Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

The Hobart Fringe Festival was set up several summers ago as a means for performers and practitioners in the experimental and non-mainstream arts to gain greater exposure. Tasmania has a rich vein of talent, across all the arts, but rather too few opportunities for these talents to be showcased. This goes for the experimental arts in particular. The entire Fringe Festival functions on a lot of enthusiasm and goodwill and a limited budget. Happily, the organisers are able to bring together a variety of smaller arts events, some of which would be taking place in any case, giving them a wider profile by including them within the Fringe, which runs for 2 weekends and the intervening week.

One of the best resolved and most professional events within this year’s Fringe Festival was the Multimedia Mini-Festival, curated by local video and performance artist and musician Matt Warren. Warren, current recipient of a Samstag Scholarship, will soon undertake MFA studies in Canada. Over the past few years he has been very active, statewide, in presenting individual, collaborative and specially-commissioned innovative public arts events combining elements of performance, sound, video and installation.

With few film events currently being held on any regular basis in Tasmania, the Mini-Festival was a terrific opportunity for artist-exhibitors and audiences alike. We have only limited opportunities to study film and video making in any depth—and professional openings are rare—so the existence of an enthusiastic culture of film and video artmaking and appreciation is doubly impressive.

One of the highlights was Film & Video on the Fringe, a well balanced evening screening of short films and videos, by mostly local artists, held at the theatre at the Hobart School of Art. (At the School of Art itself, the popular and well equipped Video Department, run by highly regarded video artist and musician Leigh Hobba, has been for some time teetering on the brink of threatened closure, ill-advised and unpopular though such a move would be.)

The stand-out works included the video Where Sleeping Dogs Lay by Peter Creek, looking at the consequences of domestic violence. Its absorbing 2-hander dialogue format is jeopardised by a tacked-on bit of drama, designed (probably) to provide some visual variety and ‘action’, but not a total success. Tony Thorne’s amusing animation Serving Suggestion is a subversive piece about consumerism and physical stereotypes. Its humour is from the South Park bodily fluids and functions school of wit, but it manages to present its own, original take on this well-worn theme. The closing credits are amongst the most fascinating and well executed I’ve seen.

Prominent emerging local filmmaker Sean Byrne’s Love Buzz takes a familiar if far-fetched plot device and makes it fresh and credible. There is some interesting—and deliberately self-conscious—dialogue, marred, however, by the technical limitations of the soundtrack. Dianna Graf’s short (3 min) video-collage of still photographic images is a simple idea seductively brought to fruition. But perhaps the most engaging work is Matt Warren’s short video, Phonecall, another very simple concept actualised, in this case, into something Kafkaesque in its disturbing unreadability.

It is night and a pyjama-clad Warren has clearly been woken from sleep by the ringing phone. The audience then simply listens as he responds; warily, laconically, impatiently and so on, to whatever is on the other end of the phone (which is never revealed). Something a bit suspect seems to be being discussed, but we can never quite tell; nothing is spelt out or explained. As in a genuine phonecall, there is no concession made for eavesdroppers; we get this tantalising, one-sided conversation, a monologue in effect, delivered by Warren in exasperated tones that hit just the right subtle comic note. The work is at once cryptic (in its spoken content) and familiar (the scenario of being summoned to the phone at an inappropriate moment, or for an unwelcome encounter). A minor masterpiece of observation and commentary.

Another interesting festival event was the setting-up at Contemporary Art Services Tasmania of a small video/digital art space, to remain in place after the festival, with a changing program of high-tech work. For the Mini-Festival, this multimedia room presented interactives and a quicktime movie along with examples of websites, all by local artists. For artlovers less than familiar with new media, this engaging program was a good introduction to the web and to computer-generated and interactive works. It is pleasing that CAST has taken the initiative to provide permanent exhibition space for this popular artform which is rarely shown at commercial or major public galleries. In its main gallery, CAST featured a challenging group show, Transmission, with the high-tech arts represented by Matt Warren’s hypnotically atmospheric video, I Still Miss You, minimalist digital prints by Troy Ruffels and intriguing lenticular photography from Sarah Ryan.

Arc Up, a rave party featuring a multimedia presentation It felt like love (music and film projection by Stuart Thorne and Glenn Dickson, with animations by Mark Cornelius and ambient video by Matt Warren) completed the main Multimedia Mini-Festival, but a Super 8 Film Competition and the event Celluloid Wax, held at the quirky cabaret-style venue Mona Lisa’s, also helped ensure that media arts had a high profile as an important component of the Hobart Fringe Festival.

Festival curator Warren observes, “I jumped at the chance when I was asked to curate the multimedia segment of the 1999 Hobart Fringe Festival because it’s my area of expertise and I thought it would allow me to check out lots of new stuff I hadn’t seen before. This new work needs to be seen and a festival is the ideal way to draw attention to it. The Film and Video on the Fringe screening attracted a full house and the Mini-Festival at CAST had a steady stream of visitors, so I believe my area of the festival—like the Fringe overall—was a success.”

Despite the difficulties confronting new media in Tasmania, the outlook is encouraging: connoisseurs can look forward to the Australian Network for Art and Technology’s 2-week masterclass/seminar in new media curating and theory to be held in Hobart in April. A highlight will be the associated exhibition of work by up-and-coming Tasmanian multimedia artists curated by Leigh Hobba, for the Plimsoll Gallery at the Centre for the Arts.

Film and Video on the Fringe: The Fringe Multimedia Mini-Festival, curated by Matt Warren, various venues around Hobart, January 30 – February 7.

RealTime issue #30 April-May 1999 pg. 25

© Di Klaosen; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

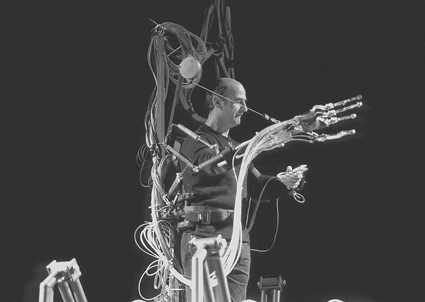

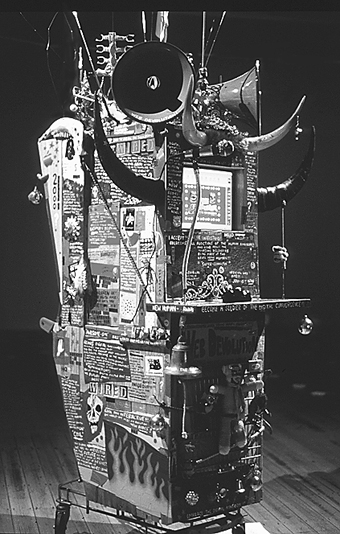

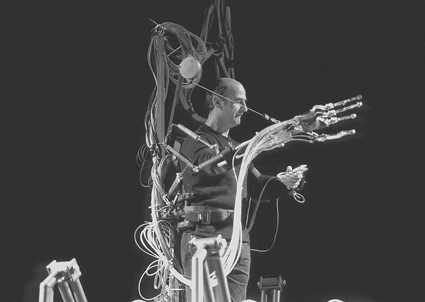

Stelarc and the exoskeleton

photo J. Haider

Stelarc and the exoskeleton

The laugh starts somewhere deep in the body and you can hear it on its journey through the chest and throat before it bursts out of the mouth of the artist like an alien creature. Then it vanishes and you wait for it to re-appear. The famous laugh of Stelarc has a life and reputation of its own, paralleling that of the artist himself. It seems natural enough but can he produce it at will? Is it the body’s natural expression surfacing or a performative behaviour designed to counter the expectations of a contemporary audience desiring outrage, extreme technical detail, physically dangerous actions and any of the other provocations associated with Stelarc’s work over the last 20 years. These questions of the performative are repeatedly raised in his work and they surfaced again at his presentation to the recent dLuxevent at the Museum of Sydney where Stelarc presented elements of his most recent work and offered the assembled a reading of it in his offhand, almost apologetic way (maybe it’s because he knows that the laugh is imminent…).

Despite such a distinctive laugh, Stelarc always depersonalises the experience of his body; he always refers to it as “The body” rather than “My body” and this is consistent with his sense of it as an organisation of structural components infused with intelligence, a smart machine. But what separates his thesis from, say the discourse of VW Kombi owners, is the idea that the body is not simply a vehicle to transport a disembodied consciousness through space/time. As Stelarc said, “We’ve always been these zombies behaving involuntarily” and this is partly why we have such endemic fears about the discourse of the body that his work opens up as it exposes the primal fear of the zombie, bodies animated by a distant alien intelligence (Descartes for example) in our imagining of the body and its function. On the other hand he raises the anxiety of the cyborg, for instance in his most recent explorations of the physical system in his Exoskeleton project which features “a pneumatically powered six-legged walking machine actuated by arm gestures.” The clumsy but alarmingly sudden movements of the machine compose the sounds it makes with those of the body into a kind of live soundtrack. This merging of the body’s sounds with those of the mechanical milieu into an ‘accompaniment’ to the performance is a signature element of Stelarc’s aesthetics in recent years and underscores his interest in the cybernetic potentials of art and behaviour.

One of the topics raised in the panel discussion (Chris Fleming, UTS; Jane Goodall, UWS; Vicki Kirby, UNSW; Gary Warner, CDP Media) following Stelarc’s presentation centred on the anxiety his work seems to provoke in audiences. Both the figure of the zombie and that of the cyborg disturb insofar as they seem to displace our sense of the humanistic self. Stelarc relentlessly pushes this concept to the margins and the space he opens in the field of body imaging and performance is breathtaking and a little scary for humanists because it is a field of future possibility and becoming rather than being and nostalgia.

Stelarc’s ideas were presented to his usual packed house—no doubt attributable to a combination of his appeal and the dLux organisational flair—who were shown video footage of recent and projected future work including Extra Ear. Much more will be said of this extremely controversial project which involves the ‘prosthetic augmentation’ of the human head (Stelarc’s) to fit another ear which could speak as well as listen by re-broadcasting audio signals, or just “whisper sweet nothings to the other ear” as Stelarc said so disarmingly. His other work-in-progress is the Movatar project which is an attempt to extend the use of digital avatars (virtual semi-autonomous bodies) to access the physical body (Stelarc’s) to perform actions in the real world. In this event, the body itself would become the prosthetic device. Yet none of this would be the same without the presence of the artist himself, with the big charming smile and booming laugh, animating a discussion which is sometimes too close to a tech-head’s wet dream. There is a necessary embodiment here of which Stelarc, as a performer, is acutely aware: “These ideas emanate from the performances. Anyone can come up with the ideas but unless you physically realise them and go through those experiences of new interfaces and new symbioses with technology and information, then it’s not interesting for me.” For Stelarc it is the task of physical actions to authenticate the ideas.

In her excellent and encyclopaedic study of contemporary performance art in Australia, Body and Self (OUP), Anne Marsh situates Stelarc in the recent history of the body in Australian performance in terms of a deconstructive journey from the opposition of body as truth/body as artefact, based on a dichotomy separating the natural from the cultural, to the place where these boundaries blur. From catharsis to abreactive process, from technophobia to the cyborg. In fact Stelarc is emblematic in this trajectory. Yet he has been widely misunderstood and misrecognised: as an uber shaman, who talks of the end of the organic body while performing elaborate rituals of pain and transgression of pain on the body in his 25 body suspension events (“with insertions into the skin”) of the 70s and 80s; a kind of electric butoh practitioner in his Fractal Flesh and Ping Body events; and more recently a “nervous Wizard of Oz strapped into the centre of a mass of wires and moving machinery.” (The Age, January 1 1999)

Stelarc has consistently challenged the way our culture has imagined the body, whether it is seen as a sacred object, a fetish of the natural, an organic unity…and the culture hasn’t always kept pace with him. Marsh’s book is also guilty of this as it attempts to situate Stelarc in terms of an enunciation of a particular subjectivity rather than reading it in its own terms. While Stelarc is certainly of the generation of major artists who have used the body as the work of art itself (Jill Orr, Mike Parr), manipulated it as an artefact rather than as a biological given (and therefore a kind of destiny) he is more concerned with the cybernetic body than with subjectivity, and more involved with pluralising and problematising the ways we speak of bodies and imagine them, and how we get them to do things and how they might move differently.

But I wanted to ask Stelarc and the panelists about what animates us? What of the emotive as well as the locomotive? These are questions of affect and energy which this type of work cannot really address and maybe we shouldn’t insist that it does because in so many other ways it is pushing us into new territory. Instead Jane Goodall raised the notion of motivation in relation to movement and suggested that Stelarc disconnects the links between them, so that motion becomes mechanical rather than psychological and does not reflect the motivation of the mover. A manifestation, she said, of the unravelling of evolutionary thinking.

So is Stelarc a post-evolutionary thinker? Well perhaps he is a post-evolutionary artist…As he is fond of saying, Stelarc is interested in finding ways for the human system to interact more effectively with the increasingly denaturalised environment this system finds itself in, and extending the body’s capacities for useful (and useless) action. And don’t forget this latter point. It’s easy to get caught up in Stelarc’s spiel, brilliant and provocative as it is; it is nonetheless an artist’s statement and the suggestive utility of much of his thinking should not stop us enjoying the spectacle of a genuinely creative mind at work and a laugh which is so richly suggestive of Stelarc’s profoundly ambiguous view of the world.

The laugh returns us to the basic contradiction of all Stelarc’s actions in their return to the image of the artist’s body in a way which reinforces the effect of its presence and its adaptive capacities. If the body really were obsolete, Stelarc would be of no greater ongoing cultural relevance than Mr. Potato Head. Adaptivity is the real message but Stelarc knows that obsolescence is a better long term sales strategy.

Stelarc: extra ear | exoskeleton | avatars, presented by dLux media arts and Casula Powerhouse Arts Centre, Museum of Sydney, February 20

RealTime issue #30 April-May 1999 pg. 18

© Ed Scheer; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

A major aspect of technoculture comes from “mystical impulses behind our obsession with information technology.” That, in essence, is the central thesis of an ambitious tome entitled TechGnosis by San Francisco writer Erik Davis. Davis has written numerous snappy articles in this field for Wired, The Village Voice, Rolling Stone, 21 C, Lingua Franca and The Nation. However in TechGnosis he attempts to touch upon the entire history that connects the spiritual imagination to technological development, from the printing press to the internet, from the telegraph to the world wide web.

A major aspect of technoculture comes from “mystical impulses behind our obsession with information technology.” That, in essence, is the central thesis of an ambitious tome entitled TechGnosis by San Francisco writer Erik Davis. Davis has written numerous snappy articles in this field for Wired, The Village Voice, Rolling Stone, 21 C, Lingua Franca and The Nation. However in TechGnosis he attempts to touch upon the entire history that connects the spiritual imagination to technological development, from the printing press to the internet, from the telegraph to the world wide web.

In the process Davis discusses in detail myriad cultural and religious figures and movements, from Plato to Marshall McLuhan, from Jesus Christ and Buddhism to Timothy Leary and Scientology, from Pierre Teilhard de Chardin to William Gibson. What is surprising is that, despite the density of ideas in this tome, it is always readable, inspiring The Hacker Crackdown author Bruce Sterling to comment that “There’s never been a more lucid analysis of the goofy, muddled, superstition-riddled human mind, struggling to come to terms with high technology.”

According to Davis, “TechGnosis is a secret history because we are not used to dealing with technology in mythological and religious terms. The stories we use to organize the history of technology are generally rationalistic and utilitarian, and even when they are cultural, they are rarely framed in terms of the religious imagination.”

On a general level, says Davis, this has to do with modernity’s “ultimately misguided habit of treating religious or spiritual forces solely in terms of the conservative tendencies of various institutions, rather than as an ongoing, irreducible, and indeed, irrepressible dimension of human cultural experience, one that has liberatory or avant-garde tendencies as well as reactionary ones.”

Davis’ ability to shift from popular culture to historical fact peppered with pop terminology fits an intriguing trend in cultural studies. TechGnosis sits comfortably alongside such books as Greil Marcus’ Lipstick Traces, Mark Dery’s Escape Velocity, Mike Davis’ City of Quartz, Andrew Ross’ Strange Weather and Darren Tofts’ Memory Trade. In this regard TechGnosis narrowly escapes the categorisation of being a book about ‘spirituality.’

“Although I deal more sympathetically with religious material and ideas than most of those authors, I feel far more affinity with their approach than with more self-consciously ‘spiritual’ books, which tend to deny the role of historical, economic, and political forces”, says Davis. “I just happen to be drawn to that peculiar interzone between popular culture and the religious imagination.”

That interzone inevitably draws Davis towards some dangerous realms where ‘popular culture’ and ‘imagination’ are all too prevalent. While Davis carefully explores the genesis of such movements as Scientology or the Extropian movement and points out the totally bizarre substance (or lack) of both, he manages to avoid the pitfall of making harsh value judgments. “When I embarked on this project, I decided that developing a cogent critique of spirituality would add yet another layer of complication to an already dense investigation”, he says. “Confronted with a curious belief system, I am more interested in how it works than I am in criticizing it; I wanted to allow the power of the various world views to arise as fictions.

“It’s like camera filters: what does the world look like if you momentarily wear the lenses of a conspiracy theorist, a UFO fanatic, a conservative Catholic? By allowing eccentrics and extremists their own voice, I hoped to lend TechGnosis a kind of imaginative force that more explicitly critical works lack.”

In the burgeoning world of ‘secret histories’, the shadowy figure of ‘sci-fi’ author Philip K. Dick looms as a major influence. Dick’s work, riddled as it is with visionary belief systems tinged with perpetual paranoia, never sat comfortably in the cliche-ridden world of pure science fiction. “I emphasize the visionary acuity of his works, which have influenced me as much as McLuhan or Michel Serres or James Hillman”, says Davis. “I am especially drawn to his ability to treat religious ideas and experiences in the context of late capitalism and our insanely commodified social environments.”

Similarly, McLuhan is a “complex figure, full of bluster and brilliance”, says Davis. “He deserves a complex engagement, and I certainly distinguish myself from Wired’s simplistic recuperation of McLuhan, which turns on the same sort of selective sampling of his work, only in reverse. For one thing, McLuhan nursed vastly darker views about electronic civilization than most people believe—his global village is an anxious place. But unlike most of today’s media thinkers, he considered himself an exegete rather than a critic or theorist. That is, he wanted to uncover the spirit of electronic media rather than provide the kind of structural political critique that people are more comfortable with these days. To do that, he used the imagination of a profoundly literate (and religious) man, allowing analogies as much as analysis to lead him forward. He read technology, whereas most critics describe or deconstruct it. And though he said a lot of stupid stuff, and participated too willingly in his own celebrity, he laid the groundwork for our engagement with the psycho-social dimension of new media.”

The power of the word runs throughout TechGnosis—from Guttenberg’s printed Bible to the study of the Kaballah, from Gibson’s Neuromancer to the use of hypertext on the net.

“A troubling aspect of the new technologies of the word is the invasion of technological standardisation into the production of writing”, says Davis. “Behind this problem lies an even larger one: the invisibility of the technical structures that increasingly shape art and communication. As we use more computerized tools, we necessarily engage the structures and designs that programmers have invested in those tools. Then there is the issue of the internet; an immense writing machine that, for all its creative power, encourages sound-bite prose, superficial linkages, and the confusion of data and knowledge. The Gutenberg galaxy is finally imploding, and we have yet to come to terms with the psychic and cultural consequences of our new network thinking.

“Of course, invisible structures have always been shaping thought and expression, in one form or another. The trick now is to explore ways to let the creative, recombinant and poetic dimension of language express itself in an electronic environment where the monocultural logic of a Microsoft can hold such enormous sway. I still think that hypertext and collaborative writing technologies have enormous potential, but in the short term I see a rather disturbing dominance of standardisation, as American English continues to transform itself into an imperial language of pure instrumentality.

“It’s my hope that the net will enable us to move through the gaudy circus of superficial relativism into a more serious engagement with the ways that different institutions, practices, and cultural histories shape a truth that nonetheless hovers beyond all our easy frameworks”, says Davis. “The way ahead, to my mind, involves the synthesis or integration of many different, sometimes contradictory ways of looking at and experiencing the world. The endless fragmentation of (post)modernism is boring: we ourselves are compositions of the cosmos, a cosmos we share in a manner more interdependent than we can imagine, and that cosmos calls us to construct new universals. Perhaps they will be universals of practice rather than theory; if you do certain things, certain things will happen. A new pragmatism. If we need religious forces to bloom in order to feel our way through this highly networked world, so be it.”

Erik Davis, Techngosis, Harmony Books (Grove Press), 1999

RealTime issue #30 April-May 1999 pg. 23

© Ashley Crawford; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

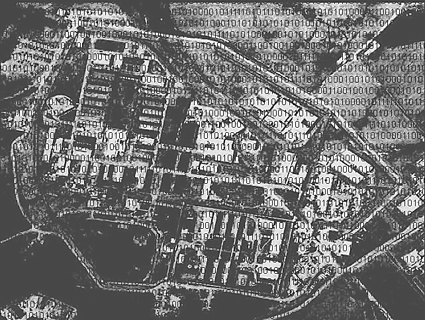

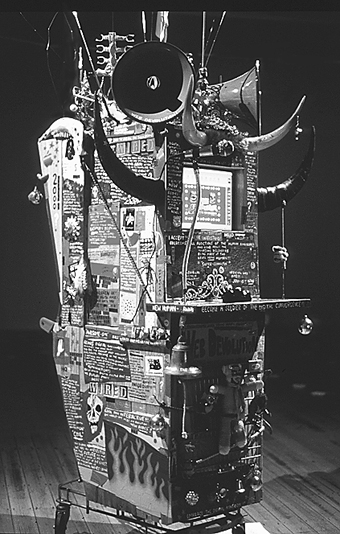

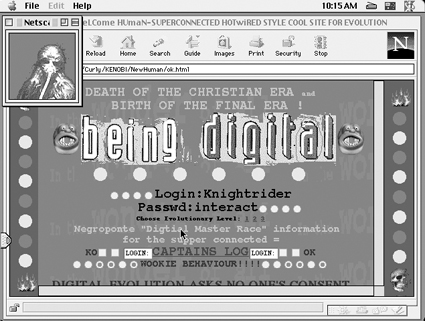

Retarded Eye Team (Vikki Wilson and Cam Merton), Radium City: Harvesting the Afterlife

“The only living life is in the past and the future…the present is an interlude…[a] strange interlude in which we call on past and future to bear witness we are living.”

Eugene O’Neill, Strange Interlude, 1928

In the 1970s, “Suture” was a popular term for procedures by means of which cinematic texts would confer subjectivity upon their viewers. Not only a medical process, it was also a way for thinking through constant audience reactivation through sequences of interlocking shots. Although no one doubts the capacity of new media art to activate an audience, that activation has all too frequently been one-dimensional: either cool data processing or hot-palmed mouse clicking. The Future Suture exhibition at PICA (Perth Institute for Contemporary Arts) for the Festival of Perth was surprisingly different. This engaging, difficult and exciting web art installation by 4 Perth artist collectives took an unexpected turn into humour. Clearly that is their bandage for the haemorrhaging hubris of our strange interlude.

Future Suture is no eye candy, but hard chew multi-grain mind cookies. Audiences had to work hard and fast to make sense of and gain enjoyment from the work that was interlocking the old into the new. With imaginative stitching all 4 installations explored ways of sewing previous subjectivities to the gash opened by the technological transformations of future horizons.

Horizons (http://www.imago. com.au/horizons – expired) was minimalist in terms of room decoration, but big on intertextuality and cultural resonances. Malcolm Riddoch, one of the artists, explained that “the site’s basically a self-reflexive boys’n’their toys kind of thing, linking militarism with a specular approach to knowing and perception through a games interface, but fully web functional.” The project works on a number of levels and has some fascinating things to say about time, indiscriminate targets and horizon theory. On one level this is a simulated geo-scopic rocket launching game resplendent with nasty voiced instructions for nose-coned views of hyper-intertextual destructive scopophilia—part Operation Desert Storm with hay-wire meteorology, and part firecracker home video—with a fair whack of Heideggerian theory as payload. Yet this rocket game also resonates with the naturalised absurdity of scud missile video playback and so-called radar targets that are in fact schools. Participants select a site on mainland Australia and launch a rocket at it gaining a view of the world from the rocket’s nose cone at 500m. The indeterminacy of the target acquisition is sublime. The program blurb proclaims, “Horizons is a non-profit public service funded by the Federal Government of Australia and freely available to all Internet citizens world-wide.” This is satanically perceptive. The Federal Government does in a sense facilitate the technology for launching attacks on Australia from anywhere in the world. But of course we can now stand proud that the attacks are self-inflicted and that our technology still calls Australia home.

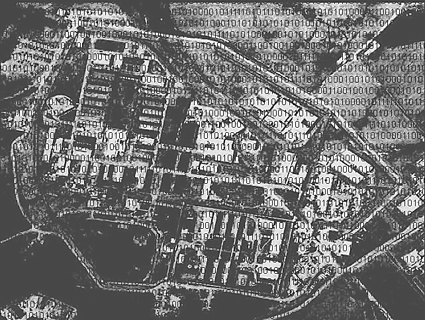

In contrast, Radium City (www.imago.com.au/radium_city – expired) by the Retarded Eye collective achieved a funky juxtaposition between installation and screen. The setting was welcoming techno-boudoir baroque. In one corner sat a little Mac storyteller, the rest was dominated by an enormous Italianate bed with mirror and 2 TV monitors showing male and female soap stars getting deep, while below them the electronic bedspread pool was swelling with aerial urban images stitched through with endless binaries. The project sought to position the viewer as a sleepwalking flaneur via science fiction scenarios of the virtual future city that continually re-wrote themselves via a digital process of automatic writing. Here new technologies were mixing it with old techniques on a constantly refurbished palimpsest. The ideas were a heady mix. The pull of binaries was a buzz. The bed and the multi-plot storybook became 2 magnets. The interlude between was strange, but the text kept rewriting itself, mutating over time.

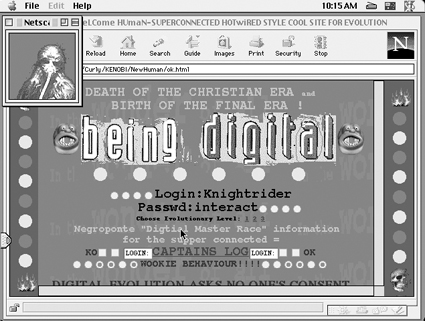

Of all the installations, Project Otto (http://www.imago.com.au/otto – expired]) was the most dependent on physical presence and manipulation of the environment. This huge and hungry hardware project was a dynamic bandaging of an unusual combination of old and new technologies. The networking interactions spiralled through radio, image, sounds, web and the tactile stimuli of a metal trolley on a rough-hewn floor. The stunning images of bodily close-ups sprawled across the wall like a Persian rug were activated by a mobile antenna trolley that picked up different radio frequency emissions from seven overhead disks that in turn generated sequences of deeply textured soundscapes. The images could be further engaged via a Dr Who-like console box. This was a good sweaty interactive space. It was damn sexy the way the installation totally activated a tactile, aural and intimate subjectivity that stimulated the imagination. The mix of radio and web, the old and the new, people in the gallery space and the site on the web, was tangible. As is the enormous potential of this project.

Tetragenia is aptly described as a “trojan web site that accumulates consumer profiles under the guise of ‘caring’. Participants are harassed in a prolonged, strategic email campaign.” Our hell is excess data, corporate-speak, dietary ethics, common sense advice for life, electronic surveillance and technological abuse. Tetragenia turns this into an art—ridiculing the new human face of corporations, the wealth of waste and electronic intrusions. At the same time, it offers eminently reasonable nutritional and ethical suggestions that loop in on themselves showing something a little less benign. It’s a call to the consumers of the world to unite to promote ethical trade practice; and it cuts a fine line between a new seriousness and a classic piss-take. This absurdist installation tests the limits of the traditional ethics of privacy and marketing with harassing emails and data-frenzy. It is exciting to finally come across web art that not only engages with the contemporary info-excess but also does so with great comic timing. However, the timing of constant server breakdowns was deeply aggravating but, as Marshall McLuhan once said, “If it works, it’s obsolete.”

When it comes to imaging future horizons, as Malcolm Riddoch ruminated, the “horizon is the rocket eye view of the world. The spatial limits of the horizon is carried with us so that the horizon can never be reached.” This can be seen as a cautionary metaphor for rocketing into future shock. But if we consider that by looking back, the past becomes another horizon—does this mean that we can never remember the point at which we were, or at which the horizons looked broad and welcoming? Or that history’s horizons are carried with us but cannot be seen from the present and can never be reached in the future? This made me wonder, what’s the big deal of getting to the horizon? Then again no one is happy to stick around in the strange interlude of the present. The problem is that if the future is not sutured to past horizons, sun-blindness is inevitable. Future Suture’s solution is to bandage these wounds with some serious humour.

Future Suture, curator Derek Kreckler, joint initiative between FTI (The Film and Television Institute) & IMAGO Multimedia Centre Arts Program, Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts, February 11 – March 7; links to 4 projects at http//www.imago.com.au/future_suture [expired]

RealTime issue #30 April-May 1999 pg. 24

© Grisha Dolgopolov; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Subject: etc

As I have noted elsewhere: “Screen Culture—the nomenclature is out there. A conjugation designed to expand the parameters of moving image organisations and their exhibition practices to incorporate multimedia and the digital arts and to encompass the output of all practitioners ‘working within the screen frame.’” I confess to an unhealthy predilection for creating and dissecting definitions. Seeking out ‘screen’ in a (generally less preferred) lexicon, I read: “a smooth surface, such as a canvas or a curtain, on which moving images etc may be shown.” I become obsessed with the idea that the subject of my current project is this ‘etcetera’. It troubles me, I lose sleep over it. I consider that Funk and Wagnalls may have put the etc in the wrong place. It is my goal to reposition it. So, I’ve packed up my theoretical premise and hit the road. I have named my axiom expandingscreen and I’ve just spent 30 hours on the way to Helsinki cleaving the title.

Subject: Muu, Helsinki; Date: Oct 17, 1998

Happy to discover that my visit coincides with Helsinki’s annual herring festival, I cross the marketplace each morning on my trek from Katajanokka island to Kiasma for the MuuMedia Festival.

Muu (‘other’ or ‘something else’) is staged by AV-arkki, an organisation which provides facilities for Finnish media artists and represents their work. The event began a decade ago with the Kuopio Video Festival in eastern Finland and has developed into one of the largest events of its kind in the Nordic countries. Like many organisations and festivals originally intended to represent video art, MuuMedia and AV-arkki are in the process of expanding their program in order to accommodate web art, CD-ROMs and interactive media installations. The necessity of creating appropriate exhibition environments is accentuated by the location of the festival within several spatial realms: museum space (Kiasma: Museum of Contemporary Art), gallery space (Otso), collective art space (Cable Factory) and continuously contested urban space (Mobile Zones). The special focus of MuuMedia 1998 is ‘global and indigenous’ a framework addressing issues of globalisation, indigenous culture, power and networked information.

The prominent and dynamic architectural design of the newly opened Kiasma provides the festival with its centre. A contemporary art museum, purpose-built in an age where exhibition practice is undergoing considerable transformation, Kiasma attempts to reorder art and information hierarchies by creating a responsive, anticipatory space for the reception of art in all its forms. The emphasis on communication flow and active or dynamic reception is conceptually expressed in the name itself which has its roots in chiasm: the intersection of 2 chromosomes resulting in the blending and possible crossing over at points of contact and also the X-like commissure which unites the optic nerve at the base of the brain. Despite its desire to embody these forward thinking principles, Kiasma in operation is not proving adequately equipped as the site for the screening component and the digital gallery. Dreadful acoustics (which equally impact on the media art in the permanent collection), bad projection design and handling, and an under-informed staff are resulting in loss of audience—the hundreds of visitors drawn to the building each day are not made properly aware of the festival and the committed audience are battling through a haze of interruptions and cancellations.

The Mobile Zones project is proving to be the most successful component of the festival. Curated by Heidi Tikka, the various works explore the possibilities of art as activism, examining the urban landscape and its transformations. Helsinki is busy with preparations for 2000 when it will simultaneously celebrate its 450th anniversary and its reign as European capital. Nick Crowe’s deliberately lo-fi community web project A Ten Point Plan for a Better Helsinki (find link at Kiasma site) required the participation of citizens who contributed proposals for the redesign of a controversial public space near Kiasma, while Adam Page and Eva Hertzsch investigated anxiety zones in urban space with their demonstrations of Securoprods, a transfunctional security gate/revolving door.

Subject: ZKM, Karlsruhe; Date: Nov 8, 1998

Three hours in the gardens surrounding Karlsruhe’s Schlossplatz (the only site to recommend the town aside from ZKM and a temporary beer exhibition) and I am still scrawling notes on Pavel Smetana’s The Room of Desires. Images in a darkened room are generated in response to information received from sensors bound to my wrists and forehead. Something allows me to recognise the constructedness of it, but this just serves to increase my anxiety at seeing my ‘psyche’ projected. Though private, the zone has the potential to become public, and the sense of surveillance is heightened by those white-coat clad attendants who swabbed me and taped me up.

The Room of Desires is one among many interactive installations that comprise the temporary exhibition Surrogate, the first showing in situ of work by artists in residence at ZKM’s Institute for Visual Media. The ZKM (Zentrum für Kunst und Medientechnologie | Centre for Art and Media, www.zkm.de) is the realisation of an 8-year development project whose premises in a transformed munitions factory were opened in 1997. Consisting of 2 exhibition departments (the Museum of Contemporary Art, the Media Museum), 2 production and development annexes (the Institute for Visual Media, the Institute for Music and Acoustics) and an integrated research and information facility (the Mediathek), ZKM adopts an interdisciplinary approach to the presentation, development and research of visual arts, music and electronic media. Ex-Melburnian, artist and director of the Institute for Visual Media, Jeffrey Shaw, tells me that the departmental proximity “creates an environment where the museums reflect an ongoing, inhouse creative identity”, a dynamism enhanced by the potential for “the production zone to be transformed into a public space.”

I find pleasure in the Mediathek, a veritable treasure chest for an archive rat. A centralised database establishes instant access to 1,100 video art titles, 12,000 music titles (with an emphasis on the electroacoustic) and a comprehensive collection of 20th century art and theory literature. Download from what is probably the world’s largest CD-ROM jukebox system (soon to be converted to DVD) and receive at any of the 12 viewing stations (designed by French-Canadian media artist Luc Courchesne) or the 5 historically significant listening booths designed for Documenta 8 in 1987 by Professor Dieter Mankin. After indulging myself on a self-programmed Bill Viola, Tony Oursler, Gary Hill retrospective, I took some literary time out to read Donald Crimp’s On the Museum’s Ruin. In a study of Marcel Broodthaer’s Musee d’Art Modern series of installations/exhibitions which radically investigate the position of the museum, Daniel Buren is cited as claiming, “Analysis of the art system must inevitably be undertaken in terms of the studio as the unique space of production, and the museum as the unique space of reception.” ZKM is an institution formally enacting this kind of analysis.

Subject: AEC, Linz; Date: Nov 17, 1998

Watching snow fall on the not-so-blue Danube from the offices of ARS Electronica Center in Linz (www.aec.at). Spent the train trip from Karlsruhe to Salzburg reading Derek Jarman’s (sort-of) autobiography, Kicking the Pricks (Vintage 1996). Speeding through the Black Forest on his accounts of making-out at the old Biograph watching German soft core featuring semi-clad damens running through said geographical terrain. In 1987 Jarman says: “the Cinema is finished, it’s a dodo, kissed to death by economics—the last rare examples get too much attention. The cinema is to the 20th century what the Diorama was to the 19th. Endangered species are always elevated, put in glass cases. The cinema has graduated to the museum, the archive, the collegiate theatre…”

Jarman argues the case for the cheapness and immediacy of video. What strikes me, is the degree to which the moving image has impacted on the tenets of museology in the decade since Jarman establishes the museum as a static place. Paradoxically, the contemporary art museum is precisely the location of video art and media installations, and (in most cases) instead of the museum subduing media art, the development of new technological forms has necessitated a vast rethinking of the museum as a space of reception.

ARS Electronica Center is conceived and operates as the antithesis of Jarman’s museum. It services local and global industries, artists and educational institutions in addition to presenting and maintaining a museum space designed to anticipate the future of what commentators (and I guess that includes me) like to call “the information age.” Its integrated approach, which actualises the whole concept of convergence, produces an environment where the application of everything from virtual reality through computer animation to video-conferencing is applied in all disciplines in a manner that promotes practical and theoretical discourse between commerce, media art and education. Co-director of this ‘Museum of the Future’, Gerfried Stocker, tells me that the emphasis here is on process and “how to give things a value without a history.”

This radically challenges traditional systems of value and analysis in a manner that is arguably appropriate to the rapidity with which new technologies emerge. I find it difficult to assess a lot of high-end media art, and this has never been more the case than both here and at ZKM where the technology is so impressive in itself that the core elements of a work may indeed be the science of its construction rather than its artistic endeavour. I still favour works which don’t foreground the technological achievements over content. At ARS Electronica, a work like World Skin (winner of the 1998 Golden Nica for Interactive Art in the Prix ARS Electronica) by Maurice Benayoun and Jean-Baptiste Barriere will endure the potential redundancy of the environment within which it is conceived and produced. Enter the CAVE (AEC’s permanent 3-walled virtual reality environment) armed with a stills camera and move through a virtual landscape—a photo-real collage of images from different wars. Start to ‘shoot’, take images with the camera like a ‘tourist of death’ and you (visually) tear the skin off this world. It transforms into a white void, only shadow traces like cardboard cutouts remain. The experience is strangely connected to and distant from the bloody (non-virtual) reality of war.

Subject: etc; Date: Dec 6, 1998

I am allowing myself to be in process. There are not yet conclusions to be drawn. Perhaps the etc would be better positioned after “or a curtain.” Halfway through my research tour and I am suffering from the desire to see the debate which should be surrounding the planning of 2 moving image centres in Australia (Cinemedia at Federation Square, Melbourne, and the Australian Cinematheque at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney) become more urgent and more public. In the meantime, I am expanding my waistline on gluhwien, cheese and root vegetables.

Clare Stewart is Exhibition Co-ordinator, Australian Film Institute. Expandingscreen has been enabled by funds from the Queens Trust For Young Australians, the Australian Film Commission, Cinemedia and the Australian Film Institute.

Of related interest, see “Finnish shortcuts”, Melinda Burgess, RealTime 28, December 1998 – January 1999.

RealTime issue #30 April-May 1999 pg. 21

© Clare Stewart; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

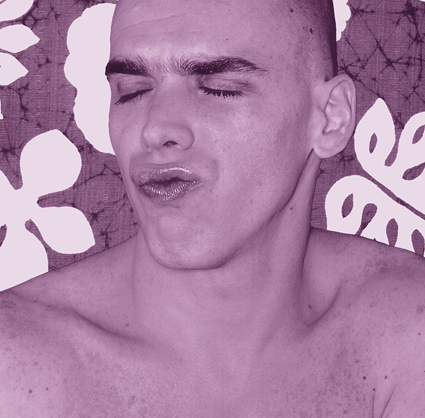

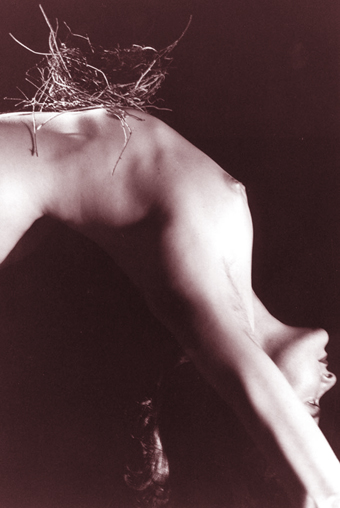

Javier de Frutos

photo Chris Nash

Javier de Frutos

When I spoke to Javier De Frutos he had just finished his season of The Hypochondriac Bird which was part of the Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras Festival. Our discussion covered the production itself, his career as a London-based artist with Venezuelan origins and seemed to constantly veer back to what he sees as a crisis in dance at the end of the millennium.

Geography—Community

A lot of people who see my work find it difficult to place as a product that has come out of England. Although I am an unequivocal member of the British community I am an outsider—all communities have outsiders and all immigrants, no matter how hard they try, are always outsiders. Countries need that. I don’t know if it’s an outside perspective—I never pass judgement on the things that I am experiencing. I’m very direct so I’m always at odds with ‘Englishness’, yet I think that is the very reason why I have remained in England, even while not liking it—the confrontational nature of my work and people who cannot deal with it.

I think I understand the pace of a country like Australia that has more beneficial weather. I’ve never produced my work in Venezuela, my native country—always in cold countries and I think that conflict shaped the work. The tension works because the work is so autobiographical. I’m not very happy about sharing happy things but dealing with more anguished moments. Then somehow the work becomes an outlet. Happy moments are so few I don’t know if I would share those.

In the context of Mardi Gras I’m becoming more aware of how diverse as a community we are. I had a great big sense of pride when I came—I caught the launch at the Opera House and I was surprised at how political it was and how attentive and interested those 20,000 people were. I am also surprised at how—mainstream is not the right word—it is a major festival in this city.

The Hypochondriac Bird

I’m actually sorry that it was the first example of my work here because it comes without any preparation. It’s probably the least direct work that I have produced. But there’s a line in the work that deals with the absolute boredom of a long term relationship. As Wendy Houstoun commented, it really looks like the 2 of us had different books of instructions for this relationship and suddenly, having read the books, we realise we’re not even in the same library, the same bookshop.

I think there is a threshold of pain in (the sex scene) that one has to go through because we [De Frutos and Jamie Watton], as performers, go through that in the work. The more we did the sex scene the more bored we were with it and we started to match the way the audience felt. The audience is a very contagious source of energy. Together, we had to reach that level where nothing is happening any more, which happens to relationships when they are on their way out. Someone commented on the structure of the piece where the climax of the work is not a climax, or such a long climax that it stops being a climax and becomes an anti-climax. It introduces a new sense of structure. So the work starts as representational, becomes high melodrama, then the ‘installation’, then the drama again. That meant you had to pace yourself which caused problems with the audience.

It’s also quite brutal and realistic—when you look at the vocabulary we had to go for a more realistic range and it’s tough because it doesn’t necessarily satisfy dance-goers. And it goes back to the whole question of what is dance anyway? This is probably one of the most danced works I have ever done. From beginning to end it’s non-stop dancing. It might not be recognisable as that qualified thing that we know as ‘dance’, which is frightening in itself—that we cannot move on.

I think there was a mistake in the Mardi Gras’ publicity. I never did a version of Swan Lake—it was a piece that used Swan Lake’s score because those ballet references are close to me—the sound. Music is very much like perfume. My mother used to wear Yves Saint Laurent Rive Gauche in the beginning of the 70s, and when I smell it my mind just goes back—I see the bottle, I see the bedroom…the music does that to me. What does it do for the audience? If you have a sound that is immediately recognisable like Swan Lake you go for the narrative you know and the layers start—you try to match what you see with what you think you know—and it becomes an interesting exercise for those who allow it to happen. The Mardi Gras adds another layer——the choreographer is gay and what you’re seeing is a gay love story. So you go to the theatre with all that information—perhaps too much.

Design

The Hypochondriac Bird was the first time I was working in a very clean, clear looking space—I always work in very black spaces. My partner, an Australian Terry Warner, is the set and costume designer and Michael Mannion is the lighting designer. They are the oldest members of the company and it was something we wanted to work on. When you work in a black space you have the possibility of making the space smaller or bigger with lights—the magic of the black box. When you work on a white space you never forget how large the space is and psychologically it gives it a grander context, emphasising how irrelevant to the order of the world the lives of these 2 people are.

The point with the design (a aquare of illuminated clear plastic pillows) was to make things that could be everything and nothing and it was up to the audience to decide what they were seeing. I realised that the works I had done in the past had a sort of half-finished architecture. (I studied architecture for about a year and abandoned it.) There are always marks on the floor that could be a laid out plan. The original design was a half-finished house—every clear plastic pillow becomes a brick.

Movement and Meaning

I’m a great believer in first of all creating an atmosphere—the movement can be quite unimportant but if the atmosphere is right then the movement can be right. In a workshop years ago this playwright got this actress to do the same scene, peeling potatoes, in many different places in the house. It became so clear. Dancers say ‘my character wouldn’t move that way’ or ‘that movement doesn’t mean anything, doesn’t signify’—like 32 fouettes signifies a lot anyway—like, ‘thank god for the 32 fouettes, now I get it, now I know what she’s feeling!’ So suddenly it was clear to me that the movement wasn’t important but the context of the movement and the intention of how you did the movement. So describing it means nothing—she’s peeling potatoes—and suddenly the physical action changes in her muscles and peeling potatoes becomes the medium to express something else—she could be stabbing someone in the stomach. I can’t bear the idea of trying to find a movement that’s going to mean something. What’s the point of looking for something that’s going to look like a kiss when the kiss is such an effective thing to do?

Dance

This piece has been a major turning point for me in regard to the effectiveness of dance. At one point we have to stop looking at the museum pieces and the function of the body. I’m so terrified now that most dancers I know are concerned about whether their lower back is aligned with their neck and there’s nothing else. Something that was only meant to be a tool for you to feel better physically suddenly became an aesthetic goal. It seems to be the only branch of the arts that doesn’t want to suffer. If you’re really worried about a healthy body and healthy mind you’re not an artist any more—just let it go. Go and teach aerobics or something, but you can’t just go on stage and tell me how aligned you are because I’m not going to connect with you at all—certainly not with my own alignment.

What happened with the underground scene—it’s just completely gone. Some of the so-called underground productions that are happening in London are frighteningly similar to commercial productions but with less money so they don’t look as good. Does anyone have anything to say for themselves any more? Who wants to be second best? Is it some kind of millennium bug that suddenly we have to go into more direct ways of communicating, that dance is starting to lose its touch? People don’t read poetry any more, they read newspapers.

The Hypochondriac Bird, choreographer, dancer and music Javier De Frutos, dancer Jamie Watton, music Eric Hine, lighting design Michael Mannion, set and costume design Terry Warner; The Seymour Theatre Centre, Sydney, February 10 – 14

RealTime issue #30 April-May 1999 pg. 29

© Erin Brannigan; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

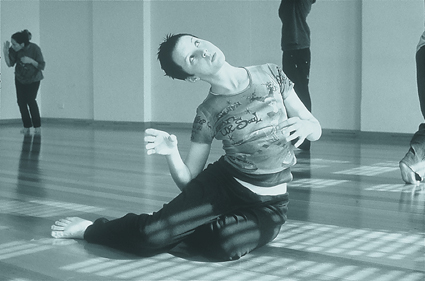

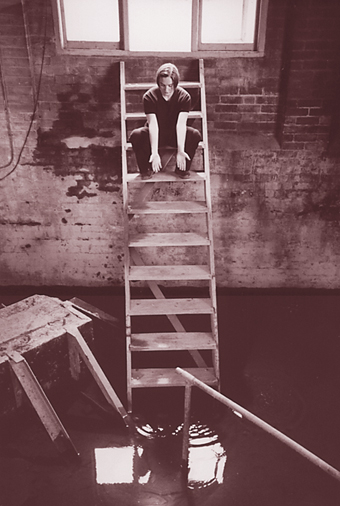

Peter Trotman and Andrew Morrish, Avalanche

photo Neil Thomas

Peter Trotman and Andrew Morrish, Avalanche

Trotman and Morrish are like those old couples who have cohabited for decades—they know how to share a bed (read stage). Although they are very different performers, they slip in and out of each other’s narratives with ease, turning the tables and reversing predicaments. Each successive performance extends the work of the previous night (the season runs to 6 performances). The spoken commentary by Morrish proceeds like the automatic writing of the Surrealists, uncensored, and full of free associations. Morrish happily assumes maniacal, arch and eccentric characters and does so in this somewhat apocalyptic piece. By contrast, Trotman’s guileless persona creates trouble and amusement only indirectly. His speedy movement is light and elfin, his little looks to camera are wide-eyed and open.

Avalanche has much more ‘dancing’ than their last piece, The Charlatan’s Web, perhaps because there is greater usage of music. Trotman and Morrish are not trained dancers but they move with commitment and personal style. In fact, their lack of training produces a certain sort of critique of masculine ways of moving—they are not sporty men, they are not men ‘doing’ dance, they are happy to be laughed at, and they cover space in unusual ways, neither seeking nor rejecting grace. The effect is of seeing men work together and co-operate with a mind to the work at hand. Avalanche will be shown as part of Sydney’s antistatic dance event this year.

Avalanche, Peter Trotman and Andrew Morrish, Dancehouse, Melbourne, March 5 – 14; antistatic, The Performance Space, Thursday March 25, 8pm.

RealTime issue #30 April-May 1999 pg. 33

© Philipa Rothfield; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

How did you define yourself when you were starting out in dance? What points of reference did you use? Who was there to help you with your next move? There can be significant turning points for young dancers which either assist to transform them into professional dance practitioners or help them to realise a life of dance may not be quite what they had expected. Ausdance responded to these issues in youth dance in 1997 with the inaugural Australian Youth Dance Festival.

Creating the right environment for the facilitation of creative development is an important emphasis of the Australian Youth Dance Festival which this year is being held in Townsville, Queensland from June 27 to July 2. The initiative brings together youth interested in or already practising dance to gain further knowledge and to formulate networks of peers across Australia. The program is based on workshops, forums, discussions and performance.

Catering for all levels of dance, the festival has 3 major strands; one for young dancers who are still students, one for new dance graduates and independent artists, and one for youth dance leaders and teachers. Youth, for the purpose of the festival, is defined as being anyone from 10 to 30 years of age.

Festival tutors have been selected firstly for their specialised knowledge in a certain field and secondly for their ability to work with people of differing age groups and dance knowledge. Students who have had little dance experience will be able to participate and enjoy the festival equally with those who have studied dance technique intensively. Technique sessions will be available every day in many different dance styles.

Some of the festival’s scheduled workshops cover dance education for teachers; skills development for young dance writers and youth dance leaders; and choreographic, film and new technology workshops for independent choreographers and dancers. Panel discussions and forums will be presented by emerging artists on such topics as the processes behind choreography; how cross cultural works fit into the landscape of Australian dance; gender in dance; the moving body in relation to film; the importance of dance research; the relationship between traditional and contemporary dance practices; and dance and meaning. As well as emerging artists, more established artists such as Chrissie Parrott will deal with topics like Motion Capture and the use of technology in dance.

To play host to a major national youth dance event is an exciting prospect for the Townsville dance community. For this reason the Festival’s performance component has been integrated into the local community as much as possible.

Local residents and the many tourists in the region will be able to enjoy free lunchtime outdoor performances presented by young people, in the centre of the town throughout the week. The Townsville Civic Centre will host 2 large public performances on June 28 and 29 featuring the Festival’s resident professional dance company, Dance North and its youth counterpart, Extensions Youth Dance Company and international and interstate dance groups like Steps Youth Dance Company from Perth. A range of new work by independent choreographers will be presented on a daily basis.

Young dance students (10 to 15) will be involved in a special component of the program, the Community Dance Project which will focus particularly on dance and art making processes. Victorian choreographer Beth Shelton and visual artist from Tracks Dance in the Northern Territory, Tim Newth, will lead this project with the participation of the Mornington Island Dancers. Beth and Tim have previously worked together on large-scale community projects with young people and are able to work with students at many skill levels. Other dancers and visual artists will assist them in making the work, which will be shown on Magnetic Island on the last afternoon of the Festival, Friday July 2.

RealTime issue #30 April-May 1999 pg. 30

© Naomi Black; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

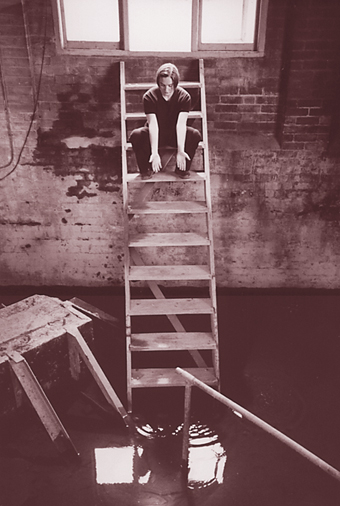

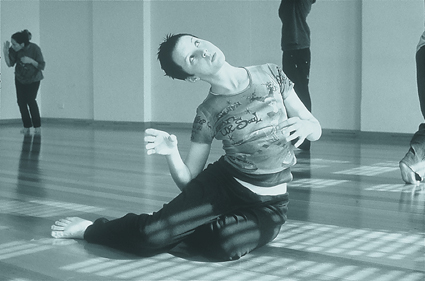

One Extra Dance, workshop

As its contribution to the celebrations for Dance Week 99, One Extra Dance presents Inhabitation II directed by Tess de Quincey with sound design by Panos Couros. This is a work for a company of young performers, in which “the environment of the body negotiates and uncovers the structure and sensibility of the site, investigates a sensory level of existence.” It has grown from de Quincey’s investigations into the process called Body Weather which she is exploring with the group in a series of workshops organised by One Extra in partnership with the Seymour Centre. For DeQuincey, the project builds on the 12 hour performance, Epilogue and Compression with Stuart Lynch at the 1996 Copenhagen International Dance Festival and her choreography for 24 dancers on the chalk cliff coastline south of Copenhagen as part of Transform 97, a festival of site specific dance works. The performance of Inhabitation II is a free event and will be held in the Seymour Centre Courtyard, corner City Road and Cleveland Streets, Chippendale on Saturday and Sunday May 1 – 2 at 6.30 pm each evening.

Dance Week (organised each year by Ausdance) grew from a celebration of International Dance Day observed throughout the world on April 29. Other highlights of this year’s event in NSW include the outdoor dancing extravaganza Streets of Dance in which 100 tertiary dance students join professional artists in an “audacious outdoor program.” Another 200 will take to the football field for the Sydney Swans home game. There’s lunchtime dancing in Martin Place and a Festival of Dance at Darling Harbour. All the major companies will be contributing works and the ever expanding Bodies program kicks off on April 28 with work from contemporary and classical contemporary choreographers as well as a week dedicated to Youthdance. The Australian Institute of Eastern Music’s 3 day Festival of Asian Music and Dance at the Tom Mann Theatre (April 22 – 24) includes eminent South Indian dance specialist Dhamayanthy Balaraju performing for the first time in Australia.

Dance Week 99, Sydney, April 24 – May 2. For further information on Dance Week activities in your state contact Ausdance.

RealTime issue #30 April-May 1999 pg. 31

© RealTime ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Action Situation, Deanne Butterworth, Kylie Walters, Jo Lloyd

photo Kate Gollings

Action Situation, Deanne Butterworth, Kylie Walters, Jo Lloyd

Ideas are multiplicities: every idea is a multiplicity or a variety…multiplicity must not designate a combination of the many and the one, but rather an organisation belonging to the many as such, which has no need whatsoever of unity in order to form a system.

Gilles Deleuze, Repetition and Difference, Athlone Press, London

I cannot tell you what this piece is about. I can only write and in so doing produce another text: a re-iteration destined to become something other than the work itself. Action Situation foregrounds the fact that repetition becomes, inevitably, a moment of difference. Not only was there little replication between the 3 performing bodies, but the work itself highlighted the gap that lies between different, yet related, artforms.

Action Situation is an assemblage of music, script, movement, lighting and space. Each of these forms retained an integrity such that they did not blend into homogeneity. Not only was the music, for example, a distinct yet influential strain but the script also held its own character quite apart from the movement. In other words, Lasica does not choreograph to the ‘beat’ of the music, nor is her movement a mime of an underlying narrative. And yet, the differential participation of these elements did not lead to cacophony. There was a certain cohabitation between sound and movement. Similarly, there was a sense that some kind of narrative was manifest in the dance.

Were we archaeologists, we might be able to unearth the original script that instituted the narrative structure of the work. The ordinary viewer, however, is offered little by way of clues or references. No Rosetta stone is offered to translate from the hieroglyphs of moved interactions into some sense of the everyday. For example, there were times when one, sometimes 2, of the performers trod on the prone mass of the third. Was this a gesture of dominance, aggression, dependence or something else entirely? We will never know. Similarly, movements were performed under the watchful eye of one or other of the performers. There was a sense of bearing witness to an activity, that the performers shared a world, but what that world consists of is anybody’s guess. The only signification I can be certain of was when the 3 held hands during the curtain call. That gesture of naked camaraderie contrasted with the complex, interesting, detail of movement and interaction which comprised the substance. As far as movement is concerned, this is a very dense and satisfying work.

Although there were a variety of actions which could be interpreted as derived from some human strain of interaction, the work had an anti-humanist character, almost post-human. Rather than inhuman, it did not subscribe to any lyricism nor make reference to an instantly recognisable world. Although the audience has to work hard to take the work in (like looking at abstract painting), this is also its strength. Were there to be obvious references to ‘relationships’ or ‘communication’, the central premise would be lost, for Situation Live is about the abyss which lies between different modes. The music interacts with the movement; it does not mirror it. By the same token, narrative is not something to be illustrated by dance. Dance is able to form its own narrative, to be both inspired by the script, but not a servant to it.

Mimesis presupposes a sameness across forms. Action Situation is about difference. Even the language we use to speak of it becomes alien to the work itself. It cannot emulsify the disparate elements. Rather, the textuality of the written or spoken word can only add another layer to this already complex work.

Action Situation, directed and choreographed by Shelley Lasica, performers Deanne Butterworth, Jo Lloyd and Kylie Walters, music Francois Tetaz, script Robyn McKenzie, lighting design John Ford, costume design Kara Baker; Immigration Museum, Melbourne, February 12 – 20

RealTime issue #30 April-May 1999 pg. 32

© Philipa Rothfield; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

West Ryde. Sydney. Australia. Noon.

Through rented white lace to a clumsy rusted clothes line. Dark colours in a harsh New Year’s light. Petunias fighting with weeds. A roaring herb garden, salad smells, lemon balm, Vietnamese mint, laksa dreams, pennyroyal. Green tomatoes staked yesterday and zucchinis big enough to kill. Milka’s beans snaking through from next door. Our garage roller door is shut. Hiding unused, secretive, bought-on-a-whim things. A brick barbie covered in Wandering Jew, native trees—bottlebrush and banksia—give no shade. Green lawn as long as a terrier’s fringe. Still. Waiting for cool change.

The Noon Quilt, trace online writing community, (http://trace.ntu.ac.uk/quilt/info.html – link expired) is a java patchwork of time impressions, a delirium of techno-hippiedom, the irresistible idea of words and moments linked around the globe. Singapore. Brisbane. Arizona. Paris. Brazil. Japan. Manchester. I am touched and transfixed at noon on this hot day.

A world view made of little windows: Trevor Lockwood sees a “fat publisher” who confronts writers at the end of his driveway, begging to be seen in print. Simon Mills writes from the basement. No windows. About his cat who fell off the window ledge. Fell a few storeys, “landed unscathed yet embarrassed.” Val Seddon sees the bench on the patio, where her father used to sit, “lit and warmed by memories that are my protection too.” The teenager forgets to do his English homework and creates a funny and dark view. Phil Pemberton feels like a detective, “Marlowe-like observing the crowds but never getting no closer to the girl.”

There are many women contributors; quilting was always women’s work and there is thought in these patches, a binding of stories, of light and dark shades. I am careful unravelling this hand-me-down, slowly savouring the stitches of time and memory

Helen Flint. Bournemouth. UK. Noon.

At exactly noon, Bournemouth this Seagarden Paradise is upright, shadowless; my front Boycemont Ericstatue and goldeneyed fishpond proscenium the porch I sit on, ten doors from the Channel between fuschia chapters I have just written. And parading past me go paleskin families or solitary on-the-prowl bods dragging huge inflatable plastic moulded floats; oh, 4 hours later they will much slower return floating back up my road, their angry red skin deflating and scorching them.

Some writers, like me, take the view literally, wanting to preserve my frame, where I am right now, my nondescript backyard. Others move cleverly to other frames, the television set, the photograph, a computer screen or a fictional window onto other lives. People use constricting wall views to leap off into imaginative air. Sue Thomas constructs her view in a LamdaMOO, floating “adrift in the endlessly shifting landscapes of a thousand virtual imaginations.”

Characters emerge and re-emerge. An old man drags his feet. Drags cartons of beer. Drags a trolley loaded with corrugated iron and timber. Where is he going? JD Keith finds “empty buildings, idle trucks, and peopleless homes indicat[ing] the Exodus.” Where have they gone? There are unresolved narratives…and notes of new beginnings.

Riel Miller. Paris. France. Noon.

At noon I see tomorrow forming, a tear drop shaking its way down, nourishing the earth, feeding the sky, rushing along twisted pipes, quenching desire, a trickle of satisfaction.

The Noon Quilt trace online writing community, http://trace.ntu.ac.uk/quilt/info.html [link expired]

RealTime issue #29 Feb-March 1999 pg. 16

© Kirsten Krauth; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

And then Princess Di is barrelling towards me, head down, Uzi cocked, the veil of her coronation dress streaming back from her face like a dirty grey curtain. There is death in her pixilated eyes. And I know: She’s gonna wax my republican ass. So I panic. I’m not afraid to admit it. I slap the keyboard, switching from a pistol to something with a little more visceral kick: something involving missiles. I punch the space bar. The launcher exhales. But Di is too close, and even as she detonates (tiara spitting jewellery and giblets in equal amounts) my modem disconnects. I’m dead. (Again). I’ve been soundly thrashed by some 10 year old kid from Arizona. (Again). My only satisfaction lies in the thought that at least I took the ‘People’s Princess’ with me.

It’s about 5 a.m. I’ve been online for almost 3 hours, alternately trudging through the occasionally (read: hardly ever) interesting Australian arm of Ultima Underworld online and slaughtering foreigners with portable artillery in Quake 2. To most people, no part of those last 3 hours had anything to do with hypermedia, the arts, or (worse) self-expression. To me, electronic entertainment is as valid as any other art. To a trained psychologist, thundering about a 3D maze dressed up as a deceased member of the royal family has a lot to say about that 10 year old kid from Arizona.

The idea that hypermedia is limited to extensions of the (more) traditional arts is to limit an already excruciatingly misunderstood idea. Hypermedia as an ‘interactive’ medium which offers the reader/user pathways as opposed to linear narrative should be more than a series of static pages connected like a Choose Your Own Adventure novella. Add pictures and we still haven’t gone very far. Even a Quicktime movie and a soundtrack are nothing but bells and whistles on what is essentially still a piece of ‘straight’ fiction with pretensions.

Hypermedia should give the user a new way of interacting, not merely a new way of reading.

Note: This is not a complicated way of redefining the question so that I can shoehorn video games into a discussion of hypermedia. I can do that easily enough under current definitions. Here goes: Online capabilities in video games are fast becoming standard on the PC, even beginning to bleed over into the lower-end game systems. Sega’s upcoming 128 bit console, the Dreamcast, will have in-built online capabilities allowing users to network and play anywhere in the world.

An important thing to remember is that video games were born on, and exist only on, computers. Unlike pure text, they are the rightful heirs of the digital age, not its bastard children. The ‘links’ between text fragments become the doorways between rooms rendered in 3D. The text ceases to describe or refer to the image, and begins interacting with it, fleshing it out, giving it greater depth. Your average game player becomes blind to the fact that s/he is making choices between fragments, and their reinterpretation of the game becomes fluid. S/he ceases to be an external force acting on the text and becomes another facet of it.

Moreover, unlike hypertext, more than one user can be involved in the same piece at one time. The user passes other users. Their experience is altered by the experiences of others, the ‘text’ moves in more than one direction at one time. The screen updates—unlike new ‘scenes’ created by following links—are invisible, and choices are made on the fly.

To an extent, video games become more hyper than hypertext. As well as offering users the chance to interact with a text/art ‘world’, they allow them to redefine themselves and re-experience it. That kid from Arizona may go for a mock-up of Prince Charles next time. He not only chooses how to interact with the text, but who interacts with the text.

Note 2: Most new first-person shooters (Unreal, Syn, Dark Forces 2, Quake 2) allow the user to download or create their own ‘skins’ for online characters. Fan sites offer homebrew characters for other players to use. (I once saw a naked man streak past me, weapon at the ready. I once saw Gandhi.) These alterations come complete with changing in-game perspective, weapons and sound effects. A selling point of these games has become their flexibility and user definability.

However this choice of personal representation can become far more complex than what ‘skin’ to use. Ultima Online, although flawed, expensive and generally tedious, is a prime example. It allows players to create a character and then ‘live’ it for as long as possible, in real time. The world inside their computer progresses, unlike traditional role-playing games, at the same pace as our own. If you don’t go online for a month, you’ll miss a month of activities. Your house could be burned to the ground by brigands. Your pewter Royal Wedding souvenir mug stolen. The attractive element of the exercise is that you don’t have to follow traditional role-playing staples. You don’t have to be a ‘thief’ or a ‘brigand.’ You could play as a farmer. You would have to buy seed, plant crops, work the field, harvest them, and then find a real person to buy your food. All in real time. Hopefully someone else has chosen to run a shop.

Ultima Online has been heralded as the first of a new generation of games, but it isn’t. It’s really only a step up from the MUDs (Multi-User-Domains) of yesteryear, in much the same way that hypertext is a step away from pure text. MUDs were/are text based adventures which allowed players to move freely, with other users, through a world based around blurb-style descriptions of places and events. Like Ultima Online, there are people, ‘Avatars’, whose job it is to make sure that people a) play in character and b) don’t play like jerks unless (of course) their character class was ‘jerk’, in which case they have to make certain that they play like jerks.

To that extent, MUDs can also be seen as among the earliest and best exercises in hypertext. Their stories are alive, active, and involve hundreds of other players concurrently. I had friends who disappeared into the weird innards and politics of MUDs, never to return. Testament to their addictive qualities and, better yet, to how real a few lines of fictional text (when typed by some ‘real’ kid in Arizona) can become.

Video games in hypertext, like genre fiction in mainstream literature, will probably always be a little uncomfortable. More people may use them and they may often do a better job than their bigger brothers, but that same popular appeal means they’re unlikely to be acknowledged. Perhaps hypermedia, populated as it is by the (hopefully) techno-literate, will take the opportunity that any discussion of ‘new media’ brings, go have a look at their kids playing Nintendo in the basement, and see it as something that could be a little more than a drain on the Christmas budget.

I’m back online. I’ve been doing finger weights. I’ve had a lot of sleep. There are 3 empty coffee mugs beside the monitor. Out of the corner of my eye I see the Queen Mother. She has an anti-tank launcher taped to the crossbar of her walking frame. A bald globe swings back and forth overhead. She looks left and right down a deserted intersection, undecided. The chrome on her walking frame catches the light. She hasn’t seen me. I swing around behind.

The Ultima Online website can be visited at: http://www.owo.com/ [link expired]. There are a slew of online gaming sites; one of the best, Heat Net, can be salivated over at: http://www.heat.net/ [link expired]. Get yourself some new skins, mod files (levels) and patches for your favourite games at http://www.fortunecity.com/underworld/quake/370/filez.html [link expired] (for Quake 2) and http://www.geocities.com/Area51/Dunes/6250/downloads/index.html [link expired] (for Dark Forces 2).

RealTime issue #29 Feb-March 1999 pg. 16

© Alex Hutchinson; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

You could never envisage all the camera has seen, countless images scattered at random in time and space like the fragments of a vast and ancient mosaic…you will never comprehend the totality of such a fabulous and excessive montage…

Scott McQuire, Visions of Modernity, Sage Publications, London, 1998.

It is hard to think of this year’s Dance Lumière program as a totality. So different were these shorts that I started to wonder what it is that characterises the “dance film.” This year’s curator, Erin Brannigan, spoke briefly before the showing, delineating 2 forms of classification. One of the categories is a performance which has been filmed, a dance documentation. Many of the films in this category were reminiscent of those Royal Shakespeare Company films of plays staged on sets. The setting is usually the original performance space, the staging the same as that for the performance. An exception to this was Scenes in a Prison (Jim Hughes, Graeme McLeod). This work was (re)located in a prison, admitting a plurality of perspectives upon the unrelenting nastiness committed by its “inmates.” Another notable exception to the staged paradigm was Falling (Mahalya Middlemist and Sue-ellen Kohler) which played with the temporality of the movement, turning the work into something quite different from live performance. Falling comprised a sepia tinted fractal of movement, progressing as if frame-by-frame, the fluidity of movement reduced to staccato images. What I loved about this film was the space for thought created in its snail-like progress. The rest of the filmed performances—Elegy, Body in Question, and Subtle Jetlag—were interesting because the performances looked interesting, not because of their being films.

The other espoused form of classification was the “Dance Film”, that is, a film specifically made with dance. One would expect these films to offer more in terms of a cinematic aesthetic. Perhaps so, but they certainly did not ascribe to the same cinematic values nor to the same interpretation of dance. Some of the films shared a sense of dancerly composition: Sure (Tracie Mitchell, Mark Pugh) showed a beautiful warp and weft of dancing bodies, and Dadance (Horsley, Wheadon, and Elmaz) a surreal 1930s play between visual art and dance. But others, such as Hands (Jonathan Burrows, Adam Roberts) and Greedy Jane (Miranda Pennell), involved urbane forms of movement which were carefully crafted and represented.