Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

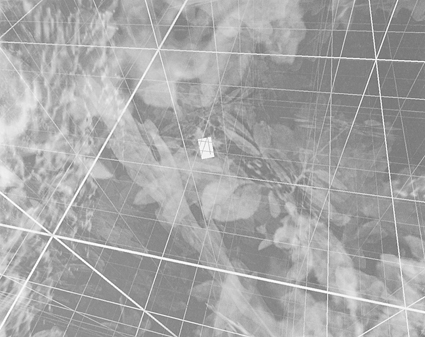

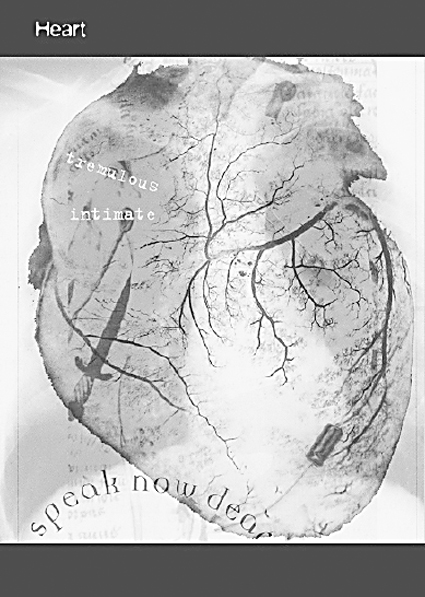

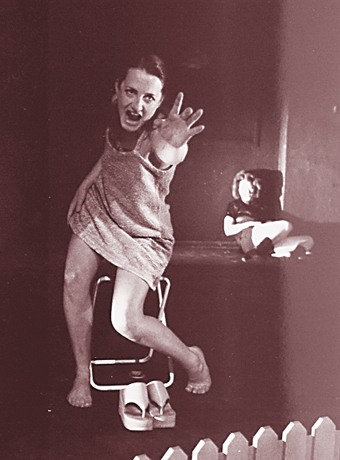

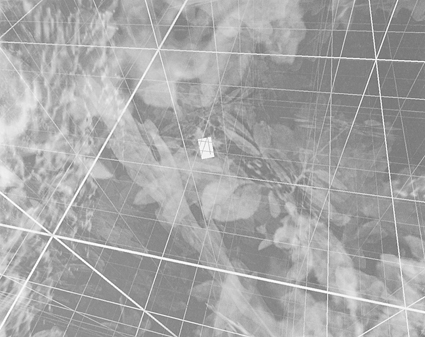

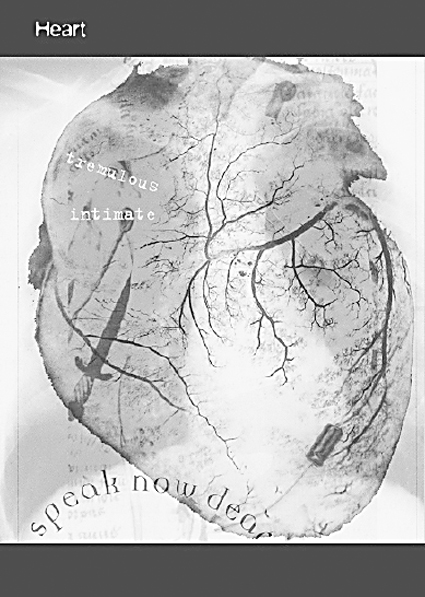

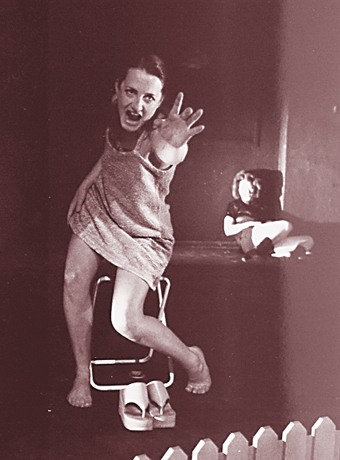

Char Davies, Forest and Grid, real-time frame capture from Osmose (1995)

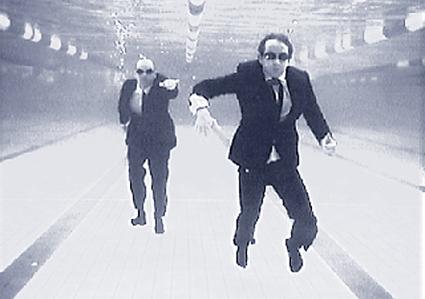

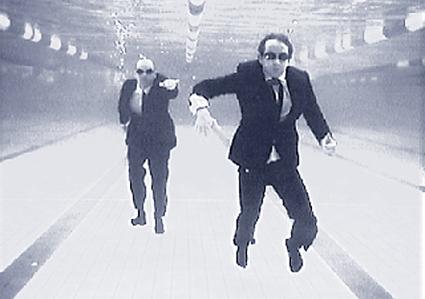

Based in Montreal, Canada, Char Davies is best known for her acclaimed immersive virtual environments Osmose (1995) and more recently Éphémère (1998). The works are notable not only for their exquisite translucent visuals and evocative soundscapes but also for their creative interface. In her immersive environments, the user, or more accurately, the ‘immersant’, does not just manipulate a mouse or joystick or touch and point with a dataglove, they are immersed in a virtual world where the body is the navigational interface. Immersants are strapped into a motion tracking harness and breathing and balance determine their movement within the worlds. There is a paradoxical freedom from the physical limits of the body as you float through the world on a meditative journey but this is coupled with an intense awareness of the body anchored by the breath. The works are both literally and figuratively captivating.

Char Davies likens this experience to the bodily immersion of scuba diving where the diver also navigates through body and breath control and the works certainly do share some of the characteristics of a fluid underwater environment. But there are also surreal, otherworldly aspects to the work which induce altered states of consciousness that are more evocative of dream states or the experience of meditation. The environments of Osmose and Éphémère are alternate realities, worlds of the imagination which follow the logic of dreams rather than the rules of real world physics. In real life you can’t float up into the sky or down through the earth. In Osmose and Éphémère you can do both.

Osmose is structured into a series of translucent shimmering world spaces but as well as its startling beauty, the work is also conceptually sophisticated and self-referential. The first virtual space experienced is a 3 dimensional Cartesian grid which dissolves to a clearing as the immersant starts to orient themselves with their first breaths. From the clearing the immersant can journey to a variety of world spaces including Forest, Tree, Leaf, Pond, Earth, Cloud, Abyss and Lifeworld. Underlying these worlds is an area of computer code and there is another upper level or layer of quoted texts which comment on nature, the body and technology.

Although her artistic iconography is drawn from nature and natural processes, Davies presents us with more than a virtual reality representation of nature; her work is a reconstruction of nature, a second nature, where we can see through the underlying grid and code that the environment is based on, and the conceptual overlaying of culture in the upper level of texts to the translucent visuals that explore the inner workings of natural forces and processes.

Like Osmose, Éphémère includes archetypal elements of nature (earth, rock, tree, river) but in this work the metaphor is extended to include bodily organs, blood vessels and bones. The work is structured vertically into 3 levels: landscape, earth, and interior body—each level moves through transformative cycles of germination, growth, decay and death and immersants can also ‘cross’ from underground river to bodily artery/vein. Each journey through Éphémère is different and, like Osmose, the experience is determined by the immersant’s breathing and balance.

In her online documentation of Osmose, Davies introduces her work with a quotation from Gaston Bachelard’s The Poetics of Space. “By changing space, by leaving the space of one’s usual sensibilities one enters into communication with a space that is psychically innovating. For we do not change place, we change our nature.”

In documentary footage of Osmose, the effects of this ‘psychically innovating’ experience is evident on the faces of people taking off their head-mounted displays at the end of their immersive experience. The common facial denominator is wide-eyed dreamlike wonder, some are moved close to tears. Most of them are almost speechless after the experience, those who could string a few words together beyond ‘wow, that was amazing’ compare the experience to meditation or to a religious experience. The phenomenological experience of the work appears to induce a contemplative meditative state which blurs the boundaries between inner/outer and mind/body. “The experience of seeing and floating through things, along with the work’s reliance on breath and balance as well as on solitary immersion, causes many participants to relinquish desire for active ‘doing’ in favour of contemplative ‘being’” (Char Davies, “Changing Space: Virtual Reality as an Arena of Being” in The Virtual Dimension: Architecture, Representation and Crash Culture, ed. John Beckman, Boston: Princeton Architectural Press, 1998).

The introduction via the means of virtual reality of new experiential spaces opens up the possibility not only of new experiences but new modes of experience with the potential to change human nature itself. Comments Davies, “Such environments can provide a new kind of ‘place’ through which our minds may float among three-dimensionally extended forms in a paradoxical combination of the ephemerally immaterial with what is perceived and bodily felt to be real” (ibid). Although science fiction literature and film has started to sketch out this terrain, in the real world we are just starting to glimpse some of the possibilities of these new technologies. Exactly what the long-term ramifications of this will be for human nature is a topic that will be of increasing importance as we move into the virtual reality domains of the 21st century.

Char Davies’ visit to Australia in June-July 1999 was hosted by Cyber Dreaming, an Aboriginal multimedia production company based in Queensland. In Sydney, dLux media arts presented Davies’ keynote address at Flashpoint 99 architecture and design conference, University of NSW, July 12. More information about Char Davies’ work can be found at http://www.immersence.com/

RealTime issue #34 Dec-Jan 1999 pg. 14

© Kathy Cleland; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

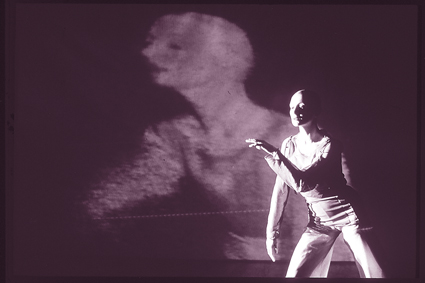

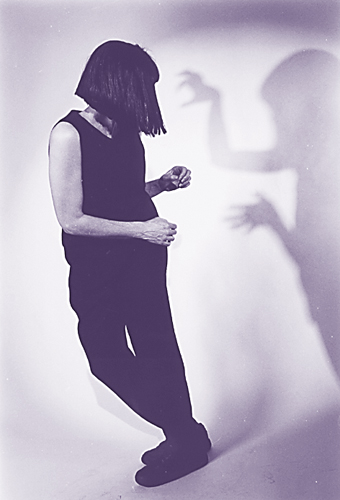

Norie Neumark & Maria Miranda Dead Centre: the body with organs

A travelling resonant hum, skittering tongue sounds, voices speaking, slowed clunking loops, an accordion chord. Amanda Stewart orbits the room, darting behind translucent printed hangings, through reflected shafts of dataprojection, then approaches the double-miked stand in the centre of the space. She scatters streams of sibilant, half-voiced words and word fragments around; with a small sideways head-movement across the microphones her voice pans across the room. The clusters of humming and flickering sound continue, shifting steadily, and Stewart improvises a counterpoint with them; at one point the live voice is absorbed into its recorded double, indistinguishable, before the textural clusters change again. She swivels a nearby monitor, showing animated sequences of figures, lines of text, abstract diagrams which match the projections bounced around the walls. The odd word is spoken whole, or repeated—“the liver”, “nineteenth century”—then dissolves again into fragments of mouth sound. Stewart leaves the mikes and circles the room once more, then slips silently out the curtained doorway; her audience murmurs, and disperses to inspect the installation.

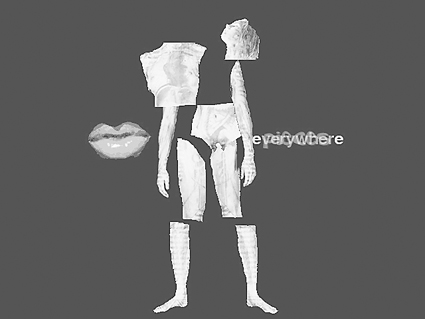

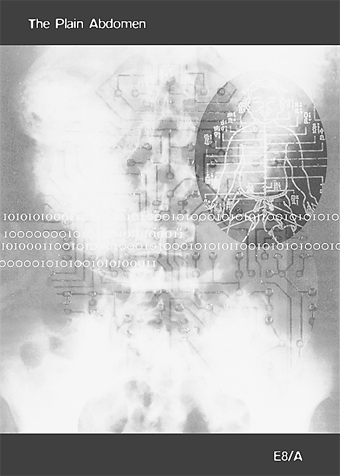

The physical components of the installation form another mass of overlapping fragments; Maria Miranda’s dense, fleshy layerings of anatomical diagrams and circuit boards hang in transparent sheets at either end of the space. A bank of mirrors breaks the computer projection into reflected, twisted strips which intersect with the transparent hangings and form fuzzy mosaics on the walls—a nice change from the normally monolithic new media screen. The animated material, also by Miranda, mixes lush paint or pastel textures (like those that gave Neumark’s interactive Shock in the Ear its distinctive visual style) with more hard-edged, machine-like flickerings. Taken in installation mode, the textural, multi-channel soundtrack gels well with the visual stimulus; things begin to link up with the spoken phrases and their discussions of the cultural specificities of bodily organs. Stand on the large plastic pad in the room’s “dead centre”—where Stewart performed—and a steady throbbing grows and seems to advance along the space. Precise sound reinforcement makes a difference here—the depth and spatial clarity of the soundtrack is a pleasure to hear. It integrates the room enough that it feels like a kind of scattered exo-body, one whose organs constantly shift and reform themselves, but still hangs together.

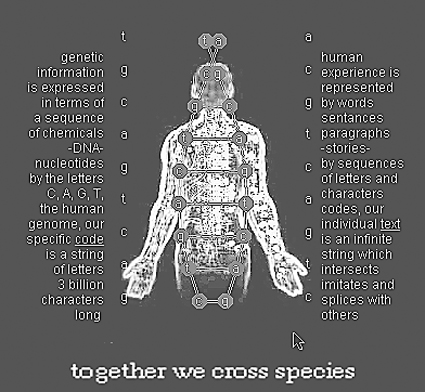

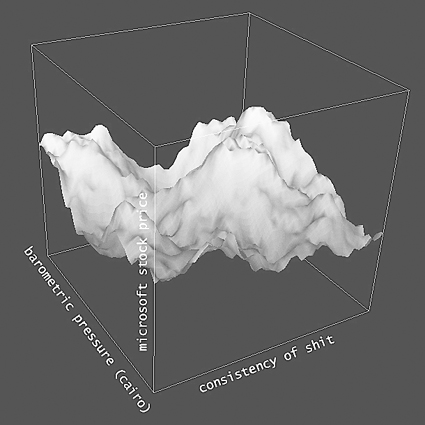

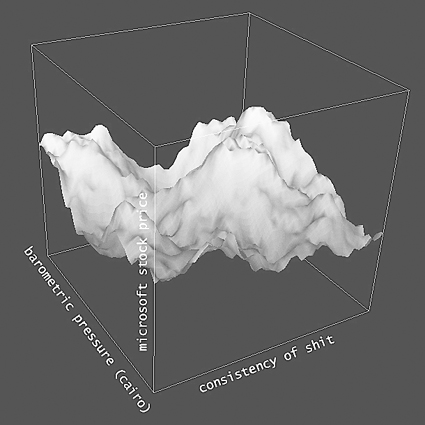

Of course it is organs, real and metaphorical, which are Neumark’s interest here, and organs of digestion in particular. At the core of the work is a correspondence that is only suggested in the installation: a notion of the computer as a digestive organ, a kind of prosthetic informational bowel (rather than a cyborg brain) that we use for processing email, images, sounds. The metaphor extends outwards into the work’s collaborative form: Neumark describes it as a kind of collective co-digestion, as Stewart’s vocal material trickles into Greg White’s low-end pulses, and Neumark’s soundtrack is redigested in Miranda’s visuals.

A likeable metaphor, and a continuation of a project close to the heart (so to speak) of much recent new media work—to reinvest mainstream cyberculture with the blood and guts of material things. In games like Doom bodies get splattered into an homogeneous pixelated goo; Neumark reminds us of bodies’ differentiations, and of their entanglement in cultural structures (hence the play on the Australian “dead centre”). The installation suggests a cyborg body, but not the dystopian one where the “meat” is nothing but a site for technological renovation. Here, the machines are assimilated by the body and its wandering metaphorical organs.

If there is something dissatisfying about the piece, it’s perhaps that these ideas don’t develop, but rather, remain elusive in the work itself, broken into metaphorical fragments and left for the visitor to reassemble. If a computer is a digestive organ, what value does it extract from its fodder? How do we tell an excretion from a vital nutrient? The metaphors pulse and grumble and flicker richly, but they stay indistinct—only spelt out in Neumark’s written statement. Perhaps this is only fitting since our own internal workings are just as elusive, offering us only the odd pang, gurgle or spontaneous emission as evidence of their operation. As Dead Centre points out, this leaves them open to personal and cultural reconfiguration—shifty, slippery innards.

Dead Centre: the body with organs, Norie Neumark and Maria Miranda, with Greg White and Amanda Stewart, The Performance Space Gallery, Sydney, July 9-22

RealTime issue #34 Dec-Jan 1999 pg. 17

© Mitchell Whitelaw; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

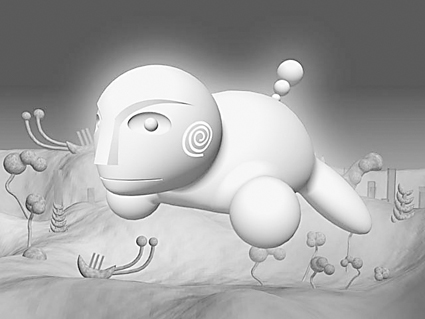

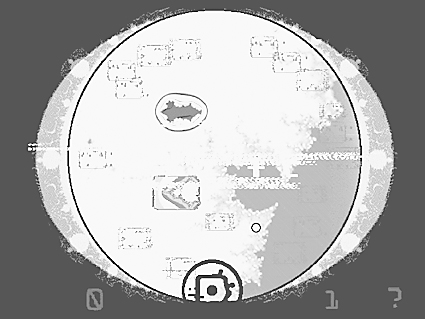

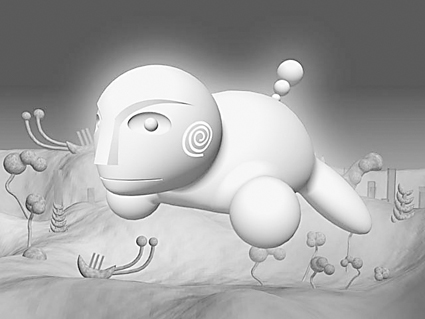

Troy Innocent, Iconica, Byte Me

An atavistic shudder went through the suddenly-silent crowd. We ‘knew’, of course, we all ‘knew’, the same way everyone always knew already about The Crying Game. But now someone had come out with it and it was discomforting.

We’d done the rounds of the exhibition space and chuckled knowingly at how the art (full of sound and furious interactive multimedia) was so loud we couldn’t properly hear the artists and commentators talking about the art. We’d been patient through the setting up of laptops and the inevitable irruptions of screensavers into Powerpoint presentations. We’d heard some data-packed, sardonic, erudite, passionate, whimsical, burnt-out and solipsistic presentations from artists and critics, and been given a pragmatic info-bite and pitch by Cinemedia on funding practices and venture capital.

And, then, this accidental, or blasé, revelation. “Someone in a car yard in Richmond,” I think it went.

“Fashion designers do it too”, someone said dismissively afterwards, picking over the fallout at a natty Bendigo pub. What crap. Did you see what Jon McCormack did? He’s not a natural nerd you know, he had to teach himself the code and put it all together himself, came up with the algorithms to make it work. And Troy Innocent, making up his own complex comprehensive iconic language and idiom with which his artificial creatures and their human watchers can communicate. For my money and long car ride, he’d obsessively ex nihilo created one of the most inventive and engaging of the exhibits dealing with the widest repertoire of issues in the most concentrated space.

Anyway, we’d had Darren Tofts being Darren Tofts, doing laser-scalpel analyses of the experiential (is it like a TV-flow? what’s ‘intermedia’? are artists outstripping critical idiom?) side of new media, with its recombinant formats dramatising the techno-human interface with a poetics of uncanny, defamiliarising constructivism via bricolage with found object metaphors. In one of the most useful analogies, he phrased the symbiosis of visual/aural and textual as working like the wave and particle theories of light. And Jon McCormack critiquing technology as utopian dream with his pseudo-realist burlesque on the function and idea of the scientific/museum diorama as didactic cinematic spectacle (Julius Sumner-Miller does 3D) taken over by multimedia as the prime, hyped, ‘natural’ successor to olde-educational spectacle.

And Peter Hennessey, who satirised the Oedipal identity crisis of ‘new’ media, dubbing it ‘pubescent’, sending-up the endless search for provenance or paternity among ‘old’ media, deflecting legitimation onto context, reflexivity and simulation, bemoaning prescriptive formulae and—gossip-wise a great step sideways—announcing the irrelevance of ‘authenticity’ as criterion. Kevin Murray spoke on insects and cyborgs as design allegories of social trends, over-generalised psychology, economic rationalism, privatisation, political amnesia and civil anomie. And James Verdon on the recursive DNA-looping of memory, narrative, memorial and camera/monitors by which artwork can respond to your movements.

But it was Patricia Piccinini who came out with it. After an amusing discussion of her work, including the ‘car nuggets’ (miniaturised offcuts from automobile iconography, smoothly sculpted and shiny), a Coca-Cola-ish bubbling-spring animation and a video installation of rust-done-to-look-like-a-world-globe, someone asked how she did it. Apparently the nuggets are done by carpenters and spray-painted by someone in a Richmond car yard. The moving images are by Drome.

Now, without wanting to get all Giles-Auty on you, isn’t there a teensy issue here to do with credit, acknowledgement and transparent processes (to say nothing of authenticity or intellectual property, which is always a good idea in such pro-pomo but ethically-fraught circumstances)? No mention of Richmond spraypainters on the gallery wall, or in the forum paper. If someone hadn’t asked, would we ever have known? Should we? Of course you’ve got the Koons defense, the canned-Warhol argument about artists who conceptualise but don’t do. It’s an argument that joins the dot-points: artisanship, craftsmanship, corporate-art delegation, design and directing. That’s ‘directing’ as in ‘storyboarding’ videos/animations and ‘blocking out’ sculptures/installations with ‘plans’ (trans. sketched outlines for someone else to actually construct). Kevin Murray pointed out that Piccinini’s sketches were beautifully done, artworks in themselves.

So, yes, a bit like a fashion designer, though those are usually ex-draftspeople who have apprenticed themselves in most areas of craft before they become hands-off designers (and some never do). Also a bit like Darren in Bewitched. Or Samantha, for that matter.

And disturbing, like the other issues deftly raised at the forum. I’m still arguing about it.

Byte Me, curator Anonda Bell, Bendigo Art Gallery, Forum, Saturday 24 July 1999.

Just as with the NXT event in Darwin, and MAAP99, so Bendigo Art Gallery’s Byte Me is an important addition to a developing regional awareness of and participation in new media nationally and internationally. Here the key participants were Melbourne artists and commentators in exhibition and forum. Esta Milne comments in experimenta’s online periodical MESH on the same issue raised here by Dean Kiley in her article “Nameless things and thingless names: A review of the Byte Me Forum.” MESH 13: Cyberbully. Eds.

RealTime issue #34 Dec-Jan 1999 pg. 17

© Dean Kiley; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Nalini Malani, India, born 1946, Remembering Toba Tek Singh, 1998 (detail), video installation

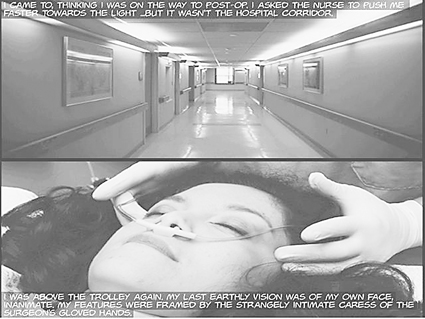

Black and white video images of an old woman in an uncertain landscape. She wears the standard peasant dress with the scarf worn as a shroud. Close-ups of her eyes mingle with land and water, tears, younger women. Are these images from memory, herself as a younger woman? Is it a testimony to unlived lives?

I don’t know if the old woman played by Joyce Rankin in Louise Drinkwater’s moving electronic remembrance is the real subject of this piece but in a way it’s not the point. It is a piece which generates effects of memory and maybe even a bit of nostalgia and, not surprisingly, made me think of my own grandmother, long gone.

This is a Recording is a votive machine repairing “the web of time” as Chris Marker says in Sans Soleil. It is also a deserving winner of the 5th Guinness Contemporary Art Prize for tertiary art students. The Sydney College of the Arts should be congratulated for producing student work of this quality and maturity.

Iconographics: Antidotes to compassion fatigue

The video installations of the 5th Guinness Contemporary Art Project show how powerful good video art can be when it is presented properly. The curatorial focus and integrity of vision here are everywhere in evidence in Voiceovers which presents the work of 4 prominent figures in contemporary video art and suggests that this kind of art has the potential to effect the rescue of our tired media and our exhausted senses and re-humanise aesthetics as an experience of the body.

Nalini Malani’s Remembering Toba Tek Singh uses a triptych of video projections showing images of the atomic bomb blasts at Hiroshima and Nagasaki—the last orgiastic scenes in the final act of mass slaughter which closed WWII—framed by videos of 2 women holding ends of the same sari. In front is a grid of steel trunks containing bolts of cloth and small video monitors showing amongst other things images of the clear blue sky and the act of giving birth. The voiceover mentions bombs called ‘Fat man’ and ‘Little boy’ and the obscene ‘humanisation’ of nuclear war. Malani also notes that ‘Shakti’ (living energy or life force) was the name given to the Indian atomic bomb tests in the 1970s. Her point is, as the voiceover says, that in “using language as an anaesthetic, feeling dies.”

This installation is designed to counter this loss of feeling, to resist the anaesthesia which alienation induces and to act against the destruction which the dominance of military aesthetics (cf. Virilio) renders banal in our culture. The Benjamin resonance is unmistakeable. In Walter Benjamin’s classic essay of 1936, “The Work of Art in the Age of its Mechanical Reproducibility”, he attempts the rescue of both technology and the senses from the fascist aestheticisation of politics and its spectacles of seductive power. He calls for a critical use of technology to counter the crippling “self-alienation” of mankind which he says has “reached such a degree that it can experience its own destruction as an aesthetic pleasure of the first order.” As the smart missiles with cameras attached rained down on Belgrade, who has not participated in this thrill of the destruction of bodies?

But Malani’s polemic is also gendered and after spending any time with her installation the feeling is that the very existence of these weapons is a persuasive argument for feminism, a point underscored in Shirin Neshat’s Turbulent, a critique of the compulsory silence of women in public space in Muslim societies. A simple opposition is generated with the 2 large screens en face. One contains the image of a man singing to an all male audience and then looking across the space at the image of a woman wrapped in a chador, who sings in turn. But her song is incomprehensible, a vocalisation of the body or a kind of semiotic chora. She performs a presymbolic message, running beneath and counter to the male dominated system of generating cultural meaning. For the detail of this piece I recommend the catalogue text by curator, Victoria Lynn, which places the question of the cultural emplacement of women’s voices “at the heart of Voiceovers.”

The pop star of contemporary video art, Mariko Mori, does her own less visceral performance for video. Kumano generates an auratic distance between the audience and the personae she presents. These pieces, like much of her work in video and photography, play with iconographies and project a simulated sense of the sacred, eg in the pastiche of the cybernetic tea ceremony. In a sense she is updating the imagery of the spiritual with the cyber-chick at the centre. And why not? Her task is made easier by her telegenic presence and the skill of the armies of assistants who produce exquisite images. Ken Ikeda’s ambient music score for Kumano establishes the mood of contemplation while we watch this cheeky play of cyborg signifiers.

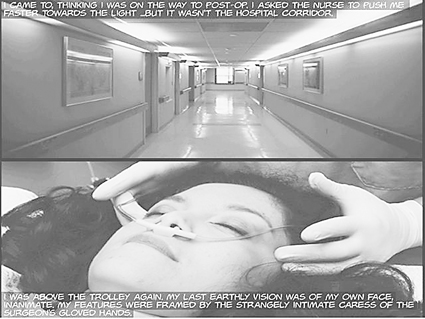

Lin Li’s voiceover to the video Soul Flight reassures the viewer about the images we see. Her naked body prostrate on a mountain top while vultures tear at piles of blood and meat which cover her is explained as the performance of the sky burial. This is a remarkable piece of intense performance making for video and a powerful re-enactment of a liminal ritual: in between death and rebirth, sky and land, soul and body. The piece is, if anything, too short. We move from the images of the body, flesh and birds to ‘Afterwards we had a cup of tea’ all in a few minutes. It is a mild but pleasant shock and another example of what critic Susan Buck-Morss says is crucial to Benjamin’s enterprise, the restoration of the sensory experience of perception to the field of Aesthetics so that the construction of the modern human as “an asensual, anaesthetic protuberance” may begin to be undone. This is a theme of the work presented in Voiceovers which makes it surely one of the most important recent exhibitions of video art seen in this country.

Voiceovers, The 5th Guinness Contemporary Art Project, curator Victoria Lynn, Art Gallery of NSW, Oct 8 – Nov 14

RealTime issue #34 Dec-Jan 1999 pg. 13

© Dr E A Scheer; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

East Timorese participants at Nxt Symposium

The first day of October is the first day of The Wet in the Northern Territory. And sure enough, Darwin experienced a night time shower after the evening opening of NxT. This multimedia symposium, like the several before in other states, set out to expose ways in which, in the words of the coordinator Mary Jane Overall, “artists have challenged, examined and grappled with technologies in ways never even considered by the corporate world.”

Hosted by the local office of QANTM (the Brisbane-based cooperative multimedia centre—CMC) in close collaboration with Geraldine Tyson of 24HR Art, this complex event involved many more sponsors and partners than the similar events organised by the Australian Film Commission (primary financial assistance for NxT was provided by the New Media Arts Fund of the Australia Council), and gave an overview of much that has occurred in Australia amongst those working with interactive multimedia and also single-channel multimedia.

Like a croc in the Harbour, Darwin bobs out of the waters of the Arafura Sea just enough to focus on the task ahead. It faces outwards—to the bush and to the ocean—and as entrepreneurial trader and fixer, responds selectively to the needs and aspirations of the scattered Territorians. The Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory, built on the foreshore, is a microcosm of the local diversity with stunning artefacts exhibited within its walls (happily the fantastic annual National ATSI Awards coincided with the NxT event) and outside under the breezy palms and fig trees, the Ski Club on one side and the weekly market and citizens gathering at Mindil Beach on the other. In the clammy air, close to the water and with The Wet due, Darwin epitomised the flux of events, both natural and human. Like the best conferences, the setting invigorated and the talking took off…

Inevitably, with so many artists from interstate and overseas who have been practising in the area of media arts for 10 years and more, history was the other setting. Paul Brown’s personal history included works by filmmakers Jordan Belson and the Whitney brothers, ex-painter Harold Cohen, Nancy Burson, Edward Ihnatowicz, Vera Molnar, Larry Cuba and many others. Coming up to the present he repeated the prediction that is now being heard more widely, that the internet should not simply be regarded as another entertainment medium but distinctly as an evolutionary shift. Amplifying Stelarc’s comments from the previous night (and indeed, the previous decade), the development of the internet can be seen as a direct extension of the human cerebral cortex and will lead us inevitably toward a prostheticisation of the corporeal frame, a process that began centuries ago and accelerates as telecommunications and nanotechnology entwine with the human genome—the wetware evolutionary phase.

Such a migration of consciousness translates for some politicians present, and Sally Pryor, as a need “for humans to control the computers.” In the CD-ROM, Postcard from Tunis, she developed a means of referencing another culture without it becoming a cross-cultural enterprise requiring open collaboration. Such a thread was a strong feature of the NxT symposium and was paramount at the Resistant Media space (programmed by Australian Network for Art and Technology) in the Ski Club premises, where a battery of online computers enabled the conference and visitors to continue to grow the cortex. Shuddhabrata Sengupta explained that in the context of the border war with Pakistan, the net offered access to discussion denied in the public spaces of India and, “like modern ley lines across the map”, used anonymity, or the threat of anonymity, as a telling component of contemporary culture effected by warfare. At the same panel session, Geert Lovink reminded us of the part the net played in the wars in the Balkans, relaying closed radio stations, establishing list syndicates and using the range of media in a tactical manner. If it’s possible to view wars on television from the comfort of your armchair, is it becoming possible to actually participate in violent struggle from the comfort of your own workstation? He maintains a distinction between net activism rather than net alternatives. Communication networks must respond to need and develop a political aesthetic. This is the site of engagement and intervention rather than that of an outsider logging-on to passively read the electronic newspapers.

Meanwhile, just across the sea in East Timor, the United Nations were mopping-up the militias, and Sue McCauley referred to the Free Timor website and others that had a large part to play in keeping exiles and the rest of the world directly linked to events. Sam de Silva emphasised the need for more tactical alliances between artists and campaigns, for websites to provide information countering the claims of corporate interests, and acting as communication points for popular campaigns such as Jabiluka.

Peter Callas showed an early 2-screen video work which, utilising footage from the Vietnam War, demonstrated the subtleties of irony in relation to race and the culture of militarism. The survey of his work fleshed out the complex ways in which the modern electronic cultures of the Japan he encountered inexorably plotted the advances of cybernetic prostheses. He had created electronic horizons in cities like Tokyo where the landscape horizon had long been obscured.

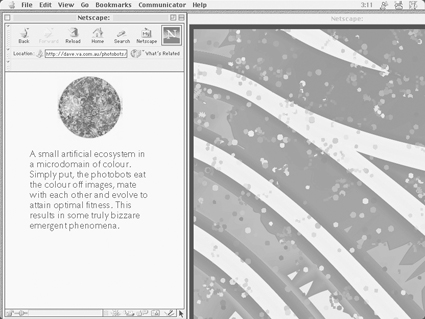

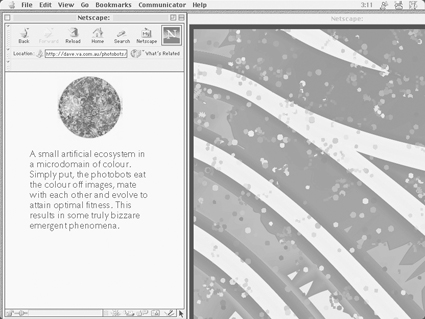

“The computer as an intelligence amplifier” was how Jon McCormack characterised the human evolutionary stage, though his own work concentrates on a move away from carbon-based life forms to those based on the life-synthesising silicon chip. In the pursuit of complexity from simplicity, he demonstrated the ‘Evolve’ interface he has developed which may become a market item offering the experienced user ability to create Artificial Intelligence environments through this code-writing software.

Josephine Wilson described online writing communities, including Cipher (www.ensemble.va.com.au), her recent online project collaboration with Linda Carroli. Josephine Starrs previewed the new CD-ROM she produced with Leon Cmielewski: Dream Kitchen takes the Doom gaming conventions into the kitchen where, equipped with egg flips and other utensils, various 3D animation horrors are dealt with in hilarious style.

“The updated version of Cyberfeminism is more about networking, webgrrrls, geek girls, FACES, OBN, online publishing, career prospects, list servers and international conferences,” stated Julianne Pierce in surveying the work of VNS Matrix, “…to get ahead you must control the commodity. Information is political, it’s a weapon, and the more knowledge we have, the more powerful we are”.

Yolgnu knowledge, from NE Arnhemland, has been the longtime study of Michael Christie. He described the issues surrounding the work at Northern Territory University “to incorporate Yolgnu theories of language, identity, intellectual property and the negotiation of knowledges into the university teaching structure.” This has been pursued through a number of multimedia projects aimed at producing study materials.

Such cross-cultural projects have been a success. In the words of Kathy Mills, the prominent Aboriginal spokeswoman, songwriter and poet of “greetings, respect and language”: “Balanda (white fellas) don’t listen carefully or respond with appropriate structures…” Her work has been concerned with addressing such shortcomings in the health industry.

Staff from Batchelor College discussed and showed work derived from the adaptation of electronic technologies into the Indigenous education environment of that campus, in particular, digital archiving approaches to stories from the communities.

East Timorese refugees in Darwin were hosted throughout the symposium, utilising the online facilities and, during the final emotional session, immersing themselves in Michael Buckley’s CD-ROM collaboratively made with the Melbourne Timorese community. East Timor, Culture, Resistance and Dreams of Return allows a “rich plurality of voices” in a “social interactive documentary” in which the developer had more of a curatorial role in the design and production rather than being its author or director.

The plurality of voices online and in other public spaces was celebrated throughout the NxT event in a spirit of mutual respect for language and cultural difference. However, the impetus of rapid advances into digital culture during the decade by Australian artists is in danger of dissipation through reductions in levels of infrastructure support. The increasing babble from websites is daunting to most potential audiences. Whole areas of research as well as artefact are denied beneath the weight of Microsoft-style marketing. The wetware alliances between artists, scientists and technologists, well established overseas, are hardly heard of here. Indeed, is there a place in evolution for 3D animation?

The NxT symposium showcased a significant national record and described innovation in The Top End setting. The next event needs to be more risky and project into the future with an image of multimedia arts as a form of ubiquitous social interaction.

NxT Northern Territory Xposure Multimedia Symposium, Darwin, September 30 – October 4.

RealTime issue #34 Dec-Jan 1999 pg. 18

© Mike Leggett; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Interacting with a CD-ROM is, at its most basic, an inane exploration of someone else’s digitally constructed space. In Linda Dement’s CD-ROM In My Gash, the process of navigation is as penetrative and confronting as the work itself. The user, and it is definitely a user here, has a sense of control that borders on sadism, voyeurism and rape. Each click of the mouse leads to a further wound, slit or cut in a virtual skin. The breaking or intentional rupturing of this pristine surface transgresses a natural boundary between the fluids of our bodies and the outside world. In this work there’s almost blood on the keyboard.

Incorporating chilling sounds, bits of video footage, photography and extremely beautiful animation, the work is a direct confrontation with female disembodiment and sexual horror. The point of entry is the “Gash”, slang terminology for vagina, but also representative of a bleeding slit or wound. The user explores the “narratives” of the character LYING UGLY MESS BITCH by entering 4 different Gashes. The directions are simple: “Go Left”, “Go Right” and “Go In”. The process of entering this gaping, bleeding Gash is not an easy one. It reveals fragments of memory, of the pain and the horror contained within. She’s a young girl. A Dirty Whore. A Junkie Masochist. You journey, as if by internal camera probe, through the landscape of the Gash, triggering images and sounds. Flowers, syringes, cigarettes and metal spikes fade in and out of the screen. The sounds are of severing and tearing, desperate pantings and blood tingling wails. The video sequences are evocative of surveillance footage and clandestine filming. Encounters with a bad cop, trashy hotels, stabbing rages and blood drenched bathrooms.

As in a razor blade to the flesh, Dement seems to slice through the physical boundary existing between the screen and the self. Using the sterile mathematical coding of computer software, she has managed to create a totally visceral, ‘wet’ interior realm. The surfaces are slimy and shiny. Sometimes bleeding, sometimes not, there’s a sense of a never-ending secretion. She overturns notions of a ‘nice’ cyberfeminism; being explicitly female but overtly non-erotic, The Gash has been dismembered from the female body. It is now a portal of memory. And it has reclaimed the corporeal.

In My Gash is not easily accessible. Currently awaiting classification, and with the recent draconian net laws, Dement’s work would find it hard to exist on a local server. Sold, with an R-rating, it would fail to work as a satisfactory form of porn. However, In My Gash is a phenomenal piece of digital art. It may soon exist in a gallery space as her previous Cyber Flesh Girl Monster and Tales of Typhoid Mary have. But the real interest lies in whether it’s actually taken home and played along with the not so life-like Lara Croft.

In My Gash was produced in association with the Australian Film Commission. The CD-ROM launch was presented by dLux media arts at the Museum of Sydney, August 29.

RealTime issue #34 Dec-Jan 1999 pg. 14

© Joni Taylor; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

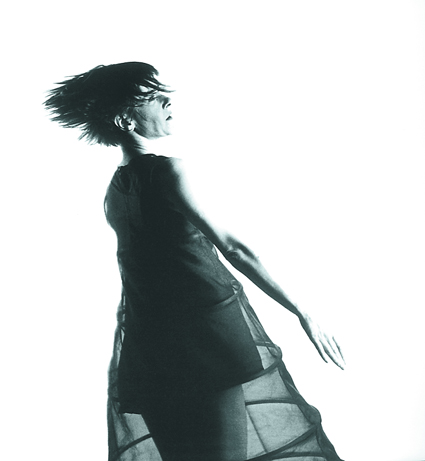

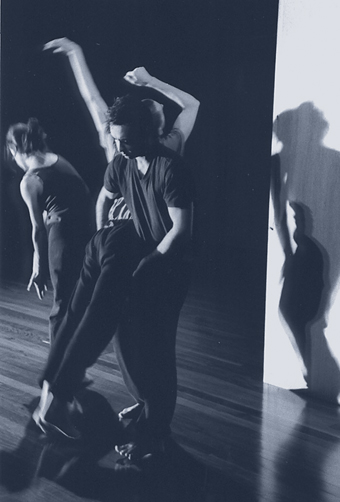

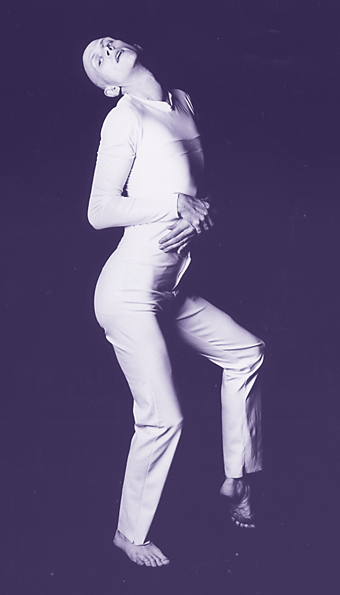

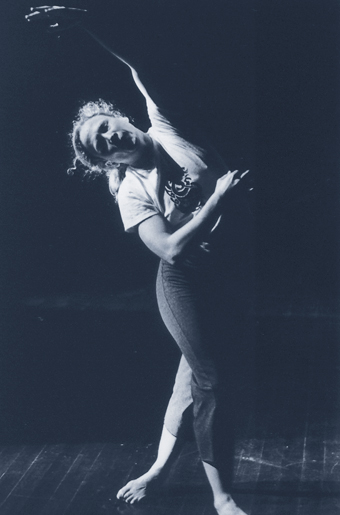

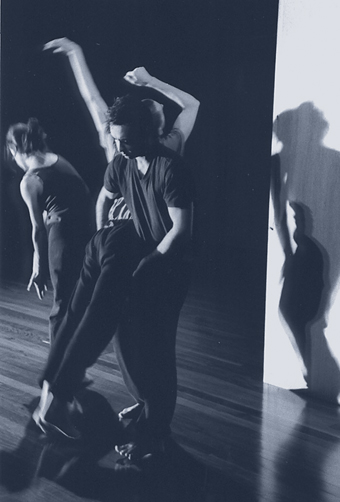

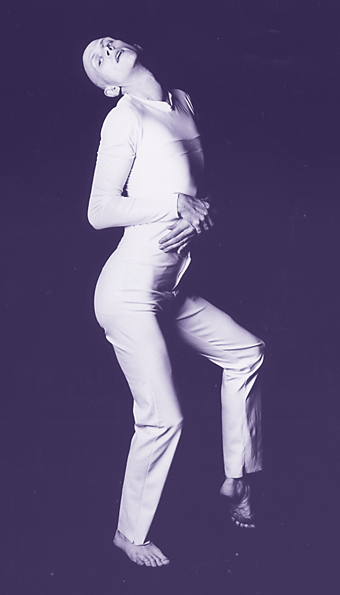

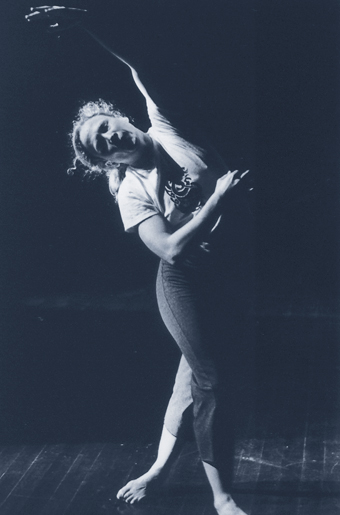

Alice Cummins, No Fixed Point

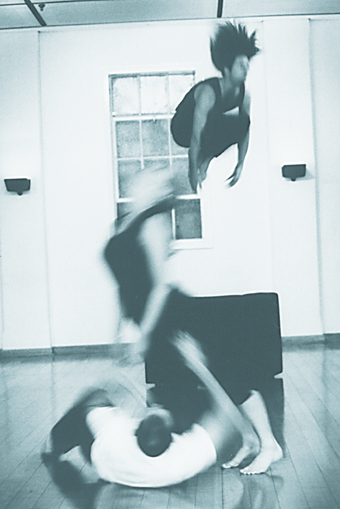

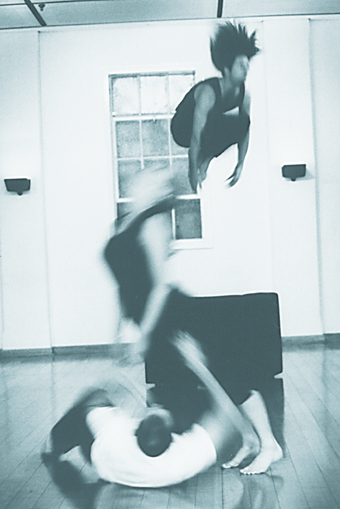

photo Andrew Beck, X -Events

Alice Cummins, No Fixed Point

There is an Old Law (God knows where it comes from) that says genres cannot be mixed. Yet, it would seem that the post-Star Wars audience demands that genres be mixed in a big way. So why is there so much policing of the boundaries in foyers around the land? Why is there always a little panic when dancers begin to speak? Perhaps it is something about the limitless intelligibility of rhythm and the abstraction of dance that sits as a burnishing trace element in the minds of the punters and irks them when genres are mixed. But genres need to be mixed. To know the law, we need to test the limit of the law.

Dancers are Space Eaters, the third biennial festival of contemporary dance at PICA, tested a whole clump of limits. Despite the attention to the issue, dancers using spoken text was not really a point of anxiety for this well-balanced festival. There was a strong blend of dance films, forums, performances, Q&A sessions, informal drinks, workshops, overseas guests and local artists with good attendance that created a buzz. A healthy blend of brilliant, promising, stupid, boring, inspiring, witty and contemplative work challenged established orthodoxy. One of the biggest challenges to dance earnestness came in the form of the new genre of stand-up-dance routines.

Grishia Coleman (a former member of the Urban Bush Women) one of the workshop teachers, volunteered a cheeky work-in-progress from NY called Modern Love. This was apparently a selection of scraps and vestiges from her a cappella group’s performances which are terrific, I am sure. This solo performance, however, did not amount to much more than bits of ‘choreographed music’, pseudo-sci-fi-mic jabber, a bit of cello, a pinch of Cab Calloway and a tantalising refusal to dance. However, Grishia did advance the dull dance/text debate by theorising the possibility of incorporating movement, music and song in an integrated whole—I only wish I’d seen it in practice.

Rakini’s R.E.M (Rapid Eye Mudras) were by turn titillating, captivating, thought provoking and yes, she did dance, and I thought how much can be said with just one swirling hand. Yet it was her text that made this a very funny performance. Indeed, if a common theme did emerge in the 3 weeks of this festival, it was the place of stand-up, shimmy-down, movement-comedy in postmodern dance. It all went beyond burlesque and into off-the-cuff, witty soft-shoe one-liners. There was no need for the safety of parody. Strange Arrangements and Sete Tele & Rob Griffin were hilarious. But Wendy Houstoun is the Woody Allen and Dawn French of solo movement theatre.

Happy Hour was an incredibly exciting stand-up site specific performance at the Fuel Bar. Houstoun became barmaid then barfly, bouncer then blousey raconteur in a precise observation of the narrative arc of a drinking session. Happy Hour is made up of all those meaningless fragments of bar room crapola—it is an essay on loneliness, petty stupidities, and poignant clichés. “The artist who wrote this song is a fucking genius” is repeated again and again, spilling the uncanny madness of drinking intimacies across the sodden floor. “It’s just rubbish!” says Houstoun in her perfectly pitched quiet voice (that insinuates this is not a performance), as she points to an ashtray or the performance or what we may think of her performance. Her twisted idioms brim with double shots of humour that gradually transform into strangely insightful mini-tragedies as the perspiration drops slide down the glass. Here there are no questions about the text/movement brew—it’s a heady mix. It is performance at the limits. The audience didn’t know these limits or where the end was—well it was at a Peter Stuyvesant after unceasing applause.

Melbourne’s Trotman & Morrish gave us Avalanche, for the first 10 minutes a sublime dream of cardboard box minimalism taped with pregnant poignancy. Beautiful boxes. Great lighting. Unfortunately, the sublime dripped into the soporific and then into a yawning disappointment. Although along with Morrish, I too fetishise cardboard boxes, his stand-up box-kissing routine did not explore the full eroticism of a big, clean, hard cardboard box. The movement caused no groundswells and did not articulate anything new or old or witty or scopophilic.

Alice Cummins and Tony Osborne’s No Fixed Point was just that, an endless slippery chain of moments, movements, phrases, fragments, passages, blurbs, bits and jokes. I have never before seen so sumptuous a performance retrospective. This was a tantalising journey exploring the artists’ favourite fragments from their solo and collaborative works over the last 9 years that for me have set the standard (but not the limit) for the genre. The chronological segments of the 7 works slid into a cohesive, dynamic unity and allowed an insight into 2 extraordinary performance careers. The extracts from No Fixed Point (1991) at the beginning of the evening looped piquantly with the new work The Perfect Couple (1999) devised specifically for the festival. The measured mad chase, passion and release of the first piece flowed into the desperate possessiveness of the last. Both performers displayed exceptional simplicity and pure madcap. For both the devoted audience and the performers it was a highly emotional evening, rare in this unsentimental city. It may have been prophetic that in tackling the difficulty of recreating old works, Cummins and Osborne signalled new beginnings. (And have left Perth for Sydney. Eds).

A weekend of 20 or more dance films and videos was an excellent and rare introduction to contemporary choreographers, many outside Australia—where this genre is more common. It’s hard to tell in what order these video performances were made—stage and then video or self-sufficient films with movement. Probably a healthy confusion. My favourites included the 2 sexy and robust pieces by Cholmondeleys and the Featherstonehaughs, Cross Channel and Perfect Moment (great art direction); Gravity Feed’s strangely affecting Bridge of Hesitation and The Welsh Men of Canmore’s inspiring Men, filmed in the Rockies with old fellas shaking more than their tail feathers.

But the 2 most powerful, voluptuous and mesmeric films were DV8’s Dead Dreams of Monochrome Men (UK 1989) and Iztok Kovac’s Vertigo Bird (Slovenia 1996). They were erotic in wildly different ways but both focused on the rough trade flat out cool passion of the scrambling escape from concrete spaces. A pregnant woman dancing hard on harder tiles and men hitting hard dance club walls even harder. These were visceral, explosive, full-contact ruminations into social spheres and hard body politics that left me screaming for more. They were even better on second viewing. Dancers are Space Eaters is a vital, edgy festival of contemporary genre-busting that rocked my boundaries.

Dancers are Space Eaters, Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts, October 18 – November 6

RealTime issue #34 Dec-Jan 1999 pg. 31

© Grisha Dolgopolov; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

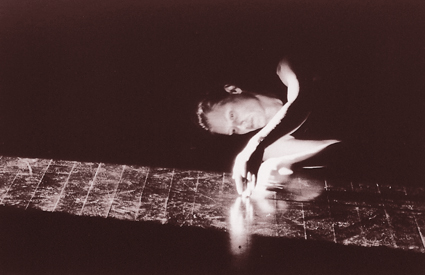

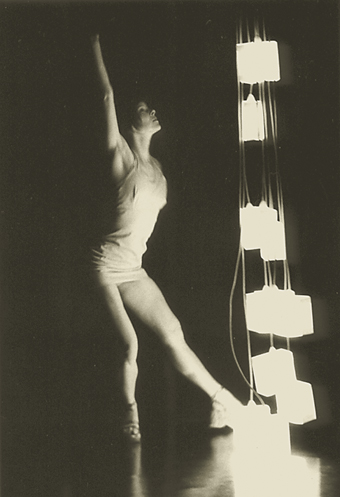

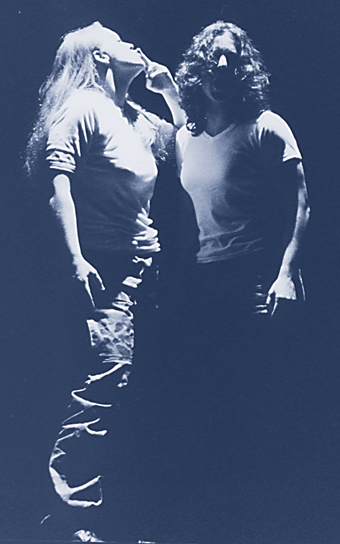

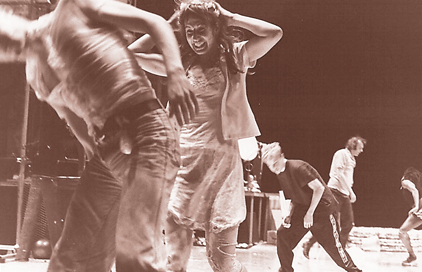

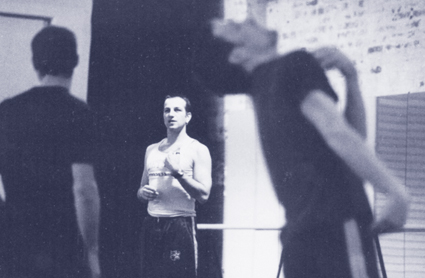

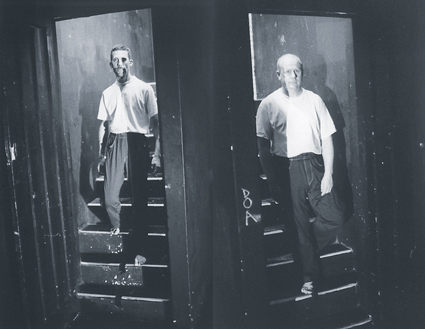

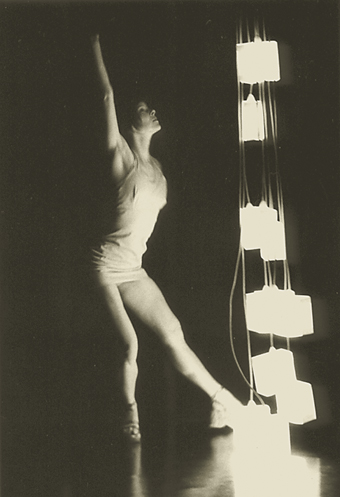

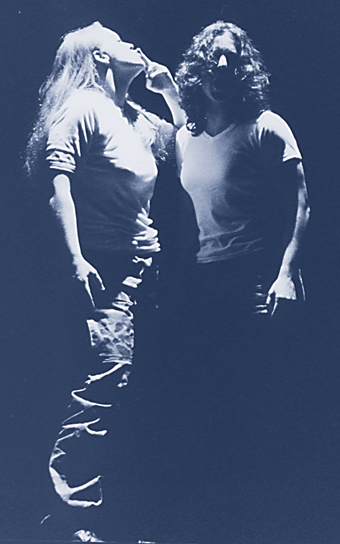

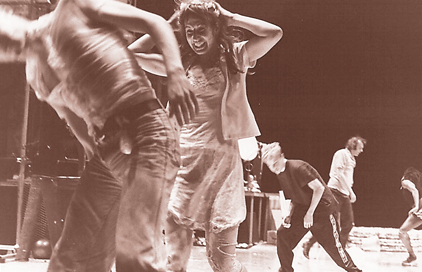

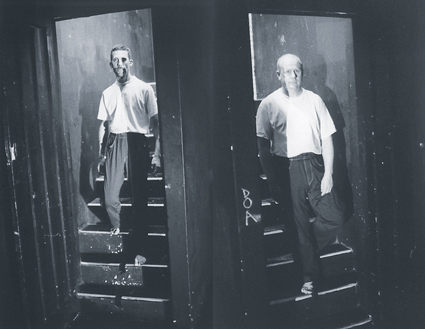

Wayne McGregor, Random Dance Co

photo Michael Taylor

Wayne McGregor, Random Dance Co

Wayne McGregor is a London-based choreographer and performer whose company, Random Dance Co, has a residency at The Place. He has been commissioned to create works by companies as diverse as Shobana Jeyasingh Dance Company and the Birmingham Royal Ballet and has also done extensive choreographic work for theatre companies, film and advertising. He was one of 2 choreographers (the other being John Jasperse from the US) conducting workshops last July in Melbourne for Chunky Move’s Choreolab. The project attracted a broad range of participants including Michelle Heaven, Shaun McLeod, Kate Denborough, Alan Schacher, Sarah Neville and Fiona Cameron. I spoke to Wayne MacGregor halfway through his workshop.

EB How does the Choreolab model for this type of workshop compare with others you have been involved with overseas?

WM There are very diverse choreographic laboratory schemes in Europe. For example, a mentor might come in and work with choreographers and set tasks, and then they work with a group of dancers and that is evaluated—that’s quite a traditional model. Then there might be a mentor who works with a composer and you, as the participating choreographer, have to work with their kind of collaborative choreographic processes. Because I knew it was going to be quite a diverse group of choreographers here in Melbourne, I thought I needed to hone in on principles I work with which still give them enough scope to apply to their own work—a sketch of ideas that they can then take and develop in their own choreography. Some of those principles have just been movement-based interventions generating language and content for dance, and some have been formal concerns—how is it that you structure your vocabulary into a coherent language that communicates with an audience? And we’ve worked with technological interventions that are either computer, video or film-based to give a different perspective on ‘action’ and then develop that choreographically. For example, I have a 3D animation programme called Poser which I’ve used to create some choreography on the computer that has then become a resource for stimulating other choreography. We’ve also worked with digital film to look at the possibility of genuine retrograde—filming something and then looking back at it in slow-motion reverse and re-learning it, but still maintaining the original kinetic information.

EB How did you find the participants’ contributions to the workshop?

WM One of the reasons I like doing these workshops is because I’m not like this great choreographic master coming around and telling everybody how to do it, but because it’s a genuine dialogue you always learn from. For instance I might set a choreographic task or idea, and the participants’ practical solution to the question is completely different to mine. And I’ve really found that with this group which has been interesting for my choreographic development.

EB These types of workshops are still very rare in Australia—we don’t have a great tradition of choreographic workshopping or mentoring. How important do you think this sort of thing is for choreographers?

WM I think they’re completely vital. I don’t think it matters what stage of choreographic practice you are at, if you’re really experienced or haven’t done very much; an opportunity to research and develop outside your own practice is completely critical and that’s why I still keep doing them. I’ve recently done a choreographic workshop with Bob Cohan in London where he mentored me for 2 weeks. You have to choose the right time to do it for yourself—in the middle of creating a new work may not be the right time to do a choreographic research project with someone else, although sometimes it might be. If you don’t have opportunities to extend your process you become very myopic in your approach, and your work becomes very habitual.

EB Is there any difference that you found here in Australia—any qualities that seem unique?

WM There is definitely a hunger for the information and for giving things a go—a really positive attitude to that. I think it’s also clear that the people hadn’t really done that many choreographic workshops because the kind of analysis—the ways in which you talk about, evaluate and positively criticise the work—perhaps wasn’t as forthcoming as in other places where they’ve had a lot of experience at doing that. I think it’s a very hard thing—not only talking about your own work but somebody else’s in that kind of context. And I think the more we go on this week the more vocal they are becoming. Lots of people position themselves in relation to work and say they either like it or don’t, but this is about looking at the work in relation to the task and to see how far we’ve gone in fulfilling it.

EB How did you learn your choreographic skills?

WM I did a 3-year dance degree which was primarily focused on choreography and it really was a kind of ‘craft’ approach. So it wasn’t so much about innovation in relation to language but about the difference between form and content and how you structure language; a formal approach. It was almost like music training—a technical approach like music—where once you’ve got all that ammunition you can really subvert it and explode it. So, I did that and then I was at the José Limon School in New York and while I was there I was able to participate in a range of choreographic workshops with a lot of very different choreographers working in New York. I think the best way to learn about choreography is by doing it and that’s what Forsythe has written—that the only way to master choreography is through practice.

EB But here there is the economic problem of affording the bodies to work on and the space to work in; the opportunities to choreograph are few and far between for a lot of practitioners.

WM It’s interesting…in England a lot of young choreographers, and I’m not just saying they do this for experience, they work in community centres or with young people, and that’s in no way a compromise. It’s actually testing choreographic ideas in a very valid way. And I still do a lot of that work myself—we have a large educational and community program and that’s not to get funding to do other work, it’s actually an opportunity for choreographic investigation. And it may not be—technically—what you are after, but choreographically I’m able to test something new every time. I find the more I do that, the more it’s informed my work.

EB One of the big problems we have here is dancers making the transition to choreography without any real incentive beyond that of creating opportunities to perform. This seems to be due to the small amount of company positions for dancers in relation to the number of dance graduates.

WM I’m sure that’s a problem. In England there are 400 dance companies so a professional dancer has the opportunity to work with a range of very good choreographers, so I guess that’s a big difference. I think it’s a really hard transition and, as a choreographer, you really have to have something to say. For a lot of dancers it’s just the idea of being a choreographer that’s appealing, and that’s not an idea in itself. There has to be a real burning passion to communicate. I do know a lot of dancers who’ve gone through that transition and worked really hard at it and produced not such great work in the beginning, but through real tenacity and work have been able to develop good choreography. But I think dancers can leave companies too early; they think it would be much better to be the figurehead, but it’s a completely different job. A choreographic workshop like this is a great opportunity for young dancers to try it out and get new perspectives and information and openings without exposing themselves to audiences and critics.

EB What was your knowledge of the Australian dance scene before you came over?

WM I didn’t know much—I’d done some work with Company in Space and had really loved that—their use of new technology and development of new software and ideas of presence are really exciting. And my development director, Sophie Hansen, used to live in Melbourne so she gave me a lot of information about the scene here. But we don’t get to see a lot of Australian work in London—the last thing I saw was Meryl Tankard. I think our assumptions are that it’s very American post-moderny, quite traditional in its form. Or we know the real flashy companies like Sydney Dance Company. But it’s been a real eye-opener being here, seeing some of Gideon’s work on video, talking to people and seeing that really innovative things are happening here. The profile isn’t massive but the work is here.

Choreolab 1999, presented by Chunky Move, July 26 – August 6

RealTime issue #34 Dec-Jan 1999 pg. 30

© Erin Brannigan; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

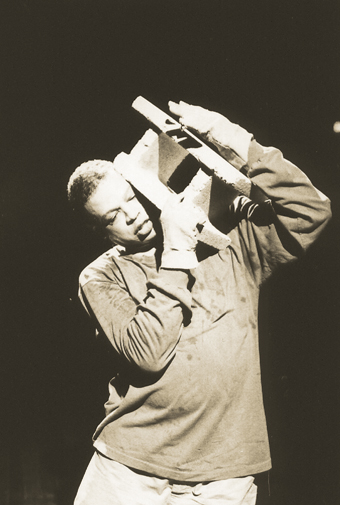

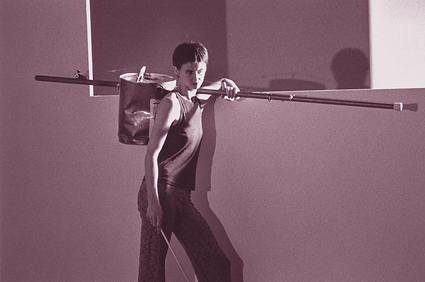

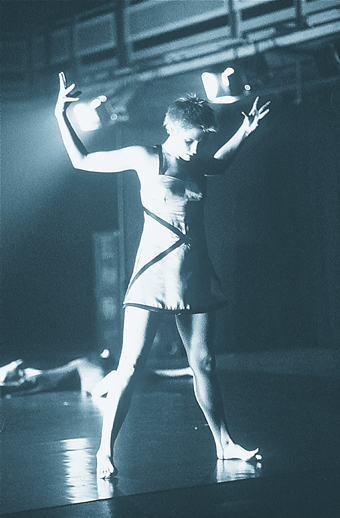

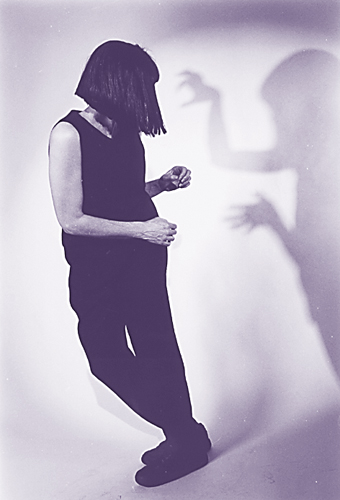

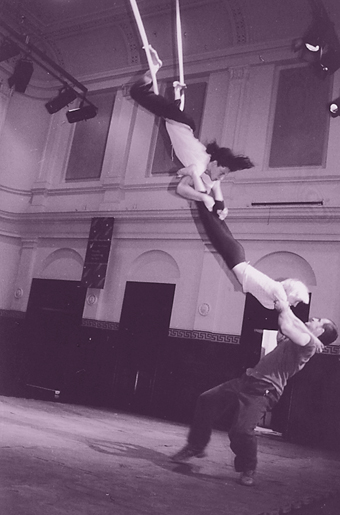

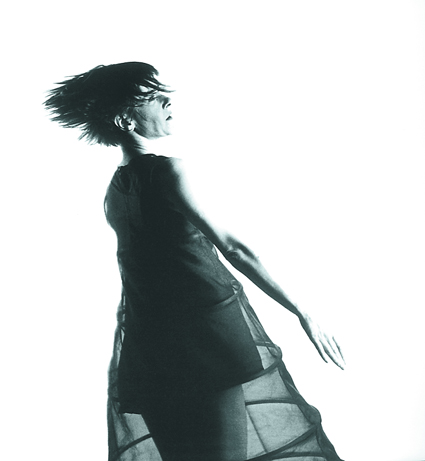

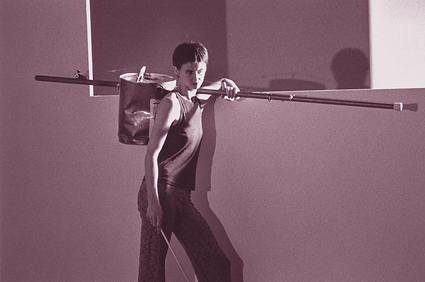

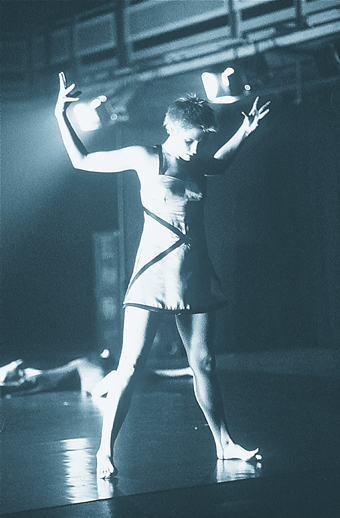

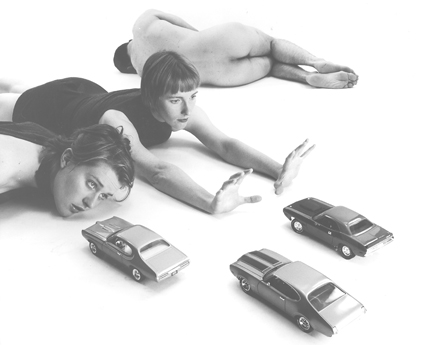

Producciones La Manga, CRANK La Cultura del Safo

Integrated Dance is at last being taken seriously by promoters, reviewers and by the dancers themselves. The form is not a new one but is often perceived as a community sport. I have recently returned from the Art & Soul Festival of Disability Art and Culture in Los Angeles where though viewpoints differed, dance was given high profile in the program of performing, visual and literary arts.

With great reverence to the dance pioneers who paved the way for integrated dance, the international festival did not display an abundance of new work. The most striking new dance came from Producciones La Manga. Their work, CRANK La Cultura del Safo, was described as a “Wheelchair Dancing Investigation Project”. Ten performers from Mexico City with and without wheelchairs powered their teen version La Fura Dels Baus. Delivered with such extraordinary attitude and energy, the work was hard and fast, using effective off-stage dialogue and action. Street fights, rock/paper/scissors images and bullying were running themes for this on-the-pulse representation of Mexican youth street culture.

It is not always the disabled body which makes integrated/disability dance interesting, it is how the performer and/or the choreographer work with that body. The choreography from Gabriela Medina was clever and inclusive and it was often impossible to distinguish who really needed their wheelchairs. They carried each other around the stage and the company’s use of floor rolling and body jumping dramatically demonstrated their strength and endurance. Despite its serious need of a trim, the company performed some of the most abstract and exciting wheelchair dancing I have seen to date.

Artistic Coordinator, Mario Villa, explained that the piece simply came from a workshop project that developed into a full work. The group have been working together and receiving various grants and awards since 1995 and are currently working on a new investigation project. I hope we see them soon in Australia.

CRANK La Cultura del Safo, Producciones La Manga, Art & Soul International Festival of Disability Art and Culture, The Los Angeles Western Bonaventure Hotel, May 28 – June 2 1999. For further info, contact VSA at http://www.vsarts.org/

RealTime issue #34 Dec-Jan 1999 pg. 31

© Kat Worth; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

IGNEOUS, an integrated dance company based in Lismore, recently gave previews of their movement and multimedia performance installations, Manipulations and Hands (works in progress), where the audience were encouraged to move through the space and survey the interaction of drama, dance, video, slides, soundscapes, live music, puppetry and sketching. Directed by Suzon Fuks, choreographed by James Cunningham and created in collaboration with the cast, the works explore the ways we use our hands to express, to threaten, to love and to create. Kath Duncan, star of the documentary My One-Legged Dream Lover, contributed text about hands: “You can’t have a one-armed flower girl. What would people think!” Formed by Cunningham and Fuks 5 years ago, IGNEOUS features adults and children (in the 4 adults there are only 6 functioning arms) and focuses on the interaction of performance and projected image. Possibilities come to life when physical difference and the beauty of awkwardness join forces.

Manipulations & Hands, Northern Rivers Conservatorium, Lismore, October 30-31. For more information, call 02 6682 4015, fax 02 6682 5691

RealTime issue #34 Dec-Jan 1999 pg. 30

© inhouse ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

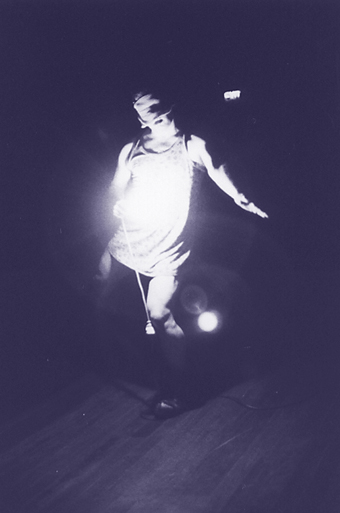

Beautiful People, D-Faces of Youth Arts

The crowd at Whyalla’s Middleback Theatre was buzzing as a warm wash of lights filled the stage and fell on the closed forms of 3 dancers. The heavy bass of a rhythm and blues track vibrated through my ribcage. In a prelude to the main performance of the evening, 4 short dance pieces introduced themes of cultural diversity and turned the audience onto the physical dynamism of D-Faces of Youth Arts, a company integrating performers with and without disabilities. I broke into a sweat just watching the dancers warm up.

D-Faces began their piece with a maze of movement, image, soundscape—sensations of a bustling urban landscape; kids rollerblading, skating, running, playing, traffic blaring. Into this were woven heartfelt narratives of the kind of isolation that sits heavily in your chest and the relief that comes with friendship and acceptance. Schoolyard scenes were re-created, gangs exchanged confidences and angry insults. It is here, within the schoolyard, that young people explore the politics of culture and identity.

Directed by Sasha Zahra, Beautiful People suggested that occupying a polarised position of self-definition is a confined place to be. A warm and wild samba made light of racial debates; in a satire of the mantra of “them” and “us”, D-Faces reminded us that between either end of a social strata lies a dance of engagement and self-definition.

Beautiful People D-Faces of Youth Arts, Middleback Theatre, Whyalla, South Australia, November 6

RealTime issue #34 Dec-Jan 1999 pg. 30

© Anna Hickey; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Prelude: an opening

At the crowded opening of Crime Scene (curators Ross Gibson and Kate Richards, Police and Justice Museum), we move slowly through the key room of the exhibition, curious about the shots of empty streetscapes where murders, rapes and accidents have taken place and been duly documented by police photographers whose constant practice yields a certain eerie artistry. The titles are perfunctory. But there’s still a chill, as if the photographs were records of hauntings—for barely a second your brain involuntarily fills in the fallen bicycle and the body of the 7 year old next to it. Ghosts. Further along the exhibition room, no imagining is required. Or it’s of a different order.

Some of the opening-nighters turn away. Others move in, peering—are we seeing this? A murdered mother and son neatly placed beneath the frame of a bed, posed almost as if in prayer. This is almost too much. How can this be shared with those pressing in around you? You move on. An empty kitchen, mess, a solitary high heeled shoe. Rape scene. It’s a chilling celebration, this opening. A few days later in the Sydney Morning Herald, John McPhee reviewing Crime Scene, worries at what he sees as inadequate notification at the entrance to the exhibition of what it contains (Warning. Some of the images in this exhibition may cause distress.). “No warning can discourage the voyeurs, but what chance is there of a surviving victim or a relative recognising a place that would bring back horrific memories? Do we have the right to use such images to make an exhibition?” (John McPhee, “Still life captures death’s essence”, SMH Nov 24). It’s not inconceivable—most of the photographs are from 1945 -1960. With the review are 2 photographs, one of a badly dented car chassis (Bondi car accident circa 1956), the other, a full size reproduction of a photograph of murdered man in a Balmain living room, 1956, and what looks like blood on the walls. Who might open the Herald and recognise a face, the body, the room…

Crime Scene is fascinating and is about more than its set of carefully selected photographs; it is about crime, about photography, documentation and forensics, and cultural history. Interviews, computer-stored information and on-the-wall documentation open out the exhibition. Nonetheless, the photographs, in their simplicity and their immediacy, are scanned onto your wetware and over the coming days they’re impossible to delete. An uneasy feeling follows you about, like the day after you dream that perhaps you’ve murdered someone, that somehow you’ve been implicated…you are complicit.

Act one: Another opening

As openings go, Dennis Del Favero’s Yugoslavian War Trilogy exhibition at the Australian Centre for Photography last month is a memorable one. Blanche D’Alpuget speaks emotionally about her meeting with a woman who had survived the Bosnian rape camps and how despite her efforts to contain it, the pain of her experience seeped into the detail of her daily life. The speech comes after we’ve viewed the first part of the exhibition, Pietà, in Eamon D’Arcy’s rude structure in St John’s Uniting Church. Inside this room within a room, our perceptions vertiginously up-ended, we watch projections onto a bed on the wall in front of us, and a chair, and a fan, a clock…all white. Tony MacGregor’s soundscore evokes the racking grind of helicopters, surveillance, a sense of urgency, like a song you can’t get out of your head. The images are equally disturbing, especially as their significance unfolds in the narrative loop—a mother tries to trace her murdered son whose body has been used by soldiers for target practice. She wants to bury him. A hospital mends its war victims only to release them to certain death, the murderers await them in the street. Unlike the rest of the trilogy, this footage is raw, the bandages, the blood, the wound, the aerial view of pleasant farms and forests barbarised. It’s good to get out of this sensurround murder scene, though you’ve probably watched it three times before you’ve registered the loop. The nightmare recurs, already.

Outside the room, we’re offered incongruous glasses of champagne. We take them and move through the candle-lit vestry and out into the night where we have the sort of conversations you have at any opening though this time they all begin with D’Alpuget’s speech and how it somehow stilled us. This time there are not too many of us. There’s enough quiet to reflect. Reflection: Pietà is a loaded gun (small dark claustrophobic room, within a church, a vertigo-inducing room, a soundtrack that won’t let you alone, images that are fuzzy, breaking up, but too real). Is someone trying to put the smoking gun in your hand? No. Pietà simply puts you in the picture, or above it; you’re up there, looking down like…God? or the Serbian airforce…?

Act 2: Deeper in

We’re thankful for the time it takes to walk down Oxford Street to the gallery for part 2, Cross Currents. Inside the main gallery of the Australian Centre for Photography our field of vision is filled with huge black and white split-screen images of cities, male and female body parts, landscapes, forests, all stretched across the space, doubled and reversed and Rohrschach Test-like folding in and out of themselves, taking our eyes with them, drawing us in and in.

The disturbing effect of Pietà is at first doubled in Cross Currents by the scale and the device and again, the sound. But this time the view is eye level. We’re on the ground. In a train. In a hotel room. Closer. The black and white photography and the artifice of its showing, however, are a little distancing, this is not as literal as Pietà. The narrative, as you piece it together, seems at first banal. “Cross Currents looks at…(the) aftermath (of the war) through a narrative dealing with the relationship between a young mail-order bride who has fled from Croatia and the Serbian body-guard hired to ‘protect’ her after she is forced into prostitution in Berlin” (Del Favero, CD-ROM booklet). And it’s like a movie, the scale, the black and white evoking an earlier generation of war films; drab landscapes rattles by, soldiers walk ruined streets. But it’s a narrative you piece together and therefore invest in—fleshing out dialogues that speak of emptiness, imagining the relationship between these naked bodies in this neat Berlin hotel room. You watch over and over until it makes some kind of sense. Because you are not given the narrative in a straight line, you feel like an outsider, but out of the banalities you build an enormity. You know what happened, that war, you try to connect it with what you hear and see now…you try to make sense of this aftermath…which never stops.

At home, on the CD-ROM you can worry at it, over and over, discovering new details, new evidence. You start to see the faces of the players, glimpsed in a mirror, or their heads straining back away from their naked bodies. This is a worrying curiosity machine. The devil is in the detail. It takes you in. When you first open it, a widescreen image of a hotel room rotates on the horizontal and your arrow transforms to a viewfinder, on the window, the mirror, the TV and at several points on the bed. You open up slices of narrative voiced over the same imploding doublings you saw in the gallery. You go back to the scenes of the crimes. You know too much, but you never know enough.

Dennis Del Favero tells us later that in the installation of this work at ZKM in Karlsruhe, the lone viewer entered a room with a severely tilted and wedge-shaped floor. Interacting with the viewer’s movements the split-screen video projection beamed onto two intersecting walls of the room—rather than the flat screen at the ACP. The sense of being drawn in, dragged in, implicated, would have been even greater. The triggering of spaces and bodies more alarmingly involuntary.

If Pietà was brutal, and by now it feels like it was, Cross Currents is so darkly melancholic you could drown in it—the size of the images, the depth of the sound, the forever folding images, like currents cutting across each other into nothing (but an invisible force, yes, a black hole). There’s sadness in the telling made moreso by the wavering drone underscoring the dialogue, broken only by a sudden orgasmic groan, an inexplicable burst of children’s play, a woman’s cry, scary male laughter breaking into the room. Of course, when you open the door, the window, the TV, the bed…sound rushes in, the wailing of a high speed train or, quiet again, the simple untheatrical dialogue of the ‘couple’, the clink of glass, ice…The limited lexicon of sounds locks you in.

Act 3: Too deep

Motel Vilina Vlas is the third part of the trilogy and installed in the smallest room of the gallery. Another small room. Again, the frightening effect is doubled in the duplication of means. An horrific story unfolds in a blameless text and a set of cibachrome photographs. A woman survives the atrocities of the rape camps and a soldier who refused to take part is in turn murdered by his own family. After everything else, this, the most detached of tellings has the most murderous effect. It is silent.

Act 4: Penetration

The specificity of the stories, the ever increasing detail you find in the images, the links you make between these and what you already know about the Bosnian war and the eternal question, ‘how could they do it?’ (not quite yet ‘how could we?’—that’s something to wake up to at 3 in the morning), this is the work of the Trilogy. You are implicated by being put in the story/experience, by being told it (that can be enough–D’Alpuget’s story or Motel Vilina Vlas), or by allowing it in—eye, ear, the stomach it hits—and out again—I will tell you what I saw, heard, felt…The Yugoslav War Trilogy is penetrating. Nikos Papastergiadis declares in the essay accompanying the CD-ROM that the works are “more like meditations on the nightmares of modernity rather than they are declarations of abuse and injustice in a specific place.” It’s always good to claim some universality for a work of art, it’s a kind of relief and an elevation of the work as art, and they aren’t accusatory, but the devil is in the detail, and Del Favero and collaborators’ arsenal of devices are too potent, too penetrating, too specific, to induce meditation. Fear comes first, and disbelief, and anxiety that stays.

Act 5: The interpretation of dreams

“Although passed over in the general coverage of the hostilities, these events involving genocide, rape camps and sexual slavery are in many ways defining symbols of a war which consciously used sex as a cultural and military weapon.”

Denis Del Favero, The Yugoslavian War Trilogy CD-ROM booklet

This is a visceral work. It gets inside you and it’s hard to get it out, as if it’s attached itself to your organs. And to your brain—it’s psychological, not in the sense that characters are created with depth or that a narrator explains himself, but in the sense that it does its work on you, becomes part of your psychology. Knowing this of Del Favero’s work, we were anxious about even going to the opening. And in Cross Currents it’s psychoanalytic, as a kind of visual poetic, intended or not, the centre of the screen (where everything doubled is sucked in or pushed out) becoming an engulfing (war) wound, where tangled trees resolve into sudden pudenda, limbs and armpit hair condense into a groin, two breasts merge into one primal one, 2 brows (are they?) fuse into something anal, an eye is fish-eye lensed and doubled into a monstrous animal, that glowers at your voyeurism, but, look, there are tears waiting to fall…every orifice is open, forced or waiting.

Like a dream Cross Currents falls apart, starts up again, is remembered in fragments, is observed, is participated in, is triggered. Like a neurosis, that most waking of dreams, it is something to go over and over, opening the CD-ROM, entering the hotel room, clicking on the door, the window, the TV, the bed, the bed, the bed…

Meditation’s not the right word, the works are too urgent for that, too keen for you to feel their pain, too eager to implicate, to place you at this crime scene and to get you coming back and back…though not quite to pin the crime on you. They are too often noisy, too sudden for reflection. But melancholy, there’s something in that, later on, on the way home, the next day, a week later, a feeling, rather than an idea…the sad narrative of Cross Currents, the sense of aftermath, of unresolvable loss, the nostalgic wartime black and white, that drone, bodies folding into themselves, the sound of children’s play. It was once hoped that the evils of the first half of the century had been conquered, but they have come back and back, slaughters and genocides, astonishing inequities. Our anger and melancholy sit side by side, just barring the way to the black hole.

Dennis Del Favero, Yugoslavian War Trilogy, sound design Tony MacGregor, produced at tthe Institute for Visual Media (ZKM), Karlsruhe, Germany, 1999. Australian Centre for Photography October 1 – 24

Cross Currents, Centre for Contemporary Photography, Melbourne, August 27 – September 25

Crime Scene, Police and Justice Museum, Sydney, November 13 1999 – October 2 2000

RealTime issue #34 Dec-Jan 1999 pg. 32

© Keith Gallasch & Virginia Baxter; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Driving through the Moorooka Magic Mile of Motors on our way to Global Arts Link at Ipswich for the launch of the Double Happiness 2_nations website, Beth Jackson (Director, Griffith Artworks) is telling us how academic colleagues were surprised to see her in the Queen Street Mall on Thursday night spruiking with Festival Director Kim Machan and Sein Chew (Macromedia Asia-Pacific), throwing T-shirts to the crowd and cracking jokes to officially open MAAP99. What did one science fiction writer say to the other? The future’s not what it used to be. Real or virtual, places do things to you.

Just last week in Sydney I saw Komninos at the Poets Festival calling in the hollows of the Balmain Town Hall for some new discussions of place that have nothing to do with the well-turned topic of landscape—places beyond addresses, places of the mind, of memory, states of being. Komninos calls himself a cyberpoet these days but for the opening of MAAP99, he’s back on the street and literally a driven man, his programmed video poetry threatening sometimes to run him down. Images from his family album are montaged, magnified and left open to the brisk Friday night Mall traffic. Intimate word pictures of a childhood in Richmond and his grandmother’s undies, cosier online, here die of exposure. More at home is his shout to exorcise the 60s from the collective imagination, “The Beatles is dead! DEAD”!

As Komninos calls up the Richmond streetscape, coloured words duck and weave across the screen—“Cars CAAAAAAAARS.” Gail Priest thinks Sesame Street and Maryanne Lynch wonders if he knows that until the 60s a tramline ran through the Queen Street Mall and, indeed, through the very spot on which he’s standing. Me, I’m searching for a place in my memory bank for “international virtual pop star” Diki conceived in Japan, now living in Korea. Gail says “Imagine if you could do anything you wanted with technology and your fantasy was that!” A pale, gawky teenage girl in big black bloomers dancing on lolly legs perilously close to the edge of some pier. The clip is intercut with vision of the remarkably Diki-like male (?) artist weaving his spell in some late-night media lab. Weird city.

At the Valley Corner Restaurant the new tastes good—shallot pancakes and deep-fried broccoli leaves with shredded sea scallops. On one side of the table a couple of web designers on laptops point with chopsticks at their wares. Artist Richard Grayson’s projections have tonight failed to materialise on the walls of the Performing Arts Complex. He whispers to us across the crispy flounder what the building should be saying to drivers crossing the Victoria Bridge. It sounds like “Slowly you are coming closer to the speed of light.”

For now, websites are still launched by a gathering of people in one place. At Global Arts Link in Ipswich for the opening of Double Happiness 2_nations we are doubly welcomed by Aboriginal dancers in body paint playing with fire and pale Chinese dancers in pink pantsuits waving fans. The mayor of Ipswich speaks warmly of technology while the head of the Australia-China Friendship Society gestures in the direction of the IMAC console and declares the site “launched or …open”. Director Louise Denoon shows us through the space opened in May this year for a sneak preview of The Road to Cherbourg, a remarkable exhibition of paintings by Queenslander Vincent Serico about mission life and life beyond the mission. Global’s vision (“Linking people to place through the visual arts, social history and new technology”) maps Global as a kind of future place and again, not the future we expected. The heritage Ipswich Town Hall provides the framework for the multiple spaces within it. This is a comfortable place, its spaces adaptable. Near Vincent Serico’s painted didgeridoos, Louise points to a hole in the floor and the space below it to take cabling as required. The ground floor interactives offer individual spoken memories of this place—“Talk the talk, not the technology” says curator Frank Chalmers. Upstairs a subtantial space is allocated for children to paint with computers and draw with pencils.

After a weekend of screenings, our bodies spinning with visions, we dive back into the Valley. Sunday night at the Artists Club@The Zoo Ed Kuepper unleashes a mean version of “Fever” and is joined for “The Way I Make You Feel” by Jimmy Little who these days has moved from “Royal Telephone” to “Quasimodo’s Dream.” For his encore, “Cottonfields”, a didgeridoo player springs out of nowhere and plays up a storm.

MAAP99 may be a festival to experience online but there’s still a lot to be said for being here on the ground

MAAP 99 Launch, Upper Stage, Queen Street Mall, Brisbane, September 3; Official Opening Double Happiness 2_nations Global Arts Link, Ipswich, September 4; Artists Club @ The Zoo, Sunday September 5

RealTime issue #34 Dec-Jan 1999 pg.

© Virginia Baxter; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

CONTACT Unstable Fields of Power is a brilliant piece of cross-cultural melange. Four artists from Bandung (Indonesia) and four from Perth collaborated on a project that is both an experimental artists’ exchange, conducted online, and an exhibition of new media works. Rick Vermey sets the tone and scares luddite internet users with laptop meltdown as his screen interface goes crazy.

The Indonesian artists are really strong on image, composition and colour in more traditional works adapted for exhibition on the web. Their artworks are bulging with meaning and narrative and are replete with theatrical grotesquerie that is finding explicitly modern forms. Rikrik Kusmara presents four compelling wooden sculptural installations that have a forceful sense of space and colour. Diyato’s dramatic works are visually amazing—although they could make better viewing in the canvas. The web hosts these artists’ usual projects and biogs, but where are their online works?

Now if you are not a net-fool like me you will get through to the online works straight away rather than thinking that the Indonesians were given a raw deal. When you do, you will find that there are some intriguing experimentations that betray a wicked sense of humour. Diyato’s little film is an allegoric transformation by fire. While W. Christiawan gets right into funny animal noises, his “postcards from the edge” and “throwing hopes” are intense evocations of how contemporary Indonesian political life pervades the everyday. These are strong, simple applications of the web to represent personal experiences.

Krisna Murti appropriates and responds to the new social stimuli in a more engaged way. She says that “in the last one decade, Indonesian TV’s commercial advertisements have radically pushed a social change, breaking the ethic value.” The lack of warning and the pervasiveness of tampons ads on Indonesia TV prompted Murti to respond with a provocative anti-ad where she re-interprets a tampon commercial in order to show how the tampon can be used for other domestic applications. She also presents an interactive with useful instructions for transforming the tampon into a teabag or a cold compress for use by men to cool their brains.

In fact there was a fair bit of humour in this exhibition, particularly from the female artists. This seems to be something of a prevailing trend in Perth. Amanda Alderson presents a remarkably accurate anthropological study in game format of going out on a Saturday night south of the river in Perth with the scuzzy males that inhabit the region. This interactive and the associated artwork spill out of the ubiquitous and terrifying symbols of suburbia—the big green rubbish bins.

The adventure starts from the invite on the mobile on Saturday afternoon and goes through all the painful rites of choice from brand of bloke to drinks, pick-up lines, cars, clothes, choice phrases and puke places that can be had on the night. At every point there is a choice but the range of choices is hilariously dispiriting. The selection of guys to go out with is big but believe me, after this night, you will never go out with that type again. It is a cringingly correct representation of the Saturday night party scene with superb sound bytes to accompany the decisions that you make. They capture all the proudly nasal mono-syllabic beauty of the Aussie bloke. I went through the ordeal a couple of times to try my luck with different guys. This is potently precise contemporary anthropology (she must be an insider) sprinkled with colourful linguistic and cultural particularities of Perthlings. It’s a classic! I was wondering what the Indonesians made of this piece.