Close to the heart

Virginia Baxter

My Mother India

In family lore there’s the insult that goes beyond the pale, the revelation that brings shame on the name and then there’s making a film. There may be a market hungry for reality but what about the wash up in the lives of filmmakers who risk being excised from the will or at least struck off the Christmas list?

At this year’s WOW International Film Festival organised by Women in Film and TV (WIFT), an event jam packed with shorts, features, forums and celebrations impressively curated by Jacqui North and her team, a special day of documentaries featured 4 films that negotiated some of the perils and pleasures of personal filmmaking.

Jessica Douglas-Henry’s Our Brother James is really a portrait of the filmmaker’s sister Alix and her learning to live with their brother James’ suicide at age 20. In exposing the holes in the family fabric that allowed a vulnerable boy to slip through, the filmmaker opens herself to some judgemental responses from the audience—”where were you?”, they niggle, and “why didn’t we hear from your mother?” When you enter this terrain, it’s too easy to forget it’s film you’re watching. To prove it Douglas-Henry describes the strands that disappeared in the cut, replaced by the power of Alix’s considerable screen presence and the power of her “story.” Jessica invites Alix into her “split focus” scenario. Together the sisters take the journey back to Geraldton, back to the house where Alix found her dead brother, back along the path of personal grief that led her to public action—she is now involved with a voluntary suicide prevention organisation.

The film begins at the remote family homestead and moves through a crossroads and onto the dusty road to Geraldton. Jessica drives the car and asks the questions. Somewhat uncomfortable on camera, she defers to her sister who’s easy with it. “I don’t want to sound crass,” said someone in the audience after, “but she’s great talent.” As with all family stories, truths conflict but here the filmmaker listens intently to her younger sister’s side of the story. At one point, in response to Alix’s memory, she directs the camera to follow the nape of a neck, a young boy in the street who looks alarmingly like James. But no matter how careful she is to be objective, as Alix watches her own child playing, Jessica’s eye drifts to the sand dunes around Geraldton. Much of the film’s strength lies in the evocative way Douglas-Henry locates the family drama in a very particular landscape.

Melissa Lee set out with a project to research Korean-American documentary filmmakers and wound up with something altogether more interesting. A True Story About Love exposes her problematic romance with her first Korean lover (Melissa is Korean-Australian) and simultaneously his friend, a Japanese actor (the star of Peter Wang’s Chan is Missing). Lee takes a while to shake off her ‘researcher’ role. When the actor asks her out she interrogates her own image, “How could I go out with him after what Japan did to Korea?” Like other good films in this genre (Dennis O’Rourke’s The Good Woman of Bangkok, Sophie Calle’s No Sex Last Night) this little film reveals some big truths about relationships. It mixes narration, confession into the mirror, with intimate conversations with the 2 men in and out of bed. Given the sheets are still warm, Lee’s subjects are understandably less than comfortable with her surveillance, sometimes confronting it. And the filmmaker is upfront when the Japanese actor unleashes some scary thoughts on race and sexual power which, in the end, she doesn’t really want to hear. As often happens in these films, there’s no happy ending. Lee follows her filmmaker’s heart and is left with only the hand-held.

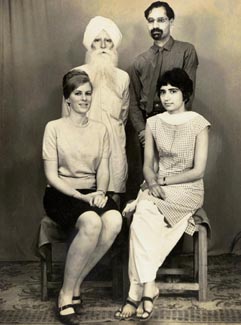

Safina Uberoi is nervous before the screening of her film. No wonder! Half the Indian community of Sydney has turned up for My Mother India and here she is with an opening shot of underwear hanging on a line. “One of the recurring horrors of my childhood was that my mother hung her panties on the washing line. I don’t know what Indian women wore under their saris but they never ever hung them where other people could see them.”

So begins a story more fascinating than any fiction I’ve encountered lately (outside my own family) and with an unforgettable cast of characters: Patricia Uberoi, the filmmaker’s mother who recounts her story so eloquently; JPS Uberoi the philosopher father; the Sikh guru grandfather who in the madness of his dying days “awesomely” relived Partition as the 1984 anti-Sikh riots raged in the streets; and his wife, the strong-willed grandmother who never forgave “the atrocity” of his treatment of her in 1947. The film weaves all this with the personal story of Patricia whose Canberra family could never bring themselves to visit her in Delhi, whose composure breaks only when she talks about giving up her Australian citizenship as an act of violence. You feel the intensity in the eyes of each family member as they meet those of the filmmaker and her husband (Himma Dhamija) behind the camera. The face of Patricia Uberoi, a study in itself, is interspersed with footage shot in India. At the heart of this film is a daughter’s homage to her complicated heritage. As we watch the fair-skinned faced Patricia kneading chapatis, Safina says, “My father is Indian and so is my mother, the identity of each a lifetime’s quest that is always being played out in complex ways.” Introducing the film to the huge crowd Safina speaks confidently about her reasons for “sacrificing” her family’s story to public scrutiny: “What happened to India happened to us”

Rob, the subject of Charlotte Roseby’s film Still Breathing, suffers from cystic fibrosis. Between drugs, hospital stays, a severely restricted lifestyle, he makes the most of what he knows is limited time. His calm insights into mortality conflict with the medical profession: “Death is seen by doctors as a looming giant ready to pounce if they do something wrong.” As he narrates the film his descriptions of the physical sensations of the disease, of lungs filling with fluid, are translated into images of rocks and water. At one point, his hospital bed is transposed to the beach. “Independence shrinks to body size,” he says, and it’s this restriction to his freedom that hastens the decision to list himself for a lung transplant, which may or may not work. My one quibble with this film was that it succumbed to the documentary cliché, adding text to tell us what happened when the cameras stopped.

As Safina Uberoi said in the afternoon forum, while personal documentary is not for everyone, the challenges involved in it—including the ones to do with confronting the subjects of your work, ie your family and friends—is great discipline for any filmmaker.

Our Brother James (52 mins), director Jessica Douglas-Henry, producer Mary-Ellen Mullane; A True Story About Love (27 mins), director/producer Melissa Lee; My Mother India (52 mins), director Safina Uberoi, producer Penny McDonald; Still Breathing, director/producer Charlotte Roseby, producer Nell White. WOW International Film Festival, Chauvel Cinema, Sydney, Oct 20.

RealTime issue #46 Dec-Jan 2001 pg. 18