Everything in the mix

Andrew Fuhrmann: Keir Choreographic Award Semi-Finals 1

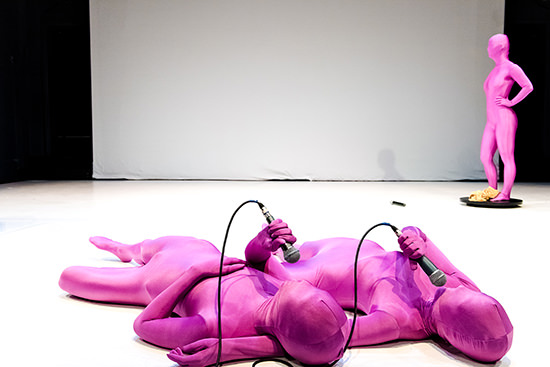

Chloe Chignell, Shine

photo Gregory Lorenzutti

Chloe Chignell, Shine

It’s no secret that the biennial Keir Choreographic Award aims to foster an expansive, cross-disciplinary vision of contemporary dance, one in which choreography is re-imagined as an associative process, a way of bringing together multiple artistic, philosophical and critical practices in performance.

This agenda may well unleash howling fantods in dance fans worried about a developing trend toward exhaustive intellectualisation; but, looking at the eight semi-finalists competing for the 2016 award, there’s no doubt that the vision has been embraced by a generation of emerging choreographers—and particularly those who trained at Melbourne’s Victorian College of the Arts.

Deep Shine

Opening the first of two semi-final programs is Chloe Chignell’s Deep Shine. Or, rather, it had been called Deep Shine. As we enter the space, we find a figure, all in gold, standing on a motorised lazy susan, stage left, cordless microphone in hand, repeating in an icy monotone that the work has been retitled. It is now called ‘Shine’. Depth, it is implied, is no longer interesting. The surface and its glamour is all.

Sheathed in Spandex bodysuits, elasticised fabric covering hands, feet and faces, the three performers are like personifications of pure gloss. One body, all in magenta, lies on its side against the back wall of the space. Another, also in magenta, stands on a downstage plinth. Which one is Ellen Davies and which is Bhenji Ra? We know that the figure with the microphone is Chloe Chignell because she tells us so. But, on reflection, can we be sure?

The work suggests a kind of generalised anxiety around the labour of identity construction, a paradoxical need both for self-exposure and also self-preservation. In one memorable scene, Chignell removes herself from an orgiastic tangle of shiny bodies, returns to the spinning dais and strips off her jumpsuit, revealing yet another jumpsuit. One skin is sloughed off to reveal another. We imagine that the figure is nothing but jumpsuits all the way down.

Sarah Aiken, Sarah Aiken (Tools for Personal Expansion)

photo Gregory Lorenzutti

Sarah Aiken, Sarah Aiken (Tools for Personal Expansion)

Sarah Aiken (Tools for Personal Expansion)

Sarah Aiken explores a similar complex of ideas in her piece, Sarah Aiken (Tools for Personal Expansion). As in Chignell’s work, the dance begins with the choreographer speaking her name into a microphone. Claire Leske and Emily Robinson then enter the space and each repeat the same name—Sarah Aiken. Aiken then slowly paces out the width of the stage, moving back and forth with Leske and Robinson in her wake performing in canon.

In the middle section, the dancers use the panorama function on an iPhone camera, live streamed to a large screen at the back of the stage, to digitally manipulate an image of Aiken’s body in real time, making it appear as if her arms and legs stretch around the entire room.

There are echoes here of Atlanta Eke’s Body of Work, which won the inaugural Keir Award in 2014, but Aiken is undoubtedly on her own investigative trajectory. Perhaps the most interesting thing about Sarah Aiken (Tools for Personal Expansion) is the surprising way that it builds on her previous work, SET, which was part of the Dancehouse Housemate program in 2015 and which also explored ideas of bodily extension and video manipulation. The final scene of her Keir entry, in which she advances toward the audience with her arms open wide, extended with the help of trick sleeves, seems a particularly clever re-imaging of the closing moments of SET.

Martin Hansen, if it’s all in my veins

photo Gregory Lorenzutti

Martin Hansen, if it’s all in my veins

If It’s All in My Veins

Martin Hansen’s if it’s all in my veins is a much darker and more overtly physical work, one which seems to suggest that the history of dance—and its future—is little more than the endless reproduction of fundamentally empty appearances.

A laptop sits onstage with a clock counting down on its screen. Performers Hellen Sky, Maxine Palmerson and Michelle Ferris busy themselves aiming mobile spotlights and arranging fluorescent tubes. When the clock hits zero, an animated GIF appears on a screen at the back of the stage showing an iconic dancer—a Nijinsky or a Pina Bausch, say—captured in a rapid loop. The three performers then throw themselves into a rough imitation—not of the dancer, as such, but of the representation of the dancer, with all its glitches and distortions.

The work has a bit of a scrapbook feel, with a lot of different ideas stuck around the central theme of imitation and simulation. And to a greater or lesser degree this same scrappiness is a feature of each of the first four works created for the Keir Award this year. Perhaps there was some pressure on the artists to cram full their entire allotment of 20 minutes, but I think in several of the works a shorter, less fragmented, more focused presentation might have had more impact.

Alice Heyward, Before the Fact

photo Gregory Lorenzutti

Alice Heyward, Before the Fact

Before the Fact

The final work on the first night’s program is Alice Heyward’s Before the Fact. Heyward has invited artist Ilya Milstein to illustrate a book of imaginary dance notations, which she here interprets for us as a kind of performed sketch. Slowly and carefully, she walks across the stage, folding at the hips, crouching, partially extending her arms, all while reciting a manifesto-like statement on her archive of a future choreography.

The work does have the feel of something that has been unpacked for the first time, like something that has just arrived from the future. Matthew Adey’s set design even includes drifts of bubble wrap, piles of loose cloth and plenty of packing tape. And it all has some incipient interest, but Heyward doesn’t quite manage to suggest the full choreographic potential of the fragmentary moments inspired by Milstein’s drawings.

Keir Choreographic Award Semi-Finals, Program One; Dancehouse, Melbourne, 26-30 April

Next week in RealTime: Andrew Fuhrmann reviews Semi-Finals, Program Two, and we’ll report on the Finals, playing this week at Carriageworks, Sydney, 5-7 May.

RealTime issue #132 April-May 2016