Cutting through the fog

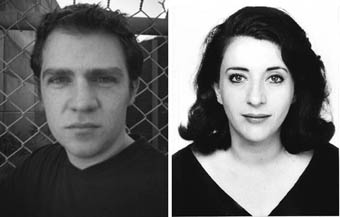

Keith Gallasch talks with Ben Ellis and Louise Fox

Ben Ellis, Louise Fox

The Sydney Theatre Company’s busy and highly productive Blueprints Literary program is run by Nick Marchand, Artistic Development Manager, and, until recently, Artistic Associate Stephen Armstrong who has left Sydney for Melbourne.

Overall, the Blueprints program adroitly combines development and production, offering playwrights very practical assistance and staging some of the most interesting and challenging work from the STC in recent years, as directed by Wesley Enoch and Benedict Andrews. Benjamin Winspear (a fine performer: Kate Champion’s Same, same But Different; Max Lyandvert’s production of Richard Foreman’s My Head is a Sledgehammer) has taken over the resident directorship, staging 2 plays in 2003 that are emerging from the writers’ program: Ben Ellis’ These People and Brendan Cowell’s Morph.

The literary program of Blueprints comprises professional development for an invited “assembly” of 5 playwrights, bi-monthly rehearsed playreadings (including in 2002 a rare opportunity to experience recent German playwriting) and public forums (The Advance Party). Other writers in the assembly are Vanessa Bate, Emma Vuletic and Marchand himself, all working on the development of full-length plays with dramaturgs Beatrix Christian, Louise Fox and Jane Fitzgerald and mentors David Berthold (the newly appointed AD at Griffin), Verity Laughton, Marion Potts, John Romeril and, until recently, Nick Enright (whose recent death is sadly lamented). The program also includes short-term ‘responsive projects’ allowing writers to work experimentally with actors, directors and dramaturgs on smaller projects. That’s where this discussion with playwright Ben Ellis (whose Falling Petals opens shortly at Melbourne’s Playbox) and dramaturg Louise Fox (a film and television writer remembered as a striking performer in Barrie Kosky’s Gilgul Theatre).

Ben Ellis The Responser project I did as part of the Writers’ Assembly in 2002, where each of the writers took on an 8 week time-frame, picked an article and used it as source for a half hour presentation. Mine was based on the transcripts of the Senate Enquiry into ‘the children overboard affair.’ It involved a workshop with actors, a really rewarding process, both for verbatim and imagined responses to the text but also in having to work outside the box. The “fog of war” was really interesting. Admiral Shackleton more or less accidentally said that there hadn’t been anyone thrown overboard and in an attempt by the Navy to get themselves out of a problem he read out an amazing statement that read like a postmodern poem about how things come together and create a fact and then they disperse…a kind of mist of Naval language.

These People is another project, originally inspired by peoples’ experience of detention centres in Australia—they’re actually called “Immigration, Reception and Processing” centres. ACM have advertised positions for detention centres even though legally they’re not to call them that. I gathered interviews with people who’d worked in the centres but we didn’t want the focus to be on them and Ben [Winspear] and I had talked about how it couldn’t be just a verbatim piece as told by refugees…there were certain problems of reception of voice, of attitude, which you can solve with say a play like Aftershocks [about the Newcastle earthquake]—not that that’s an easy piece…

KG Well, there are some cultural variables there too.

BE …[So] we realised we’d have to investigate those variables in the process. After a while I decided it had to be about the Australian response to the refugee story, which is a story older than the Bible…We have to see what’s changed, what’s the rupture—it’s a change in the Australian mindset to asylum seekers by boat…something has shifted and we had to investigate that.

KG It was something bigger, not just a matter of falling for government rhetoric?

BEYes, something bigger and how that was interfacing with that government rhetoric. At the same time there was a Human Rights enquiry into the effect of detention on children which brings up a lot of horrific details.

KG You assimilated this over….?

BE About 2 -3 months before going into a 2-week November workshop last year.

Louise Fox I’d read a lot of the material Ben had sent us and I was there for the 2 weeks and then, when we came back together, the play formed. When we started off we were just throwing all kinds of exercises at the material. The concept of the play genuinely grew out of the workshop.

BE And we did a lot of exercises dealing with attitude, taking bits of language and speaking in different ways, working with archetypes.

KG How did you break from documentary to fiction?

BE I think that’s what it’s about when, as a body politic, we’re encountering a refugee, it’s someone we’re imagining. The first project, Select Committee For Imagining a Certain Maritime Incident: A Progress Report, looked at a recurring nightmare of the threat of cultural and geographic invasion. The words that kept coming up were completely related to the imagination, the subconscious if you like—not just the fact, but the dreaming of the fact and how those 2 interrelate. If you look at Philip Ruddock’s language it’s devoid of specific details, and he’s a master of that, [creating space] for people to imagine that refugees are hitting and cutting themselves for a good outcome…

KG Was the imagining theme there when you came in?

LF Not as concretely as it became. What we noticed was that we had a ‘family’ in the room, with 2 older and 2 younger actors, a family in an odd space confronted with this odd information. Once we’d said they look like a family, Ben went away and then came back with characters, in many ways Australian archetypes but with very specific details about them. Ben’s plugging into a history of anxiety—half of the material is [documentary], half is generated from these characters who pretty much speak in third person, so there’s a level of dissonance in the way they deal with themselves.

It’s about making you listen because we’re so assaulted with mediaspeak and it’s very easy not to actually hear. The moment you shift an attitude you begin to hear…There’s not a single moment in the play where you hear a piece of information from the person you’d expect to hear it from…so it’s constantly trying to shift your ear.

KG Australian political writing is not good at language analysis, though Guy Rundle’s Quarterly Essay on John Howard is an exception.

LF I think that’s where Ben is gifted. The play feels as politically sophisticated as it is theatrically.

BE I think the area itself [the ‘refugee play’] is a place where normal storytelling or story as function has all of sudden failed, because every person who wants to tell their story thinks it will deliver the final word and the release—from having it listened to and accepted.

LF It doesn’t happen.

BE The audience have to listen. They have to make a story themselves, in terms of their own lives in response to the show.

LF It’s in the title of the play, These People…indeterminate and exclusive.

KG What was your dramaturgical role?

LF There wasn’t a script initially, so I’m here to help Ben and everyone make the best piece of theatre they can. It was about provoking Ben and finding links for him all the time…

KG …moving towards a script? Worked on by a group but not group-devised, still writer-centred?

LF With the theatre as another tool.

BE You need as a playwright, at some stage, to get in contact with the idea that it’s actually a craft, with bodies in time and space and that’s what it’s about. You can, if you’re a developing playwright, be left in a room with no idea what an actor does, or what you need or what kinds of things might spark you off.

KG This oscillation between the aloneness of writing and the togetherness with the creative team, do you enjoy it?

BE I like it when it’s very compressed—it’s a conversation between those 2 states…

KG And with Louise helping you sustain your vision?

BE What strange beast is this?

LF It’s the dramaturg.

RealTime issue #55 June-July 2003 pg. 44