History never repeats

Caroline Wake, with Keith Gallasch and Virginia Baxter

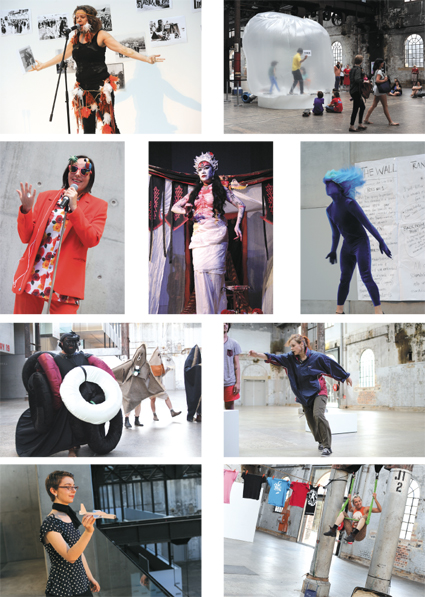

30 Ways with Time & Space. Row 1 – Nadeena Dixon, photo Heidrun Löhr (HL); Clare Britton, Matt Prest and Leslie Britton Prest (HL). Row 2 – Victoria Spence (HL); Rakini Devi, photo Bec Dean; Dean Walsh (HL)

Row 3 – Hossein Ghaemi & collaborators, photo Nic Dorward; Vicky Van Hout & Thomas E Kelly, photo Lucy Parakhina; row 4 – Sandra Carluccio (HL); Simone O’Brien, (HL)

30 Ways with Time & Space. Row 1 – Nadeena Dixon, photo Heidrun Löhr (HL); Clare Britton, Matt Prest and Leslie Britton Prest (HL). Row 2 – Victoria Spence (HL); Rakini Devi, photo Bec Dean; Dean Walsh (HL)

Performance Space is an unwieldy entity: part site, part community, part sensibility and increasingly, a part of history. Its 30th birthday party was bound to be epic and indeed it was: You’re history! was a two-week program that included so many artists and events, it was possible to camp at Carriageworks for the duration and still miss something.

The festival combined three main programs: 30 Ways With Time and Space, a series of performances by artists who have been involved with Performance Space over the years; the Directors’ Cuts, in which former artistic directors were given an hour or so to do as they wished; and a series of new works by Tess de Quincey, Nigel Kellaway, Rosalind Crisp and Brown Council. On a typical night, one might arrive at 6.30pm to see a short performance in the foyer before moving into Bay 20 for a Director’s Cut and then exiting to find another short work underway. Once that had finished, you could see whichever new performance was on or wander into Bay 19 to watch Brown Council’s video artwork. The result was that Carriageworks was occupied and animated by Performance Space and its patrons for the entire two weeks.

Opening Night

On the opening night, Aunty Rhonda Dixon-Grovenor sang a welcome to country before co-directors Bec Dean and Jeff Khan gave their speeches while artist Sandra Carluccio launched tiny balsa planes—on which were written fragments from the archive—from the atrium. Jon Rose and Lucas Abela played a loud and aggressive set that successfully drowned out most conversations, an appropriately uncompromising gesture from an organisation that prefers to challenge rather than comfort its audience. Branch Nebula then took over the foyer to stage a live multiplayer game.

30 Ways with Time & Space

In the 30 Ways program, established artists tended to oscillate between reminiscence and re-enactment, sometimes within the same performance. While slipping in and out of old costumes and performances, Victoria Spence reflected on a vivid life, climaxing in an apocalyptic poem alternating between despair and ironic acceptance:

“We are culturing everything—ourselves, our veggies, our kids, unashamedly/ embracing our bacterial and microbial co-existence./ Culture is literally in our guts and we taste great.”

The audience helped Simone O’Brien dress and undress while she reminisced about infamously and spectacularly pissing from a trapeze in a mid-90s performance. For a moment it looked as if she might christen Carriageworks’ floor but she refrained. To the strains of “Fascination” Clare Grant and Chris Ryan, of Sydney Front fame, performed in trademark slips while they recalled touring Europe with pockets full of Thai baht. Two other Sydney Front members in the audience, John Baylis and Nigel Kellaway, laughed so hard they nearly spilled their wine. Another much loved ensemble, Frumpus, also dug out their favourite costumes, dancing in daggy red tracksuits before switching to demure embroidery in virginal white dresses, uttering snippets of dialogue from The Exorcist and finally morphing into the disappearing girls of Picnic at Hanging Rock.

In contrast, younger artists tended to riff on themes of inheritance. Matt Prest and Clare Britton are roughly the same age as the Performance Space, meaning that they—like me—were in primary school when the Sydney Front were performing. Together with their son Leslie, they hopped into a bubble and narrated their lives from 1983, allocating each year a minute, a memory and a song.

Post (Mish Grigor, Zoe Coombes Marr, Natalie Rose) staged another of their performances of wilful ignorance, allocating themselves two minutes to select a play from the canon, two minutes to prepare some notes on a theme from a well-worn list and two minutes to link them to the plot for the audience. The results were hilarious as the performers segued from Handke’s Kaspar to Casper the movie to the actor Devon Sawa. On another night, Applespiel staged a pantomime about how they saved Performance Space and thus rescued Sydney from eternal remounts of The Summer of the Seventeenth Doll.

Themes of inheritance also arose in some of the Indigenous performances in the program. Rhonda Dixon-Grovenor appeared with her daughter Nadeena Dixon to give an account of growing up with the great activist Chicka Dixon (1928-2010) as father and grandfather. Vicki Van Hout and Thomas E Kelly duetted precisely in an hilarious dance of increasing discombobulation which definitely warrants a reprise. Other artists did not confine themselves to the half-hour time slot—Ryuchi Fujimara and Kate Sherman danced 30 duets over two days, always appearing when least expected in a variety of sites around the building.

Daydream Island, photo Zan Wimberley

courtesy & © Mike Parr

Daydream Island, photo Zan Wimberley

Mike Parr

The standout performance was perhaps Mike Parr’s Daydream Island, which took up where his performances of the early 2000s left off, returning to the subject of asylum seekers. Instead of being presented in the gallery, it was staged in a theatre with a seating bank, and instead of taking several hours, it took roughly one.

In front of a large screen upstage is a small table and a chair. Further downstage are five stools, where Parr’s assistants sit. Parr, wearing a lurid Hawaiian shirt, enters to the strains of “I Still Call Australia Home.” He sits on the chair with his back to the audience, however we still see his face, his assistant feeding the image live to the screen. A female assistant rises from her stool, goes to the table and wipes Parr’s eyebrow with iodine. She inserts a needle and thread and starts stitching. So far, so grimly familiar. But then she ties something to Parr’s face—a tiny plastic pig. The image immediately recalls the strange moment when the country was outraged about the export of live animals but silent about the outsourcing of its detention centres. Any such reading is undercut by the assortment of figurines that continues to be stitched to the artist’s cheek, neck and nose—there are animals but also superheroes.

The performance shifts when the stitching finishes and the face painting begins. Initially it is not clear what the assistant is painting—the face just looks like a lumpy mass. But it slowly resembles a Picasso and we are left to contemplate the paradox of being ‘defaced’ by portraiture. From here, Parr is helped from his chair and placed prone on the floor. His face is obliterated again, this time with Pollock paint drips. Suddenly his face becomes a tropical island and the shirt makes hideous sense. In the final moments of the performance, a plush pig toy wobbles past on wind-up wheels, nudging Parr’s sleeve on the way. One of the assistants announces that all this has been hogwash, that the dumb theatre has now come to an end, and that we can all go back to where we came from. Nearly everyone in the theatre exhales and heads for the bathroom or the bar.

Box of Birds, Tess de Quincey

photo Heidrun Löhr

Box of Birds, Tess de Quincey

New works: Box of Birds

The first week belonged to Tess de Quincey’s Box of Birds, starting in the foyer, with projections of white text (“Existence not true…”) sweeping across the grey floor. Slowly, spectators notice two figures, one on each side of the foyer, high above the audience on steel beams. They wear heavy grey felt blankets which hide their faces and restrict their movements, but perhaps also offer protection should they fall. This prospect of harm is slightly sinister, given the program states that the images are based on Anne Ferran’s photographic trilogy about female psychiatric patients in the 1940s. Soon we are enticed into Carriageworks’ corridors. Once again, we don’t always know where to look: peeking around a corner I discover a performer above me on a ladder, now noticeably birdlike in its movement. There are others. I’m no ornithologist but I think I see an ibis at one point, with a sweeping wing, and a lyrebird at another, with its long, fanned tail. In the confines of the back blocks of Carriageworks, we hear the words of Nietzsche embedded in Vic McEwan’s overarching soundwork with its cosmic and industrial resonances, birdcalls and woodwind warblings.

Back in the foyer, the felt birds are hoisted onto the beams again, scratching, teetering and nesting before coming to rest. Tess de Quincey has worked the spaces of Carriageworks perhaps more than any other artist, to the point where it’s impossible for me to observe parts of the building without sensing her performing presence. This immersive and evocative work added yet another layer to that palimpsest.

David Buckley, Nigel Kellaway, Brief Synopsis, the opera Project

photo Heidrun Löhr

David Buckley, Nigel Kellaway, Brief Synopsis, the opera Project

Brief Synopsis

The second week saw the premiere of The opera Project’s Brief Synopsis: a beautiful naked woman “of a certain age” brutally stabs a young man to death. Staged in Bay 17, the space looks as beautiful and as spare as I have seen it: the seating banks placed on an angle while the back doors are open so that we see through to the workshop. There is almost no set to speak of, only a few tables and chairs placed to the right. The performance begins with a long pause, before a car appears upstage. Several people with musical instruments get out, only to get back in. We suddenly become aware of a woman (Katia Molino), who has been sitting in the audience. She stands and walks upstage wearing a pair of high-heeled shoes and nothing else. The musicians enter again and this time they and their musical instruments stay, producing a richly textured score, oscillating between melancholy and subdued anger.

We proceed through a series of scenes that may or may not be in chronological order in which accusations are uttered at café tables between a former couple, Molino and Nigel Kellaway (the central figure and nouveau roman narrator whose nihilism and bitterness override his capacity to love). A young man (David Buckley, an impressive presence) is seduced and cruelly rejected by both. There are set pieces, as the actors and musicians stride invisible corridors, Kellaway, in black suit and silver heels, reciting arch lines about time’s inconstancy (texts borrowed from Heiner Müller, Alain Robbe-Grillet and Marguerite Yourcenar among others). There are costume changes as Molino hands her young lover a new shirt, only to reveal that it is even bloodier than the one it replaces. There are also beautiful projected noir-ish images, including webs and night roads, by Heidrun Löhr, aptly symbolic if serving too often as mere backdrops to the action. Despite the variety of material, Brief Synopsis leaves me cold, though I suspect this is precisely the point.

New Works: danse (3) sans spectacle

Staged in the same space later in the week, Rosalind Crisp’s danse (3) sans spectacle was even more stripped back and yet had a degree of warmth at its heart. We enter a dark and silent space and seat ourselves on low, grey foam blocks placed in a rough semi-circle around the three dancers. Dressed in grey hooded tracksuits and bathed in a pale yellow light, they proceed to dance—sometimes by themselves, sometimes in tandem, but rarely if ever as a trio. Even when the three are moving at the same time, one always seems to be pursuing a different logic or phrase. The phrases themselves rarely come to completion. When you expect an arm to fully extend, it folds back in on itself; when you anticipate a rolling foot to bring a knee with it, you find the knee has been diverted elsewhere. There is no music, only breath and the occasional scrape of a foot. Our attention is held solely by the dancers’ concentration, apparent isolation and occasional collaboration. The piece finishes with a lone figure, dancing far from the circle. It’s as if having done away with every other habit of dance, Crisp can now do away with the audience.

New Works: This is Barbara Cleveland

The youngest artists in this part of the program are Brown Council and, like their counterparts in 30 Ways, they appear focused on history and legacy. Their video work, This is Barbara Cleveland, is about a mythic performance artist from 1970s Sydney. The work combines footage of the four Brown Councillors speaking about the neglected artist with apparently ‘authentic’ archival footage of Cleveland herself nude, blindfolded, smeared with blood or on a ladder. There’s every trope we’ve inherited from the performance art of the 1960s and 70s, re-enacted by four different bodies who start to merge into a single mythic star. The concept is clever, the images well composed and the point well made—all performance art and artists disappear, but some disappear more often than others.

Julie-Anne Long, Directors’ Cut: Fiona Winning

photo Lucy Parakhina

Julie-Anne Long, Directors’ Cut: Fiona Winning

The Directors’ Cuts

The Directors’ Cuts proceed in reverse chronological order. First up is Daniel Brine (2008-11, and now UK-based), who did not attend in person but put in a brief appearance at the beginning of his video 30 x 30: Thirty One-Minute Manifestos for the Next Thirty Years. Some manifestos were irreverent (post), others were more earnest (My Darling Patricia), some were immersed in pop culture (Georgie Meagher) and others wanted to unplug altogether (Alison Murphy-Oates). I was won over by Field Theory’s vision of a post-ironic, futuristic, DIY aesthetic.

The following evening Fiona Winning (1999-2008) delivers a performance lecture titled Nostalgia, Chance, Accident. There are cocktails as we enter and the stage floor is covered with posters from the period in which she was director. In a typically generous gesture, Winning narrates her time at Performance Space through the artists and people she worked with, some of whom also give brief and witty speeches (Richard Manner and Brian Fuata) or performances (Martin del Amo and Julie-Anne Long). From time to time, Arts NSW’s Kim Spinks—seated in the audience—and Winning re-enact phone calls in which they drolly discuss the relative advantages of moving Performance Space to possible premises in Paddington, Newtown and eventually Redfern. The evening finishes with a standing ovation for the longest-serving director in Performance Space’s history and overseer of the challenging shift to Carriageworks.

While the planned petting zoo of Angharad Wynne-Jones’ (1994-97) Parliament of Animals did not materialise, there were plenty of dogs. On stage with pet-free Wynne-Jones and media artist r e a were Harvey with dancer Dean Walsh, Charlie with performer Jeff Stein, and Flame and Trotsky with Tess de Quincey. De Quincey talks about the difference between dancing the environment and being danced by it while r e a speaks about the significance of kangaroos to her practice and her grief at their culling. Walsh demonstrates his scuba diving practice, relating it to his ecological concerns, while Stein talks about vet bills and philosopher Giorgio Agamben. During all this, Harvey wanders back and forth, pees on the floor, distracts Charlie and bothers Trotsky and Flame, who are kept on short leash. The canine chaos is precisely the counterpoint that the conversation needs.

Barbara Campbell, Directors’ Cut: Sarah Miller

photo Lucy Parakhina

Barbara Campbell, Directors’ Cut: Sarah Miller

Like Winning, Sarah Miller (1989-93) also foregrounds the artists with whom she collaborated. She has invited a number of them to imagine a past performance or speculate on a future one. Several young men deliver texts on behalf of Malcolm Whittaker (Team MESS) while another emerging artist, Nathan Harrison (Applespiel), conjures a false memory of Canberra’s Splinters Theatre performance he didn’t see. We see Keith Gallasch and Virginia Baxter in an SBS Carpet Burns’ short video by Kriv Stenders of Open City’s The Museum of Accidents (1991) with Christa Hughes, Tony MacGregor and the works of a host of Sydney visual artists. A highlight of this session is John Baylis’ reading from his performance diary. The event he reports sounds plausible at first but slowly reveals itself to be a fiction combining almost every legend you’ve ever heard about Performance Space—a tiny audience, a shy but magnetic performer, a lighting operator asleep at the desk, 12 bridal dresses dropping from the ceiling, an invitation to the audience to put them on, a collapsing roof, a flood of rain and a cannibalistic climax. Baylis stays after the show to ask the artists if they’d like to tour the work. “Yes,” they said, “but not through space, through time.” To which he says, “I think I can help.”

The evening concludes with artist and curator Brenda L Croft speaking about the Boomalli Cooperative and its relationship with Performance Space and Sarah Miller, an important reminder that the organisation did not always soley occupy 199 Cleveland St.

Some of the Directors’ Cuts were more low-key. Zane Trow (1997-99), spoke briefly, paid tribute to Performance Space board members and delivered an hour of his sound art. Unfortunately Noëlle Janaczweska (1987-89) could not attend; instead John Baylis engaged in an informative and amusing conversation with Christopher Allen, an early Performance Space administrator working with founding director Mike Mullins. This was followed by excerpts from Clare Grant’s DVD account of the vision and works of The Sydney Front (available from Artfilms). Barbara Campbell stood in for Allan Vizents (1986-87) who passed away during his tenure as director. With Campbell, Derek Kreckler, Annette Tesoriero, Jim Denley, Sherre de Lys and Amanda Stewart performed an engaging, neatly staged selection of Vizents’ witty performance texts which satirically and sonically unpick commercial, bureaucratic and everyday idioms. In total contrast Nick Tsoutas (1984-85) threw a party, a celebration of what is to come—if trepidatious about the Abbott government—complete with live Rembetika music, octopus, ouzo and dancing.

Mike Mullins (1980-85) delivered a lecture in which he reminded us that Performance Space was “born in rebellion,” recounted battles won and lost over “new form” in the mid 80s, decried the rise of creative producers and pointed to the advantages Melbourne’s Arts House has over Performance Space because it has its own home. He declared that while Performance Space is not about a particular space it ultimately needs a designated one.

Screenings

There were also two screenings. To see the video documentation of Post-Arrivalists’ infamous 1994 performance Lock Up (in which they locked in and abandoned their audience), at first I have my head measured and shortly after my wrist cable-tied to a chair and a paper bag placed over my head. Though the footage was screened, it was impossible to see even when the paper bag was removed, thanks to the music, smoke and tasks set for the audience. In this way the group privileges the event over its evidence, the provocation over its representation.

By contrast, director and editor Karen Pearlman and producer Richard James Allen’s Physical TV documentary, …the dancer from the dance, for me lacked self-reflexivity and risked self-absorption, but much of the audience seemed to love it. The film centres on interviews with dancers about their motivations, some insightful, some not, some with all too brief glimpses of their work. Interspersed with these is footage of Pearlman and Allen across the years dancing with their children: a celebration of the family’s affection for the artform and for each other.

Television Behaviour Studies, Pia van Gelder, Tele Visions

photo Lucy Parakhina

Television Behaviour Studies, Pia van Gelder, Tele Visions

Tele Visions

You’re History! coincided with the Tele Visions festival, staged to mark the end of analogue television. On the opening night, Lara Thoms takes over one of Carriageworks Tracks together with 86-year-old Joy Hruby, who has been broadcasting her community TV show Joy’s World from her Matraville garage for more than 20 years. We are cast as the live studio audience to Joy’s last ever analogue broadcast. Thoms has done little more than place a different frame around Joy’s work—albeit an elaborate and resource-intensive one that involves a green screen deployed throughout Tele Visions—but it is done with great care and generosity and Hruby clearly enjoys the limelight. Elsewhere, Kate Blackmore and Frances Barrett were watching every single episode of The Simpsons back to back. I don’t get to see them in person but I log on to the website one morning to watch the live stream. The web cam seems to be installed just above the television, so I can hear the program but not see it. Instead I watch Blackmore napping on the couch and Barrett softly chortling. It feels intimate and intrusive, even though I have been invited.

Ending and beginning

The entire glorious event comes to a close on a Sunday night, with Dean Walsh, Stereogamous and Paul Capsis in the final 30 Ways performances. It’s been two weeks and 30 years, and time has begun to bend, stretch and recede. Just two weeks after You’re History! an email from Bec Dean lands in my inbox, advising Performance Space members that she is leaving her position as co-director to begin a doctorate. While Dean remains a curator at large, Jeff Khan is now sole director of Performance Space, which makes the memory of this festival that much more poignant. It was the end of an era and we didn’t even know it. Isn’t that always the way?

–

You’re History!, Performance Space, Sydney, 20 Nov-1 Dec, 2013

RealTime issue #119 Feb-March 2014 pg. 4-10