Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

A lot of experimental sound happening in Sydney at present is appearing in somewhat unexpected locations. Sonic Alchemy, a series of afternoon performances, was held at the Brett Whiteley Studio in Surry Hills, set in front of Whiteley’s painting, Alchemy.

Experimental sound and music has long been associated with gallery spaces. The art world has often been more accepting of new and difficult sounds than the music world, especially in the name of art. However, in this case, the surreal imagery and explicit actions of Whiteley’s monstrous work, to my mind, are not at all in keeping with the improvised, minimal, experimental audio presented here.

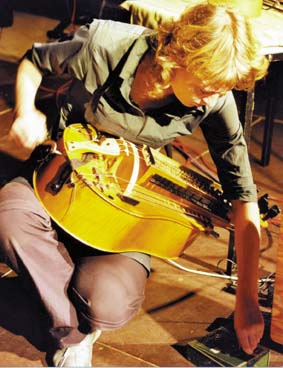

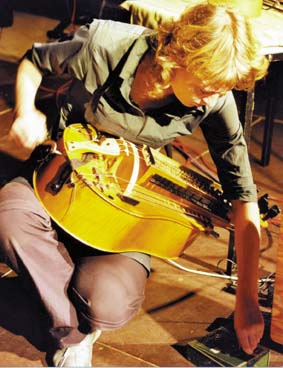

The series of improvised trios has been curated by local musician Jim Denley, and includes a number of improvisers currently active in the Sydney new music and audio scene. For this afternoon’s performance the 3 musicians are set up without PA, each with his own amplification via guitar amps and a shabby home stereo.

Oren Ambarchi is the best known of new musicians to emerge from Sydney. He is a sought-after performer on the international scene, and is also very active locally. Using a heavily modified guitar and an array of guitar pedals, he pulls audio that has little causal connection to his instrument and actions. Less well known are Peter Blamey and Brendan Walls. Like Ambarchi, they use a series of feedback techniques to draw sounds from their analogue technologies. In both cases, this is centred simply around a mixing desk which has been ‘improperly’ patched and so draws different types of feedback. These sounds are often high pitched, extremely stripped back and minimal: sinewaves, squarewaves and the odd standingwave for good luck. Though not loud, these frequencies can be disturbing to the uninitiated. Casual visitors to the gallery quickly press fingers firmly into their ears.

The performance began quietly and minimally, the tones and frequencies in the high range making use of the reverberant space of the gallery, and ranged into a more fully textured and disjunctive style as the musicians let their individual voices play out. The key moment came near the end when a slow burning drone was initiated, the sound gradually building in volume and density. With no PA or sound engineer, the performers were free to take this to the limits—a wild card in this environment. Just as the volume reached the limit for many in the audience, Ambarchi created an extremely rich and dense audio. A slow fade to the end seemed inevitable but this was dramatically subverted by Blamey who continued playing after Ambarchi and Walls had clearly finished. Improv is usually about the group.

As with much new audio, the space plays an extremely important role in determining the outcomes. The variation this space creates is well worth experimenting with, and what better way to spend a Sunday afternoon than in an unfamiliar environment with new and improvised music.

Sonic Alchemy, curated by Jim Denley, artists Peter Blamey, Brendan Walls, Oren Ambarchi, AGNSW’s Brett Whiteley Studio, Surry Hills, Sydney, April 21

RealTime issue #49 June-July 2002 pg. 35

© Caleb K; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

I’m off to the Judy for my first experience of Elision. I’d heard about them, I’d heard they were real quality, and I’d heard they were mainstream modernity—the classical avant-garde of the conservatorium. It was all true. The program drew on material from the last decade or two. Most pieces were by composers involved collaboratively with Elision.

The program opened with a solo percussion piece written by Richard Barrett and played on the vibraphone by Peter Neville. The performance was a stunner. He’s playing chords with a couple of mallets in each hand (a bit like playing golf with 4 clubs and 4 balls at once), and the piece must have thousands of notes—all sorts of chords, and it’s really fast. I’d love to see this guy working the chopsticks at a Yum-Cha. Neville made a couple of early mistakes (whoops—missed), but this is a failure rate any machine would envy. It’s easy to get used to the enormous polish that excellent performers have.

Two duets by Michael Finnissy for guitar and voice followed, with Geoffrey Morris on guitar and Deborah Kaiser singing. Great voice, especially low. Lots of medieval-style ornament. The guitar was a bit soft in the first piece, but came into its own in the second. This was followed by a solo piece written by Aldo Clementi. Morris’s guitar was assured, but the piece itself was a little incoherent for me. There’s that whole old school avant-garde thing—which of these two random sequences do you prefer? It’s an approach to composition that runs through the entire concert program. From an information/theoretic point of view, there’s a lot of information in random sequences. From a musical point of view, there’s none.

The first half of the program then finished with a bravura solo performance of a Richard Barrett trombone piece by Ben Marks. Once again the performance was gob-smacking. However, as a compositional strategy I can’t help but think that ‘new sounds for old instruments’ lost its cachet about 20 or 30 years ago.

After the break was the highlight of the concert, Timothy O’Dwyer performing his composition, Sige, for solo bass sax and prerecorded backing. The piece begins with O’Dwyer centre stage—rocker hair and Pelaco shirt—carrying a bass saxophone. Underneath, a low sustained drone changes up a fourth like a sluggish 12-bar blues is about to roll forth. Instead, the drone continues as O’Dwyer fumbles about with the sax, a few fitful noises, classic ‘just can’t get into it’ stops and starts. The drone stops for a brief moment and the process repeats. But with each repeat, O’Dwyer starts to play more, until we’re watching and hearing wild, Jimi Hendrix-meets-Mac-truck multiphonics, trills, grunts and squawks. It’s the archetypal sax solo. And he does this again and again and again. The playing is phenomenal, but it’s totally hermetic, the performer isolated in his own ecstatic space like a caged rat pressing the food bar over and over again, raising the question: Who’s a solo for?

Empire of Sound, Elision ensemble, The Judith Wright Centre of Contemporary Arts, Brisbane, March 24

RealTime issue #49 June-July 2002 pg. 35

© Greg Hooper; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Gideon Obarzanek

It’s been 7 years since the formation of Chunky Move, with 4 of those as Victoria’s state dance company, and Gideon Obarzanek is the first to admit that developing his craft in the public eye—and with the burden of associated expectation—has been challenging. This year, a move to a new studio with expanded facilities has helped stabilise the company’s local connections with open classes for professionals and

Maximise, a program offering space and promotional support for independent practitioners. After polling the public about their tastes in contemporary dance, Chunky Move are presenting the results in Wanted, a double-bill featuring Clear Pale Skin and Australia’s Most Wanted: Ballet for a contemporary democracy. Later this year, the company is touring to Sydney with the multi-media installation Closer, before heading off to Budapest and France.

Commissioned earlier this year to create a piece for Graz Opera Ballet in Austria, Obarzanek took the opportunity to meet up with European choreographers including Alain Plaitel and Wim Vandekeybus.

GO: Graz Opera Ballet was my first commission in 3 and a half years, and was both exciting and scary. After 3 years hard work in Melbourne, it seemed important to work with other people again. I was very happy with the work I did—it was an early version of Clear Pale Skin, and I came back and reworked it with my dancers. It’s good to travel but I have changed and need to work much more intensively, and with dancers who know the way I work. I don’t think you advance very far as a freelancer. But I did come back with enthusiasm and a lot more confidence, wanting to do more and do it better.

How did Wanted fit in with the work you have been doing lately?

In previous works [like Arcade], I have had an interest in the relationship with the audience. Then I came across a book by 2 Russian visual artists, Vitaly Komar and Alexander Melamid, who in 1993 conducted a survey to find out the ‘most wanted’ painting. I thought the discussions in the book were really compelling in regard to how a vision could be arrived at through the mechanism of a democratic process. Then we had the federal election last year, which I found simply demoralising—the 2 major parties were following the polls very closely and not taking responsibility for important decision-making. I remembered this book, and thought it would be interesting to make a dance piece about how a work could come together from the results of what people most wanted to see. The work of Komar and Melamid arrived at a style of painting from a period that most suited the answers—a Romantic landscape from the 19th century. While my work does arrive at the ‘most wanted’ work, the piece is close to an hour and is mostly concerned with the report itself and an analysis of the result—it’s actually performed to a reading of the report. So in a sense it’s a documentary, and not about dance but (a report which is) read through dance.

This, being a novelty or ‘gimmick’, is quite different to how you normally structure your pieces.

It’s very different. The report directs the work, and it’s split into sub-sections such as choreographic structures and qualities of movement, music, costumes and sets. So it’s like a series of small chapters, and there is a process of reducing each element down to the highest preference and then adding all the elements together at the end. What was difficult was not to impose my own idiosyncrasies on the work. It really became group-choreographed through a series of tasks I set, so I didn’t have much input into the actual movements or expressions.

It is interesting that you’ve arrived at this project given Chunky Move’s agenda to open up contemporary dance to new audiences—the idea of polling is almost the logical conclusion to that.

And that definitely began with Arcade’s format, a series of 6 choreographers and directors in 6 shops, with the works going on simultaneously. The audience could make a decision about what they did/didn’t want to see and how long they would stay with works—which also made the works somewhat competitive. As an artist running a major, state-funded dance company, you are very exposed to discussions about performing arts on a federal and state level. It seems in Australia, particularly since the Nugent Report, many of our conversations about art have been about who makes it, how much it costs, is it getting to the right people, and is it what people really want. This work is a response to the language, time and emphasis that is placed on the economics of art. And it’s certainly not an answer but probably another question. It’s an extreme response, but it came quite naturally.

You are constantly driven to make work that’s relevant to a large audience. What other things do you draw from? Last time I spoke to you, you mentioned film, music and cartoons.

I’ve always had a curious nature. When I was younger people thought I was too distracted from being a dancer, whereas now it’s an advantage in regard to making work. But I must say I feel a bit less connected to pop culture—particularly TV. I think I made signature works earlier on—things that came naturally to me about how I was placed in the world. But I don’t want to tell those stories anymore, and I’ve become more interested in the medium itself. So my works have become a little more analytical; they’re not story or character-based but about the relations between performance and people.

Regarding the themes of Clear Pale Skin, I recalled a conversation we had about the horrors of ballet school—is your past revisiting you in this work?

The whole ballet environment is a strong influence in this piece. It revolves around an obsession that one woman has with another, believing this other woman is extraordinarily perfect and that she herself is not. These kinds of distortions are certainly drawn from my experience at a suburban ballet school and then the Australian Ballet School in Melbourne. Seeing how obsessive and fanatical dancers can be about their training, the perceptions of themselves and the people around them, and the competitive nature of it all. So in this work there is a lot of faux ballet going on which is used to set up the relationship between these 2 women.

Did it ever become a problem having these dancers who are quite perfect and the piece becoming self-referential?

No, not really. Luckily most of my cast, and particularly Fiona Cameron, take an interest in the idea of the grossly imperfect and work on all their insecurities, letting them fester and come forth. You certainly don’t get the impression they are perfect when they do that. And the piece is not really talking about imperfect people but their perceptions of themselves, so the dancers can be quite amazing and beautiful.

The company has this great new studio—how has that changed things?

We started here 7 weeks ago when it was still a hard hat area. This building houses Chunky Move, Australia’s Centre for Contemporary Arts [ACCA] and Playbox’s set-building workshop. We have 2 studios where previously we had one. Previously too, the conditions of rental from the Opera meant that if they had rehearsals they could kick us out. One of the studios is enormous, like an aircraft carrier, and the other is much smaller. We are clocking a lot of hours because we can stay here all night. It’s great to have a home. We’ve also noticed that our morning classes, which are open to professionals, have increased in attendance and this year we’re going to have a lot more showings. Lucy Guerin is showing her work here later in the year, which will be the first time the studios will be used for a season. And we have a program called Maximise where choreographers can have studio space, technical equipment and some marketing for independent projects. We do have these resources and we like to share them when we can.

Working in other media—film, CD-ROM, installation—is an interest of yours. What have you got coming up in the future?

I have an installation with Peter Hennessy, Darrin Verhagen and Cordelia Beresford called Closer. It’s a projection in a room, the opposite wall of which is padded with sensors. People coming in are encouraged to ram their bodies into the wall, which effects the film. It’s not cryptic either—people learn very quickly which part of the wall effects which part of the film so it becomes a tool, a game.

We shot it on film but it actually uses video because all the information sits on a hard drive—but it does have a very rich filmic look. It focuses on a body and it is shot in close-up and extreme close-up. Working in a live context you assume that the body is viewed from head to toe, even in a small venue. The one thing that film or video has to offer, and which I like as a choreographer, is the close-up. Working with dancers in a studio you see a lot of interesting detail which disappears when you put it on stage—like tendons under the skin, and hand grips. One of the reasons I’m so attracted to the installation is the relation it has to moving bodies in the room, and the choreography emerging as people move around and ram the wall and make teams—that live aspect interests me most. Closer was commissioned by the Australian Centre for the Moving Image [ACMI] for its new building in Federation Square, but it’s not going to be open in time so we’re previewing it in antistatic at Performance Space in late September.

See Jonathan Marshall’s review of Wanted.

–

RealTime issue #49 June-July 2002 pg. 37

© Erin Brannigan; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

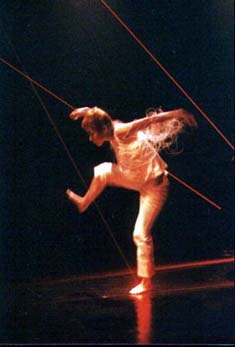

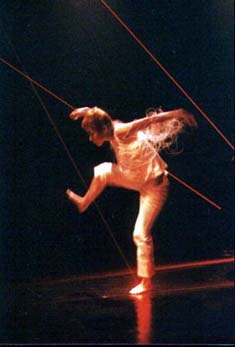

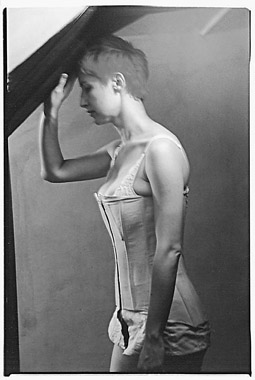

Julie-Anne Long, MissXL

photo Heidrun Löhr

Julie-Anne Long, MissXL

An orange light flashes in a corner of the Seymour Centre forecourt. A tinny recording of a familiar tune bounces off the walls. Suddenly a Mr Whippy ice-cream van emerges, appearing at first larger than it is. A bemused looking, genuine Mr Whippy drives. In the passenger seat is Julie Anne-Long in messy orange wig, her head moving left to right on a horizontal plane while her forearm, propped up on the window sill, moves up and down. Both gestures are precisely coordinated, surreally slow motion. As the van slides by, a grotesquely grinning Mrs Whippy is captured almost in freeze frame.

Mrs Whippy is one of 3 pieces in a dance-performance programme presented by One Extra Dance featuring MissXL, the performance persona adopted by Long whose body and spirit refuse to conform to balletic (or even postmodern dance) ideals. She is not the dutiful dancing daughter but a wayward woman conceptualising, choreographing and performing a contemporary and hybrid form of burlesque. In Mrs Whippy, MissXL “calls on her prestidigitatorial and pantomimic powers to expose a mother’s fears”; in Cleavage she “holds you to her bosom in a socio-erotic danse macabre”; and in Leisure Mistress she “discovers terpsichorean heights in a dancer’s demise” (program notes).

After introducing the audience to the delights of Giuseppe’s ice cream, Mrs Whippy transforms into stereotypically evil characters from children’s literature. With a long black beard she dances in front of the iron gates of the forecourt, hopping from one leg to another, one arm moving up as the other goes down, the rhythm awkward, hands balled into fists. Long skillfully manages the large open space as she moves through the audience on her way to each new performance place. At one point the audience is ushered into a triangular nook where we watch through a large window as she dances on a box wearing a long, crooked nose. Long’s final dance as Mrs Whippy is one of stillness. She stands on a box lit by the ice-cream van as moving images are projected onto her apron. Robert Helpman in Chitty Chitty Bang Bang entices 2 children into a playhouse on the back of a horse and cart. As the children move inside the house the exterior falls away to reveal the bars of a cage. At this point Long howls in pain, her body slumping forward as she clutches her apron in a fit of maternal anxiety.

Cleavage is performed in the Downstairs Theatre. The set is triangular with the base running across the front of the stage and the apex receding into a vanishing point at the far end. Stage left sits a reel to reel recorder. The recorded voice of a male paleontologist recites information on geological formations and rock cleavage. Long appears stage right, chatting informally with the audience while dressing in a brightly coloured bustier and performing dramatically exaggerated gestures of grooming. The reel to reel recorder plays throughout Cleavage incorporating a number of different voices—a young female change room attendant tells stories about fitting women with brassieres. Male voices discussing the look and feel of breasts are juxtaposed with those of women. Children’s voices delineate similarities between breasts and buttocks while a young boy asserts that he always draws pictures of women with cleavage! A dance theorist pontificates on the invisibility of breasts in dance. Babies suckle. Long skillfully interacts with these voices as the stories cue segments of her live performance. Cleavage is a consummate work. The recorded stories complement an intelligent and witty live text. Long’s versatile dance performance melds dramatic and performative elements. Cleavage replaces the brooding malevolence of Mrs Whippy, where the boundaries between good and evil merge, with an up front and often hilarious piece of dance-theatre about fleshy bits.

Long’s world-weary Leisure Mistress, modeled in part on Marlene Dietrich in her later performing life, is wheeled into the performance space by a faithful assistant (Victoria Spence). Dressed in blue chiffon with oversized faux diamond rings dripping off her fingers, the Leisure Mistress repeatedly tucks a wayward section of blonde bob behind her ear. Her first dance (she announces each numerically) is performed lying on her back. Only her hands and feet move in repetitive phrases in time with a perky musical track. The other dances are similarly compressed variations of the Diva’s once famous dance pieces now performed in absurdly reduced form. One dance is performed leaning against the side of the stage. As her legs continually collapse under her, the Leisure Mistress runs her hands down her thighs to re-straighten them. This correctional gesture becomes a key movement phrase in her dance of extremities. In the final dance (“the first she ever performed”) the Leisure Mistress undertakes a costume change which proves disastrous. In a hair net and an undersized dress which gapes at the zipper, she cavorts about the stage performing derivative contemporary dance movements in an attempt to remain relevant to her audience (having described herself as a “submerging artist” in the age of the emerging artist). Somehow this final image captures what Julie-Anne Long is so good at conjuring and performing in dance: the weird and wonderful world of the grotesque and the anxieties that form it.

Miss XL; concept, choreographer, performer, writer Julie-Anne Long; designer Rohan Wilson; music (for Mrs Whippy) Sarah de Jong; video Samuel James; dramaturg/co-writer Virginia Baxter; lighting Janine Peacock; One Extra Dance, Seymour Centre, April 3-13

RealTime issue #49 June-July 2002 pg. 38

© Kerrie Schaefer; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Questions of space and time often arise in Shelley Lasica’s work. Space has been highlighted in a number of her Behaviour Series, with work being presented in very small rooms, in large auditoriums, in hallways, and in galleries. In those works, the viewer was often and variously made aware of the ways in which his/her body was implicated in the viewing relationship.

History Situation, like Situation Live (1999), presents issues in a sedimented manner. Its themes appear to be trapped beneath that which occurs on the surface. For example, there is a sense of narrative in both works. Dancers combine, interact and separate. There is almost a story to their actions but the nature of the story is never made clear. Rather it is treated performatively and according to kinaesthetic relationships.

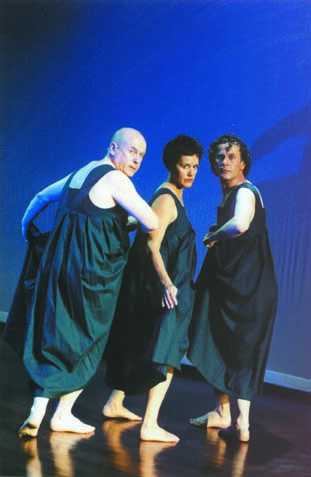

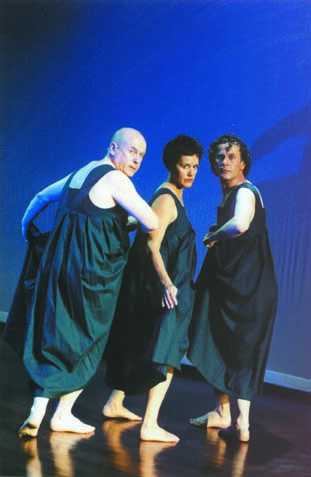

Five dancers enter the newly refurbished Horti Hall, all in turquoise. Each takes off his/her cloak and rests it on the warm wooden floor. The space is wider than it is deep. A large translucent rectangle lies on a tilt at the back, lit in reddish brown. Two monitors show a series of images by Ben Speth. These are sparse public spaces; phone booths, atriums, streetscapes, banks—locations populated not by people but reminiscent of them. The locations may be deserted but their content suggests a virtual habitat within which human movement may be found, movement such as occurs outside the monitors.

The dancers are connected. They enter together and leave together. They wear the same colour and material, folded and pleated to suggest a degree of individuality but clearly they are of similar ilk. A delicate piano arises; the staccato rhythms of Jo Lloyd’s movement offers another music. The 5 form a number of beautiful tableaux—5 green bottles, all in a row. Not all the movement is elegant, dancerly; some of it is gestural, occasionally naturalistic. Jacob Lehrer and Jo Lloyd perform and repeat a duet. Deanne Butterworth and Bronwyn Ritchie move their hips in synch. The group gathers then disperses. Repetition, recognition.

The look of the Other plays its part in these comings and goings—bearing witness, signifying relationships. There is conflict, and opposition; referring perhaps to events within what is called the Source Script by Robyn McKenzie. The dynamics of 5,4,3,2 and 1 are quite complex in all their combinations, especially as there is a sense that each configuration means something particular, something that cannot simply be transferred from one body to another. And yet, the emergence of one body, one lived corporeality in all these dancers, is palpable. Although Lasica doesn’t perform here, her body is evident in the bodies of the dancers, an absent presence.

Francois Tetaz’ music assisted the sense of connection and buried narrative within and throughout the piece. Its ending was evocative, e-motional, allowing for personal speculation and imaginary dialogue. If this work was about time, the final moments of music and movement suggested a metaphysics of time, of lived time, human (inter)action, finite and focused. The dancers collect their cloaks and leave the space. Time is no more.

History Situation, choreographed and directed by Shelley Lasica; dancers Deanne Butterworth, Tim Harvey, Jacob Lehrer, Jo Lloyd, Bronwyn Ritchie; music Francois Tetaz; set and lighting Roger Wood; costumes Richard Neylon; source script Robyn McKenzie; images Ben Speth, Horti Hall, Melbourne, March 14-24.

RealTime issue #49 June-July 2002 pg. 38

© Philipa Rothfield; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Here. The place in which you find yourself. From the viewing level, the rear stairs of the Turbine Hall drop though 2 tiers like a medieval descent into purgatory and hell. Brian Lucas begins his story eye to eye with his audience, a story of victim/aggressor drawing on the impulses of serial killer Jeffrey Dahmer and lures us from safety into less certain waters.

Voice and movement embody his text, a recollection of events one cold New Zealand night. Our gaze travels down through this torch-lit temple to an intimate space—a dining table, a serve of raw liver, a romantic dinner date. The symbiosis of word and gesture set against Brett Collery’s aural backdrop of a girl pop group, returns us to another version of events. Repetition lulls, then puts us on alert. Danger intensifies, and Lucas disappears below as into the mouth of hell. Calmly, he re-emerges from the basement—as though oblivious to the ravaging animal that had just given vent to its most depraved desires.

Here/There/Then/Now, an initiative of director Cheryl Stock, brings together independent solo dance artists and their collaborators (visual, multi-media, lighting and sound designers). Four unique sites around the Brisbane Powerhouse were nominated for the creative response of 3 discrete creative teams who came together under Stock’s direction in the fourth space, the Visy Theatre, for Now.

There. We follow our guide and peer down into a concrete cell resonating with Nok Thumrongsat’s plaintive Thai singing. Choreographer Leanne Ringelstein relentlessly assailing the walls of their confinement. Trapped, neither acted upon the space in the way Lucas did, but instead made themselves subordinate to it, responding within the language range of their respective disciplines. Purporting to examine cultural responses to stress and confinement, There ended with its first action—the assertion of one individual against an/other, unfortunately leaving off just when it got interesting.

Then. Time past. Embodied in still life, a painting in 3D: Vanessa Mafe and Jondi Keane’s response to the theatre foyer site. Still life? And yet the dancer moves, exploring the installation—an arrangement of stoneware on a suspended glass table. Picking up, putting down, rolling around an orange. Ko-Pei Lin looked lovely in her orange-lined hoop petticoat, lovely in Ian Hutson’s stills that line the walls. So…why is she moving? Then might have worked just as well in a conventional black box for the dance added no new meaning, attempted no journey, held no dialogue with the place Ko-Pei Lin was in.

Beyond its visual design, Then was an aesthetic frolic within the language of contemporary dance as accumulated in the performative body of Ko-Pei Lin. (A smattering of oriental hand movements slightly enriched the vocabulary.) For director Stock, an aspect of the project was the way in which the body’s accumulated history of technique and culture inform creative outcomes. The exclusive physicality of these dancers’ histories sometimes seemed to remove them from the immediacy of the present. Ringelstein’s voicelessness in There seemed an unnatural gag on her expressive potential, where singer Thumrongsat moved with a natural fluidity (holistically) across the borders of discipline. Thumrongsat was actor/singer/dancer, her performative body providing sound, gesture and meaning.

Now. Where we culminate, where we converge. Stock speaks of the “site as a sparsely fragmented repository of what has gone before”, and of “stairs to nowhere, deep crevices with no purpose.” If the site began as a void of ambiguous negation, Now did little to fill it. Juxtapositions that are merely serendipitous can’t be relied on to engender new narratives. Floating objects—hoop skirt, finger cymbals, a candle—referenced the previous works as part of a sea of memory: amorphous and impact-free. Three discrete themes, woven together in time and space, never bore upon each other to produce a fourth element.

After a while though, a tableaux evolves. Girl eats orange, transforming still life. A story is retold, transforming the past. Finally, a step forward, into the unknown, into future stories. The re-action becomes action; relationships move beyond design and sensation and begin to initiate meanings for the spectator, allowing us to become active listener, not just voyeur.

Lucas’ creative response was both active and reactive. If the site was point A, his Dahmer text gave him point B, between which a productive tension took place. This tension forced him to apply conceptual (rather than corporeal) agility in order to command the given space to serve a greater purpose. After Lucas’ layered and multi-disciplined opening, what seemed lacking elsewhere in the program was an explicit intellectual response, an equivalent engagement with a resource of ideas. Here was where I wanted them all to be.

Here/There/Then/Now, director Cheryl Stock; choreographers Brian Lucas, Leanne Ringelstein, Vanessa Mafe, Cheryl Stock; dancers; Ko-Pei Lin, Leanne Ringelstein; singer Nok Thumrongsat; composer Stephen Stanfield; sound artist Brett Collery; visual artists Jondi Keane, Ian Hutson; lighting design Jason Organ, Brisbane Powerhouse, May 15-18

RealTime issue #49 June-July 2002 pg. 39

© Indija Mahjoeddin; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

The Age of Unbeauty, ADT

At a time when opportunities to experience seasons of contemporary dance works are thin on the ground in Sydney, events like the forthcoming The Action Pack season at The Studio at Sydney Opera House (June-July) and antistatic at Performance Space (September-October) are welcome indeed—as is the news that Robyn Archer’s 2003 Melbourne Festival will have a dance focus. Given the demise of the national touring organisation Made to Move, these days it seems easier for choreographer Phillip Adams to get to Mongolia (as he did courtesy of Asialink in 2000) than to Sydney (although this trip is with the last of Made to Move’s funding). The chance to see 3 companies of such high calibre as Adelaide’s Australian Dance Theatre, Melbourne’s BalletLab and Kate Champion’s Force Majeure performing in a mini festival is exciting enough. This, plus the offer of generous discounts (“a strictly limited offer” of $69 for all 3 shows), is almost too good to be true.

The Studio publicists have gone all out promoting the threesome as “fast, fraught with risk, breathtaking, the equivalent of white water rafting” and my favourite, “sex on legs.” Thankfully, they’ve also found a few column centimetres for the smarts, ie for “fresh” read radical approaches to dance and for “thought provoking” read personal, political and sociological. There’s even a warning about “adult themes.”

The last time we saw Phillip Adams’ Ballet Lab in Sydney was in the remarkable Amplification which, like a lot of Australian contemporary dance works, has made successful international appearances. The company’s new work, Upholster, is part installation, part deconstructed movement, part furniture workshop with live sound mixes by turntable master Lynton Carr. RealTime’s Philipa Rothfield has described Upholster as “intricate and detailed, manifesting Adams’ deep-seated interest in design. Hinting at the conceptual grounds of upholstery, it weaves an aesthetic web. On the surface, beneath the surface, questions are covered over, but they are there to be discerned as the work unfolds.” (RealTime#43, p33).

Sydney audiences went wild for ADT’s Birdbrain (RealTime 44. p37) which toured here last year with its witty and sometimes unbelievably vigorous dance vocabulary. This time they’re bringing their new work, The Age of Unbeauty, which premiered as a work-in-progress at this year’s Adelaide Fringe. Once again choreographed by ADT’s artistic director Garry Stewart, with sound design by Luke Smiles and video by David Evans, this is a developing work. Conceived at a time when world politics were making their own risky moves, Stewart describes the dark poetry of The Age of Unbeauty as “a highly personal response to the terror in man’s ability to act inhumanely…”

Once the word was out, it was impossible to get a ticket to Kate Champion’s Same, same But Different which premiered at this year’s Sydney Festival. Breaking new ground in the live/filmed dance genre, Same, same like all the works in The Action Pack season, showcases the work of some truly remarkable Australian dancers (RealTime #47, p6). And across the 3 works, you’ll also see a star lineup of collaborating artists—among them, filmmaker Brigid Kitchin, designers Geoff Cobham, Dorotka Sapinska, Gaelle Mellis, Damien Cooper and composer Max Lyandvert.

Take note. These shows are the goods. Go see.

–

The Action Pack: The Age of Unbeauty, Australian Dance Theatre, June 25-July 6; Upholster, BalletLab, June 26-6; Same, same But Different, Kate Champion & Force Majeure; The Studio, Sydney Opera House. Bookings 02 9250 7777. www.sydneyoperahouse.com Forum: Champion, Stewart, Adams, The Studio, June 29, 5pm.

RealTime issue #49 June-July 2002 pg. 39

© Virginia Baxter; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Having only just returned from Melbourne after 11 days of working with young writers on responding to an exhausting, exhilarating and innovative 2002 Next Wave, and having walked straight into helping get RealTime 49 to the printer and onto the streets, there’s been little time to think about an editorial. So this will be brief.

One of the saddest things about Australia’s refugee crisis is the widespread lack of empathy for those seeking a haven from war and persecution. This amounts to a major, in fact a national, failure of imagination. How rare it is to hear questions asked about what it would be like to be a refugee, how you would handle it emotionally, who you would turn to for help and, yes, what it would mean financially.

However, there are a growing number of artists who are addressing the issues, answering these questions through their art, direct protest and some quirky activism. Bec Dean’s “The artist and the refugee” describes the political fictions by which refugees are trapped (not just in mandatory detention centres), the many ways artists are trying to undo them and where you can turn to participate. Kerrie Schaeffer reports on a Newcastle youth performance written by an Iraqui-Australian about the refugee experience. In Melbourne I saw Platform 27 & Melbourne Workers Theatre’s The Waiting Room, a gruelling recreation of life in a detention centre.

The second notable failure of imagination comes from the Cultural Ministers Council in the form of The Report to Ministers on an Examination of the Small-To-Medium Performing Arts Sector. The document produces a classic double bind. Yes, the sector is the key innovator in performance and it is in financial surplus (kind of). But, yes, the sector is experiencing a serious diminution of its capacity to innovate for want of funds, artist burnout etc. The solution? Nothing much. Everything (business planning, clearer government expectations, inter-government cooperation etc) but funds. Like the visual arts (also subject to an enquiry already signalling no new funds), the small-to-medium performing arts sector desperately needs additional, ongoing funds and the suggested reforms to government communication. It’s not just that the sector is disappointed by the lack of funds at the end of this particular rainbow, the word was out about that a while back, but it is shaken by the shoddy analysis and the perpetuation, in fact, of the double bind which applauds the work and keeps it in firmly and exploitatively in check. KG

RealTime issue #49 June-July 2002 pg. 3

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Caca Courage

Disability, disability culture, and identity politics were just some of the themes and issues celebrated with passion and debated with rigour at the High Beam Festival. This festival offers a rich, colourful and at times, cutting edge program of theatre, music, film, dance and visual arts exploring the theme of disability. High Beam is not concerned with its marginalised status in the broader ‘arts as excellence’ arena, nor the spare seats and low profit outcomes. Its purpose is making the arts accessible to a group often excluded both from the arts and from the means of producing art. The ‘art as therapy’ model, or ‘medical model’ as some people call it, seems no longer acceptable as the modus operandi. While High Beam makes room for such art, its motivation is more closely aligned with a cultural development model that aims for an enriched and inclusive society where disability is not about being on the wrong side of ‘normal’ (as the medical model would have it). On the contrary, ‘coming out’ takes on a whole new meaning both within the festival productions and on the streets.

As other minority groups have staked an identity out of oppressive regimes of otherness, people with disabilities are making visible their bodies, identities, ideologies and sexualities, weaving personal narrative into works of theatre, comedy, dance and visual art and evoking new representations that challenge constructions of normalcy.

Caca Courage, presented by Access Arts and Queensland Performing Arts Centre, entertains, provokes and challenges the boundaries of ‘normality’. “Caca” is the French word for ‘poo poo’, and this work metaphorically ‘shits’ on the patronising idea that people with disabilities are so, so, courageous. This is achieved through a visually stunning production and a clever series of provocative moves that defamiliarises, in the Brechtian style of ‘alienation’, the ideologies of the ‘normal’ body.

Mat Fraser’s Sealboy: Freak moves beyond the personal narrative and juxtaposes 2 characters, one representing the historical genre of human freak show exhibits, and the other a contemporary actor with a disability struggling to eke out a career in the mainstream. Fraser uses the ‘spectacle’ of his body, at the same time as reclaiming the word ‘Freak’ in a deliberate attempt, in his words, “to shock people out of their complacency.” Fraser wonders whether he is in fact only read as a ‘freak that acts’, and not as a talented professional actor. Fraser worries that too often the audience responds with the ‘wow factor’ such as, ‘it’s incredible, what, with him having short arms and everything.’ Fraser’s show is a piece of realism yet he plays with notions of identity via postmodern pastiche, providing both entertainment and witty retort to straight culture through Rap-style music.

Most of It’s Queer is by Philip Patston from New Zealand, who describes himself as a gay disabled vegetarian, and who relates through comedy and in a very conversational style the everydayness of his cerebral palsy and life as an actor in a New Zealand soapie. Patston’s character and mannerisms add a charming quality to his stage presence. His contemplative, playful and yet often covertly serious material was well received by the audience. Patston claims, however, that he never goes on stage with the intent to educate people. “I’ve done that” he says “and an audience just sees right through it and goes, oh we’re being lectured at. So my work is to entertain but it comes through my life and my training as a social worker—that’s what makes it work—I’m taking the piss out of society.”

Aside from the performances—and perhaps more evocative—were the forums, workshops and post-show outings in which performers and artists came together to share conversation over food and wine. Often what goes missing in the reviewing of a production are these everyday spaces and unfolding of ideas. One may well imagine that in the difference of disability lies homogeneity, shared experiences and unifying ideologies. While on some level there is a sense of disability culture, many came to agree that indeed the word ‘culture’ could well be replaced with ‘culture(s)’ to reflect the real and surprising diversity amidst those who identify as people with disabilities. Debate raged over disability politics and the role of the arts. Some argued for the drawing of distinctions between ‘professional performance art’ and that which is described and experienced as ‘therapy.’ Whatever decisions are made for the next High Beam Festival, we can be guaranteed of a radical exposure to culture(s) of disability.

Sealboy: Freak, Mat Fraser; Most of It’s Queer, Philip Patston; Caca Courage, Access Arts & Queensland Performing Arts, High Beam Festival, Adelaide, May 3-12

RealTime issue #49 June-July 2002 pg. web

For Part 1 of this interview: “Rosalind Crisp: a European future”,

For me the choreography is a vehicle that I use in performance…I feel like I’m more interested in using the material—going past the dancing, supported by technical foundations that I can move off from. I’m not concerned so much with being a good dancer—I’ve become interested in something on the other side of the dancing.

Could this be a difference in your sense of ownership of the material?

That is an issue—being the choreographer definitely effects the relationship. I can do what I want with it in a way. However, the material I’ve made with them has definitely come out of the dancers’ bodies too. The solos in traffic were worked out with them, were made on and with them. So the material itself is material that they do best. I think they ‘own it’ really well. We recently performed traffic in Melbourne at Bodyworks and that was one of the comments—that Katy and Nalina were right ‘in’ the movement.

There’s something else?

Well it is what I’m interested in. I’m not sure that I am getting to the other side or going past doing the choreography well. Perhaps it’s a kind of different maturity…The dancers are concerned with looking good and that’s one of the things that makes them dance well, but I’m not concerned with that anymore. I think I probably was once. Now I simply use the material and the body I’ve got.

There’s always been a strong sense of performance when you dance—a presence and impression of spontaneity.

Years ago when I was doing more improvisation I think I probably did rely on my performance to pull it off, which may have developed a particular strength. But I’ve realised I really like working with the detail and that’s been a shift. Now I like to study the detail so that it’s very precise. And I’ve arrived at that without really knowing…Rather than creating freedom in the work itself, which can be a kind of trap in performance, I clean the choreography and I feel I have a reason to be out there. It gives me a different freedom—a space to listen and to be present to the moment. For instance, if it’s based on momentum, like the last section in traffic and some of the material in the new solo, there’s still a precision. Even if it’s very loose I can trace it and know it’s going to go through particular positions. I’ve got the template. There are degrees of improvisation and I’m convinced that the structure supports the improvisation I do.

Your work has been getting shorter recently and there does seem to be a particular challenge involved in creating an evening length contemporary dance piece.

It’s the tradition of being entertained as opposed to the tradition of the gallery for example. The length of a work can be a nice creative challenge. I’ve been commissioned to create a 30 minute solo. I’ve done an hour long solo back in the dim dark past and I like the challenge of creating something that long. However, 30 minutes is actually quite long for a solo, especially as I’ve been in this ‘moving-a-lot’ phase lately. I think I’ve been making shorter pieces because what is interesting me is paring the work back. I make copious amounts of material and then I’m very liberal with the scissors. Hopefully there’s enough repetition in different variations or movements through phases so that you do get enough to ‘read’ it. Although I do find it difficult with repetition as such—why you choose to do it.

So what’s the process of cutting back. Why is the choice to eliminate made?

I like to be focused around one idea—put it on the ‘coat hanger’ of one idea. Once that idea becomes clear, then it is also clear what movement is relevant. What I tend to do when I’m making new work is to take threads from the last work and spend a few months reprogramming my body and the other dancers’ bodies, trying to get into some new vocabulary and actually undo the last work. I’ll try and subvert the habits and the familiar pathways, redirecting and getting into some new territory. It’s about trying to create a new vocabulary each time. And of course it’s never completely new; there are always habits and histories. And when you reprogram, that becomes familiar and that is what you want otherwise you wouldn’t be able to create a phrase.

We spend a lot of time creating new vocabulary around some particular movement idea, a physical idea. I describe these ideas in words. I make up words like ‘anchoring’ where one part of the body is stable and things happen around it. Or it could be a relation around a joint, or a shape, then a shifting and rewinding or a change in scale. I find words to describe physical ideas that come out of improvisation and then use them as a score to develop material with. Then it becomes clear what’s in or out, what is relevant to that idea.

So there is a challenge to resolve between doing and talking about what you are doing?

A lot also happens through watching and osmosis. And a lot of words are used throughout the training process that I develop with the dancers, so there is a foundation to work with. You can see it in class—the difference between people I’ve been working with for a while and someone else who comes in and doesn’t have the same field of tools. There are layers of common ground created through training and improvising and watching and working on material: it’s not just about words although we do share words.

There is an evasion of the term ‘technique’ in new dance practices, to avoid locking things into patterns, so how do you describe this common physical language you share with your dancers?

I think there are tools and techniques. There are some things I would say are technical…like having weight in the pelvis and underneath support in the body, as opposed to “pulling up”. And I work with Contact Improvisation as a technique to get people in touch with their weight and have a 3-dimensional awareness of the body in space. There are lots of improvisational and choreographic tools which someone else may call techniques—like how to develop an idea, for example folding and unfolding as a score, shifting levels or speed or emotional quality or taking up more space. I think of those things as tools.

I guess it’s that opposition between technique and ‘original gestures’… the idea that you can evacuate the body of technique and have a blank slate. I always wonder where personal idiosyncracies are meant to go.

I think that’s really interesting. We’re so loaded up and the more technique we do the more loaded up we get. There’s no such thing as neutral body. It’s also just a use of words—you could take ‘emptying’ as a movement score. But getting back to the idea of going past dancing, it’s about how you use your history and the accumulation of sensation information. The older I get the more stuff I’ve got to use. My instrument feels richer all the time, and it will I guess until it starts emptying out…

The history in the body does seem to be a motif in recent Sydney dance performance.

I’m not trying to perform my history, but I’m aware that I am accumulating history. It may be more relevant in relation to my process rather than performance—what’s in my body, what this instrument does or is interested in, the way it works and the way I work it.

On another note, can you tell me a bit about Antistatic, the dance event— the impetus to set that up and how it’s panned out.

Angharad Wynne-Jones (then Artistic Director, Performance Space) set it up in 1997. Mathew Bergan was involved, Sue-Ellen Kohler and myself and Eleanor Brickhill, and others…It was quite a large group. In 1999, I curated it with Sue-Ellen and Zane Trow (the next artistic director). We wanted to bring to the fore dance practices that we felt were not given enough support here and to acknowledge the work of established practitioners who were doing amazing things in these areas and had been working away at it for years. We were trying to elevate their work and open up the notion of practice. It was definitely a choice for me to focus on the newer approaches to the body—Contact Improvisation, Body-mind centering®, release work and improvisation. It was very particular and I think that’s good. It didn’t take care of all aspects of dance, but there’s plenty of time and space for other events that do that. In a way I felt there was a need for positive discrimination.

I did feel very attached to Antistatic and it was difficult when the group was opened up in 2001 [there was a return to a large curatorial committee] and the program was dispersed throughout the year. I’m really pleased that it has gone back to the concise, intense model this year.

Now I’ve stepped out of it and Julie-Anne Long and Performance Space will take it where they want and that’s great. I’ve let go. I didn’t want to leave a half-baked vision for them to realise. I’m sure it will be completely different. I was looking forward to doing it with Julie-Anne. I chose her because I felt she brought another point-of-view and we’d bounce off each other. I also think the climate has shifted and I would not do it the way I did last time. We are not in that space; for example, there is a lot of work happening now that crosses over into text and physical theatre, probably more than there was then. The landscape’s different now and I’m sure they’ll respond to that as much as they can.

–

See RealTime 48 for Part 1 of this interview: “Rosalind Crisp: a European future”, online or on page 28 of the print edition.

RealTime issue #49 June-July 2002

© Erin Brannigan; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

There’s a new ‘grooviness’ seeping into the lower levels of the Opera House. With the opening of the Opera Bar (live music on tap), extending the boutique bar strip from the Toaster almost to the forecourt steps, the possibility of a drink at interval—or sometimes during a show—is bringing a younger, hipper crowd to the hallowed sails. A proactive attempt to tap into this market is evident in The Studio’s programming of Dance Tracks #1 and #2—music/dance collisions between electronically based music outfits and contemporary choreographers.

There was a buzz in the foyer at Dance Tracks #1. Set up like a night club (with plastic bracelets for tickets), the crowd consisted of the softcore dance music lovers come to hear The Bird and B(if)tek and the contemporary dance crowd interested in the choreographic interventions of Kirstie McCracken, Lisa Griffiths and Michael Whaites, and host Lisa Ffrench. The music lovers went home well sated, whereas I suspect the dance crowd left with a queasy sensation that they had been short-changed.

B(if)tek is one of the more performative dance bands. With a baroque geek-girl persona there’s no pretence about how much of their sound is created live. They often leave their stations to daggy-dance to their own tunes. This was fortunate because the choreographed dance moments were few and decidedly uninspired. Michael Whaites’ doctors & nurses Carry On pastiche performed to B(if)tek’s (or Cliff Richard’s) hit Wired for Sound’ showed few signs of serious collaboration between musicians and dancers.

During The Bird’s set Whaites performed a quasi-aerial number which offered a few interesting transitions from ground to air but was rather tame. The highlight came from Kirstie McCracken and Lisa Griffiths in The Bird encore—a pacey piece performed with Chunky Move slickness, all angles and attitude—giving us a glimpse of the potential of the evening. The strongest element was the video work of Carli Leimbach and Kirsten Bradley, including a beautiful underwater dance sequence. There seems to have been more opportunity for collaboration between video artists and choreographers than occurred with the musicians.

Dance Tracks #2 showed signs of learning from program 1. Commissioned by the SOH as part of the Indigenous Message Sticks program it featured PNAU (Nicholas Littlemore and Peter Mayes with Kim Moyes from Prop) and works choreographed by Albert David, Jason Pitt and Bernadette Walong. Here, the focus between the music and dance was well balanced with dance pieces seamlessly woven into PNAU’s set and musicians actively engaging with the dancers. Albert David was great to watch. Moving between states of weight and weightlessness, grace and strength, percussive stomping followed by flowing twists and turns his work (both solo and with Lea Francis) was authoritative, poetic and enthralling.

The highlight of Bernadette Walong’s choreography was a piece in which dancers balanced on drinking glasses. Lisa Davis and Marne Palomares worked their way across the floor intertwining, swapping glasses and shifting body weight on these fragile axes, sensitively accompanied by PNAU and the ringing of the glasses shifting across the floor.

Jason Pitt also experimented with aerial action, creating a skilful work on silks performed by Sha McGovern and Aimee Thomas that utilised the Studio space well. His work on the ground, however, was too choreographically safe to satisfy me. Watching him on the side of the stage, groovin’ to the music as his dancers performed, I longed for some of this relaxed style to infiltrate the performance. As in Dance Tracks #1, the video by James Littlemore was well integrated, especially the piece using dancing brushstroke stick figures which was beautiful in its simplicity

Dance Tracks is an excellent model for integrating artforms that are naturally symbiotic yet so often separated, and it was good to see the progression of the idea from #1 to #2. Dance Tracks #2 showed that success involves a vibrant dance between choreographers and musicians, not just sidelong glances. I’m not sure the Studio will ever feel like the right place for a dance party, and they’ll need to be careful to avoid merely skimming the cream off well established cultural scenes, but hopefully the Studio will continue its commitment to producing original collaborations, collisions and confabulations.

Dance Tracks #1; musicians B(if)tek and The Bird; choreographers/dancers Michael Whaites, Kirsty McCracken, Lisa Griffiths, hosted by Lisa Ffrench, video Carli Leimbach, Kirsten Bradley; April 26-27; Dance Tracks #2; musicians PNAU; choreographers Albert David, Jason Pitt, Bernadette Walong, Video Jason Littlemore; as part of Message Sticks, May 24-25; The Studio, Sydney Opera House.

RealTime issue #49 June-July 2002 pg. web

© Gail Priest; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

One of the things I like about Topology is their insistence on communicating with the audience. Their program guides have notes on every piece, and URLs for some of the composers and also for the band. Often one of the performers will speak a little about the piece they are going to play, but chatty, not too Adult-Ed. And because they premiere a lot of works (tonight is no exception) it is often useful.

Tonight the concert is about music and generative processes. Sometimes the process generating the music is maths, and obvious, sometimes it’s loose and subtle. All of the pieces are at least predicated on the idea that systems can generate worthwhile music.

A selection of Tom Johnson’s Rational Melodies provides a linking device throughout the night. These are the most overtly generative pieces of the night, and sometimes are a bit too simple to be interesting. Johnson works along the boundary of audification (direct mapping of data to sound) and music. Worth a go. You can try one at home. Play the first note of a scale. Play the first note, then the second note in the scale. Play the first note, the second note and now the third note…Keep going until you’re playing all the notes in the scale, then stop.

So some of the Johnson’s were better than others, and only a couple of other works didn’t work for me. Nyman’s Shaping the Curve was a little formless, and ended up having that ‘one thing after another’ effect. Same for Davidson’s second piece, Squaring the Circle.

However there were plenty of goodies. Bernard Hoey played the first two compositions from the 6 part Viola Sonata by Ligeti. The first, Hora Lunga, is based on the natural harmonics of C. Slow and lyrical, the unusual tuning works a dream—expressive, coherent and consonant, but not quite normal, not quite right. Perfect to convey longing and the melancholic approximation of ideals. The second piece, Loop, is fast, structured, virtuosic, double-stops all over the neck. A stunner performance. Big ovation.

Thou Shalt!/Thou Shalt Not! by Michael Gordon (from Bang on a Can) was another good piece with a performance to match. It’s a strange piece that deliberately prevents the building of momentum by interpolating stilted percussive sections into the larger ensemble performance. This gives a repetitive, disappointing air to the piece that somehow works without becoming monotonous. About half way through, Robert Davidson pulled out the electric guitars and started up a distorted chunky rhythm that sounded like a chicken playing the kazoo. Perfect.

Other memorable pieces. John Babbage’s jazzy Chop Chop, and Jeremy Peynton-Jones’ Purcell Manoeuvres. Based on Purcell’s Trio Sonata #7 in G Minor it still sounded like Purcell, even with all the algorithmic modifications to the old guy’s composition. As always, I came away from a Topology concert chatting away, thinking about buying a CD (the Ligeti), looking forward to the next one.

–

Topology, Rational Melodies, Powerhouse centre for the Live Arts, Brisbane, March 28

RealTime issue #49 June-July 2002

© Greg Hooper; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

When is live, live? If it’s not live, is it dead? Can it be half-live? How much equipment can be used before it’s dead? These are questions arising from contemporary music/sound performance. Stelarc provokes considerations of ‘the body’ against ‘the machine’ in an obvious visual way—with half a ton of metal hanging off him. Musicians, however, have been sonic cyborgs since the coming of electronics to sound. With the current popularity of laptop computers as instruments, the divide between the performer’s body and the sounds produced is emphasised. Like the mouth and eyebrows of a guitar player which dynamically narrate the ‘hotness factor’ of the sounds at hand, the nostrils and corners of the eyes of lap-toppers dance a funky beat to the shifts of their controller data.

Melbourne digital media artist SEO (Jeremy Yuille) uses a games joystick to control the sounds coming from his laptop. The set-up includes the laptop on a music stand at about stomach height, and Jeremy standing about arm’s length behind it. Using the joystick as an interface allows his body, rather than just fingertips, to be involved in the performance. Jeremy’s face is alive with concentration: reading his controls on the screen and reacting to the sound from the PA. He shifts from one stance to another, moving with a slow grace. The scale of the movement is reduced—down from the 100% physicality of a drummer or dancer to a more subtle 10%, but the body moving with the music none-the-less.

Traditionally, musical energy flows from bodies. But with computers “you can just hit return and have 16 channels of anything” (Violinist Jon Rose, in Andrew Beck, “totally huge: it’s what you do with it”; RT # 43 p39). Taking this to an extreme is a Merzbow performance— Masami Akita seated calmly behind Powerbook, his mouse-hand twitching as if he is playing Pac-Man, as the audience is practically eviscerated by a barrage of searing white noise. Hrvatski, a U.S. drill and bass producer, admitted that his role when playing ‘live’ is to hit ‘play’ and ‘stop’ at the start and end of each song. During his set at the 2001 Electrofringe Festival, he jumped into the audience to dance to his own music. This kind of makes him a DJ. Putting electronic and particularly computer-based performers on a continuum with DJs is important in understanding what is going on in contemporary music performance.

The DJ has been accused of being an overpaid prima donna (the same accusation levelled at conductors), stealing the glory from the people who ‘actually make the music.’ They portray, however, a realistic relationship between technology, the audience and the performer. 99% of the music we hear is recorded, and the role of humans playing live is both optional and discontinuous—present in the same way the violinmaker is present in a recital.

Bands are the worst offenders, cherishing the live performance, the direct connection between their soul and the audience; but happily using pick-ups and mikes, effects pedals, amps, compressors (etc ad infinitum) and the PA —all of which is conceived and performed by faceless sound engineers. (To come clean here, my other life was as a faceless sound engineer). Who is ‘the Band’ trying to fool with its ‘honest’ live performance using ‘no digital sequencing devices’ (‘Area 7’, 1999) or ‘studio trickery’. If you want live, go busking.

SEO (Jeremy Yuille), Oven-Garde, Melbourne, April 1. Oven-Garde is a performance series held on the first Monday of the month at the Builders Arms Hotel, Melbourne, and is presented by the tRansMIT sound collective.

RealTime issue #49 June-July 2002 pg. web

David Toop was one of the first experimental musicians I became aware of, as a wee tacker back in the 70s. He gave one and a bit talks at REV. Very personable, fireside-chat-like. The first talk was on his life in music (so far). It went Suburbs, Normal non-musical Mum and Dad, Radio, Comedy records, the Goons, Quatermass, all that BBC radiophonic stuff, Bo Diddley and homemade guitars. (I first heard of David Toop as the man who'd played the world's slowest guitar solo. Impressed me at the time seeing as this was 70s stadium big hair rock days ). In the 70s Toop became interested in the physicality of sound production and formed a long term friendship with Max Eastley, making and performing on large scale sound installations. Another consistent interest of Toop's has been constraint-based or scenario-based performance. Asking the question: What can I get out of this seed pod, a peg and a balloon floating away? An approach used now by people like Matmos.

Across both his talks, Toop returned to the relationship between technology and performance—particularly in the era of the laptop performer. Toop is not just wanting to spice things up (ie add a video wall), but asking what is the nature of human engagement with performance as perception and action, audience and performer (see also Paul Lansky). This is a critical issue with plenty of room for more exploration.

At the end of the second talk, shared with Scanner, a woman, the oldest person in the room, started talking during the audience participation bit. Oh no! Methinks: some irrelevant boring old granny reminiscences. Well, what a bigot I am. These few minutes of Joan Brassil talking about her work were a highlight of the festival, and not just for me. The audience, Mr Toop, and Scanner were more or less stunned as this elderly woman described the wonderful work she has made. Sophisticated, subtle, and humane. We keep hearing the world is full of amazing people, well one of them was there, sitting amongst us, a secret til she spoke. David Toop's response was “I must talk to you about the next exhibition I'm curating”. Yes he must.

Sound Body, David Toop, as part of REV, Visy Theatre, Brisbane Powerhouse, April 5; Wave form versus liquid breath technique, David Toop & scanner, as part of REV, Visy Theatre, Brisbane Powerhouse, April 7

RealTime issue #49 June-July 2002 pg. web

© Greg Hooper; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Saturday night of the REV festival and a large crowd gathered for another instalment of fabrique at the Powerhouse's Spark Bar. Many punters had just emerged from the preceding Diversi A and B concerts and headed to the bar for a drink and a chat while others were drawn at the end of the day by the promise of high-profile international names. The previous night had been an exclusively Australian affair but tonight two UK sound artists were headlining: David Toop and Robin Rimbaud (aka Scanner).

First up though was Sydney-sider Oren Ambarchi armed with a highly customised electric guitar and a bag of effects units and floor pedals. His vibe at first was purely ambient/minimalist as now and then he plucked a single spare note on the guitar, barely seeming to move. Fed into long, cycling delays these notes formed lines of virtually imperceptible ostinatos that slowly accumulated into a shifting sea of tones. As the density of the tonal liquid increased so did Ambarchi's movement, leaving the guitar to manipulate effects and keeping the currents moving. Inexorably the guitar tones began to disappear and the oscillations and granulations of the effect devices themselves took over as Ambarchi focussed on turning up the level of energy until the grating noise machine seemed to choke itself to death. The performance was entrancing in its slow organic progression and proved to be the highlight of the night for me.

David Toop continued the axe assault by improvising on a Hawaiian guitar with various Inquisatorial torture implements including pieces of pipe, an electronic bow and a range of effects pedals. Toop's work was multilayered consisting mainly of ambient wefts on CD used as a bed for improvisation on guitar and flute with acoustic and electronic manipulation of the instruments. God was in the detail as Toop's improvisatory gestures responded to elements emerging from the intricately crafted background–at one point he even played a descant to microphone feedback using the flute! Unfortunately much of the detail required close listening which was generally impossible in the hubbub of the Spark Bar.

With the second UK artist, Scanner, the vibe shifted into club mode with more familiar harmonic structures and greater rhythmic energy which pulsed with the ambience of the venue. Scanner is one of the breed of laptop warriors and proved a crowd favorite as he extracted and convulsed material from Mini Disc and portable synthesisers with the aid of software on his Macintosh. At times he leaned towards a deconstruction of the bombastic stylistics of anthemic dance music and at others ventured profitably into areas of ambient glitch producing a very polished and structured performance set.

Amorphous Brisbane electronic outfit I/O comprising Lawrence English and Tam Patton finished the night on a postmodern note with improvised turntabling and more laptop action. As Patton scratched and droned with the vinyl, English sampled, fragmented and reconstructed the sounds in real-time using interactive looping software. In a departure from general DJ practice, rather than focusing on the prerecorded material on the records, the performance emphasised the grain of the medium itself.

Overall, perhaps what struck me about the night was that though fine music was being made nothing really new with regard to experimental performance practice or sound production was offered. All the artists worked with techniques and processes that have become part of the canon of electronic art music, whether it was Ambarchi's delay effects, Toop's tortured Hawaiian guitar or Scanner's deconstruction of dance club aesthetic. Is the revolution in electronic music over? Am I just nostalgic for some dubious thrill of avant garde unexpectedness? Of course it's inevitable that “new music” will become generic and that those genres will stabilise and become respectable (for want of a better term). Rather than being revolutionaries these artists are working now with the rich results of a revolution consisting of a range of mature and highly sophisticated techniques along with an accumulated tradition of experimentation. QUT Creative Industries' intellectual and capital investment in the REV festival as whole demonstrates that these genres and techniques are now pedagogically viable concerns. However much we might grasp at defining what is new music it's probably what slips through our fingers that will end up surprising and challenging us.

Though the REV festival has finished, fabrique continues throughout the year at the Brisbane Powerhouse under the guidance of Lawrence English and promises the chance to hear more Australian and international electronic acts continue a rich tradition of experimental music.

REV Festival, fabrique, performers Oren Ambarchi, David Toop, Scanner, I/O, Spark Bar, Brisbane Powerhouse, April 6

RealTime issue #49 June-July 2002 pg.

© Richard Wilding; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Steve Langton's Pyrophone

Sunday night for the last Roving Concert. A group of us are led about for a 10 to 15 minute performance from each of 5 groups. A bit of a taster, and it works well. First up is the Pyrophone (fire heats the air in huge organ pipes) from Steve Langton and Hubbub. It's outside, at the front of the Powerhouse: a designer-shabby industrial wall, flat slab, rough concrete, maybe 15 to 20 metres high. Up against are a few vertical stacks of giant exhaust pipes, steel tubes going straight up. There's a large crowd. The act is a bit corny-leather jerkins at the forge, reverence for the primordial mystery of fire etc-but the sound is massive, body-shaking, and the jets of flame make for great visuals. Crowd pleaser #1.We then troop off indoors for the Sarah Hopkins' Harmonic Whirlies. The clear, diffuse sound is generated by whirling plastic hose (think pool vacuum hose) around at various speeds in a cross between call and response folk dance and harmonic singing. Great exercise.

Next! David Murphy's Circular Harp. Vibrations from hammered strings are fed into bowls of liquid. This makes patterns which are projected onto a large screen. Real-time correspondence between the visual and the auditory. A bit like a physics lesson in dynamics, but with art instead of physics. After that come the massed handbells, more audience participation and clear sounds. Then Stuart Favilla's light harp and Joanne Cannon's serpentine bassoon. Good bassoon, but the light harp is not much. When you replace harp strings with narrow beams of light the fingers brush against nothing. This reduces the ability to make fine motor movements and articulate sounds—no anchor and pivot, no force feedback. That's the way our sensory and motor systems work. Exploit it, don't deny it. (see Gail Priest's alternate view of the Light Harp)

Last up is Linsey Pollak's ewevee, out on the Brisbane River played by Pollak and Jessica Ainsworth. A vertical set of bars are struck to trigger samples. The samples attached to each bar are changed, giving totally different sonic effects for each piece. A nice play between the physicality of the instrument and the virtual nature of the output.

Short sweet performances. If you didn't like one you'd like the next. If you didn't like any then you don't like music much.

Roving Concert, part of REV, April 5-7, Brisbane Powerhouse.

RealTime issue #49 June-July 2002 pg. web

© Greg Hooper; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Fabrication: the making by art and/or labour, an untruthful statement; to fake or to forge the process of manufacturing.

Macquarie Dictionary

A festival based on new fabrications, and “ideas” about music and sound (to paraphrase executive director Zane Trow) inspires much questioning, especially when it brings so many ideas people together. My brain started ticking when David Toop commented to me that performance was no longer a useful term for much of the electronic-based sound-making practices at REV. We are in a phase of transition he suggested, before expressing his deep disquiet about the validity of his own sedentary ‘performance with a laptop’.

Set the task to concentrate on fabrique, a cabaret of electronica and sonic electro-hybridity, and Silent Movie, a live jamming session of REV artists to Russian Dziga Vertov's revolutionary film, Man With a Movie Camera (1929), a number of questions occurred to me.

What do the interfaces to REV’s new media instruments contribute to the performative experience? For example, Greg Jenkin’s pluckable, sonic cacti spines, Amber Hansen’s jangly miked-up jewellery or the ubiquitous laptops utilsed by Pimmon/Scanner/etc. And should we need to understand them more fully in order to accept their roles in performance?

What are the issues of mapping that these new instruments imply? We understand the basic mapping of a grand piano as being a relatively clear relationship between finger velocity, subsequent mechanics, appropriate string tension, physical collision and focussed sound emission. We know what the performer is grappling with, so we focus on the sonics rather than the mechanics of the experience. But it’s much harder to know quite what these R(eal) and/or E(lectronic) and/or V(irtual) instruments are, and herein, maybe, lies a problem. We know that the computer long ago destroyed the relationship and fixity between inputs and outputs. Forever. Hence new performance tools based on computers allow deeply convoluted and dynamic mappings of input action and ultimate sonic response.

So, on that basis, what were the virtually invisible sound artists Scanner and I/O actually doing up there on the roof during the installation/performance Biospheres, Secrets of a City? Was it performative? Now you’d never ask that irritating question of the venerable Jon Rose. His virtuoso performance of an augmented string instrument, using the violin and bow as interface to trigger a bank of sound generators consummately succeeded in mapping action to sonic outcomes.

At REV it seemed that almost any device capable of either self-generating or responsively generating electrical impulses was being employed as a playable interface. For example, performance sense was made through the use of inductive, magnetic coils (Andrew Kettle) or through miniature microphones picking up surface textures (Michael Norris). There were the resolutely digital instruments triggered in the main by velocity sensitive synth keys, MIDI actuators or computer keystrokes (aka Pimmon, Hydatid, Rene Wooller etc). Somewhere in between lay a rather clunky fish-shaped device used to trigger granular-synthetics via MIDI (Tim Opie) and a performer in a Yamaha MIDI body suit producing, through rather mechanical movements, a broad range of sampled sounds ([de]CODE me directed by Lindsay Vickery).

All of these diverse forms of gadgetry were being used by their performers to create sounds for subsequent processing, or to actuate virtual banks of preset and ever changeable sounds. Then of course each performance’s sound mixer could completely re-affect the balance of almost everything before we finally heard it. All this became the means for generating REV’s new sounds. Needless to say, any attempt at reverse engineering on the part of audiences was largely futile.

So what might a performer do to help those of us who care, are curious or simply need to know? Should those players, lit only by their laptop glows, apparently devoid of fingers and face behind their flip up screens demystify their mappings, given their choice to perform rather than be downloaded? (In welcome contrast, REV’s accompanying installations each had an attendant on hand to explain and demonstrate, interface, mapping and intent).

Many might be asking by now, is this line of questioning simply a cul-de-sac? Is the desire/need-to-know actually a major barrier to bringing new, electronically mediated forms to a place worthy of the tag ‘performance'?

This question is integrally tied to how we choose to make the transition to new performance forms. I for one hope it will be towards the ‘transactions’ so characteristic of performance forms that acknowledge their audiences as integral.

Toop is right and, by the way, REV is definitely pushing the right combination of buttons to get there.

REV Festival, Brisbane Powerhouse, April 6

RealTime issue #49 June-July 2002 pg. web

© Keith Armstrong; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

There is no doubt that the arts can seem unimportant—even trivial—in the wake of traumatic events, including September 11, the refugee crisis, the war in Afghanistan and ongoing but pressing Indigenous issues in our own country. In truth the arts have suffered for years from the perception that they are unimportant. Our news and media outlets fill their entertainment and lifestyle sections with little but celebrity gossip and box-office grosses. And if we indulge in entertainment when the hard times take hold, it is because it offers the security of escape.