dancing into identity

melissa quek: idf emerging choreographers program

5,6,7,8

photo Phalla San

5,6,7,8

WHAT? WHY? HOW? THE EMPTY STAGE IS A BLANK SLATE WHERE FIVE YOUNG INDONESIAN CHOREOGRAPHERS (FROM ART UNIVERSITIES AROUND INDONESIA: THE JAKARTA ARTS INSTITUTE (IKJ), ISI YOGYAKARTA AND UNESA IN SURABAYA) MAKE THEIR MARK. AMIDST MUSICAL CACOPHONY AND THE BLUR OF LIGHTS, LIKE ANYONE IN THE EARLY STAGES OF DEVELOPMENT THESE EMERGING ARTISTS SEE PATTERNS, QUESTION STEREOTYPES AND TRY TO FORGE IDENTITIES.

5,6,7,8

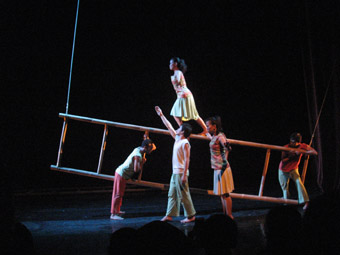

In the language of the dance world 5,6,7,8 means prepare. And you should, when a cycle of beginnings commences the moment the lights reveal two men bursting into explosive kicks and jumps to the creaking sound of straining wires. A ladder, over which the men move quickly and deftly, lies inertly on the floor beneath their feet.

In Nur Sekreningsih’s 5,6,7,8, sound loops shift from the resonances of traditional instruments to running notes on the piano to concrete sounds and back again. This musical history is mimicked by the dance movements, rotating between traditional, contemporary and folk, a formal construction that underpins the work’s theme: the cycles in relationships.

The dancers cover the space well with energetic leaps, conveying a strong sense of motion and interaction. Set higher and higher—on its side, sloping, suspended above the shoulders—the bamboo ladder allows varying forms of engagement and framing but is also a hindrance. The dancers are entertaining when they jump through the rungs or hang from the ladder’s uprights but, unfortunately, the increasingly precarious ‘tightrope’ act, performed at each level of the ladder’s positioning, misses the mark. The spectacle of the balancing act as the performer teeters on the edge of the ladder detracts from the image of the dancer as forward-looking—she is more tentative than progressive. Nor is it clear how this image of isolation relates to the cyclical nature of relationships.

Cekrek

photo Phalla San

Cekrek

cekrek

Exploring how family dynamics can affect identity, Cekrek is the poignant and humorous highlight of the showcase. Choreographer Joko Sudibyo’s choreography is an expert fusing of styles in which the wide stance, flexed feet and soft arms of Balinese dance combine with a jazzy influence evident in undulating bodies and quick rebounds off the floor. The all male cast confidently perform the steps, exuding a youthful precociousness that makes me smile.

Posing for imaginary portraits, four youths, neatly dressed in short sleeved, white collared shirts and brown trousers—a typical school uniform—freeze each time the lights flash. They are oblivious to the mother figure kneeling directly in front of them, her back to the audience displaying perfectly coiffed hair pulled back in a low bun and the blue lace of a Kebaya (blouse).

This woman rises gently and moves off-stage, the performer’s masculinity barely discernable, so delicate and poised are his movements. The eyes of the boys are glued to her as she exits but her absence releases them into a series of body waves—head, chest, belly, hips, lifted in successive sequences. They horse around, pushing and gesturing, isolated heads moving quickly from side to side, pointing (mostly with the middle finger), jabbing and thrusting, painting the air around them—their movements still suggestive of traditional dance. The boys appear to revel in their independence.

Is the bare-chested dancer who enters next a memory of an absent male authority figure? The four crouch around him as his back and extended arms move in sinuous ripples, as if jolts of electricity run through his veins. The ‘mother’ returns to the stage, and he dances with her in a strange duet, the relationship appearing to be that of human and ghost. He navigates the space around her, never making contact as she, seemingly unaware of his presence, makes her slow progress across the stage to exit. Then he too disappears.

Another female character enters, also a male dancer, this time with long wild hair, a pink tank top—showing off chorded muscles—and a traditional long cotton skirt tightly wrapped around the legs. This woman is a caricature, like a soap-opera mother. Unlike her silent counterpart, she wails melodramatically, stops abruptly turns to the audience, says she’s been “crying for three days” then resumes her squawking, half-dancing, half-sobbing around the stage.

Trying to shame the boys into reaction, this single mother (the program note explains that the woman is the family’s breadwinner) pulls her hair into a mad tangle, tossing and flicking it every which way, shouting in Bahasa that she deplores their ingratitude, for never thinking about her or the family. She yanks their heads back as she scolds and cajoles, but they ignore her, remaining inert, eyes closed. Later they gather behind her as she continues to jabber, pointing and gesticulating; naughty children mimicking a scolding parent.

Somehow order is restored when the genteel Kebaya-clad mother returns: the boys shuffle away, straighten their clothes and line up with the wild-haired mother. Suddenly, the genteel mother whips out a camera. Pasting on cheesy grins, cranky mother and sons pose for a portrait—the illusion of a happy family.

Gayaku

photo Phalla San

Gayaku

gayaku

This night’s program seems to be a re-contextualising of traditional Indonesian dance forms within a modern framework. Nowhere is this theme as clear as in GAYaku which starts quite traditionally—a man sits cross-legged, meditating on a shoulder high table under which people sit like ancient sculptures. From the edge of the stage traditional musicians play a haunting gamelan melody and chant in eerie unison. The dancers move through the strong poses characteristic of males in Javanese dance.

Part-way through, round gold, helmet-like hats with a protrusion on the crown are worn, then playfully cupped against chests, thrown in the air and turned upside down like bowls—Freudian symbolism perhaps of dual sexuality. Exploring the freedom of new gender identity, the male dancers perform traditional Javanese female movements; using soft fingers, vainly admiring imagined reflections, taking tiny, demure steps, they move the work to its campy ending.

To reach this freedom there must first be a moment of crisis. In the program note, female choreographer Shinta Maulita, writes, “I try to love the person I am supposed to love…but I can’t.” This might indicate that GAYaku is about Maulita’s frustrations, but it’s about much more. In a pair of duets, a male dancer partners Maulita. As they face each other, legs wide apart and hands outstretched, this traditional Javanese dance movement becomes the basis of missed kisses as the dancers’ faces bob and weave. The key image is of Maulita cradled, like a bride about to be carried over the threshhold. Lips almost meet but her partner’s eyes shift away, an expression of anguish and regret on his face. A male-male duet ensues, the dancers circling each other, legs moving closer but bodies stretching away in hesitation. In the end they embrace, faces frozen inches away from a kiss. Maulita’s work has brought the audience to the brink of a transition but by not taking the final step she keeps the work in the realm of pretense, and leaves the rest to the imagination.

In GAYaku, traditional movement becomes sexually charged: a basic shoulder roll, usually delivered slowly and with care, becomes a seductive shimmy; the wide legged walk with gentle hip sway turns into a booty shake as the dancers gyrate to the rhythm of the music. Finally, moving among the audience they blatantly flirt and tease, questioning and inviting.

Retorika Kerinduan

photo Phalla San

Retorika Kerinduan

retorika kerinduan

Retorika Kerinduan is Santi Pratiwi’s discourse on increasing urbanization and the inability to assuage a longing for the old village life. A body is lit in the centre of the stage, no head or legs, just a back, naked but for streaks of metallic gold paint, pushing and heaving to ominous grating sounds. It is a man struggling to rise; distorted arms pushing outwards, he appears to be hatching from an egg. From deep in his throat come strangled sounds as he gasps for air. Kneeling in a semi circle, three women slowly bow their heads to the ground and, returning to the upright position, ritualistically repeat the movement. Perhaps the choreographer suggests that the worship of money is suffocating.

Near the middle of the work an image of human devolution appears. Almost as a footnote to a series of martial arts inspired, middling lunges and quick jabs, three dancers enter at varying heights, ranging from upright Homo Erectus to crouching monkey. The final image is of a silver robed figure with a cardboard box—shaped to represent a sky-scraper—on his head, a woman at his feet. Behind him the trio of women move as if in a funeral procession, dropping brittle brown leaves, mourning encroaching urbanisation.

bunglon

The final work, Bunglon (Chameleon), is an oblique criticism of the hypocrisy and Machiavellian attitudes of opportunists in politics and entertainment expressed through a mashing of cultures. The dancers are adorned with feathery headpieces and similar arm-bands. In a nod to hip-hop couture they hike up one pant leg and near the end of the work add a sneaker, while painted flames—vibrant tribal-like tattoos—lick up the sides of their exposed calves. Serraimere Boogie Yasson Koirewoa’s choreography is a reflection of this blending—hip-hop grooved traditional dance gestures. The images are not particularly symbolic but the permutations of movement formations suggest the easy adaptability of a reptilian species.

The movement language of the works in this program may not have been particularly original and I’m bemused by the overabundance of images and occasional mixed metaphors. Most of the pieces rambled in their search for cultural and individual identity, but this is a forgivable short-fall in the work of young choreographers. They were well served by a high level of physicality and commitment from all the dancers. These choreographers are off to a good start in defining their styles. Perhaps I was impatient only because youthful confusion is catching.