Circus: second class artform?

Antonella Casella, Contemporary Circus

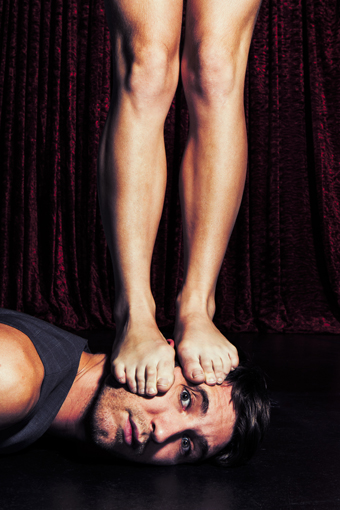

Skye Gellmann, Blindscape, Next Wave Festival 2012

photo Sarah Walker

Skye Gellmann, Blindscape, Next Wave Festival 2012

Contemporary circus is a wonderfully open form. It harnesses a multitude of approaches that stem from the notion of ‘Circus’ as the central informing principle. There continues, however, a prevailing opinion that circus skills should only be harnessed for performance when they reflect a narrative/contextual intent—that the display of circus skills, in and of themselves, is somehow gratuitous.

It seems to me that underlying this attitude is a belief that circus as an artform is somehow second rate unless it is woven into another, more worthy, artform such as text-based theatre or contemporary dance.

While I am in no way arguing against the use of circus in conjunction with other elements—text, movement, narrative, or character—I would like to make an argument for the acceptance of circus in its own right.

Over the last year I have seen a series of new works from emerging companies that demonstrate the unique role circus skills play within a performance text. In these pieces, circus skills are used variously as metaphors, character traits, moments of narrative exposition, key elements of mise en scène, heightened atmospheric moments or avenues for creating tension, suspense, surprise, shock or as ways to skew reality and challenge conventional perspectives. At the same time, the acrobatic bodies are used as sites to explore gender, sexuality and race. These works also consider the possibility of circus as pure spectacle, as part of the interplay between form and content.

Skye Gellmann, Blindscape

Skye Gellmann’s Blindscape can be reduced to two main elements: audience members individually navigating the open space through narration and sound effects from an iPhone; and two performers pushing the boundaries of their physicality, as individuals, with each other and with the audience.

Pure spectacle arrives as an element when the artists perform feats of extreme acrobatics on the black circus pole which is the visual centrepiece of the work. The question for me at this point, is what is the iterative effect of this moment? We, as audience members, expect this piece to include circus, and have been watching a series of body movements leading up to this point. Yet until now, all of the physicality could arguably be described as heightened, realistic, dramatic expression. Is there a moment where the work stops being contextual, and presents a moment of pure spectacle? Or has the gradual build-up of dramatic body movements ensured that this moment is just another in the fabric of exploration found in this piece?

Melissa Reeves, The Lost Act

With The Lost Act, playwright Melissa Reeves has created a unique script which utilises a kind of vaudevillian realism, much along the same lines as the literary genre of Magic Realism. In this work-in-progress (directed by Suzie Dee) Reeves collapses the naturalistic world of her characters with that of a vaudeville show. Throughout, the relationships between performers in a circus act completely mirror the relationships in the dramatic narrative. The plot revolves around a young set of siblings in search of their lost parents, who once performed an infamous circus act. At the same time, the siblings are themselves seeking to create their own new act, or, perhaps, recreate that of their parents. Within this plot, Reeves explores notions of identity in a post-colonial world. It is a world in which nothing is quite what it seems, and reality itself is a performance.

Once again, like Blindscape, The Lost Act allows for the possibility of spectacle for its own sake, with a number of scenes that present pure circus skills. However, these are more than mere divertissements, as they are an integral part of the world that is being made. It would be interesting to see how this interplay between naturalism and vaudeville evolves in a full-scale production, so I hope this show reaches the next round of development.

Polytoxic, The Rat Trap

Polytoxic, The Rat Trap

photo Stills by Hill

Polytoxic, The Rat Trap

Queensland company Polytoxic’s The Rat Trap is, on one level, about pure display from go to whoa. It tells the tale of Siamese twins, separated at birth and reunited in a Tiki bar where burlesque acts are indistinguishable from the extraordinary lives of the artists who inhabit them. The show has powerful themes, yet the pleasure, skill and showiness of the circus sweeps around these, giving us a sense of being at some kind of fabulous cabaret, rather than at a serious piece of theatre. At the same time, because the characters are performers in a Tiki Bar, the circus skills are to some extent, though not completely, motivated actions within the narrative. I would call the circus in this context a kind of “Nietschean excess”—the circus is representing that which is beyond definition, or limitation. It is not hiding the narrative, it is exploding from it! If The Lost Act is vaudevillian realism, The Rat Trap is burlesque hyper-realism.

Rat Trap’s vignettes evoke fantastical ideas, but the physical exploits within them are real. This show totally up-ends the idea of reality, and inspires audience members to question the very notions of place, presence and identity, all the while convincing us that we are in an escapist dream. Pure spectacle is the essence and the trump card of this show.

Sara Pheasant, Leggings are not Pants

In Leggings are not Pants, Sara Pheasant, directing performers from the Women’s Circus in Melbourne at 45 Downstairs and Gasworks Circus Showdown, deftly uses circus to heighten themes of gender, sexuality and, ironically for circus, the mundanity of everyday life. For example, a group of women watching television perform a chorus of naturalistic movements which build to become spectacular acrobatic tricks. This allows the skills to be interwoven in the piece, and yet emerge in key moments of strong spectacle. These function much like music in a film. They heighten the audience response to each scene, and occasionally provide an extended exploration of its emotional heart.

Casus, Knee Deep

Company Casus, Knee Deep

photo courtesy the artists

Company Casus, Knee Deep

Knee Deep, by Casus, is a unique work, inspired to some extent by the work of Circa, in that it combines highly athletic circus with a pared back aesthetic. Casus does, however, bring something new to the table. Over the course of the piece we see distinctiveness and quirkiness emerging from each of the cast members. This is mostly achieved through exploring each performer’s relationship with a raw egg. As a framing device, the egg also reminds us of the fragility of life and creates a striking juxtaposition with the strength of the circus performers. This show has a light touch, and invites us into the world it creates, yet, at times, as with many of the pieces discussed, often opens up moments for the celebration of pure circus acumen. Individual acts climax with great skills that seek, and receive, applause. In the context of this show, these spectacular moments are triumphs over the fragility of human existence.

These works demonstrate that circus, even when it is presented, arguably, as skill for its own sake, is always doing more. Circus is much more than a trope or a narrative device. It is a complex ‘body of representation’ which resonates uniquely in each work.

Circus artists/creators seek to use circus skills in performance for myriad reasons: to harness a populist form; to develop a craft they have been honing for years; to use circus as a history of representation from which to draw images, metaphors, characters; to work with an artform that offers freedom from linear, text-based, narrative-driven theatre; and, ideally, freedom from the gendered and cultural stereotypes of dominant discourse.

Ultimately, circus-based theatre makers draw from all of these inspirations to create their work. First, and foremost, they select circus skills ipso facto, for their own sake. Circus is the form from which all else follows.

Blindscape, PACT, Sydney, 19-29 June and touring throughout 2013; The Lost Act, presented as a rehearsed reading in 2012, is scheduled for development in 2013-14; The Rat Trap premiered in 2012, with further seasons in 2013; Knee Deep is touring internationally this year.

RealTime issue #115 June-July 2013 pg. 14-15