Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

WA’s newest multi-arts festival is the result of a partnership between the City of Swan and Artrage. Last year it was a satellite festival of the biennial Artrage, now Urban Edge is going annual in Midland, one of the fastest growing urban centres in WA. The program—built loosely around a wild west theme of “an imagined place of unlimited potential where the unexpected occurs and regular laws don’t apply”—comprises theatre, sound, visual arts, a huge street event and the Video Head project. The latter is a new media community project involving all the schools in the region. Artrage artists are working with 500 young people creating new animation and video works. As well, images of heads will be projected onto large inflated globes, attached to the roofs and exteriors of prominent buildings creating a new media installation, “with 500 young people seeing themselves inflated to the size of gods”. In a populist-cutting edge blend there’s a sound program mixing country music and some of the country’s leading improvisers. Nexus is a sound installation with “layers of interviews and cultural and social statistics and histories gathered from throughout Midland”. Swerve is an animation program created by Disability and Disadvantage in the Arts WA members working with digital artists. Core Sampler is a huge experimental dance/electronic sound/ digital projection event staged in an outdoor carpark with dancers, new media artists. Urban Edge shows new ways for the arts and communities to join in celebration. Nov 8-22

RealTime issue #57 Oct-Nov 2003 pg. 27

© RealTime ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

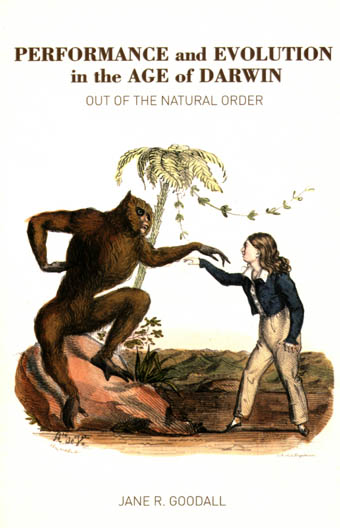

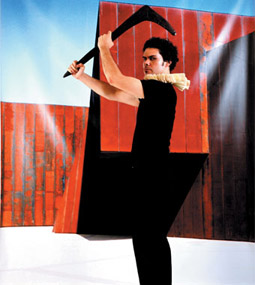

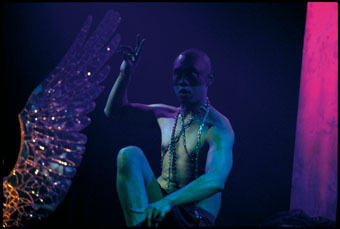

The Buiders Association & motiroti, Alladeen

The second national Time_Place_Space intensive workshop in the professional development of hybrid performance practitioners is underway in Wagga Wagga and the third is already announced for 2004, relocating to Adelaide mid-year and focusing on developing specific works as well as the critical, continued emphasis on process.

The impressive lineup of facilitators for 2003 includes Marianne Weems (Artistic Director, The Builders Association, New York), Andre Lepecki (author, dramaturg, New York), Marijke Hoogenboom (co-founder and dramaturg, DasArts, Netherlands), Michelle Teran (Toronto-based performance, installation and online artist), Margie Medlin (Melbourne-based filmmaker, lighting and projection designer) and Jude Walton (Melbourne-based dancer, performance-maker and installation artist).

The 2003 Time_Place_Space participants are a diverse group of practitioners, ranging from hugely experienced to relatively new, all with credentials in hybrid practices: Michelle Blakeney, Shannon Bott, Sue Broadway, Boo Chapple, Rosie Dennis, Simon Ellis, Ryk Goddard, Jaye Hayes, Cat Hope, Nancy Mauro-Flude, Mike Nanning, Michelle Outram, Deborah Pollard, Hellen Sky, Sete Tele, Douglas Watkin, David Williams, Fei Wong and Yiorgos Zafirio.

As I talked to Marianne Weems, the sounds of hammering and furniture shifting and mention of Meyerhold’s constructivism texture our long-distance phone call—The Builders Association is in the middle of moving office. Building is the right word for this unique multimedia performance company—since 1994 it has built work through collaboration internally and across continents. It builds new technologies and communication systems seamlessly into its work and new cross-cultural ways of looking at the globalisation we are living out in the everyday. Hopefully Weems’ visit will not only share strategies for creation but also begin building a relationship between Australian and North American performance communities.

Weems is a co-founder of The Builders Association and has directed all of their productions. Over the last 15 years in New York she has worked as an assistant director and dramaturg with Susan Sontag, Jan Cohen-Cruz, Richard Foreman, and many others. From 1988-94 she was assistant director and dramaturg for The Wooster Group. The Association’s current production, touring internationally (and destined for Australia in 2004) is Alladeen, a large-scale cross-media performance created as a collaboration with the London-based South-Asian company motiroti, directed by Weems and co-conceived and designed by Keith Khan and Ali Zaidi, featuring a cast drawn from both companies. It combines electronic music, new video techniques, an architectural set, and live performance to explore the myth of Alladeen, better known as Aladdin. The company describes the work as: “drawing on the lives of citizens living in the hybrid, global cities of New York, London, and Bangalore… Specifically, the piece will look at the contemporary phenomenon of international call centres where Indian operators are trained to flawlessly ‘pass’ as Americans. The performance will explore how we function as ‘global souls’ caught up in circuits of technology, and how our voices and images travel from one culture to another…The performance will alternate the contemporary world of the call centres—a web of technology in which the performers are operators—with spectacular, colourful fantasy sequences drawn from the Aladdin story and using the aesthetic of the early Hollywood and Bollywood Orientalist films.”

How do you go about creating a work?

One of things that has always been key to the way that we construct the projects is that everyone has all the equipment there from the beginning of the process, from the first day of “rehearsal” and even long before that. The designers are there with their technology assembled and that becomes a really integrated part of the process and is obviously not something slapped on in tech week…The only way I can function as a director is to have the sound and the video present. It’s not something you can storyboard and imagine and then hope it will work later, just as a performer has to be there for you to be able to see if they can do it or not, what the palette will be, what the vocabulary will be, how it can be articulated.

What happens before that?

Usually there’s a very long conceptual period, sometimes as much as a year that is interspersed with workshops. Alladeen is being created in collaboration with motiroti, and started with me and key members of the company meeting almost monthly (or even more with those other artists) face to face or by intercontinental phone conferences, trading back and forth a lot of email and drawing ideas from sketches and dramaturgical research and videos. Then I would get together with the artists in my company for about a 10 day workshop once every 3 or 4 months and that’s when we’d bring all the media together and, really, just make a huge mess and fool around and see if there was anything of interest that would emerge, say in terms of software that might be developed that would then inform the project or a direction to go in…for example in incorporating animation or a video vocabulary. That would be developed alongside the deepening research, with the video guys going off to a residency at STEIM (Amsterdam) or another place.

What is your role—monitoring, keeping the vision together and developing?

Pretty much all of the above. I try not to monitor, but I’m definitely participating in and articulating what they’re doing and reminding them of how it fits into the project. As they come up with things they bring them back to me and we decide together what is of interest, what is superfluous, what might lead to some other avenue. But pretty much everything the tech guys come up with ends up some way in the project. [Laughs]

It is said that collaborators all perform in a Builders Association show.

The whole ensemble really is about performativity and the technicians are often on stage and the audience watching them work and interact with the performers is as important as watching the actors act–they can’t exist independent of each other, so the sense of them working together to create this spectacle has become a signature for the company–they get constumed and are very visible.

What is it about spectacle that attracts you?

It’s a dialogue that’s been going on since Meyerhold and before with theatre artists threatened by or engaged in a dialogue with mass media and it’s certainly undeniable that you have to come to terms on some level with what is dominant cultural language–television, film and mediamatic culture, it’s certainly not theatre. We certainly don’t have to but it’s part of my interest in the culture’s interest in screen culture, to investigate it on stage and take it apart as much as we can. It’s one of the great advantages of this kind of theatre to be able to look at the stage as a kind of laboratory where you can see what live entertainment still means, what performance is as opposed to mediatised performance and putting those things together in a kind of last gasp experiment of why is performance. I want to unpack all that onstage. I’m certainly not head over heels in love with spectacle in a naive way but like any other good American I have a love-hate relationship with the undeniable glory of spectacle.

How important is cross-cultural collaboration to the company?

We’ve done a lot of work in Europe and pretty much created our reputation and stayed alive by working live there over the last 10 years. We worked for 6 months or more in Switzerland in a cross-cultural collaboration-in many ways it was much more of a foreign experience than working with motiroti. But this our most significant cross-cultural collaboration to date because there have been so many artists involved all over the world, from India to Pakistan, Germany, Sri Lanka, Trinidad… One of the things that has been so heartening has been the ongoing scope of the project, that it continues to snowball. There’s more touring coming on board. There’s a website with many people all over the world logging on. There’s a music video we made which will be playing on MTV India in the Spring. And that was the whole point of the project, to get outside of the theatre as far as possible and reach people who have no real interest in or access to the theatre. It’s been a big step for us but the nice thing about it is that there’s been no compromising of our aesthetic or my sensibility. Our interest from the beginning, and motiroti’s, was not to fall into the conventional multiculturalisms of the 1980s, but to really try to define what a multicultural collaboration could do. I think we’ve achieved some of that.

RealTime issue #57 Oct-Nov 2003 pg. 28

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Greg Leong, JIA

photo Andrew Charman-Williams

Greg Leong, JIA

Greg Leong is an established textile artist and designer. His inaugural performance, JIA (home) emerged from earlier exhibitions which explored his Chinese-Australian background through interweaving fabric and personal story. JIA is an ambitious move with Leong writing, performing songs, designing Princess Feng Yee’s costumes—including an original Peking Opera brocaded gown—and producing graphics incorporated into a panoply of screened images.Via chitchat and song, and through the personae of Closet Princess Feng Yee, Leong traces the emotional and intellectual hazards of his journey from Hong Kong to Tasmania. Directed by Robert Jarman, Princess Feng Yee stars in her own karaoke cabaret, with a theatricality that jibes and japes at the crude and the cruel. The targets are obvious, including Pauline Hanson’s racism looking for a policy, and the incipient exclusion each of us practices at different times in our engagement with the unfamiliar. Princess Feng Yee sings I Can Rrrrreally Rrrrroll My Rrrrr’s and we all sing along with Rrrrr’s rolling enthusiasm, laughing and wincing as we recognise our complicity.

Leong’s journey resonates with other iconic Chinese-Australian figures from public life and the arts, including William Yang, Dr Victor Chang, Bill O’Chee, Annette Shun-wah and Jenny Kee. JIA can be read as an implied paean to the success of these figures. It also uses elements of Leong’s own journey, tracing family connection and memory. Feng Yee revisits the old country in order to find out what and who she used to be. We “might be common, dowdy and so, so white” but this doesn’t prevent Feng Yee’s eventual return to Tasmania where she finally learns to call Australia home.

JIA incorporates diverse visual concepts imagined and created by Leong with technical direction by Andrew Charman-Williams. The audience is constantly drawn to the screen, in some cases necessarily so, after all this is a karaoke cabaret. The dilemma is that even the sumptuous and irascible Feng Yee is at times overshadowed by the constantly changing images. There are some wonderful visual moments including a shift from dense Hong Kong tower blocks pixellating away until the screen resembles the weave of cloth.

Through his hilarious, jostling commentary Leong continues to reflect and refract our dependency on tired icons. Feng Yee teaches us a Cantonese version of Click Go the Shears. We might be able to roll our rrr’s, but we are all at sea with Cantonese script romanised for our enunciation. Point made. We are bloody hopeless, and helpless with laughter. JIA is like nothing else we have seen or heard. Then again neither is Princess Feng Yee, who taunts with her basso profundo voice and fascinating on-stage costume changes. The culminating sequence is the Asianisation of Tom Roberts. Leong’s and other Chinese faces are superimposed on the hairy and sweaty shearers in Shearing the Rams, a classic moment of ringer/ring-in cultural inversion.

Greg Leong, JIA: a tale of two islands, Annexe Theatre, Launceston, June 26, Institute of Modern Art, Brisbane, Sept 4-5, Nexus Multicultural Arts Centre, Adelaide, Nov 21, Midsumma, Melbourne, Jan 2004, Goldsmiths College, University of London, Feb 2004

Leong’s work can be seen at Gallery 4A, Sydney until Oct 19.

RealTime issue #57 Oct-Nov 2003 pg. 29

© Sue Best; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

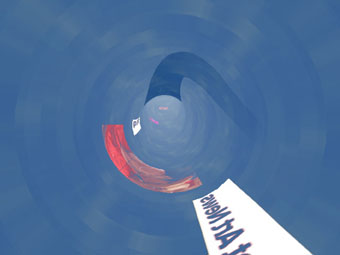

Anita Johnson, Underland

Brisbane-based Anita Johnson is a multi-disciplinary artist working with new and old media. With a background in graffiti, illustration and music videos, she has been integrating these formal and vandal art styles into contemporary and interactive videogame technologies. Curious about “faerytale vs impossiblity”, her work “re-contextualises (un)familiar fragments into virtual (3D) pop culture nightmares and wonderlandesque daydreams.” In June 2003, she participated in a candy-themed residency in Canada, where she began development of the first in her Underland series, an immersive 3D adaptation of Hansel and Gretel. Underland is currently being developed into an online 3D environment filled with secret lands; the next instalment will be launched in early October, 2003. Johnson is temporarily based at The Banff Centre, in Canada, where she is collaborating with a team to develop educational science toys.

http://anitafontaine.com/content/

RealTime issue #57 Oct-Nov 2003 pg. 29

© RealTime ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

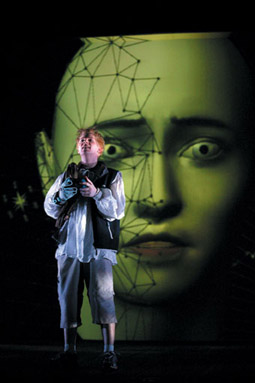

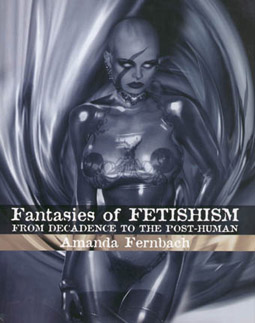

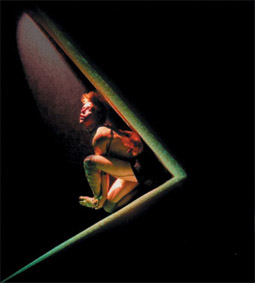

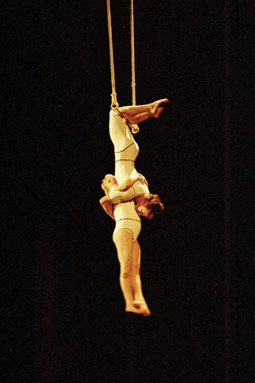

Cameron Goodall, The Snow Queen

photo Tony Lewis

Cameron Goodall, The Snow Queen

Windmill Performing Arts is an important new Adelaide-based national venture with international ambitions. The company’s Creative Producer Cate Fowler has had a long and significant history of creating and developing festivals and performances for young people in Australia. Fowler expertly brings together different creative teams for each of the company’s productions. The latest is a version of Hans Christian Andersen’s The Snow Queen celebrating the 200th anniversary of the writer’s birth. The concept for the show came from Wojciech Pisarek, the creator of the show’s virtual world, who writes, “The Snow Queen is a ruler of virtual reality and computer games rather than snow, frost and ice. We show 2 journeys and 2 different ways of gaining experience and knowledge. Gerda goes through the real world, Kay [a boy] through the virtual. It is not about which one is better, it is about a balance between them.” Based on his PhD research at Flinders University (see RT#52, p32 for a detailed account), “5 years of experimentation”, Pisarek says, “are to be tested for the first time in a commercial theatre production. The Snow Queen character is purely digital. Some characters will have both physical and virtual representation. All the 3D characters and the digital environment will run in real time–nothing is pre-recorded.” Pisarek describes this as “a scary exercise–we will have 2 independent computer set-ups to run the show, in case one crashes.” The Snow Queen is directed by Julian Meyrick, written by Verity Laughton, designed by Eamon D’Arcy and Mark Thompson, with music by Darren Verhagen. The eagerness of Windmill to engage with new technologies in works for new audiences is a sign of a healthy embrace of innovation.

The Snow Queen, Adelaide Sep 26-Oct 4; Sydney, Apr 22-May 9 2004

RealTime issue #57 Oct-Nov 2003 pg. 29

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Chi Vu

photo Ponch Hawkes

Chi Vu

Migrant writing, as Sneja Gunew pointed out some years ago, is often shaped by nostalgia, that psychic force that requires the subject to return repeatedly to the place of origin in the hope of recovering an identity that connects body, self and homeland. For the child of migrants, or those whose own memories are immature, the remembered country is secondhand, more or less a product of their parents’ nostalgia. If she returns to that place as an adult visitor, she must put together the childhood stories lived on the inside with a jumble of new languages, rhythms and sights that represent a different outside.

The premise of Vietnam: a psychic guide is that Vietnam can only be an imaginary location, as seen through the eyes of a young Vietnamese-Australian woman writing postcards back ‘home’ to Australia. “The journey of importance is not the physical one. The real journey is in the heart and in the mind.” Written backwards in a strange red book that becomes her tourist guide, this instruction is given to Chi Vu by a postcard seller. Her departures, her returns, from the City of Lakes, Halong Bay, Café of Babel, Hanoi or the City of Face generate poetic rhapsodies that attempt to capture fleeting impressions, to take snapshots or make song like the melodic tune of the plain brown birds. Indeed this performance began as a series of prose poems published in Meanjin. Although now in a stylish theatrical production complete with multimedia projections, the vignette-like format remains as the postcards are delivered–winged through the air by 2 chorus members at the beginning of each scene. Received by her father, played by older Vietnamese actor Tam Phan, and Jodee Murphy, as best friend Kim, Chi Vu herself appears as the narrator or as other kinds of cultural transmitter-postcard seller, motorbike rider, train traveller, café customer. Through them she carries the action—of discovery and excitement—whereas the other characters re-enact this different Vietnam, or with Murphy’s mime-dance style, animate the sensations of this new world.

In this committed bilingual performance, I enjoyed the musical, sometimes competing, layers of Vietnamese and English particularly when Tam Phan sings like an old crooner in both languages. A Vietnamese spectator noted that the Vietnamese was antiquated, far from the contemporary mix of North-South dialects and popular expression one hears in postmodern Vietnam. Perhaps the script reflects the proper speech of translator Ton That Quynh Du—also a long-term Australian resident—or that of the older male actor and thus its linguistics stand in for the 1950s voice of the father that Chi Vu knows. Rather than visiting a new Vietnam, it seems that the text oddly revives a traditional symbolic order.

By way of contrast, the computer graphics (Ruth Fleishman) project abstracted images of ponds, birdcages, or Oriental architectures as iconic shapes that slide up or down or open like barn doors. They flatten the landscape, leaving more space for the gap between a Vietnam lost and a Vietnam reconstructed to appear. This place remains overly idealised, and although we witness a momentary electrocution and the old man swallowing papers, it is difficult to locate this trauma either in her father’s history or in the young traveller’s streetscape.

While there is much experimentation with form, the performance never breaks from the circuit of nostalgia. Its structural repetitions give us too many beginnings and the endings tail away. I wonder if more speed or intensity could be accumulated by seeing where one image collides with another or whether the messages from Vietnam could psychically and physically disrupt the neat separation of ‘home and away.’ As a writer Chi Vu commands a delicate poetic register but this production makes me think that for each generation of migrant experience, the Greeks and Italians in the 1980s or the Vietnamese in 2000, the pleasure of returning might always be left in deficit rather than in credit. Particularly unless writing becomes a theatre of the present.

Chi Vu, Vietnam: a psychic guide, text Chi Vu, director Sandra Long, North Melbourne Town Hall, Aug 22-31

RealTime issue #57 Oct-Nov 2003 pg. 30

© Rachel Kent; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

A graduate of the Canberra Institute of the Arts (ANU), Somaya Langley is a composer, instrumentalist and digital artist. She also collaborates as radio presenter and producer on Therapy, the national electronica show on 2XX FM. Her interactive work, Disjointed Worlds (2000) is an email fiction that gently plots the psychic space between separated lovers. As a composer she ranges ably and inventively across acoustic, electroacoustic and digital domains. Langley is part of the HyperSense project (with Alistair Riddell and Simon Burton), who perform compositions in wearable flex sensor suits. The group recently appeared on ABC FM’s New Music Australia.

RealTime issue #57 Oct-Nov 2003 pg. 30

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Inside the Angel House (scheduled for a short season in November) is a new multimedia performance being developed by Theatre of Speed, a group of young performers with disabilities, as part of the Geelong-based Back to Back Theatre’s workshop program. The workshops, led by director Marcia Ferguson and animator/filmmaker Rhian Hinkley, are focused on the skill development in performance, improvisation, animation and photography. Just before he left with Back to Back for their European tour—he created the projected imagery that surrounded audience and players so powerfully in Soft—Hinkley wrote, “Theatre of Speed is an amazing opportunity to work with some of the most innovative and creative artists in Australia. The work that these guys create is unlike any other. I received a research grant from the Australia Council New Media Arts Board which has allowed me to spend more time with the group than I previously would have and to investigate the production of graphics and video that recreate Downs Syndrome…not as an actual representation of the syndrome, rather as an indication of the creative possibilities and benefits that genetic abnormalities can produce. The actors have had a chance to look at and use some great new technology which has been really exciting for all of us: a large Wacom tablet, a new G4 laptop, video projector, large screen TV, DVD players and burners. The actors take to new technology without any fear or preconceptions; this leads to really exciting levels of development that other groups don’t reach.

“The Wacom was really excellent for a number of reasons. Firstly, the actors loved the concept of being able to draw in multiple colours and with different brushes while using the same pen. Also the concept of filling areas in with a single click was something that really excited them. Another interesting element was the handwriting recognition with Wacom and OSX. This produced some really interesting translations and with a simple Applescript program I could make the computer translate their writings and then read it back in a number of voices.

“In producing the animations we used 2 processes. The first is hands-on, direct input and control by the actors. In this scenario the actors devise, create and animate the work. We did everything from basic cut-out and puppetry, from scratch animation directly on 16mm film to Flash from drawn animations. This produces raw and energetic pieces that are unpredictable and follow unique paths designated by the actors.

“The second process was to use myself as a tool and let the actors create works as directors or collaborators, giving them access to the full power of the technology. By directing me to make changes to their work or to create things for them we could work in 3D, and use software that is normally too complex to pick up within a short timespan. This resulted in works that have a slicker edge …but still retain the orginality of concept and direction.”

RealTime issue #57 Oct-Nov 2003 pg. 30

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Here is a new event on its second outing, and of major significance for Australian live art/performance art. The intensification of the relationship between Australian and international performance scenes is building rapidly with the emergence of Time_Place_Space (see page 28), the Performance Space-PICA-Arnolfini (Bristol, UK) Breathing Space connection, and the visits of Blast Theory (2002) and Forced Entertainment (2004 Adelaide Festival). The welcome consolidation of this rich pattern of exchange is more than evident in The National Review of Live Art Midland, Perth’s international festival dedicated to the presentation and exploration of live art practice. Established in 2002, the NRLA Midland is a collaboration between the City of Swan and New Moves International (UK), producers of NRLA Glasgow, Europe’s longest running and most influential festival of Live Art.

This will be an unconventional festival, with works that will take you beyond the niceties of neat timetabling into the time-space loop of durational performances and installations offering contemplative experiences, new ways of regarding the body, movement and issues of the moment. The program includes Hideyuki Sawayanagi (Japan); sculptor and performance artist Richard Layzell (UK), also conducting workshops; Dutch choreographer Angelika Oei and sculptor RA Verouden (with <> “in which a spinning dancer causes notions of time to vanish”), lone twin (UK) and Alastair MacLennan (UK, Professor of Fine Art at the University of Ulster) in a 5-day durational performance/ installation. With Edith Cowan University's School of Contemporary Arts, NRLA Midland 2003 has also commissioned new works by Perdita Phillips, Gregory Pryor, Domenico de Clario, cAVity, Lyndal Jones and Geoff Overhew and Singaporean artist Chandrasekaran. Nikki Milican, Artistic Director of New Moves International, will be on hand as will Mary Brennan, courageous and incisive dance and live art critic for the Glasgow Herald, conducting a workshop with local writers.

Midland Railway Workshops, Oct 22-26

RealTime issue #57 Oct-Nov 2003 pg. 30

© RealTime ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

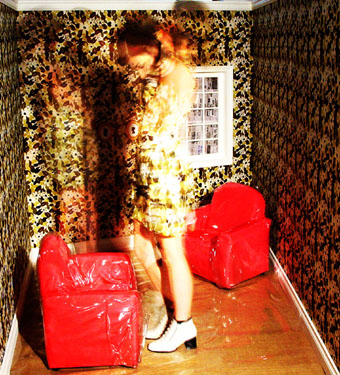

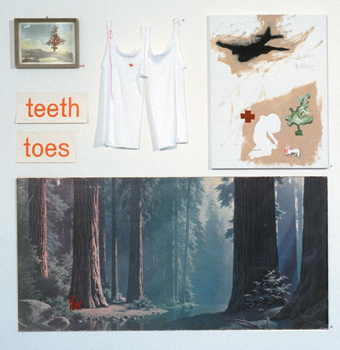

Sally Rees, video still, The Groove, 2003

Matt Warren is a multimedia artist who creates work for solo shows and collaborative pieces for performance installation and theatre. Awarded a Samstag scholarship in 1999, he completed a MFA at Simon Fraser University in Vancouver. He is currently a recipient of an Australia Council New Media Arts Board grant. Warren has recently returned from 8 weeks research in Germany and a grant from Arts Tasmania has enabled him to also work in the Czech Republic where he collaborated with a performance poet and an electro-acoustic composer to produce a performance installation for the Cultural Exchange Station total recall festival. Warren’s work has evolved from his initial explorations around the concept of absence, culminating in on the run (2002). His current concerns are exploring the ideas inherent in transcendence, the sublime and the supernatural. Sally Rees is a pop music fan who incorporates single channel video and installation in works that use autobiography and self-portraiture. Her recent video The Groove (2003) and research focus on popular culture through exploring the emotional investment of its consumer audience. Rees’ developing practice includes a newly discovered capacity to perform in her video projects. She aims to move beyond the constraints of the rectangular screen and develop richer ways of using and viewing the medium. Rees collaborated with Matt Warren on the theatre piece Pop for IHOS Experimental Theatre Laboratory in 2002.

RealTime issue #57 Oct-Nov 2003 pg. 31

© Sue Moss; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

I remember the video as intensely coloured and almost hallucinogenic in its rainbow effects. The idea of someone videotaping the sun has a pathos and strange logic that is a defining feature of Kajio’s work. Often an intensely colourful and multi sensory experience, Kajio’s work uses heightened video colour effects or coloured light reflections. In her 2002 exhibition Forest of Invisible Waves, at the Contemporary Art Centre of SA, installation components such as water showers, acrylic rods and mirrors were used to create an immersive space of reflected and multidirectional projected light. Sound was used throughout the space, further dislocating reality. Kajio writes, “Reality is not something that is perceived directly…My work usually plays on this abstraction or distortion to create a kind of space between the viewer and my piece, in which they can experience an alternative ‘reality’.” In 2003 Kajio curated Electtroni Nessun Senso, at Downtown Art Space. In her work for this exhibition projected light swims up the walls, LCD lights are refracted through a glass fish bowl with oxygen bubbler. One interpretation (there are several) of the exhibition title is “electrons with no sense of direction.” Yoko Kajio was born in Kyoto, Japan. Since graduating from the South Australian School of Art in 2000 she has exhibited in Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney, CACSA, the Physics Room and the Experimental Art Foundation. Kajio has also been a core member of performance art group shimmeeshok since 1998.

RealTime issue #57 Oct-Nov 2003 pg. 31

© Bridget Currie; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Jodi Smith is a writer, photographer and filmmaker whose video Redux? Part 1 was in the recent showing of Helen Lempriere Travelling Art Scholarship 2003 finalists at Sydney’s Artspace. After working in Australia, New Zealand and the US as a camera assistant on such films as The Matrix, Smith has been accepted to study for an MA in Fine Art at The Slade School of Fine Art in London where she hopes to make a feature length film. Redux? Part 1 plays engagingly with our knowledge of Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now and the constellation of masculine values that gravitate relentlessly around it. Smith remakes the first 6 minutes of the film, blending the original with carefully constructed scenes that mimic it closely but with a different protagonist—a woman. The effect is much more surprising and enduring than you’d first imagine. Smith writes, “Over the last year I have been dealing with the history of war and specifically how gender roles both define and are defined by war. A key issue within my filmmaking practice is the issue of female subjectivity—particularly the lack of it within the cinema and how this is a reflection of first world society.”

RealTime issue #57 Oct-Nov 2003 pg. 31

© RealTime ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Jane McKernan is best known for her work as one of The Fondue Set, which she founded with Elizabeth Ryan and Emma Saunders in 2000. McKernan’s solos work in a more subtle register, still confronting the audience but drawing us in to share delicate observations and actions. She performed in Mobile States last year in a powerful solo, I Was Here and took the ideas behind this piece to Dancehouse in July this year where she performed an improvisation at Dance Card, an informal season featuring 5 dancers each week. She also appeared with Eleanor Brickhill in Waiting to Breath Out at Antistatic 2002, at Performance Space in Sydney. McKernan currently has “a Sigourney Weaver thing” and is developing a piece with Lizzie Thomson called Working Girl.

RealTime issue #57 Oct-Nov 2003 pg. 31

© Erin Brannigan; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Video was one of the strongest components in the recent showing of Helen Lempriere Travelling Art Scholarship 2003 finalists at Sydney’s Artspace. In his finely shot and beautifully edited Pablo Velasquez Shoeboard Remix, Matthew Tumbers’ anonymous protagonist does everything you’d like to do with a skateboard— without actually using one. Feet skid assuredly across surfaces, the body twists and glides with the trademark crouch and angularity, the camera goes closeup on the virtuoso ride. Is this for real? Tumbers writes that his video “mimics and parodies a form, namely skateboard manoeuvers with elements of ‘street dance’, creating a fictional form that could well be real and achievable.” It’s pretty convincing, but the pleasure beyond surprise is in the dexterity of the very making. It’s a witty variation on other skateboard videos doing the rounds. Tumbers is a COFA graduate who has exhibited solo at Block and TAP galleries and whose Gumnut Xanadu 3: Expanding Conglomerates opens soon at Kudos Gallery.

RealTime issue #57 Oct-Nov 2003 pg. 31

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Why is bad theatre so excruciating? Why is it so much worse than bad film? This question vexes many of us who spend a reasonable amount of our professional lives sitting in uncomfortable spaces enduring the slings and arrows of tragic theatre. So when the word gets out that something good is happening, we are prepared to endure a stinking hot night and a venue renowned for back-breaking seating and zero oxygen. Who and what was the cause of all this selfless devotion? Blame Matthew Lutton, whose outstanding physical and truly absurd production of Ionesco’s The Bald Prima Donna, had audiences in raptures during the 2003 WA Fringe Festival. Not surprisingly, it was awarded Best Fringe Production.

Lutton has packed a lot into his young life. At a mere 19 years of age, his credits include director, writer and performer. As a performer, he has been clown, acrobat, puppeteer and actor. With his company, ThinIce Productions, he has adapted and directed several productions. In 2002, he wrote and directed the sell-out physical theatre piece Trading Fates at the Blue Room Theatre and presented a self-devised work at PICA during Putting on an Act. So far this year, Lutton has directed the epic masked production of George Orwell’s Animal Farm and worked as assistant director on Be Active BSX’s Six Characters in Search of an Author and Black Swan Theatre Company’s The Merry Go Round in the Sea. In 2004 he is looking to direct Bed, a new script by Sydney writer Brendan Cowell in a multi-dimensional, audio visual and visceral production at PICA. Lutton is definitely across the boards (sic). He has just been appointed Director of BSX, a company for young artists producing new and contemporary theatre works with professional support from Black Swan Theatre Company. Oh, did I happen to mention that Lutton is currently completing his 2nd year of Theatre Arts at WAAPA. Long live good art.

RealTime issue #57 Oct-Nov 2003 pg. 32

© Sarah Miller; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

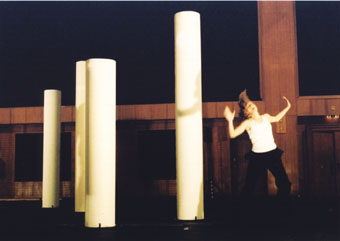

Stephanie Lake

photo Virginia Cummins

Stephanie Lake

Melbourne has been a centre for muscular, bony and often violently articulated choreography. Stephanie Lake is not new to this scene. She has danced for Phillip Adams (balletlab), Lucy Guerin, and Gideon Obarzanek (Chunky Move), and the influence of all 3 choreographers can be seen in her own pieces. Now that the physical characteristics of this trend within Melbourne dance have become fairly well defined, there has been a return to theatricality amongst such practitioners and it is here that Lake’s distinctiveness is most apparent. Her work is closest to Adams’ in its movement style and dramatic, violent energies, but if Adams’ dramaturgy is as much defined by the juxtaposition of theatrical ideas and elements as by anything else, then his is arguably a non-aesthetic, rather than a style per se. As such, this broad field of dance leaves plenty of room for Lake to invent her own mad imagery and strangely funny, off-kilter scenarios. Lake’s full-length work Love is the Cause (2001) represents the summit of her independent career to date, while her short study The Loop was the highlight of Chunky Move’s recent Three’s a Crowd program (2003) and exhibited considerable potential for development in its wryly angular, contemporary ballet. Lake has also collaborated with James Brennan on his staged events (namely Piglet, 2001). In the spaces between theatre and dance, surreal comedy and the avant-garde, Stephanie Lake has emerged as an important and invigorating new artist.

RealTime issue #57 Oct-Nov 2003 pg. 32

© Jonathan Marshall; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

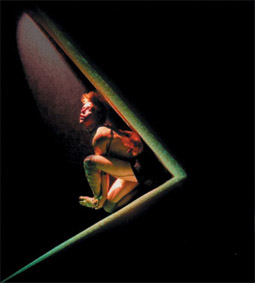

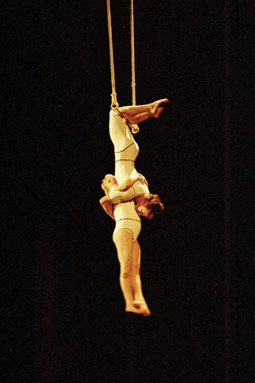

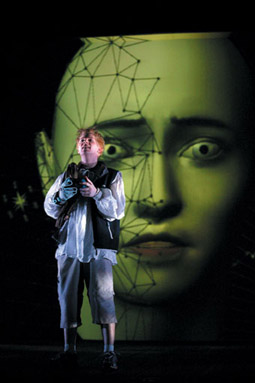

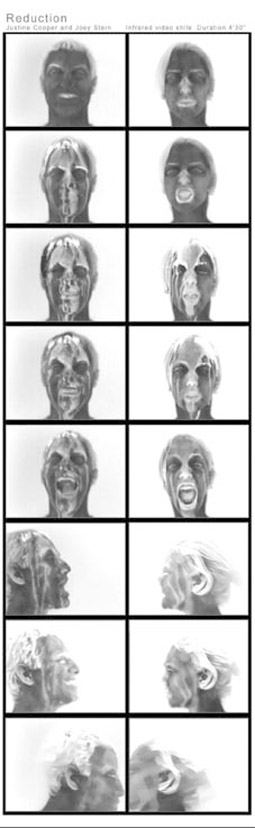

Ninian Donald The Obcell

photo Mark Gordon, Garry Barnes

Ninian Donald The Obcell

Fiona Malone’s career is a model of multi-skilling . She’s worked in Australia and Europe in all manner of dance forms from folkloric to dance theatre to movement research with an abiding interest in live multimedia performance. Before joining the Australian Dance Theatre in 2000, she toured Europe for 5 years with Belgian multimedia dance and technology company, Charleroi Dansers directed by Frederic Flamand. Last year, as well as being nominated in the Outstanding Female Dancer category at the Australian Dance Awards for her performance in the ADT’s The Age of Unbeauty, Fiona presented her site-specific work Bamboo Bathing at the Contemporary Art Centre of SA. Recently she spent a month in Birmingham as part of the DanceExchange program working with choreographers Henry Oguike and Akram Khan on the research and development of new ideas and movement.

This year Fiona was awarded an Australian Choreographic Centre fellowship to develop The Obcell, an interactive dance/theatre/multi-media performance addressing issues of human testing, manipulation and solitary confinement. The dancer wears the Diem Dance System, a new sensor-based technology designed for the use of dancers and composers at the Danish Institute of Electro-acoustic Music. Stage 1 of The Obcell was presented in the Risky Manoeuvres season at Canberra Theatre Centre earlier this year. In September, Stage 2 manifest as a collaboration between Malone and 4Bux:Progressive Arts, another multi-faceted Adelaide outfit. Performed by Ninian Donald with sound and technology by Peter Nielsen and dramaturgical input from director-designer Ross Ganf, early response suggests that while the themes of The Obcell need some refinement, the use of multimedia in live performance makes this a team to watch.

RealTime issue #57 Oct-Nov 2003 pg. 33

© Virginia Baxter; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Rachael Guy, Doughboys

Over the past decade Rachael Guy has worked across several disciplines. Formally trained as a visual artist, her voice has been in demand in contemporary music theatre circles and she has been a soloist in Ihos Opera productions. Writing is another passion. For a long time Guy has wanted to create a body of work that incorporates all these practices. She began exploring the concept of adult puppetry and in 1999 produced a series of erotic dolls with highly detailed porcelain heads and hand stitched lingerie bodies. Disquieting and fascinating to look at, these little figures became conduits for Guy's themes of transgression, appetite and ambiguity. Seeing them in an installation, or being held or regarded by people (usually with a mixture of curiosity, revulsion and humour), gave her the idea for Torrington’s Buttons, a solo show which will lie somewhere between performance art and theatre. The piece provides a vehicle through which Guy explores her experience as an adolescent, grappling with a sense of acute isolation in the suburbs of Launceston and how she dealt with this by forming an intense emotional and imaginative attachment to a deceased sailor (a member of the Franklin Expedition to find the Northwest Passage in 1845-8). In 1986, the perfectly preserved remains of the young sailor, John Torrington, were exhumed from permafrost. His image appeared in the media and struck a profound emotional chord with Rachel Guy during a difficult adolescent period. She intends to tell this story of adolescent love survival through a theatre work that combines narrative, song and puppetry in a minimal theatrical setting.

RealTime issue #57 Oct-Nov 2003 pg. 33

© Susanne Kennedy; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Compared critically with brilliant artists DJ Shadow, The Beastie Boys, Tricky and David Lynch, The New Pollutants are making a big impact on the live arts scene in Adelaide and beyond. Featuring the talents of Benjamin Speed aka Mr Speed (vocals), and Tyson Hopprich aka DJ Tr!p (the 8-bit Wonder), The New Pollutants are intellectual hip-hop with an experimental edge. These guys have their own sound, it’s global and it’s local and it has evolved from who these artists are. In this sense, the experience of their work is intimate, leaving their audiences gasping—for air and for more! The New Pollutants recently

released their independent EP at Minke Bar in Adelaide—Urban Professional Nightmares, following their critically acclaimed debut album Hygene Atoms. These guys take lo-tech augmentation to the extreme, using the obsolete Commodore 64 S.I.D. Chip soundcard in the bedroom studio. The resulting sound is altered, embracing lo-fi technology with a familiar flavour. The New Pollutants are best experienced live, where the sensory atmosphere is addictive and the beats are phat. The live experience integrates visual experiments with original sound and a theatrical, interactive edge. The New Pollutants produce an honest sound with grounded ideas driving the creation of their work. There’s no doubt these guys are going to be huge, but only as huge as they want to be.

RealTime issue #57 Oct-Nov 2003 pg. 33

© Rachel Kent; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Pseudo Sound Project is an experimental fusion of DIY technology within performance initiated by SA-based media artist and event-architect Kristian Thomas. PSP has evolved over the last few years in a progression of rooftop performances, clubs, artist-run galleries, festivals and master classes, in collaboration with local and internationally-based video artists and musicians. With a love for the techno-aesthetic, Thomas’ performances are obscure and bombastic, slipping between glitch-pop, the moving image, hardcore electronica and rhythmic nature sampling. With a wide variety of electronic video and audio artists invited to PSP events, Thomas’ performances are chaotic, sublime and often grating, impressing upon his audiences a predilection for real-time experiences bordering on the spiritual. As a travelling performance sphere, the techno-playground of Thomas’ iconic mobile icosahedron rig stands in sharp relief against natural backdrops, yet with an obvious reverence for the chosen landscape. Nature themes have figured prominently within many PSP festivals and shows, with PSP no 8 featuring the successful planting of 1000 native trees. Pseudo Space is an interactive gallery and shop set up by Thomas and his partner Kerry Scarvelis, a cool-hunting nu-fashion designer. Pseudo Space is a home base for PSP events, outlet for local moving art, electronica and emerging designers. It’s also the sole distribution point for Thomas’ unusual beer recipes. Blends such as VegieGarden–a wheat beer with coriander and orange–notorious to the regular patrons of Pseudo Space opening nights, has recently caught the interest of brewers and local café owners. With a smattering of Epicureanism and an ardour for all things glitchy, Pseudo Space has added some vigour to the quickening pulse of experimental art, design and hospitality in South Australia.

RealTime issue #57 Oct-Nov 2003 pg. 33

© Samara Mitchell; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

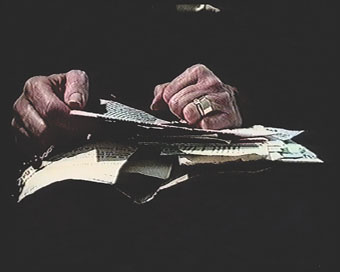

Rainer Mora Mathews, Dead Lions

Rainer Mora Mathews has exhibited as a cartoonist since he was 10. Now in his late 20s, he’s been working on Dead Lions (from the verse in Ecclesiastes: “for a living dog is better than a dead lion. For the living know that they shall die, but the dead know not anything”) for several years. It’s extraordinarily ambitious: a 300-page investigation of how we relate to our ancestors. The narrative stems from Mora Mathews’ fascination with his own ancestry: the experiences of his father’s family as Jewish Holocaust survivors and his mother’s Australian forebears’ role in removing Aboriginal people from their land.

Woven into this narrative is a series of archetypal myths from the Jewish and Western European tradition that reflect on ancestral relations. The comic form, which is a key creative paradigm for Mora Mathews (“this is not a novel nor a storyboard for a film”) enables a visual progression through which the ancestors or ‘dead lions’ take shape in the background, becomingly increasingly involved with the ‘live’ action in the foreground. This isn’t visual philosophy of the ‘Freud for Beginners’ variety but the telling of stories in ways that elicit philosophical reflection. The fusion is understandable. Mora Mathews’ mother, Freya Mathews, is one of Australia’s leading eco-philosophers. His father, Philippe Mora, the filmmaker, once drew comics, and his grandmother, Mirka Mora’s paintings seem strongly influenced by the comic form. Rainer Mora Mathews has hibernated north of Bendigo for the past 6 months, finishing his opus. Dead Lions is an epic of the Euro-Australian experience.

–

RealTime issue #57 Oct-Nov 2003 pg. 34

© Richard Murphet; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Frances Rings is an experienced dancer who is now emerging as a significant choreographer. She joined Bangarra Dance Theatre after graduating from NAISDA in 1993, 2 years after Stephen Page became artistic director. She performed in Page’s first full-length work, Praying Mantis Dreaming, and has continued to dance with the company, developing a remarkable onstage partnership with the late Russell Page. In 1995 she studied at Alvin Ailey American Dance Theatre, an experience that has strongly influenced her dancing and choreography. Ring’s first major choreographic work was Rations for the 2002 Bangarra double bill Walkabout, a narrative piece including an inventive use of props. Her pieces in the recent Bangarra work Bush were standouts: Slither, Stick and her own solo, Passing. Clear and inventive choreographic themes combined with traditional subjects in Slither and Stick, the latter featured a very effective use of stilt-like props, while Passing read as a moving eulogy for her former dance partner. As artistic director, Stephen Page encourages his dancers to develop their choreographic skills and this is evident in the opportunities he has given both Rings and Albert David. Rings has 2 major choreographic projects lined up for the coming year and is clearly keen to continue developing her craft both inside and beyond the Bangarra fold.

RealTime issue #57 Oct-Nov 2003 pg. 34

© Erin Brannigan; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

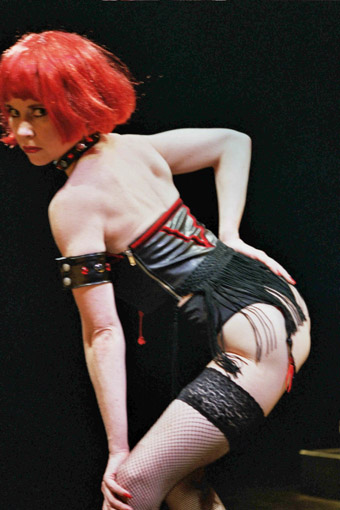

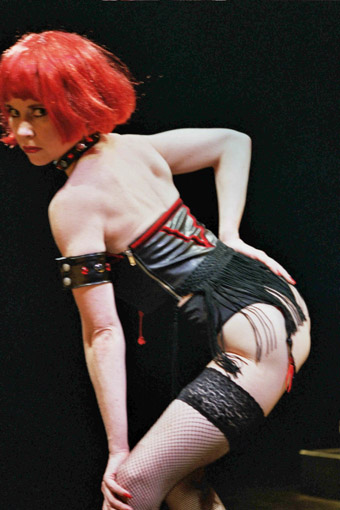

SacredCOW (Dawn Albinger, Scotia Monkivitch and Julie Robson) The Quivering

photo Suzon Fuks

SacredCOW (Dawn Albinger, Scotia Monkivitch and Julie Robson) The Quivering

SacredCOW (Dawn Albinger, Scotia Monkivitch and Julie Robson) is a Brisbane-based theatre ensemble that formed in 2000 to devise adventurous performance with strong physical and sonic scores. As they explain, “While touring and salsa dancing in the wild zones of Colombia, we dared each other to work together for 30 years.” And they’ve taken the dare seriously by establishing clear long term aims and direction for sustaining their fruitful collaboration. Inspired by “divas, lamenters, lullaby-makers and monsters”, SacredCOW became part of the Brisbane Powerhouse Centre for Live Arts’ Incubator program, designed to support local artists working on long-term laboratory style training and performance building. From here, the ensemble worked with Sydney-based director Nikki Heywood to devise The Quivering: a matter of life and death. SacredCOW’s creative partnership for The Quivering has since grown to involve Mount Olivet Hospice and the Creative Industries of Queensland University of Technology. With a history of assistance from Arts Queensland, the Australia Council and Playworks, The Quivering is scheduled for full production and a 2-week season at the Brisbane Powerhouse in November 2003. SacredCOW are also co-founding members of Magdalena Australia, part of an international network of women in theatre, and were coordinators for the recent International Magdalena Australia Festival in Brisbane.

RealTime issue #57 Oct-Nov 2003 pg. 34

© Mary Ann Hunter; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Like Camilla Hannan, Thembi Soddell is a grit/throb/atmosphere artist whose compositions featured in the early work of RMIT’s ((tRansMIT)) collective, helping to establish the Liquid Architecture festival. Where Hannan’s sound and installation work often has a cinematic, foley quality, laid out within spacious, hissy caverns (eg 4-Way Dam in 360 degrees: Women in sound, 2003), Soddell’s is arguably more abstract and mysterious. Her most recent piece—the superb installation Intimacy (also in 360 degrees)—was characterised by sudden jumps and cut-offs in sound, stochastic drop-outs in volume which revealed, on subsequent listening, a pre-existing subtext of sound now rising within the mix. The setting of Intimacy within a dark, claustrophobic alcove, bordered by heavy, red felt curtains, exaggerated its erotic and, at times, genuinely frightening trajectories. Soddell’s CV reveals her particular interest in the subconscious, psychological transformation of sound and space, which she prompts in the listener using processed field recordings and by exploring thresholds of perception. From an apparently ‘silent’ audio space comes a terrifying point of sound which then vanishes before it reaches such a conclusion that allows tension to be released. Although Intimacy represents the summit of this approach, Soddell has been moving towards it in pieces featured in the Document 03-Diffuse compilation (Dorobo, 2001) and the gallery showing and recording Gating (West Space, 2002). In her frightening fluxion between the organic (processed water sounds, air, etc) and the electronic, Soddell incites tense listening.

RealTime issue #57 Oct-Nov 2003 pg. 37

© Jonathan Marshall; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Sebastian Moody from 100% expression

In the text-based practice of Brisbane emerging artist Sebastian Moody there is a consistent concern with viewers and their reactions. With gestures both grand (such as the imposing statement “BUILT UNDER THE SUN” at Brisbane’s South Bank) and slight (the text “Primal man craves fire‚” posted in newspaper personal classifieds), Moody continually seeks a response, and considers each a little victory. However the response Moody seeks is never specific as his text works are fragmented, ambiguous and their precise intent continually debateable. What is important then, when encountering Moody’s work among the city’s landscape of advertising slogans, is the priceless freedom of choice that they wish to provide. In his most recent exhibition Generation: Point, Click, Drag, produced collaboratively with Craig Walsh as part of Moody’s 2003 Youth Arts Queensland Mentoring Program, the significance of the viewer’s response was again highlighted. Presenting gas masks and body bags emblazoned with the Nike logo, Walsh and Moody questioned the legitimacy of the audience’s, and also their own, ideological freedom within contemporary historical, social and economic contexts and the War on Iraq. Linking recreational sport and the war on terror, the show suggested the game of our current condition and the possibility that only a finite set of choices and responses exists. This gesture, intending to provoke a response, was not however predetermined as perhaps the response which commodity slogans endorse or games sanction. Rather, in his practice Moody seems to continually seek to conserve the reader’s free will in this increasingly authoritarian society.

RealTime issue #57 Oct-Nov 2003 pg. 39

© Sally Brand; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

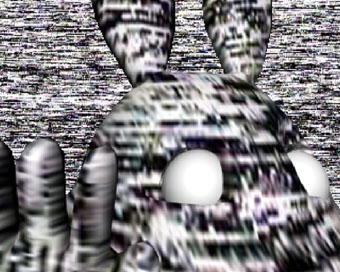

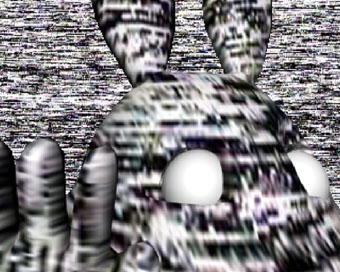

Mel Donat, Memory Play Back

Combining the warmth of analogue audio and video equipment with the calculated cool of their digital offspring, 4 Sydney artists explore a range of transitional/crossover/meeting points—between sound and image, personal and public, past and future, remembering and forgetting, observer and observed… Andrew Gadow, Mel Donat, Tim Ryan and Phil Williams emerged from Honours level electronic arts studies guided by senior lecturer Peter Charuk at the School of Contemporary Arts, University of Western Sydney. This year they will have an exhibition, Digital Decoupage, at First Draft Gallery, December 3-14. With varied interests, they work separately as well as on collaborative projects.

Gadow explores the translations from sound to vision and vice versa, generating pulsating video images from analogue synth keyboards, and making sounds from video footage. Most recently he exhibited in Tracking at Bathurst Regional Gallery. Gadow’s next appearance is at the upcoming Electro-fringe festival in Newcastle. Donat, working primarily in animation and installation, uses “subversion and contradictions to explore issues that may be considered disconcerting.” The installation—to be shown at First Draft—Memory Play Back, incorporates a hand-made soft toy rabbit, which operates as an interactive interface via which the viewer manipulates 3D imagery and sound. Donat’s experimental piece Trigger Displacement screened in the 2003 St Kilda Film Festival. Williams works mainly with sound in performance and installation, and for Digital Decoupage he continues with themes developed in the recent installation approaching silence at Casula Powerhouse, “a site specific meditation on the pursuit of absence.” Ryan’s work is a kind of minimal video. His Crash Media is currently touring New Zealand in the show Dirty Pixels. Ryan says the new piece, Future Proof, is concerned with ideas of obsolescence in the digital age.”[I]n this work I use defunct and faulty video technology to de-construct analogue footage.” Future Proof will show in Digital Decoupage in December, and, with Donat’s Bathing in A Warm Glow of Nothing will also be exhibited in Brainfeed at the Penrith Regional Gallery and Lewers’ Bequest, Oct 5-Nov 30.

RealTime issue #57 Oct-Nov 2003 pg. 39

© Linda Wallace; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

TV Moore, The Dead Zone

In a small, darkened sideroom in Sydney's Artspace, 2 large screens face each other. You sit on a padded seat between, turning to take one in and then the other, adjusting to 2 close views of a man running slo-mo through an empty Sydney CBD. Because he’s running backwards and because the speed isn’t modified to the point of mere artifice, and because the man keeps turning his head to see where he’s been/heading, there’s a loping anti-gravitational lyricism to The Dead Zone that adds to the doomsday suggestiveness of empty streets and time undone. Or, as Moore notes, “this barefooted man is certainly terrified but perhaps he is in fact running from himself.” The work was exhibited at the recent showing of Helen Lempriere Travelling Art Scholarship 2003 finalists at Sydney’s Artspace and was Highly Commended by the judges. With relatively simple means, Dead Zone exploits our cinematic awareness to maximum effect, multiplying meanings in a short time and lingering much longer than its 3 minutes 30 seconds duration. We’ll be watching more TV Moore.

RealTime issue #57 Oct-Nov 2003 pg. 39

© RealTime ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

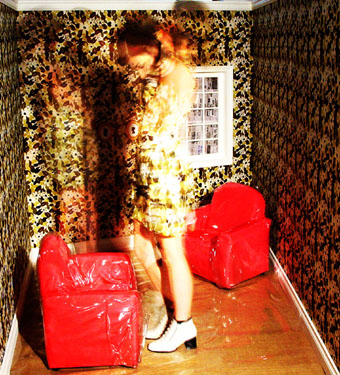

Anna Tregloan

It is apt that, among other projects, theatre-maker Anna Tregloan is adapting the writing of Borges. Like Tregloan, he often employed spatial devices as metaphors for social, philosophical and literary ambiguities: a map so detailed that it covered the landscape it represented, the library as labyrinth. Tregloan’s most recent piece is the still-embryonic performance installation, The Long Slow Death of a Porn Star. Along with design commissions ftom Danceworks, Circus Oz and The Three Interiors of Lola Strong, Tregloan has been devising her own installation-like productions such as Mach (2000) and Skinflick (2001). LSDPS is partly a sequel to the latter, in that both employed a series of voyeuristic scenarios to produce wonder, unease, discomfort, pleasure and seduction. Context and conjunction produce the theatrical content here.

In Skinflick the audience charmingly and somewhat vulnerably observed the performance at eye level, with their heads extending to the height of the stage from beneath the rostra. The staging of LSDPS was less restrictive–the performance had no formal beginning or end, offering spectators several linked spaces to traverse, or rest within. At the top of a staircase, beyond a tight hallway, and through a doorway draped with bordello-esque beads, lay a snug viewing hall peppered with mounted illustrations. At the other end sat a foreshortened recreation of a 1950s/60s chic domestic interior. To one side lay a small, white room containing a mounted crayon, endlessly describing a circle. In the hall before entering, a sign signalled that all objects were for sale, with a description and price of each. Art as stylish sexual commerce.

Within the toy-like domestic annex, 2 women–saturated with a sublime ennui-idly posed, gazed vacantly outwards, or collapsed in upon themselves and 2 little chairs. Much of the ‘action’ was provided by David Franzke’s gently scorifying, contemporary musique concrète score, composed of sounds of breath, inflation, deflation, moans, crackles, laughter and something akin to male masturbation.

It has been argued that pornography is inherently avant-garde because, to infuse viewers with feelings of masculine potency, pornographers strive to represent female orgasm, allowing the viewer to fantasise that he has produced this reaction in the subject of his gaze. Femal orgasm is however impossible to satisfactorily represent visibly or audibly. Despite the apparent explicitness of pornography, what makes something pornographic is in fact precisely what remains forever absent but alluded to within pornography itself. Tregloan’s interaction with and referencing of pornography (presented in a book available within the performance space) was not particularly satisfactory, but in producing this sense of pornographic absence, both Skinflick and her newer project were wonderful successes. Sex is never visible in Tregloan’s works, but it is one of the themes she virtuosically recreates through staging an absence of overt action, associated with a dark, explicitly voyeuristic audience relationship. Her circle-drawing machine was, in this context, the quintessential pornographic object, its aesthetic frottage terminally spirally around issues of sex and the feminine grotesque.

The Long Slow Death of a Porn Star—The prequel, director/designer/concept Anna Tregloan, performers Caroline Lee, Victoria Huff, music/sound David Franzke, Hush Hush Gallery, July 23-25

RealTime issue #57 Oct-Nov 2003 pg. 40

© Jonathan Marshall; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Christian Bumbarra Thompson

On a balmy dry season Parap Market morning in August, Brenda L Croft (photographic artist and Senior Curator, Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Art, NGA) opened Emotional Striptease and reaffirmed Christian Bumbarra Thompson’s status as one of the youngest and brightest ‘blak’ stars to emerge from the Boomalli ‘mother-ship’ into the galaxy of successful Indigenous photomedia artists including Destiny Deacon, Fiona Foley, Leah King-Smith, Tracey Moffatt, Darren Siwes, and, I would add, Croft herself.

From a Darwin perspective, both the timing and subject matter of the show were significant. Emotional Striptease coincided with the 20th National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Award–long dominated by contemporary Indigenous art from remote communities throughout the Northern Territory and Western Australia. In the current ‘future shock’ climate of new media art, work from these regions may be regarded as ‘traditional’—in style, medium and content—but historically its claims to country are as politically powerful as the most confronting work from the cutting edge of the metropolis. Concerned with the interplay of meaning between objects, space and history, and Western culture’s (mis)representation of Indigenous Australians, Emotional Striptease is a provocative rebuttal to any institutionally-prescribed notions or categories of ‘blakness.’ It highlighted a contemporary Indigenous art practice which has not, until recently, received the local institutional recognition and public exposure it deserves–and unequivocally demands.

A Bidjara man of the Kunja Nation (southwest Queensland), Bumbarra Thompson was born in Gawler, South Australia, in 1978. He is also of German Jewish heritage. His art school training was in sculpture and installation. He spurns art historical classification: “my work, like myself, is in a constant state of flux.” Study in Melbourne, where he resides, has had an obvious influence on the ideological underpinning of his art and the cosmopolitan rubric of his catalogue essays.

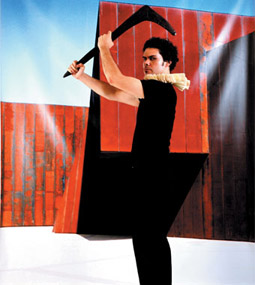

At 24HRArt, Bumbarra Thompson ‘performed’ his Emotional Striptease in an installation comprising 7 large-scale, hyper-real colour photographs, each depicting a young Indigenous man or woman (including himself), variously robed in chic Melbourne’s trademark black or in a variety of costume props reminiscent of Victorian stage dramas or historical paintings. In a series of carefully choreographed poses and hand gestures, each figure holds an exquisitely incised and ochred Aboriginal artefact—a parrying shield, fighting club, woomera or boomerang. Like Caravaggio, the artist has chosen ‘models’ from his own world: friends and colleagues living and working in Melbourne. Set against the architectonic backgrounds of Melbourne’s key ‘cultural spaces’ (Federation Square, the Melbourne Museum, ACCA), the figure-in-landscape compositions collectively create a new Melbourne—one that reclaims that city as a reconstructed site of ‘blak’ urban identity. Three larger photographs, depicting close-ups of architectural façades, comprise the theatre ‘wings’ of a highly charged mise en scène.

Although tilting at the 19th century studio practice of ‘capturing’ Indigenous subjects in picturesque landscape dioramas and the ‘scientific’ role of photography in colonial ethnography, the iconography of Emotional Striptease contains echoes of other, earlier sources, principally art historical. One female figure bears a parrying shield, her white-gloved hand resting above the abdominal swell of her black hooped skirt. She stares back at the viewer with the dignified stillness and ritual solemnity of Piero della Francesca’s frescoed ‘urban’ Madonnas. Of all the male portraits, the most powerful image is of Bumbarra Thompson himself. His eyes seek the viewer’s with the intensity of one of El Greco’s ruffled-collared courtiers, fists clenched around a hooked, ‘number 7’ fighting boomerang, bare arms raised against a black/red façade–the traditional colours of revolution and resistance. Like a ‘blak’ avenging angel, wielding a potent artefact from the archival past, he annunciates an unmistakable message of self-determination for the present and future: boomalli–to strike, or make a mark.

–

Emotional Striptease, Christian Bumbarra Thompson, 24HRArt Northern Territory Centre for Contemporary Art, Parap, Aug 16-Sept 6

RealTime issue #57 Oct-Nov 2003 pg. 40

© Anita Angel; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Irene Torres, Untitled 2003

A lot of art arrives in the mail at the RealTime office—on cards, disks, paper, acetate, vinyl, wood. We also receive key-rings, balloons, small packages (a tiny bag of sand arrived recently with the word “Escape” on a tag inside) and another day, a hand-painted box containing a pistol in papier-maché. Something about the moody postcard image from first site, a gallery with a strong commitment to emerging artists, stopped me opening mail this particular August morning. It showed the work of Irene Torres, a 22 year-old RMIT drawing student currently completing her honours year who featured with others in first site’s Recent Works exhibition. Torres speculates on the found photograph “as a representation of the experience of others in relation to [her] own.” She makes photocopies of these lost images and draws them (literally) into mysterious worlds. Occasional words and names are scratched into the grainy surface—“a gesso ground layered with various mediums, mainly graphite, acrylic paint, charcoal and pastels applied to pieces of MDF board.” Inspired by artists like Louise Bourgeois (especially her book of family photographs), Torres focusses on “the tension between the representation and the abstract space.” She uses the horizon line as a foundation for the image. The effect of distance and displacement is enhanced in the scale of these long, thin surfaces. Torres’ figures look like colonial time travellers caught in fragile, sometimes fearful landscapes.

RealTime issue #57 Oct-Nov 2003 pg. 41

© Virginia Baxter; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Kate Stevens’ current paintings are energetic and evocative streetscapes. She takes photographs while walking: mundane, even dull, images tracing incidental everyday experiences of passing through streets or other urban pathways. She then re-photographs these snapshots using a digital video camera. The video can shift the framing of an image, or clip a detail, or return a virtual movement to the scene as the camera tracks across or zooms closer to the surface of the photograph. In this way the video produces something like a filmic sequence of images from a single photograph: often the source of the sets and series she produces. Stevens also frequently uses filters on the video camera lens to transform distance and distort colour relationships in the image. She rephotographs frames from the video screen, resulting in small prints that will be the reference and source for her paintings. Walk and photograph, video and photograph: the work of painting then begins. The lush, rich impasto surface and the high-toned colour of Stevens’ paintings are thus at a great distance from the impetuous gestures or fevered imaginings of the expressionist painters they might recall. They hold in the play of paint a trace of a photographic image and the play of paint is constrained by that image. In some, the blur and distortion is such that if the paint were not applied with a precise discipline, the image might disappear. It is important that this does not happen for it is through this process that the surfaces of her paintings enact or model movement and memory, remembering the experience of walking and looking–for the image to disappear would be to forget.

Kate Stevens graduated with Honours, Canberra School of Art 2001. She was awarded an ASOC Scholarship in 2002 to travel to Japan and an Emerging Artist residency at Canberra Contemporary Art Space 2003.

RealTime issue #57 Oct-Nov 2003 pg. 41

© Gordon Bull; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

The second Last Supper was one of the performance highlights of 2001, unruly and discursive, full of outrageous gags, wit, alcohol, songs and political barbs delivered by a team of experienced and new players. From the same company, Version 1.0, comes Questions to ask yourself in the face of others (Performance Space, May 30-Jun 8). It’s trim and taut, a 2-hander postmodern, post-apocalyptic parable as performed by Adam and Eve who happen to be performance artists and scouts in uniform. In a mix of deadpan declamation and neurotic outburst, David Williams and Beck Wilson play out the frayed couple’s return to the scene of the ‘original’ crime (a burnt-out bourgeois paradise) generating an increasingly loopy re-mythologising of their fate, counterpointed with a physical struggle that stops barely short of violence. They tell their audience, a jury of peers briefly back from the dead, “We were prepared, like good little scouts, but we weren’t ready enough…We performed poorly.” They are, it seems, seeking a verdict, “are we responsible for the world being fucked?” But is it absolution they’re after? “We may not be innocent, but we cannot stand to be guilty any longer.” A sometimes uneasy hybrid of script-driven schematism and rigorous physical performance, Questions to ask yourself… nonetheless hits home as conservative and right wing politicians continue to consign guilt and compassion to the rubbish bins of political correctness and history. In its rare outings, Version 1.0 is an important addition to the Sydney performance scene—we need to see more of them. Their next show, CMI (A Certain Maritime Incident), scheduled for March 2004 is now in development with Danielle Antaki, Nikki Heywood, Stephen Klinder, Christopher Ryan, Yana Taylor, David Williams and Beck Wilson in collaboration with Paul Dwyer, Samuel James, Simon Wise and members of Perth’s PVI collective.

RealTime issue #57 Oct-Nov 2003 pg. 41

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

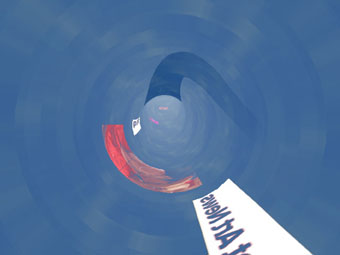

Tim Plaisted still from Surface Browser

A Rising Tide is a visual journey akin to racing down a winding narrow street at 120km per hour except that the street has become a graceful snake-like conduit that receives your queries as images and pastes them in fragments onto its inner skin. The transparent blue of this 3D space provides the participant with a distant view of the oncoming journey, which slides with myriad similes from the image bank of the internet. The speed and rush of the postmodern city and its pulsating ability to feed information through signs and symbols is a visual language analogous to the spatial environment created by the interactive elements of Brisbane artist Tim Plaisted’s new work.

A Rising Tide—An Internet Surface Browser attempts to provide a new ocular understanding of how search engines (such as Google) operate on the world wide web. In this application the user is confronted by a tube-like interface in which the web link or object query entered into the pathway becomes a page that moves across the surface of a pipe. The page acts as a kind of skin to a 3D object that dives and plummets through the pathways of the net. Loading images, the user navigates the links. Plaisted explains, “this is not a case of creating independent virtual 3D worlds but about re-mapping the existing visual aspect of the internet into an environment that can be entered and traversed. In this way, the solids representing pages can be seen as a way to give volume back to the millions of body images which make up so much of internet network traffic.” Plaisted’s Surface Browser seeks to provide a 3D visual experience of surfing the internet-a process that is otherwise formless or perhaps invisible to us as users.

Browser intervention is a recent exploration in new media art and one that Plaisted has entered from the perspective of visual social engagement. Much of his earlier work interrogated the simulated process of communicated reality. In 24hr Coverage TV news broadcasts appear as if pause is being repeatedly pressed–a newsreader emerges in a moment of repetitive distress with a barely audible stammer. The absence of content is highlighted yet we understand the image as a vehicle through which we are usually informed. Plaisted questions how decisions can be informed if they are “…made in terms of a society’s response to ‘the events of the day’ without full participation of the ‘public’ in an in-depth debate” (unpublished interview, 2001). For Plaisted, A Rising Tide is a valuable encounter. As a 3D visualisation of information it enables the user to understand, albeit in a somewhat abstract manner, how the web operates by indicating the journey of an enquiry.

RealTime issue #57 Oct-Nov 2003 pg. 42

© Zoe Butt; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

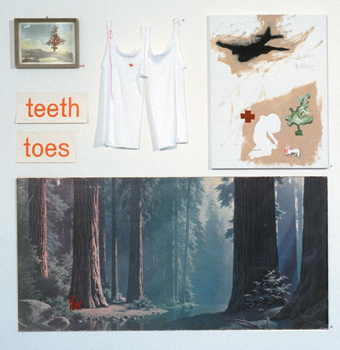

Heidi Lefebvre, installation view, 2003

photo Brenton McGeachie

Heidi Lefebvre, installation view, 2003

Joy and sadness. Giving shape to feeling. Heidi Lefebvre tackles things head on. Currently staging her first solo exhibition since graduating in 2002 with Honours from the National Institute of the Arts, School of Art in Canberra, she continues to engage with contemporary politics. Civilian Casualty at Canberra Contemporary Art Space, Manuka, in June, was the outcome of a NITA Emerging Artist Support Scheme (EASS) award, sponsored by CCAS. It represents a kind of ‘braving the world.’ Lefebvre knows now she is outside as she might put it, seeking opportunities, coming to terms with making art and making a living. Perhaps then the work speaks not only of these times, of itself, but of the positioning of the artist too, herself. Lefebvre’s exquisite works (a near sell-out) range across styles and media, from sketches and drawings to found jigsaw pieces, to bandages and blankets, to curious felt cutouts. The work evokes contrasting emotions; a sense of flight and trauma; comfort and shadows of grief; and as reviewer Russell Smith put it “a dream-like state where symbols of innocence contended with memories of pain or loss in the construction of a fragile sense of the self” (Muse Magazine, July 2003). A fitting start for any emerging artist.

RealTime issue #57 Oct-Nov 2003 pg. 42

© Francesca Rendle-Short; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

A recent arrival from Perth, and graduate of WAAPA, Paul Romano has been working consistently, alone and with others. He has just completed Stage One of a collaborative choreographic project, Transitions (with Simon Ellis, Anna Smith and Eleanor Jenkins), supported by Chunky Move as part of its Maximise Program assisting independent artists. Romano’s work indicates a sustained exploration into the possibilities of movement. He swings between 2 poles: fast, jointed movements, perhaps linked to a string of actions which travel across space; and still, very slow shifts which traverse a variety of bodily positions. His moments of stillness suggest an internal registration of corporeal feeling. He is in touch with his head and spine and their flexible possibilities, using these to construct movement pathways. I have the impression that Romano’s movement is composed of a series of positions that have been strung together to create a fluid whole or rather a series of shifts from one position to another. The result of such conjunction is that the pathways from one position to the next seem more focused on their endpoints than on the passage between them. What could be done to flesh out these pathways? Perhaps further variation in timing, quality and bodily tone/content would enrich them.

RealTime issue #57 Oct-Nov 2003 pg. 42

© Philipa Rothfield; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

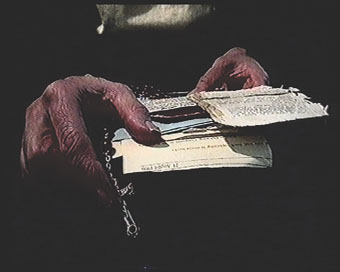

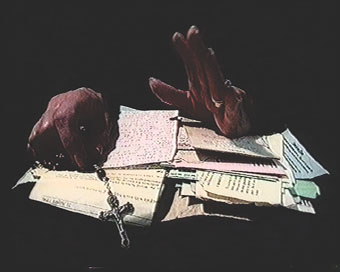

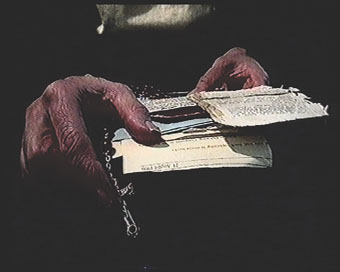

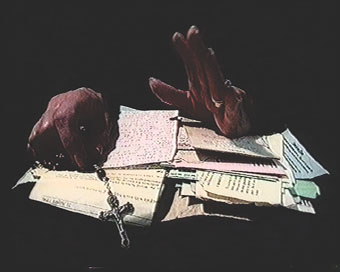

Kate Murphy, Prayers of a Mother, video still

Kate Murphy’s digital video Prayers of a Mother, 2001, featured in the remembrance + the moving image exhibition at the Australian Centre for the Moving Image in Melbourne (2003). Sydney-based Murphy graduated with honours from the Australian National University in 1999 and has been resident artist at the Canberra Contemporary Art Space and the Canberra School of Art. Fiona Tripp writes in the remembrance catalogue, “Central to Prayers of a Mother is the voice of Anne Murphy, mother to artist Kate and her 7 siblings. With great emotion, she describes the prayers she makes daily for her children and immediate family, expressing her hopes for their health and happiness, and specifically her passionate desire that they will all return to the Catholic faith. The mother occupies the central screen of the 5-screen installation, but rather than her face we see a close-up of her hands holding her prayer book and rosary, her gestures echoing the longing in her voice. On either side of this screen are 2 projections which show the children’s faces as they listen.” Prayers… is regarded by many as one of the most powerful video installation creations of recent times. Compared with the works of Viola et al, it is brief at 15 minutes but its potency is concentrated and the durably memorable. Murphy’s next work is eagerly awaited.

RealTime issue #57 Oct-Nov 2003 pg. 42

© RealTime ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Ingrid Voorendt, Naida Chinner, Helen Omand and Astrid Pill are all making a significant impact on the South Australian dance and performance scene.