Dance actual and virtual

Eleanor Brickhill and Sue-ellen Kohler discuss Company in Space’s The Pool is Damned: Trial by Video and Garry Stewart’s Helmet

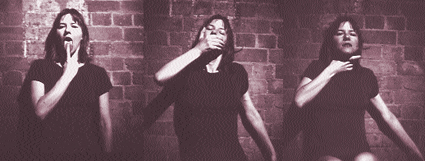

John McCormick, Company in Space’s The Pool is Damned

Early aspirations of Company in Space for this venture included not only simultaneous interactive transmission to Sydney, Perth and Brisbane of The Pool is Dammed: Trial by Video—staged live this month in Banana Alley Vault 10, Flinders Street, Melbourne—but also the performers working from each of these scattered places. Using time variations between cities, there might have been a kind of piggy-backing of performers flying around the country, simultaneously creating a nationwide net of live activity and simulacra. Logistically a nightmare, of course, but if big ideas don’t always come off, the effort to realise them can produce brilliance.

The permutations of Pauline Hanson’s maiden speech shaping national consciousness have become the stuff performers dream of, rendering visible the issues of belief and truth and how they operate within the media’s shifting parameters. I anticipated something special, as I sat ready to watch the Sydney performance, waving briefly to Lucy Guerin as she put her lipstick on in Melbourne. The performance began there, for me, without any sense of a division of boundaries, because I had anticipated that somehow ‘interactive’ augured a different kind of involvement.

Two screens: one vertical and one across the floor which was strewn with sand. The sandpit attracted any child within crawling distance. A video camera on the ceiling squashed children and other patrons’ wandering images flat against the vertical screen, somewhat scrambled and delayed. The vertical screen menu directed that movement across the sand would activate sound events in Melbourne, and you could also acquire other information, such as titles and participants’ names.

Mentally picking my way through the technology, I caught on that the work was divided into sections: Speech (a solo by Trevor Patrick), Dissent (Hellen Sky), Translation (John McCormick), Diplomacy (duet, John McCormick and Trevor Patrick) and Trial (Lucy Guerin). Each dancer had originally developed a kind of character using their own gestural vocabulary, and this gesture was then treated and transformed into the images we saw. The sound collage was a portentously shredded and rebuilt version of Pauline Hanson’s maiden parliamentary speech, also partly manipulated by the audience at selected moments of interaction. But Andrew Morrish’s character of the Orator provided a mostly untreated voice-over explanation of events.

EB Sue-ellen, you saw the original live Melbourne performance as well as the Sydney transmission. How do they compare?

SEK Rather than in those rough-hewn vaults in the Economiser Building, the video performance was staged in an old tunnel underneath Flinders Street Station. It really seemed to make the ideas clearer, having the bodies positioned there with the technology. The impact was so much richer, and the issues seemed much closer, more felt. The highlights for me were definitely Trevor Patrick and Lucy Guerin’s solos. But you missed so much of what Trevor was doing when you only saw the video. I couldn’t even get a sense of it.

EB Yes, that ominous pointing, like some angel of death, it seemed so epic, but you weren’t quite sure why. I guess the subtitle is apt, Gesture, Race and Culture on Trial. What people make of gesture, although it may not be related to the truth, becomes the truth.

SEK Well, you understood why in the live performance. The live bodies spoke so much more eloquently than the technology alone. Especially during Trevor’s solo, you could hear words from Pauline Hanson’s speech, not the actual speech, but a distorted version. He stood on a pedestal. Above and in front was his huge, silver glowing distorted image. But you also saw Trevor, the person, a live, normal, cool body, and you realised just how unlike him the distortion was, even though people might still say that’s him. And not just the performers, but the subject matter itself is totally mediated by the technology. When you see both together, there’s the possibility of a different level of understanding.

EB Believing what you see and hear. I loved the oration, Andrew Morrish talking about teflon suits, persuasive speakers, how we need to believe: “I believed everything that was written…I believed that Spot could run”. Our capacity to learn and understand language and gesture depends on a capacity to believe that what we hear and see is true.

SEK In Trevor’s dance, with his live presence, the video screen, and the distorted sound, you get confused as to where the authority is coming from. Then you see it’s about manipulation, all those Hitlerish gestures. Manipulation by the media, and by politicians. There seemed no freedom, no freedom of speech.

EB I found the interactivity disappointing. I think it was more fun for the technicians running around and setting it up. In the end there wasn’t much to do. I was all prepared to get up there and jump around, but all you could do was play with the sound. I was hoping for a different kind of interactivity, enough so maybe you could talk to dancers while they were actually performing. One’s imagination sets impossible tasks.

What was Hellen Sky doing in the section called Dissent? It was hard to know what sections were about if you didn’t read the program. I remember she was wearing pearls, and I remembered Pauline Hanson’s photograph. And once again, those epic gestures had to mean something, but what?

SEK I didn’t really get a sense of what the performers were doing through the video, but I remember that sense of distortion. For instance, with the sound, all those words from Hanson’s speech, some like ‘multicultural’ stood out. They took on a new kind of currency.

EB The distortion and complexity becomes the point, doesn’t it? I don’t think most people know what was actually in Pauline Hanson’s speech, or what she meant by it. But there’s been so much talk, everyone thinks they do know (Frontline recently demonstrated that really well). People interpret speech and gesture in ways that make them happiest.

Lucy Guerin, Company in Space’s The Pool is Damned

SEK And Lucy’s solo, in the Melbourne version, was emotionally so strong. She made me feel that the effort to communicate, with those anguished gestures, seemed doomed to fail. We were all on trial.

EB In the video, it was hard to see what she was actually doing. I guess that’s the point too. Like Chinese whispers, you remember the clearest gestures best—like the slash across the throat, the red dress. That’s a distortion of the message. People had to sweep the sand from the screen to see her.

And maybe the fact that it’s A Trial by Video means that we miss a lot of the detail of what’s really going on. When witnesses speak via video in court, it’s because they are fragile or vulnerable for some reason, like young children. It’s easier for a child to cope in a court when they don’t have to experience all the frightening detail of the flesh. At the same time, that’s a distortion of the real message, without all its emotional nuances. News clips about current events are generally all the information people get. You know it’s tampered with, and yet you have no option but to accept it as genuine information, at some level.

And what about the body in Garry Stewart’s Helmet?

SEK It wasn’t a brilliant piece, but it was more than ‘arm and leg dancing’, to coin a phrase. I think it made sense in the context of Foucault, the medicalisation of the western body—showing freaks, bodies pushed to extremes, and our cultural obsession with that. In the context of all those elements, the way it was designed, the mixed media, the costumes, I could enjoy watching the movement, and for once, dance that’s extreme, hard and fast and pushing bodies to a level that ordinary bodies never even dream about, it actually made sense.

EB I wondered how purposeful Garry was in using that western modern ballet material, and those extreme physical states the dancers needed to go to, to perform his particular choreography. Justifying that by using yoga to demonstrate just another kind of ‘freakish’ physical state one can aspire to, seemed thin to me. I don’t feel he took the philosophical implications of any of that material into account.

SEK I think he made a real effort to stand outside the language, to comment on our culture’s need for those extremes, pushing the excitement boundaries, and I like that, but I suspect that he really does love the physicality more than the discussion of it, even though he couches his desires in that questioning kind of way. I could appreciate Craig Proctor’s yoga demonstration (I hate it when yoga is called ‘contortions’), but it bothered me slightly that the context Garry offered gave it no meaning other than contortion, extremity and abuse.

But I don’t know whether he had complete control over everything. When you’re about to perform, a lot of things happen that you’re not really author of. So, maybe it was a happy mixture of many people’s input.

EB Perhaps it was accidentally interesting?

SEK It doesn’t matter whether it’s accidental or not. The issues raised are worth thinking about.

–

The Pool is Dammed: A Trial by Video—Gesture, Race and Culture on Trial, Company in Space. Conceived by John McCormick; score, Garth Paine; lighting, Greg Dyson; cameras/photography, Gary Sheperd, Oliver Uan Qiu Wang; computer graphics:, Luban White. On-line from Melbourne to PICA, Perth; Experimetro, Brisbane; and The Performance Space, Sydney, March 4-15

Helmet, choreography by Garry Stewart, designed by Brett Chamberlain, Daniel Tobin, The Performance Space, February 3-14 1997

RealTime issue #18 April-May 1997 pg. 35