Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

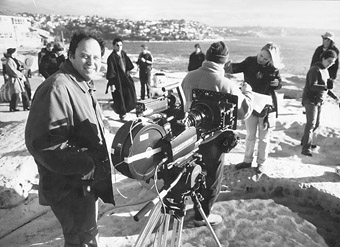

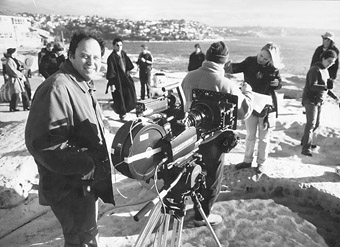

Like the best of modern dancers, Bebe Miller watches movement intently. At her Melbourne workshop presented by Dance Works in June this year, the New York choreographer asked the participating dancers to “take the idea of weight being at risk and allow an interruption to happen.” She wants them to avoid the familiarity of their known dance vocabulary, or its beauty. “How does an interruption become a staccato pattern? Why is that dissolving gesture a continuous thought rather than a break with form?” The dancers struggle with these ideas in their improvisations. Katy McDonald has one foot curved under while another foot is flat, then she flips her body over like a tensile cat. Miller responds with a series of strategies to intervene in the phrasing of movement-hair-pulling, visual or aural distraction, speaking in one ear, manipulating body-parts.

Later in conversation, Miller explains this idea of interruption, as both an aesthetic and political act. She is interested in the ‘civilian body’, a body available to the dancer outside her training but which becomes buried in the habit formation of dancing. “It is only when we know that we have habits that we can use them. Why is the habit of ‘light touch’ always about the same temperature and the same weight in relation to the task at hand. If you change that, then what do you feel? Or resist it? And what if you follow through?” This habit change involves utilising the pedestrian to interrupt the codes they have as dancers.

Political dimensions of being seen as dancers with civilian bodies are linked to interruption. “Studio practices have myths about equality and about mood as if you accomplish what you need to within given rules. But I’m not here to make everything equal. Two men together carry a charge, 2 women, black and white – we live in this world where those things are real so I try to let that be visible.”

I ask Miller where choreography is going in the 21st century? “I think we’re in the middle of a 40 year shift and time is not on our side. I feel there is a path towards relevancy. I went to Eritrea in Northern Africa a couple of years ago for 3 weeks. I’m in a foreign environment and I had this sense of them looking at me intently while I’m looking at them intently. They are looking at someone foreign inside something familiar, so we have a different point of view in terms of intensity. What is that about? Is that something that I can capture in dance? As I work on it, it occurs me to that that difference of gaze is political. It shows up in Ohio, it shows up in Pakistan and Palestine. What seemed like a foreign adventure is in fact localised. So the choreography is about how I can use the home environment, not recreate an African experience. It is not just about race, it is about vibrating in a different way. That is the ultimate test of globalism, can you allow that body vibrating differently to be next to you.”

Her voice in class says “go-girl”and “Yeah! Yeah! “and “oh, hello” when she sees an interruption that vibrates. In watching, Bebe Miller shares this potential for dancing to create physical or psychic change even though she does not know where the choreography of civilian bodies might go in the future.

Bebe Miller workshop, Dance Works, Melbourne.

RealTime issue #51 Oct-Nov 2002 pg. web

© Rachel Fensham; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Fortyfive Downstairs, once a gallery now a gallery and performance space, hosted a winter collaboration between art and dance, entitled Focus 4. During its season, the space was arranged by placing 4 installations side by side, and nightly cameos in a vestibule. Its audience was led into each constructed situation to bear witness to the dancerly component which brought alive each installation. Dancers and artists integrated their work to differing degrees, with some constructions necessary to the dance, some complementary, some autonomous and others a hindrance.

Stephanie Glickman’s movement bore great allegiance to Michael Sibel’s large, steel sculpture (a conical monkey bars). Glickman sought inspiration from the limitations of bounded space, climbing, weaving, and swinging from steel bars. Here, installation offered an aesthetic puzzle, which provoked Glickman towards a bold clarity of exploration. By contrast, Benjamin Gauci and Louise Rippert seemed to mirror each other: both working in a minimalist sense, whether with white ceramic shapes and flour, or repeated circular movement leaving floury traces. Together, a sense was created of gentle but insistent assertion. Marc Brew’s collaboration with a wheelchair produced some beautiful inversions, where it could have been either chair or body as installation. Brew’s dialogue with his own body suggested the kind of play with structural givens that Glickman found in Sibel’s sculpture.

Glickman, the curator of the show, wrote that the dancers and visual artists did not know each other before working together. As might be expected, such a risky venture is likely to lead to contrast as much as integration. Naree Vachananda’s very personal and moving work was framed by but not particularly connected to Anna Finlayson’s mural collage, whilst Benjamin Gauci’s strong, balletic composition positively crashed through Louis Rippert’s hanging fabrics.

The variety of relationships between artist and dancer taken collectively offer food for thought as to the range of ways in which one form might collaborate with another. Not forgetting that Merce Cunningham’s own option was to combine at the very last minute, allowing different elements—music, lighting, sets-to freely juxtapose.

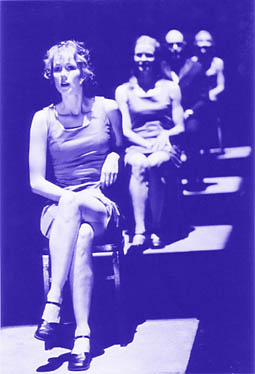

Tracie Mitchell’s recent work, Under the Weather, was quite different in texture to the above. Although it combined video and dance, there was a sense of an authorial aesthetic, emerging from a single perspective. From dark beginnings, a video triptych blinked and winked, creating a powerful portraiture of urban existence. Dancers emerged from the shadows singly or together, drawing elegant lines. The set fanned out from a recessed centre, suggesting that something was being aired, turned inside-out. Dancers ventured then retreated, hidden again by shadow.

There was a section where each dancer performed solo. Carlee Mellow’s work was striking, precise, quirky, repeated just enough to gain familiarity with her vocabulary. It was also enjoyable to watch Mia Hollingworth and Shona Erskine move through what appeared to be their own material subjected to Mitchell’s careful direction. Sadly, the piece ended before the 3 dancers were able to come back together. So much had been created and established that a desire was born for hiatus and closure. Instead, the piece gently fell into shadow, leaving an opening where before there was none.

Focus 4, Stephanie Glickman & Michael Sibel, Nicholas Mansfield & Andrea Meadows, Benjamin Gauci & Louise Rippert, Naree Vachananda & Anna Finlayson, Marc Brew, and Amelia McQueen, at Fourtyfive Downstairs, Flinders Lane Melbourne, Jul 26 -Aug 4

Under the Weather, choreographed and directed by Tracie Mitchell, performed by Shona Erskine, Mia Hollingworth and Carlee Mellow, music by Byron Scullin, Gasworks, Port Melbourne, July 23-27

RealTime issue #51 Oct-Nov 2002 pg. web

© Philipa Rothfield; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Hold that deadline. Other cultures from ours experience time and the detailing of events, and hence, meaning, differently. In particular, there is a concept of “thick time”, a Balinese term for when events and significances line up in a particularly dense overlay of resonances (John Broomfield, Other Ways of Knowing, 1997). I begin to wonder whether, in improvisation, “thick time” becomes a condition of performance: from the initial, tentative setting-up of an idea, or partnership, through to the layered, richly-confluenced zone of thought and action that looks and feels expanded, hugely spacious, where the span of a single breath is wired to so many options (and organs), words, shudders and slides, that one is not holding, marking time, but that it holds you. Helen Omand says: “The best improvisations are when it seems like the score has already been written in space/time, and the body makes it manifest” (RT 45 p11).

To improvise is to enter a zone approaching the infinite that is yet bounded with finitudes: muscle, step, language, wind. In their finer moments, the most seemingly divergent practices-from Grotowski’s “shedding of resistances” to the classical acterly “training up” to form-also whisper each other’s virtues, hugeness meeting the particular (or vice versa) in multitudinous intimacy. I observe the final session of Precipice in Canberra-not, alas, the fall of the incumbent rulers from their parliamentary spire, but a 4-day improvisation jam, now in its 9th year-and reflect on some of the “givens” of the artform.

Trust. Trotman and Santos in partnership reveal an intimacy that is verbal, physical and structural, with structure a distinct body with its own edges joining in the play. Their interplay seems helix-shaped, diverging, converging, holding their differences in a brilliant interweaving. Santos, glowing-eyed, ‘redeems’ them from the edge of chaos, insisting on the unity of their ‘two becoming one” whilst Trotman falls off a cliff with the other billion into which they have already multiplied. Two gaspingly beautiful moments where their two distanced bodies turn as one.

Ghosts. They show their training, as performers do when they improvise. Trotman and Rees-Hatton through Al Wunder’s Theatre of the Ordinary sharing a tendency to separate words from movement in alternation. Trotman’s words left gasping, arms grasping; peculiar and particular, a quaintly-disjuncted relationship to impulse recognisable as a TOTO influence, yet here ignited with a special resilience and wit. Rees-Hatton belies her maturity with hops and skips, an adult dancer partaking in an all-day lollipop.

Hitching on the glitches. Ryk Goddard plays tag and chasings with patches of light which cut out just as he arrives. An at times harrowing biographic discursion on finding and keeping home, of an identity teetering and lurching away from stable balance. Both verité confession and postmodern artifice, the bravely darkest and most personified piece of the session.

Possible vs impossible, known vs. unknown. Barnes and Bonnar tease out the tango form, decaying, redeeming, querying and quarreling with it as their feet wickedly flick and sashay. A delicious turning-over of a form that already leaves itself open to unturn, tickling at (in)competencies and (in)complicities. His solid body helps her into a backbend, drags her metres across the ground; their roles reverse, she’s surprised to be caught in an impossible expectation to do the same.

From intensified abstraction…. In a butoh-based slaughterhouse blues, Pemberton, O’Keefe and Hunt alternate slack-hipped mimickry of cattle-men with Body Weather incursions into the muscles of slaughtered bovine souls. Blood on the hay, buttocks jammed in corridors. Kimmo Vennonen’s soundtrack veering from literal to a blood-journey through the internal nightmare.

…to dissolution. We emerge in late-afternoon wind and light to Alice Cummins’ silver hair reflecting the agedness and deepgnarled beauty of the courtyard’s central tree. At times her relatively still body seems to sprout from it, at times nearly fall like a leaf, or suspend from within it like a limb; thence dance along its skin, a difference of time and density. Cummins afterwards expresses her consciousness of being the final performance of the weekend. In what way might such consciousness interfere? The show must go on, but performances stop, do they? Cummins’ performance aptly softened the rhetorical edge of the season’s title with a grace and heart that rendered time thick and thin as water.

Precipice, Peter Trotman, Lynne Santos, Lee Pemberton, Anne O’Keefe, Victoria Hunt, Kimmo Vennonen, Sarah Bonnar, Gary Barnes, Ryk Goddard, Noel Rhees-Hatton, Alice Cummins; lighting: Mark Gordon. Australian Choreographic Centre,

RealTime issue #51 Oct-Nov 2002 pg. web

© Zsuzsanna Soboslay; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Nightshift 's latest incarnation has increased the work magnificently in scale, complexity and duration, and is magically immersive in Artspace's largest gallery. On opening night, guests disappeared into the darkened space for long, satisfying reveries, wandering amidst the large transparent screens, intrigued by the flickering images reminiscent of peep shows, silent movies and film noir, but uniquely something else-a curious meditation on dance movement and sexuality. Images multiply and enlarge across the space with a photographic intensity and viewers become a shadowy part of the picture themselves in this intimate walk-in cinema of desire. The addition of extended movement passages to the original enigmatic glimpses of McPhee and a more audible and developed sound score confirm Nightshift as a major work in new media arts.

Nightshift, Wendy McPhee & George Khut, Artspace, Sept-Oct 14

RealTime issue #51 Oct-Nov 2002 pg. web

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

I used to think sound art was about the sound of sound. After engaging is a crash course of events and recordings, I discovered that, similar to more traditional music, a lexicon of noises generated electrically and digitally, has emerged that one can become accustomed to, begin to absorb as naturally as equal tempered tuning. So experiencing a sample of What is Music? events, I came to the (perhaps belated) revelation that more than just being about sonic textures, sound art is often about discerning the (sometimes apparent lack of) relationship between the modes of production and the sound they make.

Saturday night at The Studio, Sydney Opera House, offered a program jammed with different methodologies of making. Jim Denley opened the evening in acoustic mode, playing a saxophone and contact mike. Circular breathing, he created a gurgling drone textured by mouth clicks, tongue tocks and breathy grunts. At one stage the only sound you hear is the scraping of the mouthpiece over his stubble. The performance appears to be an exploration of air within the curls and corners of the instrument, an internal examination of the instrument itself. Joyce Hinterding, tuned us into the ether with aerials, computer and mixing desk. She created an increasingly dense carpet of drones out of electrical hum, tuning into higher tones and buzzes, tapping into slower, loping waves that chopped up the air around us.

Robin Fox and Anthony Pateras launched into a sonic maelstrom, Fox on computer and Pateras virtuosically pounding a small keyboard and activating changes through a breath activated mouth piece. Then just as suddenly the chaos pared back to a respite of a metronome looped and effected. Pateras then took to the strings of a deconstructed piano with kitchen cutlery, chopping and impaling the notes further manipulated by Fox. Toshimaru Nakumura and Sachiko M created a cool, quiet world of machine made sine waves, electrical pings, and pulses. There was no layering, just pure tones introduced for a few seconds and then removed. Binary, on/off. Phantom tones and warm hum of air conditioning. All moments controlled and measured.

Ottomo Yoshihide dragged us back to gritty earth with an improvisation for guitar and record player. He used the guitar to generate drones, occasionally moving into a rock-god lick of suspended notes, pumping up the overdrive, creating loops that hit the torso and kept cycling long after. (I am told it was an Ornette Coleman standard and must admit to ignorance on this one). Finally he threw a cymbal onto the turntable creating a manic carrillion, your head stuck inside the bell. Some couldn’t handle it, others stayed to the bitter end mesmerised or paralysed by its delicate obnoxiousness.

A regular feature of What is Music? is caleb k’s impermanent.audio—this year at PACT in Erskineville, creating a kind of rock concert feel compared to the intimacy of Hibernian House. Ai Yamamoto (Japan/Aus) on laptop (also running visuals) created a dense yet delicate sonic landscape with cascading streams of sound-notes and noises rippling over each other, constantly descending. Her palette of sounds is exquisitely created, concise, crystalline yet full bodied. She manages to produce under-rumbles with no grit in them. It is a stunningly “pretty” sonic universe. Anthony Guerra (Aus/UK) cycled feedback round the speakers, round your brain, with pops and glitches keeping the space unpredictable. He fused the sound into a massive perverse growl, both beautiful and ugly, which eventually pulled back to where it began. Snawkler started with acoustic samples, fingers on the fretboard of a double bass. Their use of samples is like unfinished thoughts of multi-streams overlapping, clashing, overriding other frequencies, a kind of cutup orchestral chaos out of which sonic thought bubbles arise. Their second piece using gamelan samples is a beautiful exploration of glassy and metallic colours. Günter Müller (Switzerland) and Tetuzi Akiyama (Japan) provided an improvisation, interesting in the uneasy differences of sound production. Müller bowed small gongs and metallic objects and played with the overtones, while Tetuzi Akiyama investigated (again) the sonic qualities of an electric guitar—running a metal ruler over the strings, applying things to the velcro strip attached to the body-nothing more than an exploration of the exploration. SEO performed with a joystick, and created sounds that seemed to have lost their video game. Standing in front of the audience, shoes off ready for action, he toggles the stick with full bodied gestures, manipulating loops of hysterical voices and agitated intonations that accelerate and escalate like a car race. I’d be interested to hear works with other sample palettes. Toshimaru Nakamura, played once again, but solo, in a similar vein to the studio night, with simple tones, emphasising the negative aural space—the trains to Erskineville, the sneezes. At the end of a program of such dense sound moments, his work was like a cleansing of the aural sphere.

In only 8 years Oren Ambachi and Robbie Avenaim's what is music? has become a vital celebration of Australian sonic explorations, exploitations and manipulations. After the hangover, activities will continue in dark corners, warehouse and white gallery cubes around Australia, spurred on by the growing sensation that there really is something significant going on here, beginning to impress itself on the Australian cultural psyche and the international scene. Many sonic loving (are we batlike?) creatures await, ears back, for the next instalment.

what is music?,The Studio, Sydney Opera House, Sat July 21, impermanent.audio, PACT, Tues July 23.

RealTime issue #51 Oct-Nov 2002 pg. web

© Gail Priest; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Dante Alighhiere’s The Inferno is a remarkably visual work that records the poet’s imagined pilgrimage into the vortex of the damned, phrased in 100 Cantos of 1292-style vernacular Italian poetry. It is the first work of the Divine Comedy trilogy, written after he had been exiled, a victim of the political chaos and corruption of medieval Florence. Hence it paints a vivid picture of Dante’s yearning for the earthly triumph of human potential in an era of deep injustice, corruption and unfettered greed. It’s not surprising then that such a subversive, political allegory still holds much currency today.

It was this model of symbolic retribution that inspired composer John Rodgers to create this modernist, sonic epic for Australia’s national contemporary music ensemble, ELISION. Appropriately they chose to present The Inferno as an installation, placing numerous performers throughout the abysses of Brisbane Powerhouse’s main theatre with grand-scale video projections (by Judith Wright) at each end of their netherworld.

Throughout most of his journey down through the Circles of Hell, the pilgrim Dante had the benefit of the poet Virgil as his personal guide. However, despite such unfettered access to the “voice of reason” even Dante ultimately required further assistance in navigating those deeply complex terrains (provided by Beatrice,symbol of Divine Love).

Anyone who takes on a work like The Inferno is nothing if not ambitious. While attempts at direct illustration are undoubtedly futile, plenty of well-signed guide posts are required to avoid audiences feeling like lost souls groping to “see” horrors in the darkness, such as the Vale of Suicides, the marsh of the Styx or Cocytus, the frozen centre of Hell. Rodgers describes in Real Time 36 (‘Sacred Geometry’, p. 43), how he went about structuring an “architectural” spectrum for audiences, visualising “each instrument’s sound world” as “a microcosm of Hell.” Tactics he employed included electronically generated drones, extreme degrees of distortion and the construction of complex arrays of “multiphonics.’ These were skilfully produced by ELISION’s manipulations of instruments as diverse as slack-stringed violoncellos, bowed polystyrene boxes and water damped Cretales, and, impressively, a flute and oboe cast from ice leading to an audio-visual meltdown. However Rodgers admits in the same article that “most” audiences would miss his numerous Dante-inspired “details”, yet still remain satisfied by a work that does “not need to have any relationship to Dante’s poem”.

Whilst Rodger’s composition offered a generous viscerality it lacked the deep visual sensibilities of Dante’s words. Hence I looked to Judith Wright’s accompanying video text for my guidance, given its significant placement and physical magnitude. Subtly timed interactions of sound and image have undeniable power within new media performance allowing audiences to vividly ‘picture’ for themselves. However with the visuals provided I frequently struggled to conjure up Dante’s incendiary visions of corrupt contemporaries, tortures beyond the pale or indeed much of his imagined geographies.

Suffering therefore from a disorientating blindness, I gratefully alighted upon Murray Kane’s poetic essay in the accompanying program: “‘ How will I recognise Styx’, I asked? ‘Sullen Strings choking on fumes of spite’, he replied matter of factly”.

Inferno, Elision Contemporary Music Ensemble, Brisbane Powerhouse, July 5-7

RealTime issue #51 Oct-Nov 2002 pg. web

© Keith Armstrong; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

In the early 90s there was a possie of us all hurtling ourselves through the air and swinging from things, but some of us got a bit tired, a bit hurt, had to get jobs, and it seemed like the Sydney aerial scene went into hibernation. But since 1999 Aimee Thomas and Shelalagh McGovern have been determined to make things, mostly dangerous looking things, happen with their creation of Aerialize-Sydney Aerial Theatre.

Big in Japan was their annual celebration and fundraiser. Described as a night celebrating Asian influences on Australia, the Newtown Theatre was gorgeous decked out like an old music hall with flowing red silks, origami sculptures and a huge scenic backdrop framing the live musicians, Entropic and Deepchild. The majority of the work was a celebration of strength and skill, which the artists had in abundance. Highlights included Suzie Langford’s Cloud Swing routine Tokyo Clouds. Compared to the trapeze this apparatus allows for a gentler physical gesture, making Langford’s death-defying free falls all the more surprising and breathtaking. Susan Mitchell performed an invigorating web spinning routine, Kamikaze, with great strength and precision, and the Urban Spin duo between Langford and Mitchell showed a maturity in their skills and performance presence-they make a good team. Under the Sea, performed by Shelalagh McGovern, was an elegant and gutsy swinging trapeze routine with heart-stopping drops to foot hangs at peak swing, accompanied by guitarist Antonio Dixon and blues singer Mari-Jon Berna, who has one of the most soul-satisfying voices around.

Fortunately, a few of the pieces attempted to push through the showy style that inevitably arises from apparatus and skill-oriented work. Bernard Bru’s Sakura was based around a well developed clown persona and involved an elaborate routine of innovative climbs to the ceiling to release a gentle flow of sand-perhaps a meditation on time and Zen. Playing with the gestural translations of cartoons like Astro Boy, Meika Kiven and Charmaine Piggott pushed the regular trapeze tricks-half angel, foot hang, one armed hang-into refreshingly new shapes and constructions creating an integrated relationship between apparatus and performer. In contrast, Hiroshima by Genevieve Moran, with text by John Hersy, though elegantly performed, did not create a significant connection nor juxtaposition between the physicality of standard ‘tricks’ performed on the lyre (hanging hoop) and the text-one of the difficulties to be worked through when pushing physical performance into more narrative ground.

The most interesting work for me was Simple Terms. Catherine Daniel appeared on stage in simple day wear (no glitter to be seen), looking for her partner. Casually she ran through her complex routine on silks, chatting to the audience, flirting with a boy in the audience. Eventually Jessica Paff arrived and they performed a sophisticated, though still casual routine, on the one silk, continuing the conversation. The underplayed, anti-theatrical nature of the this work was refreshing and suggested a different conceptualisation of aerial performance. I hope they continue investigations in this style.

Big in Japan was a celebration of skill more than of Asian cultural influences. Many of the references were slight, a red sun Tshirt here, a kimono there, which considering the enormous influence of Asian performance training systems (Suzuki, Butoh, Bodyweather) on Australian contemporary performance seemed a little naive. Now that the skills are there and developing, it would be great to see an increased engagement with material on deeper and more conceptual levels-admittedly difficult in such a tricks based medium but something to strive for as Aerialize continue training Sydney performers to swoop, dive and fly.

Big in Japan, Aerialize- Sydney Aerial Theatre, Aug 29-Sept1, Newtown Theatre, Sydney.

RealTime issue #51 Oct-Nov 2002 pg. web

© Gail Priest; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

A broken tree, each segment labelled with a number. Standing among them Koon Fei Wong silently accounts for each piece on her air calculator. Pale and willowy in little girl dress, the performer is nevertheless powerfully present. Plagued by nightmares, trauma of collective memories, she strives to embody her visions in fragments of language and gesture. The tiniest of wrist actions takes our attention, it animates an arm that floats out from the torso. From the side of the stage Liberty Kerr on cello and Barbara Clare sampling sounds, underscore or interrupt with their own murmuring utterances. Images spill onto the stage. A pile of bodies, dead arms reaching out to be held. Fei chops at her arm, repeats “Long or short sleeves? Or sleeveless?” She stands on a dismembered trunk, “I’m great. I’m terrific.” A proud little smile dances on her lips, in the corners of her eyes, while those same muscles reveal the lie. She speaks of bloodied bones in snow, the colour moving between elements, red to white to brown. In the elusive way of dreams, events drift apart from physical sensation. Remembering her child self as helpless witness to violence, she detachedly describes events in voiceover. Meanwhile her naked body grasps at the sensation in ineffectual movement, shuffling awkwardly on her buttocks from one side of the stage to the other. Finally she falls and falls and falls. And exhausted, she re-assembles the strewn fragments of the tree.

Koon Fei Wong came to Australia from Hong Kong 5 years ago to study Aeronautical Engineering. Thankfully, she lost her way and wound up at the School of Theatre Film and Dance at the University of NSW. Fei was also a participant in Tess de Quincey’s Triple Alice project in Central Australia, a profound experience which triggered some of the thoughts on dislocation and identity she explores so powerfully in this performance.

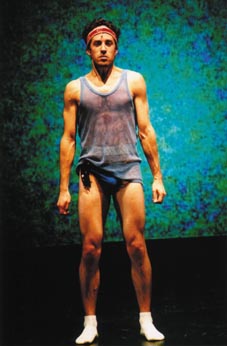

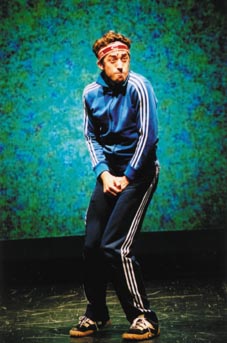

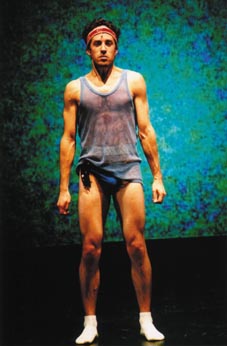

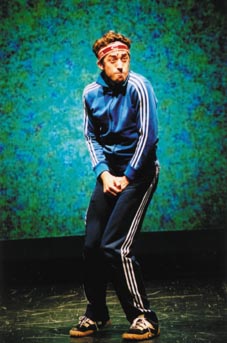

Teik Kim Pok in generic T, BVDs and white crew socks ponders his place on the map of cultural identity. Whether in Singapore or Australia, clearly being Teik Kim is not enough…”In a past life, I may have yelled ‘Long Live Chairman!’ Today I yell, ‘Long Live (fill in name of Western popstar)’.” And why have his parents only ever called him Daniel, a moniker officially registered nowhere? Taking stock of his upbringing and its effect Teik Kim tosses round possible identities, re-modelling himself, parading for us on a black and white runway. It’s a nicely judged performance, a blend of seriousness and fun that keeps the audience guessing. Along the way, he asks us to take a look at each other, to shake hands while resising eye contact. Finally uncomfortable in the suit, he discards it for a clearer match for his cultural confusions, where else but in the enigmatic persona of Michael Jackson-the black man who could pass for white, maker of his own idiosyncratic moves. Teik Kim flicks the switch to vaudeville and at last, utterly convincing to himself and his audience, with jutting pelvis, single glove, hat concealing features, he slides a slippery moonwalk to “Billy Jean.”

These 2 impressive short works were created as part of Teik Kim Pok’s and Koon Fei Wong’s research as Honours students in the School of Theatre Film and Dance at University of NSW. Both have also engaged with the contemporary performance community in Sydney for the last 2 years with earlier works seen at PACT Youth Theatre, Urban Theatre Projects, Performance Space and Belvoir Street.

Dis(re)membered, performer Koon Fei Wong, sound liberty & bc from magnusmusic, project supervisor Clare Grant; Post-Op Chamber Piece, performer Teik Kim Pok, sound Michelle Outram; Io Myers Theatre, September 25-28.

RealTime issue #51 Oct-Nov 2002 pg.

© Virginia Baxter; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Akram Khan

The paucity of international contemporary dance companies touring to Australia (a handful at arts festivals aside) was brought home by the visit from the UK of the Akram Khan Company and the excitement and dialogue it generated. The company was also resident at the University of Western Sydney and presented different programs at the Sydney Opera House and Brisbane’s Powerhouse.

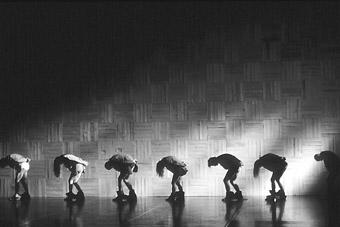

In her handy summation of Khan’s career and philosophy, “Clarity within chaos” (Dance Theatre Journal, Vol 18, No 1, 2002), Preeti Vasudevan reports that the 28 year-old Khan was born in South London into the Bengali community there, dancing from 3 years of age and beginning with kathak, classical dance from northern India and Pakistan, at the age of 7. At 21 he decided to train in contemporary dance and, subsequently to work at its integration with kathak. Khan says in the interview, “What I’m exploring is kathak, the dynamics and energies of kathak. It is kathak that informs the contemporary.” He conceptualises this classical dance as clarity and contemporary dance as chaotic-not in a sense of formlessness, but, somewhat akin to Chaos Theory, in terms of the invisibility of its borders. “It is an unfortunate misconception that [contemporary dance] has no boundaries. the difference is that you cannot see them…[but] you know [they] are there…”

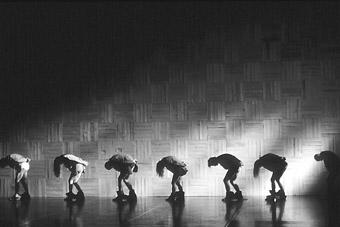

Khan continues to perform kathak in the UK and India, but his fame has primarily emerged from the contemporary work with his company, a powerful perpetual motion motor whose collective speed reminded me of nothing less than the minimalism of Steve Reich and Philip Glass-with their enormous, continuous flow of notes that for all the rapidity of their playing conveys a transcendent, subtle shifting of states. There are significant changes of pace and form in the 3 sections of Kaash (the 2002 work presented in Sydney), but the overall impression is of a mesmeric totality incorporating intense solo moments (Khan, reciting and demonstrating movement instructions from kathak focused on its gestural vocabulary) and remarkable collective harmony (a precision rarely seen in this country). From within this flow, which like Chaos Theory’s companion Complexity suggests a system working at optimum but ever on the edge, come strikingly memorable moments as dancers rapidly traverse the stage, spin and come to a sudden, curiously unabrupt halt, a sheer stillness, or, a little later, with the rhythms of the movement still in their bodies, an almost indiscernable rocking.

The contemplative blend of unleashed energy and overarching form is embodied too in Nitin Sawhney’s musical composition for Kaash. The dance corresponds closely to its rhythms, ecstatically in the bursts of tabla-driven propulsion. The viscerality of the percussion is layered with sustained notes sounding like they have been scraped from the edges of small gongs and cymbals, sometimes reverberating in harmony with the pulsing, barely stilled bodies of the dancers. It’s a composition that, like the dance, fuses the classical and the contemporary with confident ease.

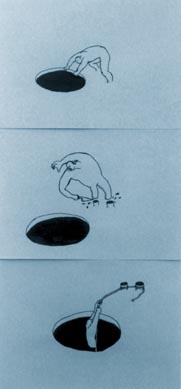

The context for Kaash is an open performing space forward of a huge work of art by Anish Kapoor-a painting of a framed, huge black hole. In the Kapoor manner it’s often difficult to see where this emptiness begins, the line between presence and absence constantly shifting and blurring, a state amplified by transformations of colour and density wrought by a superb lighting design.

This is no mere backdrop. Not only does it provide a parallel to the shifting energies of the dance, but it also reflects the thematic preoccupations of the choreography. Khann says, “‘Kaash’ means ‘if’ and I am basing it on the concept of Shiva. Shiva in Hindu religion is the destroyer and restorer of order. Shiva in Hebrew means the number 7. Seven is close to the rhythm and music modes of Indian classical that works with energy…What if you put a dancer in an ice cube and then the energy is released when the cube melts? That’s what Shiva is about” (Vasudevan).

Nor is Kapoor’s painting ignored by the dancers. In a work that is otherwise highly formalised the opening and closing moments of Kaash have the kind of abstract theatricality you’d expect from Saburo Tehsigawa. We arrive in the theatre to find a performer gazing into Kapoor’s creation, in turn therefore directing our own gaze, initiating the contemplation that follows. At the end of the performance one of the dancers becomes totally preoccupied with this vast, beautiful but disturbing portrait of sheer flatness and depth, his body swaying left to right, almost as if to fall, to be caught by his comrades in this dangerous reverie. Blackout.

I hope that this visit will inspire a producer or an arts festival director to bring the company to Australia again; in the meantime we can only be grateful to the Sydney Opera House, the Brisbane Powerhouse and the British Council for giving us a rare glimpse of a work of bracing and contemplative totality and cultural resonance.

Akram Khan Company, Kaash, The Drama Theatre, Sydney Opera House, Aug 20-24

RealTime issue #51 Oct-Nov 2002 pg. web

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

“I ain’t goin’ bionic!”

( Chuck D)

Fiona Cameron has for some time been one of the most striking presences within Chunky Move, her tall, statuesque pose breaking down into low, complicated, interwoven positions with disarming ease. She has produced several of her own works, notably Looking For a Life Cure (2001), in which she explored the near schizophrenic internalisation of contradictory states within modern life. Her latest project is a pair of duets dealing with urban alienation and the distance between individuals, performed at various informal locations (indoors and outdoors) within Melbourne.

As always with these much in demand dancers, Cameron and partner Carlee Mellow move with such elegance, poise and confidence(as well as with a touch of self-deprecating humour(that their merest physical inflection is eminently satisfying. Cameron is all jagged discomfort to Mellow’s absent-mindedly musing traveller, the knots they tie each other up in taking on a mood of accidental combat. Composer Luke Smiles adds a sense of sonic complexity, jumping from hip-hop loops to hyped techno flourishes, as well as more abstract digital fields and soundscapes (horns, motors, coffee-machines; a cacophony of urban samples).

The dance itself is somewhat slight both in terms of overt content and choreography. It is predominantly the performers’ dramatic nuances that bring it to life. The first piece is an extended joke of how when one is on public transport, one can end up with one’s foot over the ear of a neighbour, despite one’s best efforts to avoid physical proximity. This is a fun little dramatic sketch, but that is all.

The second dance is more provocative, depicting Cameron as a city dweller who has learnt the physical regimes and moves one must go through to avoid chance encounters. To draw on Public Enemy’s hip-hop terminology, Cameron’s character has been rendered “niggatronic,” or robotised in body and psyche (if not race, given that Cameron is white). Like break-dancers, her character moves to the subliminal beat of contemporary, urban capitalism(yet unlike B-boyz, her character (as opposed to Cameron the choreographer) does not consciously manipulate these movements and feelings so as to dramatise her condition. Mellow by contrast seems to follow John Cage’s exhortation to consciously react to the random sounds and textures which surround one in urban life. Not so much stopping to smell the daisies, she pauses to hear the music of the city and pay attention to the other individuals who move throughout it.

Cameron’s dance-theatre scenario of 2 movers who respond very differently to the barrage of Smiles’ sounds encourages such reflections(particularly for those familiar with hip-hop preachers like Chuck D or Kodwo Eshun. It is nevertheless an uncomplicated work in itself, depicting a simple exchange between the characters leading to a comic resolution in which Mellow leaves Cameron reluctantly holding the hands of 2 co-opted spectators. The production was disappointing in the limited way it interacted with or was consciously situated within the spaces it was staged(beyond dealing with the broad theme of urbanity. Overall Inhabited was a thoroughly enjoyable, interesting, short performance which nevertheless did not amount to anything substantial. One hopes therefore that this curious divertissement represents a taster for more impressive full-length works to follow.

“I ain’t goin’ niggatronic; smart enough to know that I ain’t bionic.”

Chuck D, from Public Enemy, Muse Sick-N-Hour Mess Age (NY, Def Jam, 1994)

Inhabited, director/choreographer/performer Fiona Cameron, performer/co-choreographer Carlee Mellow, co-choreographer Nicole Johnston, music Luke Smiles. Various locations, Melbourne, Aug 2 -Sept 1

RealTime issue #51 Oct-Nov 2002 pg. web

© Jonathan Marshall; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

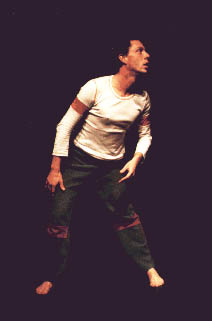

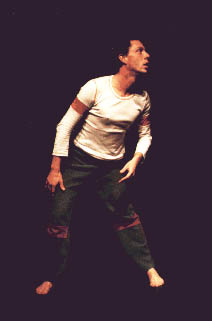

Phillip Adams’ Amplification (1999) was an intensely focused study of damaged physicality and desire. His new work, Endling, however is stylistically closer to Adams’ Upholster (2001), employing a jump-cut, mixmaster approach to develop something akin to an absurdist opera. Musical references identify which aesthetic tropes are evoked and assaulted in each of Adams’ scenarios: bucolic neo-classicism for ballet, Modernist dissonance for empty angst, Ligeti for 2001-style fantasies of rebirth.

Adams treats culture and art history as a bazaar, plundering them for ironic details and unlikely, kitsch amalgams. While Upholster is ultimately little more than a choreographically-complicated, funny and sexy divertissement, leaping from the Karma sutra to furniture upholstery, the grab-bag historicism of Endling charts a more coherent and thought-provoking path through the detritus of high and low culture.

Thematically, Endling deals with issues of animality, with the dancers both applying anthropomorphisms to the biological elements they engage with (a fox stole looks back, quizzically, at Stephanie Lake after a brief, sexualised encounter) as well as becoming animal themselves. The early section has an almost hysterical energy, flinging bodies rushing from one scenario to another with a pathological illogicality reminiscent of Lake’s own Love is the Cause (2001). This explosion of themes and movement soon stabilises into a more measured approach however, with Adams increasingly framing and posing his events into lightly moving tableaux.

The comic bizarreness of Endling had me thinking of Grand Union dance theatre or ‘the World’s First Ever Pose-Band’ from the 1970s. Adams has remained close to a maniacally Pop-art sensibility. The Pop reference is also significant in that the humour he develops, while strong, comes from a sense of irony more akin to Warhol’s flat persona than the Chunky Move productions he and several of his dancers have worked on. This is intensely serious play, the characters attempting new rituals for a world where animality-whatever it may signify-is at best attenuated and difficult to encounter. The performers stretch out a massive cowhide between them like a trampoline and rearrange glass-eyed fur wraps upon it, as though testing a form of neo-paganism-but like everything else in Endling (as opposed toAmplification) no desire, satisfaction or ‘primal force’ is evoked. These are rituals which fail to produce a religion. Like Adams’ own approach to culture, the characters of his drama burrow through material without settling anywhere.

Endling can therefore be read as a critique of Martha Graham’s primitivist works such as Into the Labyrinth. Unlike Graham (or even Stephen Page in reappropriating Graham devices), Adams is not suggesting that references such as bullfighting allow us access to a primitive, pre-civilised state. Animality is finally seen as nothing more than a mirror held up to humanity, a projection of human concerns, and not “Nature untamed.” For Adams’ characters, to be animal metaphoricises social marginality, sexuality, or (in a lingering duet between Byron Perry and Toby Mills) homoeroticism. Ultimately the stuffed animals the dancers play with, or the projected footage of the last Tasmanian tiger, preserve a distance from both performer and audience, remaining objects which play in our (human) imagination.

Balletlab, Endling ‘Self-Encasing’ Trilogy: Part #1, choreographer Phillip Adams, primary design Sally Smart, lighting Paul Jackson; performers Michelle Heaven, Stephanie Lake, Toby Mills, Byron Perry, Brook Stamp, Joanne White. Dancehouse: Balletlab, company-in-residence, Melbourne, June 12-16.

RealTime issue #51 Oct-Nov 2002 pg. web

© Jonathan Marshall; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Rebecca Ewer, The Gallery #2, 2001, c-type photograph

The setting is familiar and so are the people. Someone fills your wineglass and asks if you’re having a good time. Faces you recognise stop and say hello, while new acquaintances smile as they pass by. You even look at the art every now and then (just to remind yourself why you’re there). We expect it all to mean something but it rarely ever does.

Memories create the basis for illusion and constructed landscapes offer limitless possibilities. Nothing is ever as it seems in the photographs of Rebecca Ewer. Closer inspection will reveal the truth. Simple scenes are sometimes just that, but reality is always open to interpretation. Watch this space.

Works from Ewer’s The Gallery series have recently been shown in the 5UV window and Adelaide Central Gallery.

RealTime issue #51 Oct-Nov 2002 pg.

© Leanne Amodeo; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

The phenomenal growth of communication systems promotes somewhat idealistically the view that geographical and social boundaries are dissolving. However, negotiating interpersonal relationships is still fraught with miscommunication. Contemporary existence relies upon disentangling systems of social, historical, political and personal bias and can leave us subject to preconceptions and psychological instabilities. It is the fragile dynamics of human interaction that tends to undermine our conscientious desire to get along, leaving us, potentially, a bit myopic.

At times then, it seems necessary to adopt a particular viewpoint and defend it and Ricardo Fernendes, writing in the exhibition catalogue on the work of Singaporean artist Mathew Ngui, acknowledges that this can have a polarizing effect. He states: “Everyone chooses his position, be it conniving or rebelling.” The slipperiness and fallibility of systems of communication is demonstrated in Ngui’s cleverly devised installation in Adelaide’s Contemporary Art Centre. As in previous works it is layered with complex metaphors for human activity and the subjectivity of perception.

Precisely planned out in its choreography of materials, Ngui’s installation uses technological devices to negotiate and invert perceptions of the real. Two video cameras on tripods at opposite ends of the room are trained on a forest of PVC pipes inscribed with hand-painted and unintelligible markings. Innocuous looking scraps of timber are placed against one wall and along the gallery floor. When the viewer looks through the video eyepiece the forest of pipes appears as a flat wall and the markings form into a coherent text describing the action of sitting upon a chair. When viewed from a precise vantage point the apparently random bits of wood suddenly coalesce into a chair or rather a perspective ‘drawing’ of a chair in space.

In an empty gallery the PVC and text are coolly totemic. However the static image through the eyepiece is interrupted when visitors pass between the pipes as they navigate their way through the room. This destabilizing of perception is further heightened when the viewer moves to the back room. Here, the relayed wall of text, together with taped sounds from the video cameras, is now projected directly onto the gallery wall. In a performance video Ngui observes, interacts with, and seats himself upon the representation of the chair as seen in the first room. Under surveillance, the viewer has participated unknowingly in the work and becomes an integral part of it.

Multiplying possible viewpoints through the use of multisensory devices and strategically placed clues, Ngui reminds us that reality is a construct, subject to flux and interpretation. Electrical conduits and PVC piping suggest systems of conveyance but interpretation of the objects requires a willingness to ‘see’ beyond the obvious. The viewer is led by recognition and misrecognition of vision, sound and text to investigate the ‘logic’ of spatial and social realms. Trompe-l’oeil illusionism provokes shifts in pictorial space by introducing ambiguous imagery that appears to fluctuate from the real to fictive. Ngui’s work provides metaphors for the perception of multiple physical realities and provides a parallel invitation to explore the complexity of the emotional realm. The transmission of the personal and the emotional are equally susceptible to misinterpretation. Fernendes underlines this emotional capacity in the exhibition catalogue stating, “It is an open space for poetic, logical and metaphysical interventions.”

Mathew Ngui, Tell Me Where I Stand, Contemporary Art Centre of South Australi , July 12-Aug 11

RealTime issue #51 Oct-Nov 2002 pg. web

© Katrina Simmons; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

At a LaBasta! gig, someone is deliberately butchering Beckett’s Waiting For Godot with her ultra-dry, self-interrupted delivery. Before the shadow puppets come out, someone else forces a What Is Music? flier into my fist. What Is Music? When is that? Somehow, I get to an under-promoted, but nevertheless packed gig at an old, rock’n’roll pub. Toshimaru Nakamura’s superb No-input mixing board CD is ringing in my ears.

W.I.M? festival co-director Rob Avenaim is first up, making scratchy noises and false-foley work. It reminds me of Pauline Oliveros’ latest CD (In The Arms of Reynolds, Lowlands Distribution, Belgium), but not as good. He drapes his long hair off stage to be replaced by Tetuzi Akiyama, who takes a metal bow with custom microphone pickups on either end to a static acoustic guitar and begins to saw. Zzzz, zzzz. Wow. It all builds to this high-pitched nastiness as he provokes things with his free hand, holding blunt knives and plastic brushes. Almost too many (dis)harmonies. Luv those Japanese minimalists.

Next up is Julian Knowles, having a subdued, fun time behind his laptop—dull to look at, great to listen to. He takes us on a wild ride, from the gritty atmospheres of contemporary digital soundscapes (what would we do without Pro Tools?), then sheets of aggressive, sparkling, scintillating neo-electroacoustics, asymmetrically off-the-beat drum’n’bass, fluttering bass-drones, and more. I haven’t heard such a stylistically expansive palette since Battery Operated toured.

The big deal of the night is up next. I’m not keen. I’m not an Oren Ambarchi fan, his guitar hum is too damn quiet. Same problem with digi-man Phil Samartzis. They’re joined by Günter Müller, who, by rubbing 2 microphones together, or skimming them across cymbals, kicks up quite a din right from the start. Ambarchi and Samartzis respond in kind. Did I just see Ambarchi play an actual note? His guitar sounds particularly dark tonight, ghosting the styles of his peers, while deep, resonant hums emerge from Müller, and Samartzis caps it off with loud, crinkly, micro-exclamations. I remember Pierre Schaeffer’s statement of composing for “the astonished ear.” Well, my ear’s feeling pretty astonished.

After that unexpected delight, Nakamura takes ages to set up. A technical problem? We never know, but an icy draft in the pub is making the audience decidedly restive. When he finally plays, he proves disappointing. Sure, it has a rough aggression lacking in his CDs, a playful expressiveness, but these short phrases seem a bit like pointless noodling. Where are the exquisite, ringing loops captured on CD (No-input mixing board, Tokyo: Zero Gravity, 2000)?

My blood is slowing to ice as the last act, Voicecrack, set up, in the middle of the room, a table covered in cheap electronic doohickies: toys, bike-lights, clapped out scanners, and a heap of photoelectric contraptions. In near darkness they start manipulating the number, intensity and periodicity of light sources flickering onto the light-sensitive devices. A huge wall of industrial noise emerges; the kind of sound that would make Merzbow proud. The Swiss duo’s work fits well into Nietzche’s Germanic ideas about Dionysian chaos uniting life and death. I listen for 20 minutes, but their annihilating sound hasn’t warmed up the pub. I scatter for home before I turn into a pillar of salty ice.

What Is Music?, Corner Hotel, July 16; Waiting for Godot, versioned by LaBasta!, Meyers Place Bar, July 7.

RealTime issue #51 Oct-Nov 2002 pg. web

© Jonathan Marshall; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

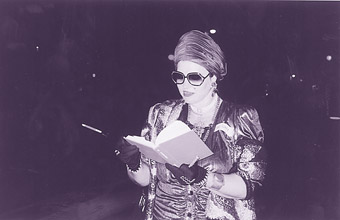

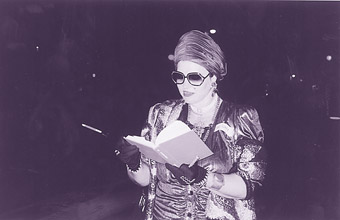

It is opening night at the Schauspielhaus in Vienna’s 9th district. The foyer is packed with vibrant yet reserved Viennese for the second season of Paul Capsis’ Boulevard Delirium. Viennese are a very diligent theatre going lot with the city boasting 45 theatres for a population of 1.7 million. There is no need for programs to develop new audiences or to attract young people—it is a core aspect of a culture that has spawned the likes of Mozart, Strauss and Klimt to mention but a few. The minister for culture, who was in attendance on opening night, is the third most powerful man in Austrian politics. It is not surprising that one of Australia’s most challenging and talented directors Barrie Kosky has taken up residence there as the director. With an annual budget of just under 3 million (AUD), a core staff of 10, a box office income expectation of just 5% and 3 month rehearsal periods he says it’s like a dream come true.

The house lights dim and Capsis appears spot lit in front of a lush red velvet curtain, his burlesque character in total harmony with the theatre’s historic ambience. Top hatted and tailed, he launches into a sumptuous rendition of 'Windmills of My Mind' which segues seamlessly into the wrenching 60s classic 'Anyone Who had a Heart.' The audience is transfixed.

From this intimacy the curtains part to reveal the full complement of the musical ensemble. Capsis is in his element, he is singing the blues-and how! The songs are raunchy, and the Viennese bristle. Relief comes climactically through the heartfelt ballad 'Little Girl Blue'. Capsis then evokes Garland and we are her audience in Carnegie Hall. Kosky’s delicate orchestration allows us an intimate insight into this vulnerable persona. Through classic standards such as ‘The Man that Got Away' and 'Get Happy', Capsis is able not only to interpret Garland but also to add layers through his unique renditions, from pop to punk and back again.

The Viennese swoon to Marlene’s appearance in their native tongue, only to be caught off guard by a strident Streisand attacking them with 'Don’t Rain on My Parade.' And before our next breath, we are praising the lord in a fervor of gospel evangelism.

With a twist of his hair and the placing of a flower, Billy Holiday makes her entrance. Close your eyes and the similarity is remarkable, the characterization sublime.

A Capsis show is never complete without Janis hitting the stage; her reckless hair and loose presence throw us into a free love euphoric Woodstock affair. The audience go ballistic. Capsis and Kosky cleverly exploit this dynamic by catapulting us into a sensational version of Queen’s 'We are the Champions', the poignancy of the rock ‘anthem’ touched the heart and soul of the audience. Capsis exits leaving us chanting for more. We are appeased by a beautifully stark rendition of 'Summertime' before he concludes with the edgy and provocative 'Home Is Where the Hatred Is.'

Broadway Delirium is the culmination of the Capsis experience, combining his favorite characters over the years in a fresh interpretation. Kosky’s clever staging, lighting and direction create a richly dramatic journey, the essence of which lies in the brilliant placement of songs. Backed by a very agile and tight band led by musical director Roman Gottwald, the electric combination of Kosky and Capsis results in a dangerously sophisticated and stylized cabaret. The Viennese loved it.

Paul Capsis, Boulevard Delirium, director Barrie Kosky, musical director Roman Gottwald, Schauspielhaus, Vienna, Sept 6.

RealTime issue #51 Oct-Nov 2002 pg. web

© Alex Galeazzi & Panos Couros; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

I refer to Solrun Hoaas’ “An Australian Blindspot “ in RealTime 50. As the Festival Programmer for REAL:life on film I feel it is important to respond to some of the criticisms raised by Hoaas in relation to the dearth of Asian programming at this year’s festival.

Since its inception in 1999, REAL:life has attempted to redress the balance of anglo-centric programming within the Australian screen culture industry with a culturally diverse program of documentary films in terms of origin, content and style. While I agree that documentaries from the Asian region did not adequately feature at this year’s festival this was by no means due to a disregard for the promotion of the cultural, social, political or personal issues represented through Asian documentary or the styles and sensibilities of Asian cinema. This was, in actual fact, a result of the limited submissions received from Asian filmmakers both internationally and locally.

Out of the 10 international titles that screened at this year’s festival, REAL:life featured documentaries from the USA, UK, Japan, Iran, Romania and France. While most of these films were co-productions with UK or USA-based filmmakers it is important to note that over the past 3 years REAL:life has showcased documentaries from all over the globe including India, Israel, Lebanon, China, Slovenia, Ethiopia, Slovakia, Poland, Lithuania, Taiwan, Cuba, Egypt and many more. The 13 Australian titles selected to screen in 2003 featured culturally diverse stories from the parochial to the international. A number of these addressed issues within the region including the aftermath of the East Timor declaration of independence, the impact of the 1984 Indian Sikh riots on an Indian-Australian family and Korean-American cross cultural identity.

With the growth of the festival, greater resources and better access to international titles, REAL:life looks forward to featuring more Asian documentaries and is currently researching potential titles for inclusion at the next festival.

Kind Regards,

Natasha Gadd,

Festival Programmer REAL: life on film

RealTime issue #51 Oct-Nov 2002 pg.

© Natasha Gadd; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

A focus on the performance of “contemporary classical” or any other kind of current music is not something one generally associates with the major music schools in Australia, some of which still use the label “Conservatorium” to describe themselves. This term implies an agenda of conserving the repertoire of western classical music, principally of the 18th and 19th centuries. Noble as this aim is, the contemporary reality means new approaches to preparing music professionals are being sought across the sector. Professor Nicolette Fraillon, Director of the Canberra School of Music (and now the newly appointed Music Director and Chief Conductor of the Australian Ballet) notes that because “traditional performance jobs are still being reduced in terms of funding and the sizes of orchestras, (graduates) need to be really prepared and creative in a variety of ways in order to support themselves.”

The traditional preparation of a classical music performer is a long and rigorous process. It requires considerably more dedication if you add the skills associated with a variety of contemporary music practices such as the ability to play complex rhythms, to use non-traditional techniques and music technology, to improvise and even to engage with movement and acting. Musical genres are constantly blurring and mutating so it is difficult to know what approach can be adopted to provide the best kind of grounding for the modern musician.

The traditional music school has been forced to reconsider its offerings as the contemporary musical landscape has changed and the relevance of music degrees has come into question from the wider music industry. At the core of the problem is the traditional curriculum. According to Dr Tony Gould, Head of the School of Music at the Victorian College of the Arts (VCA), “the curriculum hasn’t changed much since I was a student more than 30 years ago.” In the same period, however, the repertoire and required skills have expanded greatly. Gould questions the deeply held notion in the Conservatorium culture that one has to have mastered Mozart and Beethoven before attempting the contemporary repertoire. Stephen Whittington, Senior Lecturer at the Elder School of Music in Adelaide, also believes the curriculum needs to be more flexible and that more interaction should formally occur between the various streams in a typical music school (eg composition, music technology, classical music performance and jazz performance), streams that have been traditionally segregated from one another. For Whittington the undergraduate curriculum is full of subjects that music academics steadfastly believe are core requirements for training a musician. Consequently there is no room to add new subjects such as multimedia as they come into the picture. Whittington asks: “Can you do multimedia if you can’t write a fugue?” The answer is obvious, but the reluctance to let go of archaic fields of study still represents a stumbling block in curriculum reform.

One modernisation strategy gaining momentum is the incorporation of compulsory improvisation training for all students at undergraduate level. Queensland Conservatorium and the University of Western Sydney (UWS) have done this already and, according to Professor Sharman Pretty, the Sydney Conservatorium of Music is poised to follow. Pretty explains that this will be one of the likely outcomes of a large development project at the Sydney Conservatorium in the field of “performance and communication”, a project that “aims to find ways for mainstream classical musicians to break out of the mould and to interface better with the broader community.”

Major music schools have always had to balance their focus of training elite musicians with providing a general training and performance service to the community, but in the current climate the need seems more pressing than ever. A greater responsiveness to the music industry and to other industries being served is also an urgent matter.

For example, Professor Robert Constable at Newcastle Conservatorium reports that there has been demand from the students doing the Church Music strand of the Bachelor of Music degree to incorporate contemporary gospel composition and performance training into the curriculum. Newcastle Conservatorium has also successfully introduced a suite of online postgraduate music technology courses that have mostly attracted school teachers seeking to upgrade their professional skills.

It has perhaps been easier for the small music schools to take a more radical approach to the problem of the contemporary relevance of their courses. At Southern Cross University in Lismore NSW we have completely broken with the classical music tradition in favour of training musicians and audio engineers for the contemporary popular music industry. In this specialist area there is arguably even more pressure to remain relevant to the industry, so we constantly struggle with the appearances of new musical genres and ever-advancing technologies. A few institutions, notably the Queensland University of Technology (QUT) and UWS have chosen to embrace the contemporary in a more global sense, combining a range of contemporary styles including the popular. According to QUT’s Associate Professor Andy Arthurs, “there is no one way to play or compose music.” Thus at QUT experimentalism and a diversity of contemporary stylistic performance and creative practices are encouraged. At UWS, Dr Jim Franklin describes a more radical approach insisting that students broaden their stylistic palette. If they come in as rock musicians, for example, they will be expected to engage also with a contrasting tradition such as classical performance, and vice versa. All performance students, even classical specialists, are also required to incorporate sound and/or visual technology into their performance exam projects in a substantial way.

Even within the conservatorium, mandatory engagement with the contemporary is a strategic option. At the VCA, Tony Gould is deeply committed to “correcting the balance between the old and the new.” However, in programming recent Australian works for all student orchestra concerts he expects significant opposition from conservative elements within the school.

In many senses the rise of computer music technology has changed the ball game forever for music schools. Most of the sounds now heard on radio, television and interactive multimedia are predominantly electronic. In much pop music, the only thing that isn’t electronic is the voice. In the nightclub scene people dance almost exclusively to electronic beats. So while the majority of music students are performers it is arguable that the most vital work being done in music schools is in the recording studios and computer workstation labs. Activities range from the production of audio and multimedia artworks to the invention of new methods of digital arts creation and manipulation. Traditional music schools such as the Sydney Conservatorium of Music and the Canberra School of Music have led the way in the creation of software instruments in Australia, and have been joined in recent years by QUT, UWS and a few others. There is understandably more activity in this area going on at postgraduate level where the curriculum is much more flexible.

Despite these advances in the modernisation of curriculum and research there are continual challenges as the technological revolution grinds on. Stephen Whittington notes that at the Elder School of Music there is a new type of composition student who is not concerned with live performance outcomes and often not competent in, or even interested in, music notation. Working with sound entirely in the digital domain is fast becoming the norm in creative music. Whereas a decade or two ago there was a concern that the so-called “musically illiterate” rock guitarist or drummer was not being catered for in the tertiary music education system, we are now faced with a new set of creative practices that bypass the performer altogether. Another anomaly is that no tertiary music institution seems to have seriously engaged with DJing. The DJ is arguably a performer and an improviser but it is difficult to envisage a performance major being created to cover this ubiquitous performance practice.

Although it is impossible to imagine that the music performer will disappear from the musical industry landscape, it is clear that a different breed of musician is likely to emerge who combines a broader range of performance techniques with skills in composition, communication, multimedia and niche marketing.

With the increasingly cross-disciplinary nature of contemporary arts practice, music and other single-artform schools and their host institutions are also being forced to confront their artform ghettoisation tendencies. There have been a number of ways forward including the trend to establish digital arts degrees in institutions that have both visual arts and music programs. This is more viable when the contributing disciplines are in the same location and when strategic decisions to focus on multi-arts and technology collaboration have been made. In recent times the most spectacular example of this phenomenon has been the formation of QUT’s Faculty of Creative Industries.

How music as a discipline fares in these cross-disciplinary conglomerates remains to be seen. At the core of music is live performance, whether it is a string quartet, a jazz ensemble, or a contemporary pop band. Maintaining the performance tradition in the face of the digital arts revolution will be one of the great challenges of music and music education in the future.

RealTime issue #50 Aug-Sept 2002 pg. 4

© Michael Hannan; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Ian Scott, Anne Browning, Slow Love

photo Jeff Busby

Ian Scott, Anne Browning, Slow Love

Writer Richard Murphet notes in his introduction to Quick Death (1981, in Performing the unNameable, Currency Press with RealTime, 1999) that where most scripts are concerned with “What is it about?” and “Why?” his work focuses “on those thrilling questions—When? and How?”

Slow Love could be seen as an Australian avant-garde classic, enjoying the rare privilege of entering its fourth staging. The text consists of a series of instructions which make up over 100 short, cinematically-framed, enigmatic scenes—mostly without words—which explore various romantic, erotic and affective permutations between 2 men and 2 women. For example, woman 1 sits on a bed and looks right before man 2 rises, topless, from the bed behind her. After blackout, this scene is repeated, but with man 1 walking in on them.

Murphet’s approach opens a rich vein of interpretive possibilities for both audiences and directors. The scenes hang in a dissociated realm where it becomes apparent that both the characters and the audience craft their lives from a limited number of possible actions and outcomes. Virtually all of the worlds sketched by Murphet have been scripted before in film, television and romantic literature.

Murphet’s strongest cinematographic reference is film noir. Chamber Made Opera director Douglas Horton describes the 1983 Anthill version, directed by Jean-Pierre Mignon, as having a “Bette Davis/African Queen” feel, while the cast of the Australian-Flemish co-production (director Boris Kelly; Belgium, Holland & 2002 Adelaide Festival) were clothed in chic, black garb. Horton however has consistently refused to stick closely to extant staging conventions (The Chairs, Teorema). Far from having film noir’s dark, sharply defined contrasts, this production is closer to the grubby, smudged pathos of Ken Loach films. The cast are dressed in drab, loose-fitting, down-market clothes, while the set is reminiscent of a building under demolition. Undressed, mismatched window frames are laced together to produce 2 open work rooms, while a squat, ugly, black wall defines the stage wings. The lighting too exudes lower-class dejection, yellowing mists filtering through, or garish red and blue spots stabbing out like at a cheap nightclub.

The effect is to remove Murphet’s treatment not only from its stylised origins, but also its stylish ones, placing the performance in a world of petty jealousies and fragmented, unsatisfying relationships. Where earlier productions tended to deflate social expectations of romance by the unremitting portrayal of its classy, fictional origins, Horton’s version is a portrait of sad characters whose gestures only barely manage to evoke such models as Davis and Bogart, against which their own lives are unfavourably compared. Murphet notes that where younger casts have played Slow Love as if the characters were beginning their journey into romance, these figures now seem jaded—in Murphet’s words, they are “haunted” by love and its fictional images.

The general grubbiness of the production is also enhanced by the use of cinesonic samples, with grabs from television advertising and other fragments screened onto semi-occluded, on-stage sets, or mulched-out in Stevie Wishart’s live electronic score. The music is indeed the most perplexing element of this production, the sound abruptly leaping from extended string-produced drones (which Wishart creates by reinventing the hurdy-gurdy as an angular, Steve-Reich-style, avant-garde instrument) to beat-heavy drum’n’bass (which seems rather inimical to characters’ moods and actions). Wishart’s score is highly engaging in its diverse palette (almost Enya-like vocals, Laurie-Anderson-style violin doodling, semi-improvised processed samples) but it seems pegged to the cumulative effect of Murphet’s text as a whole, rather than anything in the scenes themselves. The music therefore exists almost entirely parallel to the staging, instead of providing much in the way of keys or entries into the work, or even an overt sonic dialogue with the performance.

What is one to make then of this production overall? I myself was rather disappointed. Not having seen Murphet’s works in performance, I was expecting the sharp chiaroscuro of film noir, “played (as the introduction to Quick Death states) cleanly, clearly and accurately.” Horton and Wishart by contrast have deliberately muddied the look, feel and sound of this aesthetic. Nevertheless, by doing so they produce a work which, despite its drawbacks, demands careful attention to the slight, enigmatic nuances separating ‘natural’ performance from the highly evocative tendrils which link it to romantic fictions as venerable as the Renaissance serenades Wishart briefly drops into. Earlier, slicker takes on Murphet’s script may, in the long run, prove preferable. None of those associated with this production however are content to allow either this script or performance practice in general to remain static. I therefore put Slow Love down as a fabulously brilliant, challenging failure, and fervently look forward to more such works—successful or otherwise.

Chamber Made Opera, Slow Love, writer Richard Murphet, director Douglas Horton, music composition & performance Stevie Wishart, design Trina Parker, lighting David Murray, performers Anne Browning, Beth Child, Mark Pegler, Ian Scott. Malthouse, June 21-29

RealTime issue #50 Aug-Sept 2002 pg. 6

© Jonathan Marshall; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

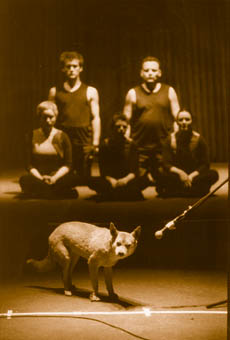

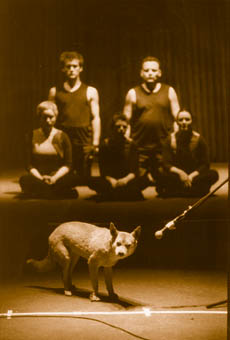

Rhonda Niemann, Matthew Dewey, Rachel Wenona, Ainslie Keele, Touch Wood

photo Bruce Miller

Rhonda Niemann, Matthew Dewey, Rachel Wenona, Ainslie Keele, Touch Wood

Recent productions by Hobart companies, IHOS’s Touch Wood and Scape Inc’s Who the Fuck is Erica Price (see review) while stylistically distinctive, shared certain concerns, notably human isolation, if not tragedy, and a non-judgmental view of aspects of mental instability. These bleak topics were countered by spellbindingly good productions, with nuanced performances bringing out the best in script and libretti.

Increasingly, IHOS Opera mentors younger performers through its Music Theatre Laboratory, presenting works-in-progress. These performances are arguably more successful than some of IHOS’s full-scale productions, several of which have been excessive in their attempts to incorporate every trick in the book. The Laboratory, says IHOS, is “a place of experiment, discovery and learning” that gives young Tasmanian performers and composers the opportunity to work with directors and composers of national and international renown.

The program begins with 3 short works, varied in musicality, style and content, but well suited for showcasing the potential of the performers. Butterflies Lost is inspired by a work-in-progress by writer Joe Bugden and is an evocative soundscape set in the Terezin ghetto, the way station to Auschwitz for Jewish artists. Recorded voiceovers include excerpts of Nazi propaganda. Five ragged children play in an elaborate, forbidding set that incorporates broken glass. There’s a strong sense of menace. This is a very moving, very visual work.

Allan Badalassi’s Harmony explores the human potential of healing, incorporating Baha’i prayer text and referencing recent hostilities in Afghanistan and Pakistan. The voices of a 10-person choir soar, their glorious harmonies amongst the highlights of the evening. Rosemary Austen’s Eden’s Bequest sets to music the poetry of Judy Grahn. Solo soprano Sarah Jones performs as a sort of Everywoman, singing a repetitive leitmotif with exquisite clarity and exhibiting a dancer’s physical expressivity. Three female actors represent the ages of woman, engaging in esoteric and symbolic mime and ritual.

The main work, Touch Wood, is a thorough success. Concept and direction are by prominent Finnish choreographer and director Juha Vanhakartano and its music is by Adelaide-based composer Claudio Pompili. Touch Wood is accessible without losing intellectual rigour and largely succeeds in being humorous without trivialising its subject, obsessive-compulsive disorder. It looks, as the program note says, “at the rituals and obsessions we create to maintain our sense of security and draws parallels between them and the superstitions of mediaeval times.” It asks whether we enjoy greater freedom nowadays or if it’s an illusion. Five characters play out their private compulsions and rituals, occasionally interacting in amusing or poignant ways. There are some well realised solos incorporating spoken word and movement. I found the hypochondriac, the religious fanatic and the “compulsive apologiser” particularly entertaining.

The set, lighting and costumes, reminiscent of German Expressionist cinema, are integral to the success of Touch Wood. The performance reaches a musical and dramatic peak with a clever group-choreographed “silly walk” around the stage. The climax is loud, tuneful and exuberant and seems to imply that the human spirit can overcome even impossible odds.

IHOS Music Theatre Laboratory, Touch Wood, Peacock Theatre, Salamanca Arts Centre, May 23-26

RealTime issue #50 Aug-Sept 2002 pg. 6

© Diana Klaosen; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

In one of the essays from the Liquid Architecture 3 National Sound Art Festival catalogue, Luisa Rausa uses the myth of Echo as a starting point for sonic arts. Echo was banished to a cave to pine for her visually-obsessed lover Narcissus, cursed to return the words of others until she became nothing but an insubstantial echo. Sound has long been associated with such absent-yet-present ghosts, an ideal that reached its height with the extruded tape effects and smudged, crinkly soundscapes of musique concrete.

Although Jeremy Collings and Robin Fox supplemented these venerable tools with contemporary electronic devices, their work strongly evoked this tradition, creating a dense soundscape worthy of Xenakis. Natasha Anderson added inventive, breathy sounds, ranging from incomplete vocalisations, to wind glancing off a flute or gentle recorder notes. These were stripped, banished and contorted by Fox and Collings. The metaphor of Echo or Plato’s cave, of incomplete calls and responses drifting into abstraction, seems apt.

The gritty, spacious soundscapes that are a signature of later, digital processes—what Darrin Verhagen calls “delicate instability”—also featured in the festival. Black Farm for example was a strangely evocative, abstract AV work in which George Stasjic offered garish, cartoon images of the heads of Afro-American vampires and sheep, the camera moving slowly in or out. This was accompanied by Tim Catlin’s open, humming, acoustic world, which, in his words “privileges sonic density, texture and movement.”

The festival overall, however, was notable for its diversity. Bruce Mowson for example has a technologically-dirty-sounding take on minimalism, looping simple, hissy sounds so that his drones become the aural equivalent of op-art. Aural perceptions generate changes in modulation and emphasis where none objectively exist. Mowson’s short festival offering may not have been his best, but it had the elegant simplicity which informs all of his work.