Clara Law: an impression of permanence

Elise McCredie: The Goddess of 1967

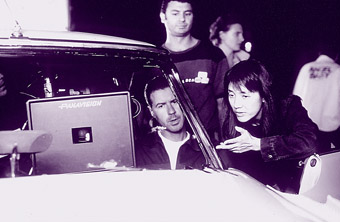

Clara Law directing The Goddess of 1967

Clara Law was born in Macau and graduated from Hong Kong University. She studied filmmaking at The National Film and Television School in London. Her feature films include The Other Half and The Other Half (1988), The Reincarnation of Golden Lotus (1989), Farewell, China (1990), Autumn Moon (1991) and The Temptation of a Monk (1993). Floating Life (1996) was her first film after re-locating to Australia and was co-written with her partner, Eddie Fong. The Goddess of 1967, also co-written by Fong, has garnered a number of international awards including Best Actress for Rose Byrne at the Venice Film Festival and Best Director at the Chicago Film Festival.

I heard that the inspiration for The Goddess of 1967 came from a road trip you and Eddie did in 1997.

It was our first trip to the outback. We came to Australia in 1995 and when we finished Floating Life we realised we didn’t know very much about Australia. So we bought a 4-wheel drive and went into the outback for 18 days. Out of that trip I got stuck in my head 2 places: Lightning Ridge and White Cliffs. So Lightning Ridge is Goddess and White Cliffs will be The Mechanical Bird (Clara’s next film).

Did the story for Goddess come while you were in the outback or did you have the idea before you set out?

At that time we wanted to do something on the dark side…because what Eddie and I had been doing was more to do with the positive side, nothing to do with what is irrational and hurtful to people. I think that is part of human nature and we wanted to look into that. So that was the idea, the first stage. Then we went to the outback. We thought somehow Lightning Ridge, and people who have the kind of existence where they work underground, seemed quite probable to fit into this idea of the dark side.

It’s an interesting metaphor that reflects the theme of the film—people burying their past and their secrets. Did the characters emerge after you had discovered the location?

We slowly developed the characters. The Japanese man came first and then the blind girl. We felt she had to be blind, we didn’t know why, but we just felt she had to be physically handicapped. If she’s blind and living independently, then she is connected in a way to something higher than what you can normally feel or materialise. We thought it would be interesting to put that type of character against a guy that comes from a society that is totally materialistic, a guy who has nothing to do with the spiritual side, who is very disconnected, very departmentalised. We thought if we put them against each other something interesting would happen.

His attraction to the car (The Goddess) is because it’s a physically beautiful thing whereas her attraction is its history, its emotional, intangible presence. The 2 characters have a very different relationship with the one car. How did the car come about?

We were looking for something for him to collect because he comes from an affluent society. Material stuff is easily accessible and it defines you as a person if you have collections. In a way that is what to us is the Japanese image. When we saw a friend’s Citroen DS we knew it had to be this. What we found out later fitted into the story. The fact that it’s an icon, that it’s such a futuristic car, its legends with (French President Charles) De Gaulle and French movies. Totally not part of Japan. It fits into this whole thing of modern technology and how man can behave like God, and he can actually be God when he creates something so perfect, and yet it’s still only a car. It just fit so perfectly with this guy who’s looking for a goddess in a car and finds a goddess in a girl. It was a coincidence but also a stroke of fate.

You have a very organic approach to scripting. You start slowly and then build the story.

We are never story driven. I think we are more character and theme driven. Sometimes we will just start with an image or something that’s been nagging me…if you start from a story it can become very superficial, very external, and that’s not something we’re interested in.

In a lot of ways you remind me of a painter. You’re so interested in composition and images, very much the art of cinema.

This is what I believe. I think cinema is telling a story through the images, images are very very important. I would rather rely on images than dialogue. I think they complement each other but I like to use dialogue in a poetic way rather than just disclosing information. I hate trying to describe through dialogue. If you want to describe something you do it through visuals.

Both Floating Life and The Goddess of 1967 are films where characters are taken out of their natural environment and placed in alien landscapes. Is this theme of displacement something that has particular resonance for you?

Probably, because that’s what I’ve felt. Even before I was living in Australia…when I was living in Hong Kong and in Macau, where I was born, I felt the same…always there are 2 people in me, one that goes through the emotional trauma and pain that everybody goes through, but there’s also another side that is very strong in me, that sits outside and looks at myself. I’m never very attached to things so most of the time I like to observe. I don’t like to possess. I don’t need to possess anything so I like to observe and react.

Do you feel the same way about place? You’re not attached to place?

I think I’m attached to things in bigger terms, things that are beautiful…but I’m not especially attached to any place. You’re attached to your memories but then you’re also aware that memories are in the past and you have to keep going forward. At the same time, there’s this strong awareness that life is very transient, there’s a beginning point but also an ending point…Probably that’s because I have a very traumatic memory of my brother. My eldest brother died when I was very young. So, mortality and the feeling that nothing is forever was very strong in me as a kid. Instead of going away it grew in me, this feeling that nothing is forever.

It’s interesting that you became a filmmaker because by making films you create a permanence. Your films will last beyond you.

Exactly. This is something very revealing about my character. When I was a kid I loved doing theatre, I loved directing plays. When I was in my last year in high school I directed a play that was an adaptation of Joan of Arc. It was entered into an open school competition and I won all the awards. We were delirious with happiness and I went backstage when it was all finished and we were packing and talking about where we would go to celebrate and then I felt really down, very depressed, and I didn’t go anywhere that night. I went home and I wanted to have a great cry. I suddenly felt very empty that it was finished. All this energy that you put in, all finished. From then on I didn’t do any more theatre. I stopped altogether. I started writing poetry and prose again, trying to find a means to express myself. But I knew I would never do theatre again because it was so sad for me.

You moved to Australia 6 years ago. Was this because you felt you could grow more freely here as an artist? Did you feel confined by the expectations placed on Hong Kong filmmakers—the martial arts movie genre?

That was a very big part of it. We felt a pressure in Hong Kong where you had to make a certain kind of film. A genre film and there was no alternate, independent cinema. Then my fourth film Autumn Moon, that won the Golden Leopard in Locarno, was ignored. In Hong Kong they just want movies to make money and entertain. When you try and walk the other path you are not looked upon with respect or support, and all that time Eddie and I felt trapped. No one around you is thinking like you or working like you or thinking you should be working like that. You’re trying to grow and move forward as an artist but you have to always pretend that you are part of this mainstream. We were not part of the mainstream and we knew we would never be. In 1993 we came to Australia to do post-production on Temptation Of A Monk and the more we stayed here, the more we felt that this is the place we could spend half of the year writing and recharging, while we spent the other half working in Hong Kong. At that time Autumn Moon was being released in Australia and received very good reviews. While we were working here we wrote the first draft of Floating Life which we showed to producers and they were interested in developing it. So slowly and gradually we stayed.

You said Hong Kong doesn’t support artists beyond commercial interest. Do you think Australia is any different? Do you think this country supports filmmakers throughout their careers?

Everything is relative. I won’t say that it is heaven here but I think to a certain degree you have a lot more channels to turn to and to do things that are different. This is what I felt when I first came here. I know now it is getting a bit more conservative but probably that’s not just Australia, it’s a worldwide thing. It is very unfortunate and depressing. The big money is now getting into arthouse films. A lot of arthouse films are not arthouse any more. It’s degenerating into something else.

So what is the solution for filmmakers?

You have to challenge yourself to keep getting closer and closer to what you hope is a work of art and you just have to try to keep doing that because there is no other choice.

Does your next film The Mechanical Bird explore similar areas to Goddess?

With Mechanical Bird we are exploring a different space and time. What Eddie and I share is a concern with the meaning of our existence…the spiritual side…if you look up there and then look down and see all these people —and us. Why us here on this planet? So it’s what’s out here on the planet and what we are, actually, inside. The macro and the micro is what intrigues both of us and why we move from one story to another in different ways.

The Goddess of 1967, distributor Palace Films, is currently screening nationally

RealTime issue #43 June-July 2001 pg. 13