ghost dancing

keith gallasch: narelle benjamin, in glass, dance massive

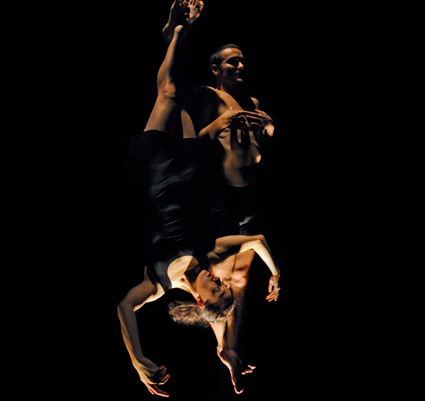

Kristina Chan, Paul White, In Glass

photo courtesy of the artist

Kristina Chan, Paul White, In Glass

THE SHEER PLENITUDE OF NARELLE BENJAMIN’S IN GLASS IS ALMOST OVERWHELMING—THE CONSTANT FLOW OF HIGHLY ARTICULATED DANCE, AN INSISTENT SOUND SCORE AND A MULTIPLICITY OF IMAGES, REFLECTED ON AND OFTEN SIMULTANEOUSLY PROJECTED ONTO THE THREE MIRROR SCREENS THAT FRAME THE PERFORMERS. I SENSE THAT SOME KIND OF ELLIPTICAL NARRATIVE IS ALSO UNFOLDING IN THIS SEMI-DARK WORLD THAT TRANSMUTES BETWEEN REVERIE AND NIGHTMARE BUT, AS WITH DREAMING, I CAN’T BE SURE. THE FOLLOWING MORNING, I WAKE TO THE SUSPICION THAT I’VE WITNESSED A GHOST STORY.

The associative nature of In Glass, where everything is half-seen through refracted light (epitomised by the recurrent image of broken glass) demands interpretation if at the same time appearing to refuse it. The work is imbued with a sense of loss, of being lost, of separation anxiety. It commences with a shadowy male figure searching with a torch and finding the body of a woman—asleep, resting, dead? Later, in a projected image, we see her run through a forest to the point of collapse and utter stillness. Later again, she will wield the torch in his absence. Back in the first scene, the female dancer appeared onscreen behind the broken glass, as if peering down at her partner’s searching: some kind of regenerative cycle, of souls together and apart, seems to be functioning.

The pattern appears to be: separation, discovery, merging, separation and re-discovery, with the everyday banality of search by torchlight offset by the mythic imagery of a tree that sprouts (the performers’) limbs, perhaps evoking the Hindu goddess Kali, at once creative and destructive. A similarly transcendant quality is found in passages that meticulously evoke Eastern temple dancing, reinforced by Huey Benjamin’s chiming score, here at its best when most delicate. The acute angularity of this deeply earthed movement and the escaping flights of finger dancing are ravishing. As so often in In Glass, the dancers are completely in synch, side by side or mirroring each other, enforcing a sense of oneness that will be lost and reclaimed over and over.

In less calculatedly transcendant passages, the moments of merging entail a range of dynamics, from swirling gyrations, one body in tow of the other in exacting floor work, to intense back-arched parallel prostrations suggestive of mutual passion and stress. At other moments, the dancers lean forehead to forehead, slide together neck across neck and glide to the floor, or elsewhere slump with alarming suddenness as if the effect of emerging is too much. At other times there is a sensual entwining, as if in sleep.

Because Paul White and Kristina Chan are dancers of inordinate finesse and skill, and because Narelle Benjamin has shaped for them a rich dance language, In Glass, moment by moment, is often deeply engaging. But that plenitude of invention becomes exacting—images race by, too fast often to find anchor in our psyches. Yes, the cycles of the work are evident as are the broader patterns of the choreography, but potentially engaging motifs are either lost or under-developed.

The notion inherent in In Glass, of having to deal with reality through refracted images of self and other, indeed “through a glass darkly,” reaches its apotheosis when White introduces two oval-shaped mirrors. He frames himself (mirrors either side of his head) with grinning mock narcissism, licking his image. He then angles the mirrors over a seated, cross-legged Chan (now costumed in gold) so that her articulation of arms and fingers transforms her into a multi-limbed goddess. However, Chan’s own reeling solo engagement with a mirror image is far less aetherial: a screen projection reveals an aged, slumped female body. It’s an unusually literal, indeed banal moment, one for which White has no obvious equivalent. When he stands alone, arms stretched out, sinuously aquiver, it’s not clear what state of being he has entered. Towards the end, when the central screen breaks in two and is angled against itself, the sense of mirroring intensifies yet again, but totally as illusion—Chan disappears. The relationship is and never was—life as ghost story.

But whose story? Although we share the points of view of both performers and each seems equally watcher and watched, there is an increasing sense that the work is focused on the man’s loss of the woman (her limp body on stage and in the forest, her transformative golden attire, her limbs dancing like Kali, the man’s greater effort in drawing him to her).

Narrative uncertainties aside, the constant multiplication of the performers’ selves on the transparent mirror-screens heightens the sense of uneasy dream. Samuel James’ images compound it: fractured glass, the dancers in various perspectives (an astonishing one, as if seen from overhead, has them sucked into a deep void), the deep green forest, a ghost tree, the sparkle of ocean waves stripped into vertical lines, two beautiful circles of fragmented light moving one counter clockwise to the other, like the dancers, together but apart. Karen Norris’ lighting adroitly sustains our view of the dancing without diluting the screen imagery, although contending with the too small performing space in the Beckett Theatre.

Although In Glass sometimes eluded me with its irritating plenitude of invention, it proved nonetheless memorable—if in the way that one struggles to recall certain dreams. The dancing is wonderful, the screen work embracing and Benjamin’s somewhat Jungian metaphysics intriguing.

–2011 Dance Massive: In Glass, choreographer Narelle Benjamin, dancers Kristina Chan, Paul White, composer Huey Benjamin, visual design Samuel James, costumes Tess Schofield, lighting Karen Norris, Beckett Theatre, Malthouse, Melbourne, March 15-20; www.dancemassive.com.au