Isaac Julien's carnival at the MCA

Jane Mills

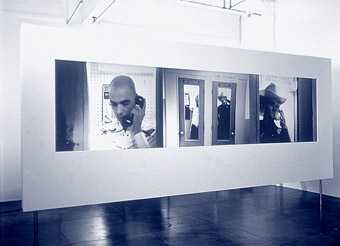

Isaac Julien, The Long Road to Mazatlàn

It seems that barely a week goes by without an attack on Sydney’s Museum of Contemporary Art. In late February it was Premier Bob Carr’s turn. His complaints about the museum’s international standing and poor quality of its collection and exhibitions drew an instant, wounded response from its outspoken director Liz Ann Macgregor. She need have done no more than point Carr towards the MCA’s current exhibition The Film Art of Isaac Julien.

This display of film, video-installations, photographs and prints, with its suggestions for new narrative possibilities and ambiguous imagery, bestowed mental traces that uncannily haunted me for days, compelling me to revisit the (free) exhibition. Ghostly memories aren’t easily tracked down, so I had to go yet again. Each time the startling yet dreamlike, strong yet gentle, carnival of Julien’s film art told me something new.

Britain’s pre-eminent Black filmmaker, Julien’s prescient feature Young Soul Rebels (1991) and feature documentary Looking for Langston (1989) anticipated art movements. Young Soul Rebels surely positioned him as one of the provocative band of so-called ‘Young British Artists’, and yet he’s never been included in this group. Langston, with its retrieval of the Harlem poet’s homosexuality and stylistic treatment of history, heralds the homo pomo of New Queer Cinema at least 3 years before it was invented.

Julien is difficult to label perhaps because labelling is, in part, what his art explores. He burrs the boundaries between cinema, painting, video, photography and performance, and rejects stereotypes in a process of metamorphosis by which they re-emerge as icons. He moves confidently between past and present, inviting us to feel repair rather than loss; he achieves this most memorably by casting himself in Langston as the dead poet in his coffin.

This beautifully photographed documentary, which pushes to the limits the definition of the genre, is shown in full on a large screen at the start of the exhibition, setting the tone and touching the right auratic nerve with which to view Julien’s more recent video installation work. His film trilogy, The Attendant (1993), Trussed (1996) and Three (The Conservator’s Dream) (1996-1999), here transferred to DVD, all display extraordinary, powerful images drawn from a sincere engagement with post-colonial, gender, queer and other political and social discourses. The work is assuredly intellectual and, at the same time, provides easily recognizable images that hover between the outright provocative and, without a hint of false sentimentality, the aesthetically romantic.

Giving a lecture to launch the exhibition, Julien expressed admiration for the way in which the MCA had designed the space to display his work. And small wonder. Placed alongside his photos and prints, his videos glow on screens small and large, single and composite, without any sense of competing with each other. The open-endedness of his video installations, as they play on loops, provides a mood of repetition and compulsion that affects, entirely pleasurably, how we view the still images. They, in turn, allow us to see his moving images as a series of stills while the narratives move backwards and forwards from scene to scene, and between screens.

It is impossible to resist a sense of physical interaction with Julien’s work. Feelings of erotic pleasure and loss in Trussed, for example, are enhanced by its projection on 2 screens showing identical, but flipped, images that are set in a corner at right angles. This offers ambivalent resonances of a butterfly struggling to free itself from a Rorschach test. The stunning 3-screen DVD installation The Long Road to Matazatlan delivers frissons of recognition as the fragmented images of a story of unrequited love between 2 cowboys appear stuck in a bizarre salad of Andy Warhol, Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver, road movie and western.

Julien explained his interest in exploring the physical relationship between audiences and film by suggesting that he aimed to “bring back some of the early experience of making films. It’s more like early cinema, when spectators came and went at their own leisure, that open-endedness you don’t find when in a typical single-screen viewing situation. Repetition produces another way of viewing you wouldn’t otherwise get.”

Given its current troubles, it was a bold decision of the MCA to show Julien’s film art, since one of his recurring images is that of the museum as a repressive bastion of white authority. Can it be read as an indication of the MCA’s willingness to reflect upon its own role in helping us (re)define our relationship with screen culture? If so, things look good for the cinematheque which, many of us devoutly hope, the MCA will deliver in the not so distant future.

The Film Art of Isaac Julien, curator Amada Cruz, Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, until April 22; Out Takes, a presentation by Isaac Julien, Mardi Gras Film Festival 2001: A Queer Odyssey, Palace Academy Twin, February 15

RealTime issue #42 April-May 2001 pg. 14