rose gardens or dams look more like urban forms of crop circle, all their detail miniaturised and made strange; the overlapping roads of the Goulburn bypass become a marvellous spirograph that leads the eye around its curves.

Ranken’s approach lovingly transforms everyday structures into something new. The sweeping lines and textures here remind me of work by some Indigenous artists (Rover Thomas for example) where bold shapes describe features on a 2D landscape. The flatness of Ranken’s style gives the work an appealing abstraction in a show of mostly realist documentary photography.

Moving even further into the stratosphere is Spaced Out at the Australian Centre for Photography. Part of the Sydney Festival, this collection of international and local works examines both real and imagined deep space, space travel and humankind’s continual search for new territory, or life beyond the earth.

In the ACP foyer William Eakin’s series of pigment inkjet prints memorialise the Russian cosmonauts of the early years of space travel. Eakin’s (Canada) series includes space memorabilia—A US Moon Landing Badge and a Japanese collector card featuring cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin. Beside these are several sepia head shots of other Russian cosmonauts; in circular frames they look a little like Russian icon paintings, or faces peering from portholes in antiquated rockets, or from space helmets. These once famous men stare out from black backgrounds pocked with tiny white stars. Eakin’s work reminds us how quickly what was once revolutionary can pass into the frozen zone of kitsch.

Also referencing popular mythologies of space are Ronnie Van Hout’s inket prints in the gallery proper. Each print contains a suitably discomforting concept in the form of white lettering—ABDUCT, UFO, CREATURE, HYBRID—against differing, spookily green landscapes. The word STRANGER appears to melt, morph or pulse before your eyes, and though it’s a trick of the dim gallery light, this animated quality effectively evokes the sci-fi schlock cinema of the 50s which Melbourne-based Van Hout references. While the exhibition notes claim The artist’s work is “less about outer space than the caricaturing and dramatising of cold war insecurities” the oversized white lettering and the hilly backdrops in his MONSTER shot also suggest the mythical land where such films were created, reminding me of the HOLLYWOOD hills where silicon enhancement and Botox are spawning new forms of life but not as we know it.

Juxtaposed against David Malin’s astronomical imaging, South Australian Holly Wilson’s fabricated galaxies and starbursts look remarkably convincing. Reminding us that our fantasies of space are often at least visually linked to reality, Wilson conjures the pocked, rough, corroded surface of a blue planet, the white explosion of a starbirth, by manipulating chemicals on pieces of film.

I find I can only make sense of photographic scientist Malin’s brightly coloured images by imagining them as something closer to home. They make me think of our own deep spaces. A brightly coloured swirling galactic mass looks like something protozoic, something possibly internal; a crimson webby expanse appears more like the surface of the womb shot with a surgical camera than anything out there.

Russian Yuri Batourin turns the camera back to earth from space, revealing the blue curve of our planet, the white-flecked oceans that cover most of its surface. Cited in the notes as a “21st century version of snaps from the plane, the hotel, the conference centre,” Batourin’s work captures the kind of views most of us will never witness. However, a quick search on the Internet reveals that for the wealthy, space travel is now a possibility. For a mere $US20 million (plus 6-months to a year of training, possible nausea while aboard and backaches after landing) you can spend 8-days in the International Space Centre and souvenir your own shot from beyond our universe. Spaced Out makes me wonder how soon it will be before the moon, now colonised, photographed and souvenired; mapped, charted and traversed becomes simply another (expensive) suburb of Earth.

She Saw. Australian Women Documentary Photographers, curated by Karra Rees, Photo Technica, Chippendale, Jan 18-Feb 15

Spaced Out, curators Alasdair Foster & Reuben Keehan, Australian Centre for Photography, Sydney Festival, Paddington, Jan 10-Feb 1

RealTime issue #53 Feb-March 2003 pg. 30

© Mireille Juchau; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Lucas Ilhein

LOCATION: As a co-founder of Squatspace, the artist-run gallery that operated from the Broadway squats in Sydney in the 90s, Lucas Ihlein is a veteran negotiator of the use of public and private spaces. For the duration of their latest exhibition, BILATERAL, Ihlein and collaborator Jane Simon negotiated to live in the Experimental Art Foundation (EAF) gallery in Adelaide. This challenges the dominant mode of exhibitions, where the artist simply installs the work and leaves, rarely taking an interest in its multiple effects and reinforcing the idea of art and the gallery as a kind of placeless, autonomous world. Although the work is a response to Adelaide, it brings other places into tension with the gallery: 3 exhibited works were made on the 1999 Artists Regional Exchange Project (ARX5) in Perth (dream narratives on typewriter rolls), Hong Kong (business cards with gnomic pseudo-proverbs in English, German and Cantonese) and Singapore (copies of a small booklet, My Typewriter Only Speaks English, featuring found and original images and texts).

MATERIAL: BILATERAL makes use of old and new writing/inscription technologies: nostalgic and playful, slow before fast, paying attention to everyday, seemingly inconsequential remainders. Rubber stamps, silk screen prints, stencilled letters and Letraset reference 60s and 70s network art practices, while contemporary technologies are used in refreshing, ordinary ways. A VCR suspended in a net throws an oblique projection of an aeroplane flight path over Sydney across 2 walls and above a bed. SMS messages form the basis of textpadpomes, for example, CAN’T READ/SCREEN CRACKED and POLAROID HAS GONE BUST SO STOCK UP ON FILM CAUSE THEY WON’T MAKE IT ANYMORE. As postcards these sell for $1 each—here in Adelaide there aren’t too many buyers. The touch-ability of the work and its invitation to participate is unusual and meets with resistance as well as engagement. A couple of people I ask think the sign “please buy” doesn’t mean what it says, that it’s some sort of trick, part of the ‘art.’ The use of discarded and found materials draws attention to the processes of making. The gallery becomes a workshop, or a sweatshop (I spend ages ironing T-shirts, others carefully/tediously stamp textpadpome postcards). Cheap white cotton T-shirts are stencilled with national stereotypes: ALL-DANES-ARE-HYPER-CONFORMIST-FASHION-VICTIMS; ALL AMERICANS ARE OBNOXIOUS; ALL AFGHANS ARE QUEUE JUMPERS. The blackboard invites guests/visitors to add more stereotypes eg south australians only have 4 types of love. Ihlein prints some of these during the exhibition, adding to the extensive collection.

INTER-ACTIONS: The work generates several special events and day to day interactions with gallery visitors which involve collaborators, ring-ins, and chance encounters. For instance, a screening of films about film (Samuel Beckett’s Film and Gustav Deutsch’s Film Ist) is introduced with a parodic discussion between local and interstate Beckett scholars (with EXPAT and EXPERT stencilled on their T-shirts) littered with false information, pretentious misreadings and spurious pseudo-debates. The screening is then ‘interrupted’ by a rare performance of AM Fine’s Piece for Fluxorchestra (1966)—24 performers recruited from local likely suspects. In the tiny Iris cinema (40 stuffed-tight leather seats) the work performs itself during the interval and is completed by unscripted interjections from a baby in the front row. In Event for Touristic Sites the exhibition takes to the streets during the Christmas Pageant, with Ihlein and collaborators bearing T-shirts stencilled with national stereotypings and armed with a digital video and Polaroid camera. Ihlein makes strategic use of local resources, from people to venues and events, in return making himself available to all and sundry, from dream researchers to community arts network meetings, to a local activist who also squatted in the gallery using it as a resource to make papier mâché guns.

IMMATERIAL: “The only 3d work I do is farming.” Artist statement. Contact letters fixed to the wall.

JUDGEMENT: The scattering of books and journals from the EAF library, along with Ihlein’s notes, work as a kind of open manuscript of work-in-progress showing sources and influences. The practice is performative and pedagogical, spontaneous and historical. From one of the typewriters:

6 crates filled with assorted reading materials ferdinand pessoa poems, ferrara poems, sausage roll 2.20 by simon barney, Dangerous Darwinism (‘i aint descended from no ape’), the chinese literary scene by Kai-Yu Hsu; Spine 3; Mafia for beginners; Audio on Wheels; The Australian Friday November 5th “free Trade Fight Against Terror” WTO in sysdney pic of a protestor (mid twenty sometting-backpack) being wrest hauled away by three police—one looking particularly peeved.”(sic.)

These are Ihlein’s footnotes, his referencing system.

“To settle on private land without pretence or title” is one of the more archaic definitions of ‘squat.’ The works and events at the EAF are fuelled by Ihlein’s engagement with the everyday politics and practices of squatting on disused private properties. In turning the gallery into his own ‘borrowed’ personal space, interactions with local artists and writers, gallery visitors, students and staff become key elements of the ethics and aesthetics of the event: Ihlein offers coffee and biscuits to gallery visitors and makes himself continually available for questions and discussions. It could sound horribly worthy but somehow he brings a light, playful tone that sidesteps the moralising often associated with activist art practices. He says the whole experience of living in the gallery and interacting continually with visitors, often for hours at a time, though productive, is also profoundly disconcerting and exhausting. There is a major ambiguity in this gesture: on the one hand, Ihlein’s desire to be present and to monitor and intervene in audiences’ responses to the work could extend the notion of artistic control by manipulating the reading of the work. However, it also involves gestures of hospitality, generosity and vulnerability: a politics of networked exchange and encounter. Plans for future work include screenings of the Expanded Cinema [pioneering new media and multimedia] films of the late 60s and early 70s.

Lucas Ihlein, BILATERAL Residency and Exhibition, Experimental Art Foundation, Adelaide, Oct 25-Nov 16, 2002

RealTime issue #53 Feb-March 2003 pg. 31

© Teri Hoskin & Russel Smith; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

We are 19 artists from around the country. We have entered ART CAMP—a hothouse in a cold place, an engagement with strange new processes and eccentric new people, shacking up in buildings so identical that they could only have been built by the military.

We are in Wagga Wagga. (So good they named it twice, a joke Andrew Morrish told at least twice every day. Only he could pull that off and still be funny.) We declare interests in hybridity and collaboration. Aided and abetted by 6 artist/facilitators, several project staff and a regular flow of visitors we pursue the game plan: operate in close quarters, exploit provided equipment and stir like crazy.

There’s a 20-minute walk from the accommodation to the studio spaces. Distance makes surprising things possible. There are conversations to be had, alliances to make, happenings to plot, dinner and drinks to contemplate, hangovers to nurse, people to meet and places to imagine. There wasn’t enough time in today’s workshop to debrief, to regroup, and to imagine beyond the scope of that last exercise. What happens next? Can anyone suggest what can be done with 3 balaclavas, 4 walkie-talkies, a couple of video cameras, and an explicit body or 2? Let’s make a show, quick and dirty. It’s not such a big ask, and there’s no pressure, but as she leant on the bar one night, co-curator Sarah Miller firmly requested a revolution. Our time starts now.

For the first week Melbourne dancer Ivan Thorley and I watch the late news every night, waiting for a declaration of war on Iraq, waiting for World War 3, wondering what will happen here in Wagga Wagga in response. Will this elite artist think-tank come up with an effective intervention strategy—a performative weapon of mass distraction?

Week 1: We get into workshop mode for a few days. Technical and technology workshops (hardware and software) and performance workshops offered in response to our developing interests. A grab bag of ideas, exercises and ordeals, introductions into the aesthetics and personalities of the facilitators—the exquisitely rambling improvisations of Morrish, the laconic wit and DIY approach to projection of Margie Medlin, and the strategically timed eccentric pronouncements and lateral speculations of Derek Kreckler with his ever present camera. In these early days we meet the other artist/inmates on the floor in a controlled environment, steered towards new options to stock up the performative toolbox.