indigenous media art: complex visions

tom redwood: stop(the)gap, adelaide film festival, samstag museum

Warwick Thornton, Stranded, 2011, film still, commissioned by Adelaide Film Festival Investment Fund 2011

© the artist

Warwick Thornton, Stranded, 2011, film still, commissioned by Adelaide Film Festival Investment Fund 2011

AT THE EXHIBITION OPENING, AMID ENDLESS GLASSES OF CHENIN BLANC, THE GUESTS WERE FORTUNATE ENOUGH TO WITNESS A TRADITIONAL KAURNA SMOKING. LOCAL ELDER UNCLE LEWIS O’BRIEN THEN WELCOMED ARTISTS, CURATORS AND GUESTS IN KAURNA LANGUAGE TO STOP(THE)GAP, AN INTERNATIONAL EXHIBITION OF INDIGENOUS MEDIA ARTS, BEFORE ADDING A BRIEF FOOTNOTE IN ENGLISH: “WE HAVE BEEN WELCOMING VISITORS TO OUR LAND FOR THOUSANDS OF YEARS. THE PROBLEM IS WE’VE NEVER TOLD THEM TO GO HOME.” HIS COMMENT MET A GENERAL SILENCE.

A similar frankness runs through curator Brenda L Croft’s introductory essay in the exhibition catalogue. In an aggressive and confessional style Croft outlined her infuriation at being Indigenous and intelligent in a place as heart-poundingly and mind-numbingly stupid as mainstream Australia, where even the most elementary reflection on colonisation and the marginalisation of Indigenous Australians is consistently and wilfully avoided. It was an angry and perhaps reckless decision to share such unrestrained thoughts. For daring to express her outrage in forthright political language Croft was ruthlessly attacked by The Australian’s Christopher Allen in a review less concerned with discussing the artworks on display than with celebrating the writer’s tiresomely cynical politicking.

Such political directness was not, however, to be found in the artworks on display in Stop(the)Gap. Indeed, the exhibition is surprisingly non-confrontational. Something quite different (and often more complex than) direct ideological or political discourses on ‘Indigeneity’ is on offer here. Suggesting no easy answers, or even difficult answers, the conceptual implications of the seven featured artworks (of which I will discuss four) are instead fleeting and poetic, grasped for a moment.

The elusiveness of the artworks on display at Stop(the)Gap points to what might be understood as the exhibition’s determining ethos. Opening the forum held to discuss the exhibition, curator Croft (who coordinated the choices of her overseas guest curators) clearly explained her key goal for the exhibition as a movement (or series of movements) beyond colonial forms of representation towards Indigenous self-representation. And this, of course, means a movement into the unknown. In Croft’s words:

“Indigenous communities around the globe share colonial histories relating to dispossession, injustice, inequity and misrepresentation. Even in the 21st century, indigenous art continues to be negatively configured through the historical contexts of Western art.” Exhibition catalogue.

Alan Michelson’s large four-channel work TwoRow II (2005) stands as an emblematic expression of this ethos. Michelson (a Mowhawk member of the Six Nations) is clearly aware that a large part of the contemporary Indigenous artist’s energy must be spent bending, breaking, transgressing, transcending the constrictive and static representations of Indigeneity perpetuated by colonial discourses. That’s a no-brainer. Michelson is also aware, however, that there are two sides to this agenda. In TwoRow II, two horizontal bands of purple and white images (alluding to a belt woven by the Native American Haudenosaunee people to mark their 1613 treaty with Dutch colonists) denote the two sides of the Grand River in southern Ontario, Canada. One bank is populated by non-Native townships. The other is the site of a Six Nations reserve. Travelling in both directions along the river, the viewer absorbs these juxtaposed rows simultaneously (along with the contrasting Indigenous and non-Indigenous stories and tourist commentary played on loudspeakers).

For Michelson the river both links and divides the Native and the non-Native. Ideas of ‘Coloniality’ (as well as ‘Indigeneity’ or ‘Aboriginality’) must therefore be opened up for questioning. The Colonial and Indigenous are interrelated and in a constant state of change. Quite literally, Michelson’s work keeps moving. The literal two-sidedness of Two Row II undermines the viewer’s desire to focus on one of these sides independently of the other. There is no stationary reference point.

Two other interesting and very different large-scale works came from Canadian artists Rebecca Belmore (of Anishinaabe-Canadian heritage) and Dana Claxton (of the Hunkapa Lakota Sioux nation). Noting their obvious differences, Canadian curator David Garneau (who selected both works for exhibition) emphasised his interest in their paradoxical commonality. Beginning at either end of a hypothetical Indigenous artistic spectrum, Belmore and Claxton seem to be moving towards something in the middle, some common problem or ideal perhaps. This dialectical relationship was emphasised by Croft, who positioned the two works opposite one another on the ground floor of the Samstag Museum.

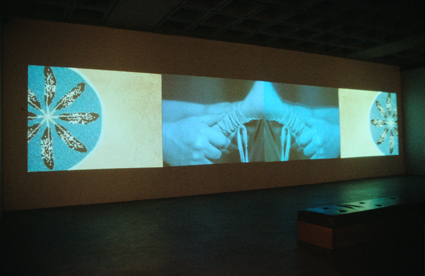

Dana Claxton, Rattle, 2003, installation view

© the artist

Dana Claxton, Rattle, 2003, installation view

At one end, Claxton’s Rattle (2003) is one of the most beautiful examples of installation art in motion I have seen. A difficult work to describe in concrete terms, Rattle is in the artist’s own words “a visual prayer attempting to create infinity…[much] like a palindrome” (catalogue). Across four screens—the inner two mirroring and the outer two mirroring—Claxton offers the viewer-listener a hypnotic and strangely powerful aural-visual experience of perceptual and perpetual rhythm. It is a delicately made and extremely impressive work, of living art over artefact, invoking traditional Sioux singing, music and movement without conceding to any coy idea of the ‘traditional.’

Rebecca Belmore, The Named and the Unnamed, 2002, video installation, Collection of the Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery, The University of British Columbia

photo by Howard Ursuliak, © the artist

Rebecca Belmore, The Named and the Unnamed, 2002, video installation, Collection of the Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery, The University of British Columbia

Rough, handheld and with a markedly street aesthetic, Rebecca Belmore’s The Named and the Unnamed (2002) seems to be everything that Rattle is not, certainly no delicate expression of Indigenous spirituality. Also seemingly the most overtly political work of the exhibition, The Named and the Unnamed is an installation based around Belmore’s performance work Vigil (in fact it is, more or less, a recording of this performance projected onto a wall sparely quilted with small lights perhaps indicative of the women lost—the subject of the work). Approaching performance as a sacred act, Belmore acts out a series of painful rituals on a street corner in downtown Vancouver, a site where many missing and now presumed murdered Indigenous prostitutes worked. It’s not entirely clear as to precisely why the artist performs particular rituals (stripping roses with her teeth, nailing her dress to telephone poles) but that’s how rituals work. In the exhibition notes, Jolene Rickard suggests Belmore’s intent is to set right or balance imbalance (“Rebecca Belmore: Performing Power,” 2005). With no material justice coming from authorities who have shown little interest in pursuing the cases of these poor, marginalised, Indigenous women, Belmore aims at a higher spiritual justice for these young souls in trauma. It is a problematic but also very arresting piece, demonstrating that sacredness has nothing, essentially, to do with style.

Finally, there’s Warwick Thornton’s Stranded —a difficult work to pin down, all the more so coming from the director of the realist masterpiece Samson and Delilah. On entering the space—with 3D glasses and complementary popcorn in hand—we see the artist himself, nailed to a kitsch fluorescent cross that spins slowly, hovering above a richly coloured central Australian landscape with wide open skies and waterholes. At the base of the cross is a skull and crossbones. Dressed in a drover’s outfit (a reference to Aboriginal stockmen?), Thornton seems at first to be feigning an heroic machismo, but then, in close-ups, is revealed as simply drowsy: sleeping, yawning, head slumping. On his chest (in intense close-up) are the bloody traces of a whipping.

The only explanation we are offered in the exhibition notes is that Stranded was inspired by a drawing the artist made when six years old, under which he wrote, “When I grow up I want to be just like Jesus.” Thornton’s decision not to attend the exhibition forum only reinforced a sense of his reluctance to explain anything more about the work. The ironic tone (the ludicrous cross, the costume, the flaccid hero) suggests a playful critique of European Christianity’s influence on First Australians, or of Thornton himself. But that doesn’t seem nearly enough. Perhaps what we are seeing here is the juxtaposition not only of ideologies but of histories: the ‘newness’ of the flash cross (Christianity) highlighted by the ‘ancientness’ of the surroundings (Country, Dreaming). We are also possibly witnessing a representation of a ‘lost’ Aboriginal generation, Thornton’s own, no longer under missionary control, yet still nailed to the cross, detached and hovering above the Land. Perhaps in Stranded we encounter another ‘muddying of the waters:’ art that worries at the line between Indigenous and non-indigenous, elusively pushing beyond established concepts.

If it can be put into words, Stop(the)Gap seems to outgrow old restrictions, naturally and organically, advancing towards new, as yet unformulated conceptions of Indigenous self-representation. The role Brenda Croft assumes as curator is unusually active in this respect. With a second chapter of Stop(the)Gap due for exhibition in various Adelaide gallery spaces in October, Croft envisions the exhibition as spreading worldwide, in a state of continual relocation and reconfiguration.

Stop(the)Gap: International Indigenous arts in motion, curator Brenda L Croft, artists Rebecca Belmore, Dana Claxton, Alan Michelson, Nova Paul, Lisa Reihana, Warwick Thornton, Samstag Museum, Adelaide Film Festival, Feb 24-April 21

RealTime issue #102 April-May 2011 pg. 23