Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

Looking at developments at the One Extra Dance Company and the emergence of The Choreographic Centre in Canberra, Eleanor Brickhill interviews the new non-choreographing directors and queries each company’s new structure.

Comparison of comments in the Dance Committee Assessment Reports on funding and policy in the last few years reveals that in 1994, particular interest was given to “developments involving dance and other media”; in 1995, the aim was “to maintain its commitment to independent artists and a range of work practices”; in 1996, the newly named Fund focused on “innovation, artistic vision, and a diversity of cultures and artistic practices, more than on the maintenance of particular structures or forms”.

Symptomatic of changing emphases, small company artistic directors being compelled to reconsider basic organisational structures, may well have felt unable to continue working without support for what they believed essential to maintaining artistic standards. The resulting resignations (for instance, Sue Healey, Graeme Watson, Julie-Anne Long, Chrissie Parrott, Cheryl Stock, Jenny Kinder) seemed to demonstrate extreme protest.

No doubt company boards began tearing their hair trying to construct new answers to the small company ‘problem’, of late perceived as economically non-viable, not pulling in big enough audiences to warrant maintenance of full-time financial support or to attract sufficient sponsorship. Janet Robertson, the new executive producer of One Extra Dance Company, acknowledges that for the next two years at least, there is a bottom line which requires an increase in audiences if that company is to continue to exist at all.

Meanwhile the boards of both Dance Works in Melbourne and One Extra remain committed to a ‘company’ structure, although having an artistic director who’s committed to creating their own work is the choice only of Dance Works.

Both Janet Robertson and Mark Gordon (director of TCC) are deeply aware of the histories of the institutions into which they are entering, wanting to assure people that their new enterprises stand on the shoulders of the old. Both are also aware of the streams of opposition to the loss of existing small company structures within the dance community, and while they have been profoundly concerned about not dismantling the “good bits”, what they are actually building continues to be debated.

Can their assurances assuage fears that losing artistic directors will mean a terminal loss in the development of dance as an independent art form; that the potential depths for dance innovation and development will be confined to the role of theatrical adjunct? Might not the means of developing independent dance aesthetics be simply negated in a drive towards a different set of performative notions, in which language based ideas set the ground rules?

What does a choreographer as artistic director do? It sounds bland to say one loses vital links with a unique body of work once a preferred means of support disappears. But at best, dance artists as collaborators share a deep physical relationship, a profound personal culture, an ethical, even spiritual stance on their bodies, as the basis of their aesthetics, which flourishes in that hothouse. Dancers within this culture literally embody work, and copies made outside that culture are to its detriment. Development of that culture needs more intense hands-on effort than is ever available in a stop/start environment such as freelancing requires. Time is required not so much to ‘make steps’ but to enter that intimacy.

Janet Robertson, executive producer, One Extra Dance Company

Janet Robertson has modelled her role of executive producer more on film tradition, as someone who puts people together, listens to ideas, responds to them, negotiates, and also has a very strong creative role. For her, while the clarity of her vision needs to be maintained, holding fast to specific ideas can muddy the artistic waters. As she understands it, “executive producer” is not just a fancy name for an artistic director, a person single-minded in their commitment to making their own steps, but is someone who makes decisions about what is seen.

Janet spoke about an evident lack of ‘performative notions’ expressed within dance works, separate from the technique, about a need for getting past the dance ‘show’. Her job as executive producer is to demand that a choreographer’s ideas become cohesive, and her talent as company dramaturg, in which capacity she will work on the floor with choreographers, is to be able to get choreographers and dancers to ask themselves just what it is they are doing.

Way back in 1960, Susan Sontag said, “The best criticism dissolves considerations of content into those of form”. Remember Balanchine’s maddening ideas which insist that “the movement is the meaning”. If these ideas still hold true, it is by means of the movement itself, the physical ideas that a dance conveys, that some “secret truth” (Acocella, 1990) of a dance is found. Separating the content of a dance from something called “technique” seems to me highly problematic. If a dance work suffers from a lack of performative skill, perhaps the lack is the technique, not separate from it. Without relevant things to say, technique can make dancing grossly inappropriate and banal, and needs to be dealt with head on, rather than being treated as separate from notions of ‘performance’.

Another perceived problem is that within the current economic climate, dancers and choreographers are forced to work independently, required to continue to produce new work constantly in six-week rehearsal blocks. Artistic directors of a company develop a body of work, perhaps a repertoire. Independents are forced to throw out work and be constantly making new material, rather than redeveloping it. Janet’s concern is with the difficulty of questioning one’s artistic motives when box office is always of prime consideration.

The idea that independent artists are people who throw out their work is problematic too, and an important distinction made between freelance and independent artists still seems valid. Capable of making work in almost any structure, freelance artists tend to work within a kind of generic aesthetic. But independence inherently involves an individual artistic need to work outside of established artistic structures, and doesn’t usually centre on financial necessity. Ideally, evolving one’s own structure in which to work seems a logical and necessary career move for independent choreographers.

The legacy of Kai Tai Chan’s One Extra, working as a huge melting pot for ideas, where people could come and work, while still responding to his central vision, provides an important basis for the new company. There needs to be a core aim to produce work with a particular kind of production value, a ‘house style’, and independents will be asked to respond to that vision when producing work for One Extra. Meanwhile, there is potential for the natural development of teams over time, or an artistic director to take over, to redevelop and reshape the company vision.

The first aspect of the company program for 1997 is the development of relationships with an audience via three seasons of work by proven and established choreographers. Sue Healey has been invited to re-develop an older work, to take the opportunity to have it really critically pulled apart and re-examined. Importantly, an ongoing two-year commitment to any commissioned program provides the means by which independent artists need no longer throw away work just to maintain box office success.

The second program, a double bill with Lucy Guerin and Garry Stewart, with their vastly different profiles, may invite complaints of eclecticism, and begs questions about the constituents of identity and ‘house style’. Neither a dancer nor choreographer on the floor “making steps”, Janet is still a practicing artist, and remains committed to the idea that a cohesive philosophical base forms a strong company identity.

An affiliate artists program starts in January, and the six artists invited to participate include choreographers, designers, dancers, musicians and technicians. There is no fixed ensemble, but several dancers have been invited to become affiliate artists. While entirely free to choose their preferred dancers, choreographers will be encouraged to consider working with the affiliate artists. One Extra will provide a place to discuss work, office facilities, rehearsal and forum space. To a certain extent the work evolving under this scheme will be motivated by the artists themselves, and is not expected to be produced within the company context or vision, although they will receive acknowledgment as working artists in all One Extra publicity.

A third aspect of the company structure concerns creative development through a mentor program. One Extra hopes to provide a strong context in which established artists might work with dancers of their choice, simply exploring their working processes. With no performance outcome necessarily expected, a serious kind of play becomes much more central than usual.

Fourthly, direct educational and community activity will further promote the company’s ongoing relationship with the University of Western Sydney, Nepean, by setting up performance workshops for people whose interest is in physical performance, but who might want to explore text based material.

Mark Gordon, director, The Choreographic Centre

The Choreographic Centre is the most recent incarnation in organising the development of professional dance practice in Canberra, and like One Extra, its history contains the seeds of this current manifestation. By almost a series of accidents Don Asker took up an ANU fellowship in 1980, resulting in the formation of Human Veins Dance Company, and it is important for Mark Gordon, as the new director, that this history is known. Between the old and the new lies Meryl Tankard’s Dance Company, and more recently Sue Healey’s Vis-a-Vis, but the board itself and its long-term commitment to professional dance practice in the ACT, has remained fairly stable. The studios too, in Gorman House, are the same ones that Don Asker used, but now, 16 years later, that whole complex is a rich, busy environment.

The board’s response to Sue Healey’s resignation was to engage widely in consultation with local practising dance artists, arts organisations, the ACT Cultural Development Unit and the Australia Council, as to appropriate action, and the notion of a centre for choreographic research and development emerged. The idea of that first fellowship, along with residency opportunities, became an important part of this vision. But the crucial aspect is that of mentorship, where a variety of experienced artists are available to work in creative partnership with a choreographer, to solve problems, to talk through ideas about what is or is not happening within the process of exploration.

Choreographic partnership shapes Mark Gordon’s role as a director whose talents lie in nurturing new ideas, bringing out the best in people. His role is not curatorial in the sense that artists are directly promoted. But the protection of archives, the previous companies’ histories, and continuing documentation of the life of the Centre, what happens, what succeeds and what doesn’t, carries an important curatorial obligation.

The Armidale Conferences of the 1960s remain for many Australian artists a high point in their creative lives, having provided a nurturing and empowering environment, where no special demands for ‘success’ and no sense of value judgement impinged on work done. The Centre’s patron, Shirley McKechnie described such an environment as a creative broth. This idea has provided a formative model for TCC, and one measure of its success will be whether or not choreographers are attracted to Gorman House as a place for exploration.

Fellowships are variously budgeted between $40,000 and $50,000. But needs may vary tremendously and structuring can be as flexible as imagination and practicality allow. Artists are invited to make proposals for the fellowship program, rather than applications, so that the criteria for success is more about project feasibility than popular appeal.

The fellowships essentially buy time, and like One Extra, the Centre is working towards freeing choreographers from the misery of the six weeks production schedule. Funnily enough, unlike Janet Robertson, Mark describes it as a luxury and a freedom for choreographers to discard work. But then the issue is not really whether a simple move needs to be discarded or retained, but where the actual dance work lies. Moving is never simple, being fraught with meaning, and it is deciphering the many guises of human embodied meaning which really provides the work.

Fellowships are targeted at ‘emerging’ choreographers, not necessarily the young. Essentially they can provide special opportunities for people with vision and potential, but estimating potential is difficult. Submissions therefore need to include references attesting to the artist’s capacity to use the experience to best advantage.

Crucial to the 1997 TCC structure is the advisory panel, and a glance at the personnel (Don Asker, Nanette Hassall, Jennifer Barry Knox, Wesley Enoch, Annie Greig, Garry Lester, Sue Street and Graeme Watson) suggests a wide-ranging understanding of dance making and arts practice will be brought to bear on the ranking of submissions for the three fellowships envisaged for 1997.

The residency program, with a lighter financial commitment, offers access to the Centre’s facilities and resources for choreographers to develop work. A highly flexible program allows an almost infinite range of innovative proposals. Matters of duration, financial assistance and personnel are discussed within the partnership, with advice from the advisory panel.

The flipside to both fellowship and residency programs is public outcome. With exploration and research as the primary focus, outcome will be measured not by performance, but a different kind of public access. The local community needs to feel a benefit from the Centre, and opposition can arise when choreographers makes the space so private that no-one can enter, either metaphorically or literally. Fellowship recipients will need to integrate some degree of public access into their schedule, although there are no rules about what form this might take.

By way of sharing ideas and to gently open up dialogue, Mark Gordon envisages choreographic luncheons, where local people might meet choreographers, perhaps see videos, ask questions, to develop perspectives on dance practice. He also wants to set up a writers’ group whose charter is to develop writing about dance outside of criticism. If genuine dialogue between writer and choreographer is just an ideal, the results may still benefit archival documentation.

* * * *

These activities seem so closely interwoven as to create of a kind of performance ‘safety net’, and engender confidence in those afraid of falling. But for others whose artistic footing is surer, and who crave danger and isolation, a source of joy may seem stopped. Both Mark and Janet’s undoubted strengths will be welcome and liberating for some, performers and audience alike, even if the singleminded and uncompromising among us find such stimulation more of an irritant.

In many ways, Mark Gordon and Janet Robertson’s visions dove-tail well. Their enterprises seem built for survival, and between the two of them, they may flourish.

RealTime issue #16 Dec-Jan 1996 pg. 8

© Eleanor Brickhill; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

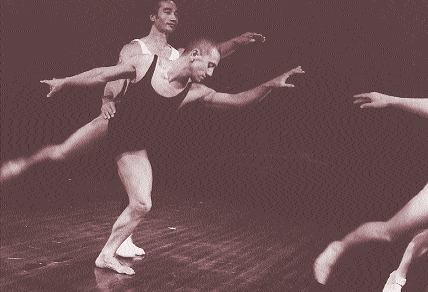

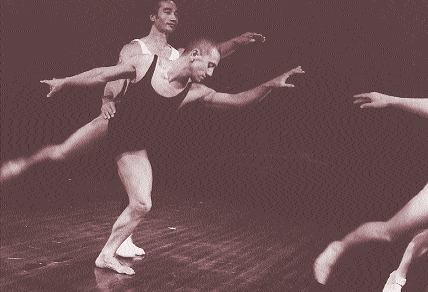

Black Grace

photo Heidrun Löhr

Black Grace

In describing what a dance might mean, people often refer to frames of reference, something which might indicate how to look at a dance so that it makes sense. These days, dancing is also about frames, demonstrating shifting perspectives, requiring the viewer to slide around multiple trains of thought as if over teflon.

In Face Value, we see Kate Champion through windows in a monstrous facade, tiny framed views of her various relationships with the world and more particularly with men, over the years. Another world far behind sends galvanic warnings of storm and stress. Lights flare and briefly illuminate a profound and scary desolation, a vast, empty space with rotting beams, about to collapse. Sometimes we also notice images that seem transparent in their invitation to see past her daily skin. Soon, however, we become aware that these images of her as uncomfortable yet willing model, anorexic, a woman slowly being crushed as she sleeps, are opaque. The blinds are down.

Frames also reveal secret non sequiturs. Kate Champion tells us about the profound relationship between a person’s social skin and their inner life, assured that it is remarkable, a source of both strength and destruction. But the secret in Face Value is that we never get to see the hidden passage from one to the other. No artist’s insight illuminates the way, and we are left stranded in unwilling collusion and vapid inference. Kate’s gorgeous 34-year-old ‘facade’, in several costumes, remains the primary source of insight, and any talk we hear about menopausal decline and resurrection seems frankly spurious.

What did the six separate Bodies programs (Newtown Theatre) show us? Simply that the frames of reference for most young dispossessed dancers are so tight-arsed as to be suffocating. We are asked to find sustenance in a narrow and ill-fitting series of classroom steps, which for the most part, arising from ancient techniques engendered in the 70s, have lost any power they might once have had.

Dean Walsh, Hardware Pt I

photo Heidrun Löhr

Dean Walsh, Hardware Pt I

But here’s an interesting example of censorship! Dean Walsh with his riveting comments on male physicality, in Hardware Part II and Testos/Terrain, was obliged by the management to warn the audience to leave if they might be offended by his “male nudity” which included the riotous sight of his anus. It’s a pity we weren’t warned about another piece, Duet 4/4, in which two pre-pubescent girls were obliged to adopt sequences of ‘pout, waggle and smile’ as their preferred if naive style, closely accompanied by two older girls, no doubt demonstrating the condition they might be lucky enough to grow up into, if only they can smile for long enough. The idea of child pornography sprang immediately to mind.

But Dean Walsh’s Testos/Terrain is not about homosexuality or even being male, but about being human. His insights seems hard-won, and profoundly embodied. His ghastly singleted ‘male’, who at first seems to have forgotten his opposable thumb, eventually shows us a place where instinct, animal curiosity, intelligence, and physical nature meet, way below daily manifestations of gender. At this junction, there is a well of polymorphous sensibility. For building a human home of whatever kind, boys’ toys may just as well be lipstick here; the creative playing is the same, and it’s only the tools of implementation that are different.

Jeff Stein’s performance in Lard, at October’s Eventspace at The Performance Space, showed another kind of physicality altogether. Unlike Dean, his is not defined by muscular and emotional depth, but by skittering skin-deep neural patterns, visible thoughts which tie up his frame in a kind of dance of simultaneous and conflicting directions. His being is expressed as if merely a series of whims, a collection of certainly more than two minds; he spars with spectres; he is ingenuous, just there, and sometimes he seems afraid of just taking up space.

Black Grace

photo Heidrun Löhr

Black Grace

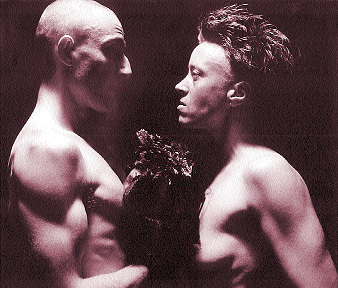

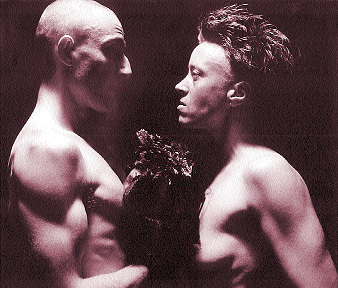

Watching Black Grace, an all-male New Zealand based group, as part of Pacific Wave at The Performance Space, was an unexpectedly moving experience. New company, first work, raging success: a terribly hard act to follow. Ex-football players, professional drag queens, nine dancers highly trained in western techniques among more traditional ones, brought a sophisticated humour, and a mix of lissom and weighty vitality to Neil Ieremia’s personal statement. What to say about wanting to be a dancer (“Not a ‘dancer’, a dancer!”) in a virulently hetero black Maori culture? Where do dreams of wanting to be weightless go? Is being a florist really unthinkably weird? The threads of these and other hard questions are unravelled as Black Grace’s stories of personal experience are retold.

If their most conspicuous physicality has grown out of contemporary European dance lineage (Douglas Wright via DV8 and Batsheva perhaps), it frames glimpses of black traditions: urban rap and Maori haka for instance. Black Grace itself, in a literal sense, is about journeys across the world’s dance floors, and about risking familial and peer group isolation in the attempt to comfortably embody simultaneous and divergent cultures.

There is very little gratuitous material in the choreography of Black Grace, not many extraneous gestures. It is straightforward and often poignant. And there is real joy in the visceral charge, the resilience of unabated competence, the smudged unconfined edges of movement made emotionally resonant, the streams of sensuality, and the heavy, moist thwack of muscle and sinew thankfully audible when the other music stops.

–

Face Value, Kate Champion, The Performance Space November 8-12; Bodies, The Newtown Theatre October 23-November 10; Eventspace, The Performance Space, October 30; Black Grace, The Performance Space, November 15.

RealTime issue #16 Dec-Jan 1996 pg. 9

© Eleanor Brickhill; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

The real value of this symposium lay in its intersection between potentially conflicting fields—the grass-roots methodologies inherent in community arts, and the still-rarefied strata of digital technologies. As such, the symposium was aimed more towards the community end of practice, a welcome space in which to discuss the implications of emerging technology without the tech-heads or the incomprehensible minutiae required to explain the operations of digital media. Credit goes to symposium artistic director Lylie Fisher for placing content and means on the agenda, firmly ahead of form, rounded out by a comprehensive series of hands-on workshops and demonstrations held each afternoon. It’s perfectly fine to explore what we can do with this technology, but it is imperative to discuss why we would want to do it at all, pushing debate beyond the Mt Everest (because it’s there) syndrome.

As it turns out, the community arts is a contentious arena in which to stage this debate. Its more traditional supporters and practitioners view the technology with suspicion, as exemplifying the alienation inherent in Western industrialism—the enemy of the people. If it is that, it should be cast in Ibsen’s appropriation of the term: something crucial is happening and to turn our backs to it is at our own peril. Key-note speaker Stephen Alexandra hinted precisely at this, that to avoid this technological revolution is to cast the community arts as envisioned in the 70s even further into ghettoisation and marginalistion. But he also stressed some of the peculiarities and contradictions inherent in the structure of new beasts like the internet and other digital media. On one level we find the power struggles of multinationals seeking their stake in information technologies, dynamic battles which will restructure our concepts of national autonomy, cultural boundaries, commercial and civil infrastructures. On another, there exists a digital community which is best described as grass-roots with a virtually (pun intended) unfettered exchange of information and ideas, including political organisation and protest. As a mass-medium, the net circumvents other ideologically determined media, as described in Noam Chomsky’s Manufacturing Consent. Quite to the contrary, the net provides the perfect opportunity for Chomsky’s celebration of counterculture, whether it be environmental activism or gay lobbying (as discussed in detail in Michelangelo Signorile’s Queer in America: Sex, the Media and the Closets of Power, Abacus 1993). This is because the plethora of content on the web is so diverse that it mimics a genuine anarchy. Later speakers would throw cold water on certain cherished concepts of web-utopia. But in the meantime, we can say that while corporate battles are waged, individual expression runs riot, as any web-surfer would be aware.

Speakers who followed over the next few days (many familiar to readers of these pages) only emphasised this point: Francesca da Rimini speaking about the work of VNS Matrix, Zane Trow on his role as Artistic Director of the Next Wave Festival, Brett Spilsbury on Australian Network for Art and Technology’s seeding work for art in the digital arena, and Michael Doneman’s run-through of a website for Brisbane’s youth arts organisation, Contact Inc. I was delighted by some of the contrasting approaches given expression over the three days.

da Rimini, for example, emphasised the non-technological approach of VNS Matrix’s efforts. Working only on a need to know basis, and drawing on expert help when required, emphasis is placed firmly on discursive strategies fluidly aimed at subverting a patriarchal unconsciousness most popularly summarised as ‘boys and their toys’. Yet implicit in VNS Matrix’s approach is a growing awareness and sophistication: once you start playing with this stuff, you start getting good at it. Still, VNS Matrix have succeeded by deciding on a focus, their pro-libertarian feminism is refreshing, the final effect delightfully fearless. In contrast at least to VNS Matrix’s stated aims, Zane Trow emphasised the skill of the artist who uses the computer as a virtuoso instrument. He presented a devastatingly brief manifesto of such wit and truth that its more unpalatable side was greeted with guffaws of recognition, especially “our art is so radical it is sponsored by the government”. Perhaps because his background is in sound and composition/performance, one of the first arts practices to embrace digital technology, his attitude was refreshingly down to earth. The computer is just a tool. Or, again recalling Chomsky, a reminder that if access to digital information could really change things, the Pentagon wouldn’t let us have it. As it is, cyberculture is best characterised as ‘adolescent’, not democratic. But most importantly, it was stressed that community arts in the digital age would never be about ‘decoration’, which has characterised Western art since the baroque met bourgeois ideology. That in itself is a breakthrough, making digital art about ‘things’ (if not objects), and implying links between the virtual world and the material one of bodies, communities and power.

The symposium had the excellent sense to address exactly these issues by choosing artists working in both multicultural and indigenous contexts such as the Milanese Ermanno “Gommo” Guarneri who gave an account of disenfranchised Italian youth who have moved into cyberspace to conduct community events. Last month, the old News building on Adelaide’s North Terrace, the origin of Rupert Murdoch’s media empire, caught fire—no doubt through the activities of homeless street kids. Imagine instead that it is filled with computers, begged and borrowed, hooked into the web as an integral part of its fabric and giving voice to an anarchist youth who find this technology as familiar to them as phones. This might scare people, but frankly, Gommo’s account of such events in Italy looked a lot like fun. In Australia however, it won’t be street kids working this stuff, but the (hopefully not) well heeled children of the bourgeoisie. It still raises the question of community access which is where Gary Brennan’s somewhat dry address to the symposium belied the importance of what he had to say. Gary’s consultancies with both the Australia Council and the Australian Film Commission have identified the means for providing access, basing skunkworks in the existing Screen Cultural resource organisations such as Metro, Open Channel, the Media Resource Centre and FTI in Perth. This deserves a report to itself.

United Trades and Labour Council of Australia Symposium: Community Cultural Development and Multimedia, Mercury Cinema, Adelaide, September 24-26.

RealTime issue #16 Dec-Jan 1996 pg. 24

© John McConchie; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Daniela Alia Plewe

In assessing the recent International Symposium on Electronic Art (ISEA96) [http://www.isea96.nl/index.html – expired] and related events held in Europe this September, I have decided to focus on the aspects of the fora which related to the internet. This may seem like an unlikely decision, as these events are specifically about the ‘fleshmeet’: seeing new installation based works, listening to and talking about issues facing artists working in electronic media. However, the mad rush to go on-line has infected so many aspects of art and cultural practice that it seems pertinent to have a look at what artists are doing in this area and to focus on the many disparate critical discourses currently in circulation. Furthermore, in reflecting on the events I attended, I have found myself continuously drawn back to the internet, finding that this manifestation of the ‘real life’ events finds resonance in the on-line after-effects.

In an article on the Nettime list [http://mediafilter.org/ZK/Conf/ZKindex.html – expired] the Critical Art Ensemble has written, “The need for net criticism is a matter of overwhelming urgency. While a number of critics have approached the new world of computerised communications with a healthy amount of scepticism, their message has been lost in the noise and spectacle of the corporate hype—the unstoppable tidal wave of seduction has enveloped so many in its dynamic utopian beauty that little time for careful reflection is left”. I would suggest that the amount of critical work being done on-line is not so much the issue, as the poor resources available in this area for presenting ideas and furthering discussion in a coherent manner without centralising any kind of power base.

Prior to attending ISEA this year, I decided to check out the 15-year-old European Media Art Festival (EMAF) [http://www.emaf.de/]. The festival, which like many of its genre started life looking at experimental film and video art, this year extended itself to include a range of video, film, performance, exhibition and on-line components. Almost as compelling as the site-specific works presented was the opportunity to log on and check out the cyber dimension. I travelled across the world to meet people and see art, yet found as much satisfaction in finding the time to log on to the internet and check out what is going on in the same ‘cyberspace’ I can access from home. The difference was that it was not done in a vacuum. I could discuss concerns, get pointers and tips to interesting sites and generally get more feedback than is possible logged on to the computer from home. One can certainly get this kind of feedback on-line, but perhaps it is simply that I harbour the old fashioned belief in the joy of ‘touching flesh’. The other factor that must be taken into account is that it is specifically in the ‘conference’ environment that one takes the time to see new work. At Home or in The Office, I simply always find that other things have more urgency.

Telepolis [http://www.heise.de/tp] in association with Rhizome [http://www.rhizome.com/] set up an interactive ‘newsroom’ at the EMAF. The room was the hub of liveliness and activity during the conference. Flitting between video screenings live performances and lectures, the space was a haven and a place to stop, enjoy a coffee, a chat and a space to log on. (I would have to say that my favourite was the fabulously quirky and witty work of Shu Lea Cheang: a whimsical meandering through Tokyo with a gorgeous group of young women—almost an homage to soft porn Japanese style.)

In fact, the on-line facilities at this year’s EMAF were fantastic: plenty of terminals, people milling around trying to get access to telnet sessions to check email. While on the one hand this points to an obsession with having to check what is happening in one’s own world, it was done in an atmosphere congenial to generating discussion and talking with old and new acquaintances about their views on the exhibition and the place of on-line technologies. And of course, telnetting to Australia was so slow that it was easy to keep a track of what was happening (or not happening) on screen at the same time as having a conversation.

Unfortunately, the issue of resourcing, already alluded to, has meant that while the concept behind the newsroom was sound, the actual content which made it onto the newsroom site is not what might have been expected given the talents of the people managing its maintenance: the site certainly in no way reflects the considered critical nature of parts of the telepolis site nor the newsy relevance of the Rhizome site, both of which are dedicated to the discussion of new media, albeit in different formats.

But on to ISEA, where unfortunately, and again for resourcing reasons rather than any will or desire on the part of the organisers of the conference, there was no space dedicated to accessing the internet. Whilst it may seem at odds with the notion of a real time conference that these facilities are necessary, the fact remains that computer screens are not the single-person spaces of interaction they are so often posited. However DEAF [http://www.v2.nl/DEAF – expired] was working with ISEA to stage this year’s manifestation of the event and the internet facility at that event, Digital Dive, was a continuous hive of activity from opening time mid-morning until around midnight, when conference attendees, drinks in hand, would stand around a communal terminal and converse about their most recent site discovery or lament the long download times of their favourite site.

On a very personal front, Kathy Rae Huffman’s On-line Encounters, Intimacy and E~motion at DEAF and Julianne Pierce’s forum with Stelarc and Sandy Stone at ISEA engaged with the personal and the sexual in on-line environments, alluding to new ways of perceiving the body in the realm of ‘cyberspace’.

Stelarc too performed his recent Ping Body [http://www.merlin.com.au/stelarc – expired] at the joint opening of DEAF and ISEA. This work is a natural progression from his wired body performances, but in this performance he takes the body on-line, or rather, the body becomes influenced by on-line activity: his body movements are not controlled by his own nervous system but by the external datasystem of the internet, with internet-activated muscle stimulators monitoring signals to various internet servers.

In the exhibition presented as part of the DEAF event, Daniela Alia Plewe took the internet analogy one step further. A water bed in the middle of a darkened gallery room invited the viewer to lie down and relax. Next to the bed, which more closely resembled a psychiatrist’s couch (or is it just that I have become used to a double bed?) was a computer. The computer activated a large projected image of a text based interface. The interface operated much as text based internet environments do. Like on-line text based environments the texts to which the viewer was invited to contribute became part of a network of ideas and associations which were neither predetermined nor quite arbitrary: it was an amalgam of all of the texts entered by previous visitors.

Knowbotic Research [http://www.t0.or.at/~krcf/ – expired], in the commissioned piece Anonymous Mutterings, also used the internet as one of a range of ways to interact with the light and sound event which almost encompassed the Dutch Institute of Architecture in Rotterdam. The digital sound component of the installation, which one could hear blocks away from the site (a useful bearing in an unfamiliar city), could be manipulated via an interface on the website of DEAF96, and also by ‘bending’ and ‘folding’ rubber mats located at various points around the building. Whilst the work was spectacular in its form, and Knowbotic Research were attempting to use the ‘fault line’ between the Net and the World to produce hybrid domains, the effects of the interaction on the audience were less clear.

One of the most engaging ‘performers’ at all three of these events was Margarete Jahrmann. Her on-line projects, which she undertakes with a range of collaborateurs, are almost perverse deconstructions or perhaps reconstructions of the world wide web. Most particularly the work she has done with Max Moswitzer as “Mamax” [http://www.konsum.co.at/ – expired], [http://www.t0.or.at/~max/mamax.html – expired] or [http:www.silverserver.co.at/mamax/ – expired] undermines the “Gatesian” simplicity of many internet or, more specifically, world wide web interfaces by offering new ways of getting to the source of the information, often laying bare the root structure or ‘filing system’ of the web site and offering that up as an example of its simultaneous simplicity and complexity.

One of the final events of the DEAF festival, which I was unfortunately not able to stay around for, was a forum titled Reflective Responses: Networks, Criticism and Discourse organised by Tim Druckrey. The objectives of this discussion were “to think about the ramifications of distributed information in an historical perspective and in forms that are both dynamic and considered;… to confront and incite an approach to web criticism across a range of topics; and [to]…discuss networked discourse as a fundamental issue of the political, intellectual and theoretical consequences of network ideology…”. I look forward to seeing some of this discussion go on-line.

RealTime issue #16 Dec-Jan 1996 pg. 20

© Amanda McDonald-Crowley; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

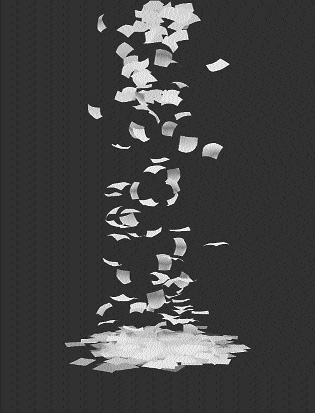

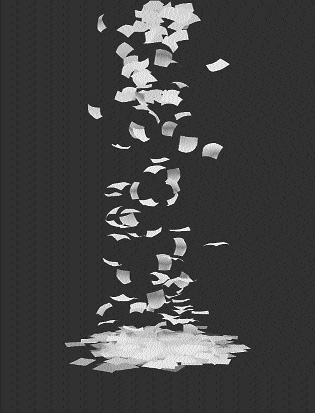

still from John Tonkin’s these are the days

Elastic Light is a program of short computer animation works curated by Jon McCormack, to coincide with the exhibition of his interactive laser-disc work Turbulence at the AGNSW.

Animators have always been fascinated by the ease with which they could produce movement, and the ways in which the movements made by an image could be crossed by movements created through the plasticity of the form itself. Stretching, speeding, crashing and metamorphosing were the favourite activities of the cartoon character. With digitisation, the complexity of the visual possibilities was multiplied beyond measure; animators became intoxicated with it. Techno-baroque was the pervading genre for a few years, and its multi-layering of multi-coloured, omni-kinetic compositions was far more gratifying for creators than spectators of the works. Jon McCormack’s work brings concentration back into the picture. His complexity is not mere complication, the accumulation of multiple visual possibilities. It is highly selective and committed to detail, so that evolving formations on the screen explode into new intricacies of colour and movement whilst maintaining a sustained conceptual focus. Action is always an unfolding, never an arbitrarily added ingredient. Jon McCormack is a hard act to follow. After standing in a darkened space at the AGNSW for half an hour or so watching Turbulence, I took the escalator downstairs wondering how anything else could measure up. It didn’t, but Elastic Light provided some valuable context for what may be the culminating example of the first phase in the first generation of computerised animation. McCormack’s work takes the art into a new order of complexity by adopting the principle of emergence. The algorithm is the DNA of a digital idea which is allowed to develop and proliferate itself as a complex of ever evolving formations.

His choice of works for Elastic Light shows, he admits, a personal bias. But this is where it is interesting. Hanging around in the vocabulary and program notes is an evolutionary theory of animation. The program might well have been subtitled “Climbing Mount Improbable” with its Dawkins-esque commitment to making poetry out of a clinically technical discipline and its talk of “peaks” in the repertoire. A prefatory quotation from Vilem Flusser predicts a new level of existence for homo sapiens, heralded by those “who possess the new imagination”. Are we leaving the manic dizziness of techno-baroque for another kind of dizziness: the dizziness of an art married to science and heading for the heights of unprecedented human achievement? I hope not. I think there is something new happening here, and something with long-term potential but it should avoid making neo-romantic claims for itself. Its origins in John Whitney’s Experiment in Motion Graphics (1969) are described in an authorial voice that is almost comically prosaic. “My name is John Whitney”, the voice-over starts. And the camera, situated politely behind John Whitney’s shoulder, shows us the scientist at work with his light pen on a screen filled with columns of figures. He is not about to get carried away. “All that you see here should impinge upon the emotions directly” but “I must say that to get emotionally involved with the computer is not easy.” Whitney is playing with nothing so dramatic as turbulence. His research project is “Permutations”, a modest exercise in the creation of computerised non-centric movement patterns. The ghost of a future chaos principle hovers dimly as you see diving spirals go through a non-repeating choreography. It would be easy, from this short film, to read Whitney as a boffin whose literal-mindedness and naive references to art-as-emotion have a certain chunky charm for the hip-hoppers of the digital age. Whitney was nothing of the sort. He brought to computer animation a highly sophisticated and carefully schooled understanding of musical composition, and his approach to the creation of visual movement reflected a fascination with the developmental principles of “movements” in music. He sold experimental film works to the Museum of Modern Art in the 1940s and was awarded a Guggenheim fellowship early in his career. As the pioneer of a paradigm shift in the visualisation of movement, though, he remains engagingly perplexed at his own disintoxication.

The rest of the program comprised recent works. John Tonkin’s these are the days, which McCormack describes as “a meditation on the passage of time”, follows Whitney’s systematic example. With its companion work air, water part 2 (also in the elastic light program) it is a formal and restrained experiment in a minimalist format. In the first work, squares of white paper fall vertically across the screen, creating random patterns first through the air and then on the ground. The only hint of poetic indulgence is in the creation of a watery visual atmosphere with blue depths and area lighting. The second “movement” picks out floating squares with coloured light—yellow, then red, then green—to a sound track of cello playing. When I Was Six (Michelle Robinson) also experiments with the possibilities of atmospheric lighting. Furniture lit at a low angle, with distended shadows, moves around a deserted room. A chair creeps about like a spider. The child’s eye view magnifies and dramatises. Movement is the beginning of any form of haunting. “All you see here should impinge on the emotions directly.” It does.

A number of other works in the program are restrained formal experiments: Stripe Box (Kazuma Morino), Just Water (Evangelina Sirgado de Sousa), Memory of Maholy-Nagy (Tamás Waliczky). Superstars (Thomas Bayrle) moves formality towards the visual joke, making cellular image fabrics from multiple repetitions of micro-images, contoured into faces. The micro images zoom in occasionally, revealing body parts, including genitalia (with accompanying orgasmic noises). Jokes are too easy in this medium, so the tolerance level is low. Brain Massage with Robo-Insects is a clever piece of grotesque visual comedy, with mosquito-robots interfering in the work of a team of brain surgeons, but I’m not sure why it gets a place in this program, unless on the variety principle. Ian Bird’s Liberation, a video animation made for the Pet Shop Boys, comes closest to techno-baroque, but redeems itself from the generic mise-en-abîme by playing a sustained game with vertical perspective that, technically speaking, is state of the art.

McCormack’s own work combines the ambitious spectacle of Bird’s approach with the lyrical concentration of Tonkin’s or de Sousa’s. The shift from an interest in form (as a given visual idea) to an interest in formation (as the visible patterns of a continually transitional process of growth) marks McCormack’s work as the start of a new kind of animation experiment and, potentially, a new approach to visualisation itself. It’s illuminating to see this shift taking place through the work of a number of artists committed to less consciously ambitious agendas.

elastic light, curated by Jon McCormack for Sydney Intermedia Network, Art Gallery of New South Wales, October 5 and 12 to coincide with the exhibition of his work Turbulence.

RealTime issue #16 Dec-Jan 1996 pg. 18

© Jane Mills; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Lucy Guerin and Rebecca Hilton in Incarnadine

photo Manuella Cifra

Lucy Guerin and Rebecca Hilton in Incarnadine

Melbourne audiences have had a memorable combination of dance performances over the past few months. One of the highlights was the return to Melbourne by choreographers Lucy Guerin and Sue Healey. Both presenting concerts in September, they gave us an opportunity to look at how differently their choreographies have developed.

Both were part of Danceworks during the 1980s. Since then Lucy Guerin has been in New York, and Sue Healey spent part of that time as the Artistic Director of Vis-a-Vis Dance Company in Canberra.

We have seen glimpses of Healey’s work in Melbourne over that time, but nothing of Guerin. Healey’s Suite Slipp’d, comprised four pieces: two by her, one from Phillip Adams (Australian dancer, based in New York) and a short work from Irene Hultman, New York-based Swedish choreographer, with whom Adams performs.

Suite Slipp’d, Healey’s opening dance, describes exactly what happens in the piece. A collection of short solos, twosomes and threesomes that dip into and borrow from social and historical dance forms. These fragments are picked and pasted, and re-presented as a dense work, almost over-filled with movement. Healey, Adams and Michelle Heaven wind decoratively and decorously through the space with taut, restrained bodies. Sometimes they are twisting like corkscrews. At other times there are bent, angled knees, and half diamond shapes in the arms, by the side of the body, or above the head. Tight spatial patterning is enhanced by direction changes that cut through the air. The performers are close but rarely touch. One can feel the connection between them. There is a magnetism that keep these bodies together.

The tension in Suite Slipp’d is in and between the performers’ bodies, while in Guerin’s Incarnadine, a tension is set up between the performers and the audience. At times, it was as if one was watching this work through a transparent barrier. Guerin sets up a scenario that demands our empathy, but denies us the emotional access to it. Guerin and Rebecca Hilton perform a tireless unison boundary-marking pattern on matching white spirals painted onto the floor. The sound by James Lo crashes and crackles around the dancers, while the stark white light dramatically changes direction, striking the dancers at odd angles. They are exposed by the light. They rarely leave their spirals, perhaps only to extend a movement onto the floor; but they retreat, eager it seems, to maintain their space.

They are approached by a trio (Ros Warby, Nicole Bishop and Jennifer Weaver). The relationship between the two groups is unclear. The trio seem keen to be acknowledged, initially without response. In the final resolve, an uneasy one, we see all five dancers spaced across the stage, their torsos writhing and reaching in unison, stretching towards us, just out of our emotional reach.

Healey’s second work Hark Back is an expedition through an intimate personal history. It feels loose and inviting, like memories that flutter and tease. It is easy to find a way in. There are moments of lucidity, of intimacy, of insight and of sadness. It is engagingly performed by five dancers (Adams, Heaven, Shona Erskine, Sally Smith, David Tyndall) in episodes that create a layered understanding rather than a sequential pattern.

Guerin’s second work, Courtabie 1966, is also, I suspect, a reflection on times past. She presents three young girls (herself, Hilton and Warby), inexperience exposed at every gawky elbow and hip. We journey with them through time and their changing relationships. The use of repeated spatial motifs in this work, unnecessarily exposes the structure. However, Guerin uses subtle changes in rhythmic structure and syncopation which create some playful movement dialogues aptly describing her intention. She also has a way of drawing us to where the movement is in the body, even if it’s just in the fingers of one hand.

There are more differences than similarities between the two choreographers’ work. Healey’s time seems thick with movement. She creates worlds that meander through the short sections of both her works. Guerin is more direct, her stories unfold along a linear path. There is a deliberateness about every movement, a spareness infused with emotional undercurrents.

The inspired performances by the dancers in both Guerin and Healey’s work ably showed the two as strong and distinctive choreographies in Melbourne’s multifarious dance community.

–

Incarnadine choreographed by Lucy Guerin, Gasworks Theatre, September 4; Suite Slipp’d by Sue Healey and Dancers, Beckett Theatre, September 18.

RealTime issue #16 Dec-Jan 1996 pg. 10

© Wendy Lasica; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Molissa Fenley

photo

Molissa Fenley

From New York Molissa Fenley describes her Sydney Festival program to Keith Gallasch

Molissa Fenley, a leading US dancer and choreographer, has made a number of significant visits to Australia. She has worked with many prominent composers including Laurie Anderson, Pauline Oliveros, Alvin Lucier and Phillip Glass and has performed in the US to works by Australian Robert Lloyd. She has collaborated with visual artists including Richard Serra, Richard Long and Tatsuo Miyajima. Her vision of dance as sculpture and dance as ritual has heightened the contemplative and spiritual dimension of her work over the last decade.

KG The significance of this visit is tied to the Keith Haring exhibition at The Museum of Contemporary Art. You were a close friend of his and a collaborator?

MF When we were very young we did a piece together in 1977 or 1978 called Video Clone and it was actually done as a video and as a dance performance. It premiered at the School of Visual Arts. It was only done once but the tape exists and I’m bringing it with me to show and talk about it.

KG So we’ll see the tape but not the dance performance?

MF I was all of 22 or 23 or something. It was a long time ago. I’ll speak about our relationship, how the piece came about and probably a little bit about Keith’s continued interest in dance and how I feel about…you know, when you first start working. I think I came to New York when I was 21 and started working right away. So it was just at the beginning of what it is to be a professional artist in New York and we were both forging our way. He at the time was affiliated with the School of Visual Arts and I was a floating choreographer. So it was interesting to be able to support each other. Our main interaction was back in those early days but when he died I was asked to perform at his memorial and I made a dance specifically for him, which I will be performing in Sydney.

KG You mentioned that Keith Haring had a continuing interest in dance. How did that manifest itself?

MF He was very interested in street dance, particularly, and capoeira and break dance. He had a place called The Paradise Garage which was basically a dance place where people would go and dance till the wee hours. He worked with Bill T. Jones and Arnie Zane with set design. I think basically his interest was in street culture and whatever that meant.

KG You performed this piece, Bardo on the same program as your solo version of the The Rite of Spring at the Joyce Theatre in 1990.

MF I’d been asked to do something for the memorial service that took place at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine here in New York. The Bardo is a Tibetan concept. It’s a forty-nine day period in which, upon a person’s death, they travel through their own personal Bardo, meeting their karma, and in that time decisions about their rebirth are made. So it’s supposedly a seven week period of walking through an intermediate state. So I thought it would be interesting to make something that had to do with that feeling that he had died but he was still very much a part of us. Still is. He’s very important for the continuance of art for a lot of people. He was very influential. In the dance there are lots of references to his funny little shapes. I mean they’re recognisable to me and probably to anyone who knows his work well.

KG So do you embody these concretely?

MF An occasional gesture. An implication, I would say.

KG For close to a decade, a number of writers have described your work as spiritual, ritualistic, contemplative.

MF Bardo is quite the epitome of all those things.

KG That’s an ongoing part of your work?

MF I’d say so. I think the range of my work is quite large. There are still pieces in my repertoire that are very spatial and dance oriented and then there are pieces that are more sculptural, which I think Bardo is. I like to keep shifting back and forth between them. So for the performances in Sydney I’ll be doing three different pieces: one that’s quite sculptural, and a piece that moves through space quite largely, and then Bardo.

KG So as well as the contemplative, sculptural work there is still some of that particular kind of energy I would have seen years ago when you performed Hemispheres at the Adelaide Festival?

MF Well that was 1983. So things change and shift around. But I would say that the energy of that early work is present in a changed way and I’m not sure exactly what that change is—I don’t think the work is as fast as it used to be.

KG With the Peter Garland and the Lou Harrison pieces in the MCA-Festival program, did you commission these or did you work from extant music?

MF Both of them are existing pieces. But when I work with composers I always ask them what they think I should use and establish a real relationship with them. I don’t just pick up the CD.

KG How would you describe these two pieces?

MF Savannah is a work to Peter Garland’s composition and it has the feeling of taking a walk through the savannah which is a geological area of grassland with an tree here or there. There’s a calmness to it but a lot of dance motifs within. It’s quite an abstract work. Pola’a is the piece to the Lou Harrison music. ‘Pola’a’ is an Hawaiian word for a quality pertaining to the ocean. It’s a quiet ocean, not a huge raging sea. It deals with ideas of ebb and flow, tides, surgings and swellings. It’s a very large piece moving through space, very much inspired by the idea of the ocean and different types of tides…and the idea of the music itself, which is very inspiring. I work very differently with each piece but I would say that with the Lou Harrison I work very much hand in hand with the music, and with Savannah I worked on the dance first and then the music seemed to be appropriate for the work…and the same with Bardo—I found Somei Satoh’s music after I’d started working on it.

Molissa Fenley has recently created her own web page: www.diacenter.org/fenley. She describes it as a dance piece for the web working on the dance and sculpture relationship thant intrigues her. It was created with the assistance of the Dia Center for the Arts in New York.

Molissa Fenley, American Express Foundation Hall, Museum of Contemporary Art, January 14 and 15, 9.00pm; Video Clones screening and talk, January 16, 6.00pm.

RealTime issue #16 Dec-Jan 1996 pg. 3

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

When the man behind me in the stalls at Melbourne’s State Theatre asked his Chinese companion if The White-Haired Girl was a well-known story in China, I was praying she’d at least ask him if Swan Lake was a well-known story in Australia. But, of course, she gave him a very courteous Chinese reply. At the risk of being misunderstood I tried to turn round and get a peek at how old she was—perhaps she didn’t know much about the work either. They used to say, in the aftermath of the Cultural Revolution, that 800 million people had seen only eight plays for eight years and the ‘revolutionary modern ballet’ (now styled ‘classic modern ballet’), The White-Haired Girl, was one of them. Yet it would be quite wrong to think everyone got to see a live performance, since it was extremely difficult to get tickets, and most Chinese I have spoken to saw only the film version—which they loved. The problem was never that the work was propaganda only that it was part of a very limited repertoire of propaganda. So, for me, who saw some of these works in the 70s as a privileged foreign visitor, and my Chinese friend who saw films of them, this was a very exciting occasion, although there is little in the Shanghai Ballet’s promotion that would prepare you for it.

In fact, this is one of two ballets in the famous repertoire, the other being Red Detachment of Women, which is regarded as a technically superior work. The great thing about The White-Haired Girl however is its folkloric power, the fact that it had already taken its place in Chinese culture as a legend, factual story and opera (and black-and-white film of the opera) before becoming a model opera in the 1960s.

This is the work Jiang Qing (Madame Mao) must surely have felt most ambivalent about, since it was a kind of ghost story, and she was always determined superstition would be rooted out of the Chinese theatre, which had long been a haven for fox-fairies, snake goddesses and erotically inclined transmigratory souls. She may also have had strong feelings about the storyline, which is reminiscent of her own life. She hinted to her biographer, Roxane Witke, that her mother was forced into prostitution—that she became accustomed from an early age to ‘walking in the dark’ in search of her mother. Her fear and loathing of dogs is also suggested both in official biography and in the roman-à-clef novel Red Azalea, in which the body of a fallen woman, being unsuitable for burial with her ancestors, is interred outside the city gate where her bones are gnawed by wolves. All this fits with The White-Haired Girl, which is based on the Chinese legend of hungry ghosts, the vagabond undead who plague the living unless they are offered sacrifices like other respectable spirits with decent filial descendants.

Jiang Qing actually played a starring role in a 1936 film called Blood on Wolf Mountain based on a novel, Cold Moon and Wolf’s Breath, in which a community of human beings triumphs over marauding wolves—the Japanese. The White-Haired Girl is set in northern China before the organisation of resistance to the Japanese invasion. In the 1940s opera which preceded the ballet (and won the 1951 Stalin Prize for Literature), the peasant girl Xi’er is sold to a landlord against the will of her father, abused by the landlord’s mother, made pregnant and then thrown out of the house to be remaindered as a prostitute. She flees into the mountains and becomes a white-haired, cave dwelling spirit, frightening local peasants who take her for a hungry ghost to be offered food sacrifices. In her wiId outcast state, she is constantly threatened by the elements, and in the ballet version we see this luminous, ragged-maned creature darting eerily through rain and lightning, always a step away from howling wolves and their human incarnation—rapacious landlords and their feudal lackeys.

Finally she is discovered and redeemed by members of the Communist Eighth Route Army, who do not believe in ghosts. As Marxists and materialists they appreciate that her white hair is simply the result of a lack of salt and sunshine. She emerges from her cave into the brilliant sunlight—also the symbol for Mao Zedong—and stands with her comrades in a famous last act tableau celebrating her unmasking and metamorphosis from mysterious renegade ‘animal’ outcast to member of the new proletarian, human family. In the ballet version there are a number of changes but the major one is her repulsion of the landlord’s attacks—this heroine cannot be sullied, which is not good news for real rape victims.

In the 1950s, before the ballet was created, there was considerable theoretical discussion about realism in literature, and Xi’er—the white-haired girl—was seen by some as a character who demonstrated the ‘typical’ qualities required of a proletarian hero without sacrificing distinct individuality. At this point she was still real enough to be raped, become pregnant and have a child—and her father was real enough to commit suicide. She was described by one critic and writer—soon to be denounced as a rightist during the Hundred Flowers Movement—as “an ordinary girl with an unusual destiny”.

That she managed to live down her association with rightist theoreticians is an indication Xi’er may well have had genuine supernatural abilities. In fact, during the Cultural Revolution she became a pin-up girl, and her picture was pressed lovingly into boys’ wallets; but, in spite of this dangerous habit, she remained an untouchable symbol of proletarian purity. Curiously, in the ballet, more than in the opera, there is a strong hint of that kind of U.R.S.T (‘Un-Resolved Sexual Tension’) beloved of modern television scriptwriters, although, it must be said, this ghost does get laid. Revolutionary Romanticism steers perilously close to True Romance at times and there is a lovely sensuality about this moonlit apparition in her papercut, Peter Pan-ish costume—the garment of the tale gapes, as Roland Barthes would have said. On top of it all there is a suggestion of primitivism and even ‘Fauvism’ which Jiang Qing specifically denounced in one of her key speeches on the arts. Yet this is the model work which suffered the least interference from Jiang Qing, the relentless censor and inquisitor.

There is a good deal of the world’s folklore, ancient and modern, about The White-Haired Girl; lupine themes have been appropriated from peasant story-tellers for use as moral education for bourgeois audiences (a similar thing happened to Little Red Riding Hood); familiar motifs of starvation, rape (the Neapolitan version of Sleeping Beauty), child-selling (Rumpelstiltskin), and banishment to the wilderness (Rapunzel), are apparent. Perhaps, with European ballet and music wedded to Peking Opera movement, with traditional folk storyline and the use of modern peasant protagonists, Jiang Qing succeeded, in spite of the ideological difficulties presented by this story, in creating the international proletarian fairytale.

The German Marxist Walter Benjamin said fairytales told us of “the earliest arrangements that mankind made to shake off the nightmare which the myth had placed upon its chest”. The wicked witch is dead, but in The White Haired Girl we may still see Jiang Qing’s attempt to get the nightmare of truth off her chest and transform it into the power of fairytale.

RealTime issue #16 Dec-Jan 1996 pg. 9

© Trevor Hay; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

The curtain is up as we enter. Two figures hang in perspex cubes: specimens, a sacrifice; naked but preserved, elevated, ready for dissection. Below, dancers stretch, flex, finalise, in a casual yet definite rhythmic pattern. This backstage is already on show.

This is the pause before the dream; the curtain falls, slicing the space between watcher and dance. A colonnade opens, a male body revealed in yogic contortion, his outside turning in. His hand gestures like Dylan Thomas’ green fuse up through an impossible space between his limbs.

To his side, a woman dances within the curtain—embraced and writhing. They dance the edge between out and in, the membrane between past, present and dream. And as if the membrane, the question of the border, becomes another person, another single figure appears…

Jiri Kylian’s Bella Figura is a neo-Renaissance work with a Mannerist questioning of the givens in classical repertoire. If we associate Renaissance with man-centredness, stone colonnades, chiaroscuro lighting, and the ambivalent relationship between full skirts and the nakedness of Da Vinci’s anatomies, then Kylian’s work is not so much about partnering (that on which classical dance technically relies) as about the duality of performing and being. One partners, is partnered, and yet one is technically quite alone. Such dualism is achingly apparent in the music (Pergolesi, Torelli, Marcello, Foss—a pair of ears takes in a macrocosm of sound), in yoga (where postures and sensations consolidate and expand the body’s references), and in dance, where the dichotomies of gravity and defiance, muscle and lightness are taken further into a questioning of how contemporary bodies can dance old themes.

The choreography continually toys with these aspects: partners dance whilst the presence of a third questions from the side, in pyramids of light merging or emerging from a dark Roman corridor.

Even the most classically-oriented lifts are re-coloured mid-air by a crossing of knees, or thighs registering a contrapuntal trill. Body positions encompass classical, Renaissance court dance, occasionally something like flamenco, as well as animal, insect and dream.

Against the hilariously human (a dancer sliding cross-stage to land beneath his lover’s knees), a man “walks” a woman like a greyhound beside him; he, huge, falls to amble beside her like a Great Dane. Their passage cross-stage is a slipping-off of human covering. Costumes, too, play with this slippage: a woman’s upper torso is bare, below she is full-skirted with red. She is a rose: powerful, vulnerable, scented with knowledge beyond the billowing and seams.

This aspect of framing, clothing, and revealing becomes astonishing when six half-naked courtiers downstage cradle the long curtain, the sky itself ruched in their arms. Their skirts dance, embracing the collusion of the spheres; and then the sky itself begins to fall, the curtain bar falling into their velvet dreams.

Is this the beginning or the end? Two hug a curtain to each side; is this the start or finish of the dream?

* * *

A pair come in for curtain-call amidst a line of braziers aflame. Their bodies lean towards the heat. Their duet is almost classical; his lift (her legs paddling like a swan’s) ends with her lowering leg sliding over his ankle like a swan’s neck’s embrace.

He masks and stops her mouth as he supports her turn. It is their last illicit meeting: each soothes the other’s shoulder hitching with sadness. A silent, clandestine pas de deux, they exit, leaving the unspeakable behind.

* * *

Whilst Bella Figura (an Italian term meaning “don’t let on that anything is wrong”) shows trouble drumming beneath the skirt-swept courtyard face of an era, No More Play is a restless if brief dance of pressing contemporary alienation. The costumes and stage are dark and bare. Long black pants, short leotards, Webern’s atonal score giving no hook of comfort tunes. Pyramids of light pick out trio versus duo in a chequerboard of ambiguous relationship and uncertainty.

A woman is held aloft by the legs between two men, taking great strides across the sky. She is gargantuan, but totally reliant on her supporters.

There is an edge of trepidation: confounding borders, dancers roll and hang over the front edge of the stage. Dancers rock as if blindfolded, smack themselves; limbs form geometries which wrap into themselves, bodies twitch like speared deer.

Kylian, inspired by a Giacometti sculpture, says “one might feel as if one has been invited to a game, the rules of which are being kept secret, or have never been determined”. This short, disturbing piece about the semi-conscious is epilogued by a long, low rumble which leads directly into a surprising, white, corsetted dance where rapiers and partners swap roles.

Petite Morte is a dance of ritualised lust that is both fearful homage to and proud demonstration of the game of love. It expands the scene from Bella Figura where a duet play bow-and-arrow, stretching and arching at antelope in a delicate hunt of ordered passion.

Six women’s bare necks and arms are picked out by the opening light, their folded hands white diamonds/chastity belts against black velvet bellies. Before them, six men perform a dance with rapiers that swish and prod and fall; they drop them, also slap their own bodies; rehearse the missionary position and lower themselves over prone rapiers to the floor.

In the chiaroscuro light, their white boned corsets and women’s bodices contrast with the spilt-blood black of velvet abandoned in the colonnades. This is a petite mort of sex and teasing death, swapping rapiers for women then deftly passing the weapon through the women’s legs, an elaborate mating game.

They draw spears through their own bodies like floss through teeth; they enter tipping their skirts, slide cross-stage like soccer players in a toy parlour game.

The humour is timely and unsettling; in the final image, life dances back in black cloak: six empty skirts enter, spinning and rotating on their own, red on the inside like the blood that has left the dancers’ bodies and dared itself to dance alone.

Kylian’s choreography is a relief from the usual sexing of dancer’s bodies to either the crass, the pristine, or machismo. Men join a chorus of skirts, a woman partners a man as if she’s a boy; whilst women’s hips swerve and curve like sliding gazelles, men refrain from piercing leaps but hold the horizontal with the level swaying power of poppy blooms.

This is a huge beauty that doesn’t need to boast muscle or brawn but plays the edge of doubt, mask and intrigue that performance has long known but doesn’t always dare to show.

Bella Figura, No More Play, Petite Mort, choreographed by Jiri Kylian, Melbourne International Festival of the Arts, State Theatre, October 29. (The program also included Fantasia choreographed by Hans van Manen—not reviewed here.)

RealTime issue #16 Dec-Jan 1996 pg. 12

© Suzanne Spunner; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

From the 50th Edinburgh Festival and Fringe, Benedict Andrews conjures performances by Wilson, Bausch, Stein, Chaikin, Netherlands Dance Theatre, Hakutobo, Zofia Kalinska and Teatr Podrozy

In order to celebrate the 50th birthday of Edinburgh Festival, director Brian McMasters invited a core of elite theatre and dance artists to present works. As a young director this was a rare opportunity to see my heroes in action—Robert Wilson, Pina Bausch, Peter Stein and Robert LePage. With the cancellation of LePage’s Elsinore due to equipment failure and of Neil Bartlett’s Seven Sacraments due to illness, the Festival lost two of its brightest young stars. Their works promised a questioning of the boundaries of theatre and a meshing of performance with other forms—cinema and digital technology in Elsinore and the visual arts in Seven Sacraments. The Festival, instead, became a display of established auteurs.

The high priest of hi-tech aestheticism, Robert Wilson brought two productions that showed the present extremities of his work and a seeming fascination with the Modernist textuality via the high-fiction of Virginia Woolf’s Orlando and the playful, heavenly landscapes of the Gertrude Stein-Virgil Thomson Four Saints in Three Acts. Both productions were abstract and mesmeric. Orlando was a minimalist chiaroscuro composition with an epic solo performance from Miranda Richardson, and Four Saints a lollipop landscape saturated with cartoon colours and filled with flying sheep, elegant giraffes, punk acrobats and a chorus of sartorial saints and vaudeville comperes.

Orlando is a fascinating exemplar of Wilson’s recent experiments with narrative showing his refusal to illustrate text or display conventional emotion. Instead he writes a parallel text with gesture, architecture and light, which forces the audience to drop below the narrative and let its dream logic unfold. Woolf’s fantastical tale about a young lord who lives through 350 years of history and finds himself transformed into a woman is perfect fodder for Wilson’s explorations of time’s passing and history’s images. Orlando is performed by Richardson with androgynous tension and physical and vocal precision. Her voice is amplified giving it a mediated resonance and an alien-like quality. As words pile on top of words in her two-hour monologue, Richardson’s voice and Woolf’s language are fused into an independent and mercurial texture. Hans Peter Kuhn’s meticulous sound design allows Orlando’s voice to shift through speakers placed throughout the auditorium further accentuating the character’s disembodiment. Wilson’s lighting design draws inspiration from German Expressionist films and early Hollywood. At the beginning the stage is black, a light picks out the back of Richardson’s head for a moment, fades to black again, then lights her hand only. Parts of her body seem to float. Wilson continues to make light a performer throughout the piece, often using it to play with appearances and disappearances central to the questionings of identity and sexuality in the text. The light is always sculptural with tight follow spots lighting Richardson’s face, making her seem like a haunted Greta Garbo.

The space is a cross between minimalist painting and magic show. Wilson flies various gauzes and curtains to change compositions, creating chambers and multiple horizon lines. He also uses the set as a sequence of indices, which play with scale and meaning. A miniature automated door pops up through the floor to represent Orlando’s suitor, opening and closing in response to her questions. When Orlando changes into a woman, s/he does so behind a giant polished metal tree trunk which has slowly flown in. This phallic joke and pun on theatrical conventions demonstrates Wilson’s oblique and playful dramaturgy. His Orlando uses form to interrogate language and subjectivity. Richardson’s performance moulded into Wilson’s statuesque choreography shows the impact of history and time on the body.

Gertrude Stein and Virgil Thomson’s cubist opera Four Saints in Three Acts provides Wilson with a language that converges with his own use of autistic text, allowing him to create hallucinatory landscapes. He calls the piece “a meditation on the joy of life.” It is a series of free-associative pictures as various saints graze in a day-glo heaven. Snow falls on white cutout palm trees, biplanes fly by, angel statues drop in and giraffes bow their heads. It is classic make-of-it-what-you-will Wilson surrealism culminating with a ‘mansion of heaven’ (a giant white architectural model suspended above the stage) bursting into flames as the saints on stage hold miniature models in their hands. These are the light and beautiful ‘souls’ reflected on by Wilson and Stein in their meditation on saintliness, or ‘genius’ if you like.

Peter Stein’s production of Uncle Vanya with the Teatro di Roma and Teatro di Parma was the closest the Festival came to a well-made play (with the exception of Botho Strauss’ wonderfully well-unmade play Time and the Room presented by Nottingham Playhouse). Uncle Vanya is a masterpiece of orchestration combining passionate realism, hyper-naturalistic design and an ever-present soundscape, which highlights Stein’s inspired use of silence. Over three and a half hours he creates a terrifying passage of time within which the characters’ gradual disintegration and painful tearing of illusions are played out. The performances from the cast of handpicked Italian actors are detailed, yet elastic. Each character proceeds blindly from an unresolvable, unknowable lack; the impossibility of resolution fused with an acute awareness of the body’s aging creates a slow dance of death. Stein sees the play as containing the embryonic symptoms of all the systems and neuroses of the twentieth century. In this way his exacting analysis and evocation of the emotional lives of Chekov’s Russian bourgeois becomes an exploration of our own fin-de-siecle malaise.