displacements: space, stage, workplace

keith gallasch: branch nebula’s sweat & other works

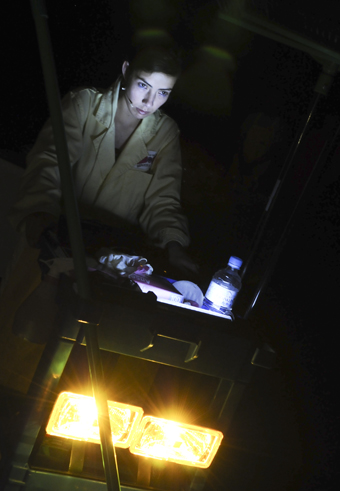

Claudia Escobar, Sweat, Branch Nebula

photo Heidrun Löhr

Claudia Escobar, Sweat, Branch Nebula

BRANCH NEBULA’S SWEAT WITTILY AND FORCEFULLY DISORIENTS OUR SENSE OF WHAT IT MEANS TO BE AN AUDIENCE. IT THEREBY COMPELS US TO REFLECT ON OUR RELATIONSHIP WITH MIGRANT SERVICE INDUSTRY WORKERS. THE PERFORMERS, FROM A VARIETY OF CULTURAL BACKGROUNDS, INVITE US INTO THE EMPTY MAIN HALL OF NORTH MELBOURNE TOWN HALL. WE CROWD IN, RECEIVE INSTRUCTIONS AS TO HOW WE SHOULD BEHAVE—AUDIENCE WORK—AS WE WITNESS THE PERFORMERS AT WORK, CONSTRUCTING A PERFORMANCE—WHILE THEY, IN TURN, WORK US.

Some performers demonstrate their mundane tasks (enacted both literally or danced abstractly) as they move amongst us and the dangers of infection are recited. One man approaches us with a stack of white dinner plates, spreads them at our feet and re-stacks them with clattering musical verve. He joins other workers setting out a long table for a banquet at the other end of the hall and, from a distance, expertly spins the plates to a waiting fellow worker who briskly sets them. Other banal tasks, like handling glasses are made artful—rolled in small arcs—or spoons picked up, rattled like a tambourine; work made art, defeating boredom.

As one, the performer-workers rapidly build the space that we are to inhabit with them—we are within their design. The emptiness is filled with a chunky sound system, speakers and a variety of light sources, all wheeled on briskly, pushing through the audience. Intense pockets of light and the visceral rumble and fine higher textures of Hirofumi Uchino’s live sound compositions permeate the space, edging the idea of work into displays of very different skills: dance, sound, song, martial arts and football—activities that appear to express the workers’ after-work actual being. These are imbued with an air of fantasy, of release, of brief moments of interplay, mutuality and even threat—how far can you go when you aim a football kick at a fellow performer standing perfectly still against a wall? This turns into a perverse kind of dance with the female ‘target’—legs and body arched—transmuted into a human goal. At work, perhaps one can dream. Or not—a woman cleans the floor obsessively with her hair. Another worker inhabits a garbage bag. Another is dragged about. The workplace is a mire of desire and nightmare.

The action of Sweat is spread around the space, pulling us to it, or we’re directed to make a choice, to fix on one of four performances. The work will soon focus on the banquet table and we’ll crowd around it. That defiant ritual over, the performers open out the space, filling it with unregulated energy before exiting.

the audience inside

Much contemporary performance and dance, and some cutting edge theatre, is preoccupied with disorienting audiences, and with a sense of purpose that is not merely experiential. Unusual seating configurations and moving audiences about during performances are a familiar part of the repertoire and subject to repetition and clever reinvention. What has grown more recently is a greater desire to place audiences inside the work. This parallels and borrows from visual art installations, interactive media arts, the return of 3D film and the proliferation of Live Art creations that heighten some senses by depriving us of others. In the latter case, the senses themselves are often the subject of the work.

However, this heightening of audience subjectivity relies in the first instance much more on spatial arrangements than on pervasive sound design (a fusion of cinema and sound art), innovations in lighting and the immersive attractions of the screen (nowadays such a frequent component of live performance). That said, this is a two-way process: Melbourne’s Ben Cobham and Bluebottle design with light; multiple-channel sound design places audiences inside virtual worlds; and screens can challenge our sense of perspective and conjure illusory spaces. Even so, light, sound and projections have to be housed and framed before they can trigger the desired experience.

making room for the senses

Increasingly design for the performing arts has to accommodate these experiential potentials. In Narelle Benjamin’s In Glass, within a darkened space mirrors doubling as screens for video projections are also transparent or, when not, can be used for shadow play. The two dancers are constantly multiplied, merged and disappeared, paralleling the mutating state of their relationship and the mirroring inherent in the choreography. It’s the simple (but doubtless complexly negotiated) positioning of the mirror-screens that frames the action, and holds the images. and the lighting of the dancers cannot afford to mess with the projections and reflections of this reverie into which we peer. There’s a lot of peering these days.

For Michelle Heaven’s Disagreeable Object, Ben Cobham and Bluebottle have constructed a transportable, small, narrow black box that can provide the tight sight lines needed to pull off surprising visual effects that in matching the performers’ movement realise the silent movie-cum-gothic horror ethos of the work while adding a more contemporary, eerie and finally spectacular depth of field. Cobham and collaborators, not least in their work with Helen Herbertson, are always adroit at disturbing our field of vision, flattening dimensions and creating evanescent fields of colour (like the floor washes on which Jenny Kemp’s Madeleine seemed to nightmarishly float).

interior designs

For a work as delightfully unstable as Luke George’s exercise in immediacy, NOW NOW NOW, there was also a great sense of fixity about Benjamin Cisterne’s impressive design—interior design no less, for a starkly stylish home, or a fashion store (a sense compounded by the eccentrically costumed opening display and odd posturing and strutting). We leave our shoes in the foyer and enter a space entirely walled with black drapes; floor and seating are uniformly covered in white felt; and the ceiling is adorned with four large panels of textured, white Japanese paper covered lights hanging over us and the performance space. We are well lit as the performers. We are one. We are at home: the tension between certainty and potential chaos kept in fine check. Real life on another plane.

Harriet Ritchie, Stephanie Lake, Marnie Palomares, Alisdair Macindoe, Joseph Simon, Connected, Chunky Move

photo Jeff Busby

Harriet Ritchie, Stephanie Lake, Marnie Palomares, Alisdair Macindoe, Joseph Simon, Connected, Chunky Move

immersions and installations

Dancers occupy, shape and generate space. In Chunky Move’s Glow and Mortal Engine this was made more palpable—Frieder Weiss’ interactive video projections allowed the dancers to literally illustrate the spaces they made. They broke up grid lines, churned out curves and left behind impressions of their presence. A move could trigger a rush of insect-like animations that filled the floor-screen space and was suggestive of the power that radiates out from the dancing body.

In Glow the audience, seated in a rectangular frame, looked steeply down on the solo dancer as she moved against the floor-screen. The effect was, not surprisingly, both vertiginous and immersive, with connotations of laboratory or museum. In Mortal Engine, performed in traditional theatre spaces, the floor-screen was wide, accommodating more dancers, but tilted even to the vertical, so that again we felt we were looking into a highly active specimen case, as its dancer-creatures crawled over its edges and crawled, glided and tumbled across the surface. In both works the effort to disorient the audience is inherent.

In Chunky Move’s latest work, Connected, choreographer Gideon Obarzanek pursues some of the cause and effect patterning of Glow and Mortal Engine but with physical materials rather than virtual ones. Instead of the digital sculpting of images by computer artist and dancers, here it’s the interplay between dancers and a huge kinetic sculpture made of paper, string and timber that is central to the work. The stage space is conventional, but the scale of Reuben Margolin’s kinetic sculpture, already lit as we enter, makes the work unavoidable. As I wrote in my review, “If we weren’t seated we could be in an art gallery.” That tension, between theatre and gallery, is played out, even made literal, in the course of Connected. It’s a reminder too of the influence of the visual art installation in a wide range of performance works and dance, strikingly in Lucy Guerin’s Structure and Sadness.

use me

As dance and contemporary performance continue their long, hybridising engagement with other artforms, the elements that create aural and physical space (projections, sound, light, interactives, animatronics, architectural and design sensibilities) loom large. Apparently inanimate or virtual (if always artist creations) they assume stage lives and realities of their own (recall the music and light entractes in Mortal Engine), ones which we increasingly inhabit with the performers, walking through the fourth wall to join them, or imagining we do due to a trick of light or sound. Sometimes it’s so simple. Of Rosalind Crisp’s No one will tell us…I wrote about “the exploitation of the theatre’s spaces via the distribution of movement and the excellent lighting [with] a life of its own. At times the guitarist is foregrounded, Crisp in the dim distance, insisting on another perspective on the dance; at others the light establishes a space, as if to say, use me.”

–

Dance Massive: Branch Nebula, Sweat, co-creators: Lee Wilson, Mirabelle Wouters, performers, devisors, choreographers Claudia Escobar, Erwin Fenis, Ali Kadhim, Ahilan Ratnamohan, Angela Goh, noisician/live sound Hirofumi Uchino, dramaturg John Baylis; Arts House, North Melbourne Town Hall, March 18,19; www.dancemassive.com.au