creating an affective community

jana perkovic: matthew day, intermission

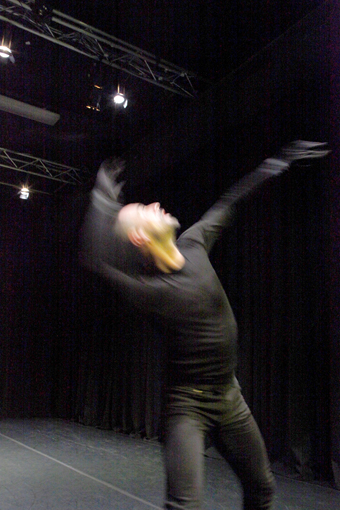

Matthew Day, Intermission

photo Rachel Roberts

Matthew Day, Intermission

MATTHEW DAY IS ALMOST CERTAINLY THE BEST OF A NEW GENERATION OF AUSTRALIAN CHOREOGRAPHERS. HE EXPLODED ONTO THE DANCE LANDSCAPE IN 2010, BRINGING AN ORIGINAL AND FULLY DEVELOPED POETICS SEEMINGLY OUT OF NOWHERE. HIS SERIES OF EXTREMELY SIMPLE, BUT CONCEPTUALLY RIGOROUS WORKS HAS CAPTIVATED THE AUDIENCE, AND AUSTRALIAN DANCE IS ALREADY IMMENSELY RICHER FOR IT.

Intermission is the final part of a trilogy that began with Thousands, in 2010, and continued with Cannibal, in 2011. In each part, Day explored the empathetic effect of absolutely basic movement: first stillness, then pulsating repetition. In Intermission, the focus is on undulating, rhythmic sway. The works are colour-coded: Thousands was gold, Cannibal pure white.

Intermission is black. We enter, one by one, a black box. A human figure is barely visible on a darkened stage: the lights are on us. The lights slowly dim, plunging us into a few minutes of pitch black. When the stage lights up, Day stands still, in casual black clothes: jeans, sneakers, gloves, and black masking tape where a line of skin might show between the cuffs.

As James Brown’s soundscape of a single droning, thundering sub-bass line sends pulsating tremors through our bodies, a sound more felt than heard, Day begins to almost imperceptibly rock left to right. His micro-shuffle grows, reaching shoulders, elbows, neck, arms, knees, until kinetic waves are flowing through Day’s entire body. This is not exactly choreography: rather, it is controlled movement. The only betrayal of the performer’s skill and training is in the constancy of rhythm and evenness of gesture: while strenuous, the movement never exhausts the body. The point of these pieces is not to explore endurance or produce exhaustion, but to maintain constancy.

Day’s works do not happen so much on stage as in one’s body as one watches. The real spectacle of these pieces is not in observing and admiring the dancing body, but in observing how being in the shared space with a moving body affects one’s own. The palpable rhythmic waves of kinetic energy emanating from the dancer, dense and tight and unrelenting, gradually build into very strong tension within one’s own body. A fellow spectator confided that during Thousands (an extremely still, slow piece) he felt an irresistible urge to stand up and do something, anything. Day has said elsewhere that he choreographs energetic exchange between performer and spectator: a choreographic situation that cannot exist without an audience. This is a more technical translation of what I try to describe to members of the general public, while queuing for the auditorium, as “it might upset your digestion.” “Should I not have gulped down my dinner?” asks one, half-jokingly. “That’s right,” I answer, very seriously.

Matthew Day, Intermission

image James Brown

Matthew Day, Intermission

Intermission, however, is comparatively light on one’s body. The pulsating, wave-like physicality that Day employs creates a light, but literal, hypnosis, a wandering focus, not dissimilar to boredom, but with a liberating lining of calmness. Our feeling of time and spatial proportion blurs into a drifting vagueness of perception. Suddenly, Day has shifted through the space, drawing ever-larger circles, one minute rocking a step at a time. I am light-headed, if not quite dizzy. At one point, I wonder if there is a way to test this effect, like in stage show hypnosis: how many of us would quack if asked? Would that make dramaturgical sense? Our bodies are tense, but there is a relief in the repetition: like jogging or disco dancing, this is a relaxing tension.

Meanwhile, Matthew Day’s rocking has morphed multiple times: from a sideways push/pull to a figure-eight arms loop, then back to a simple rocking with his head tilted back; shifts that feel both momentous and imperceptible. As usual, the eye perceives reference where there might be none: a preparation for strenuous activity; the rocking of anxiety or stress; repetitive industrial labour; mystical dancing; the liberating and oppressive capacities of a low-frequency repeat cycle. But Day channels no emotion, just blank focus, a mind merged with motion. When the work ends, it feels like any time at all might have passed.

To fully appreciate Matthew Day’s work, it is necessary to understand just how fundamentally it breaks not simply from modern dance, but from the full canon of modernist thought: the imperative of equating being with movement (not simply forward, but all kinetic acts of purposeful movement), a constant shedding of present for the future, the Cartesian individualism that posits the thinking subject as tragically severed from the world, and what Teresa Brennan (Exhausting Modernity, 2000) calls “the uniform denial of the transmission of affect.” In its small way, by slowing down time and expanding space, by creating an affective community, by rejecting spectacle for co-presence, Intermission is a demonstration of another way of being in the world, of empathetic being together.

Dance Massive, Dancehouse: Intermission, choreographer, performer Matthew Day, dramaturgy Martin del Amo, sound designer James Brown, lighting designer Travis Hodgson; Dancehouse, Melbourne, March 17-19; http://dancemassive.com.au

RealTime issue #114 April-May 2013 pg. 32