Bringing Russian art to light

Chris Reid: Moscow Biennale

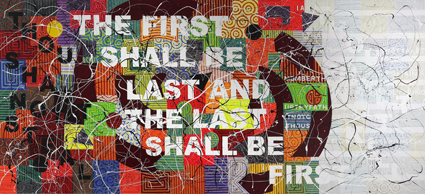

Richard Bell (Australia, 1953), One Day You’ll All Be Gone (Bell’s Theorem), 2011

courtesy of the artist and Milani Gallery, Brisbane

Richard Bell (Australia, 1953), One Day You’ll All Be Gone (Bell’s Theorem), 2011

Bulgarian artist Samuil Stoyanov’s video 10 min Geozavod (2012) shows the artist whirling a light-bulb on the end of a cable around his head in the unlit rooms of an art museum. This work epitomises the 5th Moscow Biennale of Contemporary Art, which is entitled More Light (Bolshe Sveta). The swinging light-bulb becomes a metaphor for consciousness—we’re aware momentarily of visible aspects of the world from which we construct a world view.

The Moscow Biennale’s main exhibition, of the works of 72 Russian and international artists, was strategically located in the Manege, the Central Exhibition Hall opposite the Kremlin. In the catalogue, Biennale curator Catherine de Zegher discusses her approach to the Biennale and analyses the artists’ work, saying, “If I explain the concept of the exhibition through the description of the artists’ works, it is because they have wholly informed the conceptualisation process…The curator goes with the flow of energy that drives the whole project—the flow of impressions, ideas and interconnections. To do otherwise is to impose a determining framework predicated not on conversation, but on prejudice and an ordering model.”

De Zegher’s choice of artists is pivotal. Clear themes emerge, particularly political and social commentary, the environment, domesticity, the apprehension of space and time, and drawing as form and process. There’s the telling photography of Umida Akhmedova (Uzbekistan), who was convicted in 2010 of slandering the Uzbek nation in her documentaries on Uzbek life. Rena Effendi’s photography documents life in Azerbaijan and Chechen artist Aslan Gaisumov’s battered, bullet-riddled metal gates evidence conflict. Australia’s Richard Bell pitched a tent, labelled it Aboriginal Embassy and called it Imagining Victory, referencing Canberra’s Aboriginal Tent Embassy and foregrounding the universal issue of post-colonial politics. Irish artist Tom Molloy’s installation Protest (2012) comprises hundreds of tiny paper cut-outs of historical photos of protesters, sourced from the internet, showing that protest is eternal and demonstrating the internet’s capacity for information dissemination. Gao Rong, whose embroidered replica of the interior of her grandparents’ house was so impressive at last year’s Sydney Biennale, showed Guangzhou Station (2012; RT12, p10), embroidery-covered household goods packed into fake designer-label handbags, commenting on the fashion market and the superficiality of style and wealth.

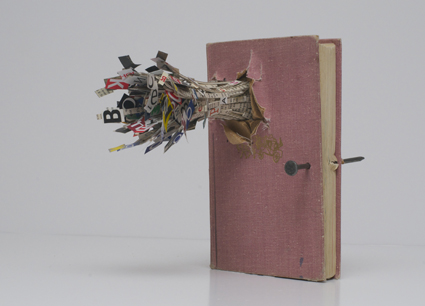

Aslan Gaisumov (Russia, 1991) (exploding book), In Memory of A. P., 2010, From the series ‘Untitled (War)’

courtesy of the artist

Aslan Gaisumov (Russia, 1991) (exploding book), In Memory of A. P., 2010, From the series ‘Untitled (War)’

Soviet suppression encouraged indirect or metaphorical artistic expression, a tradition that continues, and art in Russia is often politically flavoured. Russian group The Collective of Artists showed En Plain Air (2012), paintings of the Kremlin in white on a white ground, ironically acknowledging the father of Russian contemporary art Kasimir Malevich’s White on White (1918) and decrying censorship. Controversial Russian architect Alexander Brodsky’s sinister-looking installation, Unnamed (2013), suggests an entrance to a bunker—made of re-used timber, it’s like an old hut; there’s a neon M (for metro?) above the barred door, an eerie blue light emanates from within and it’s surrounded by an ocean of crumpled foil wrapping. Elena Kovylina’s video Égalité (2008) demonstrates Russian art’s satirical character—it shows a mixed group of people of all ages clambering onto a row of stools of different sizes that render everyone equal in height. In the snow, they stand facing the Kremlin as if ritually posing for a group photo, then climb down and wander off with their stools, the video touchingly revealing their individuality in order to challenge the dehumanisation of forced equality and conformity. The smallest participant, an elderly woman, lugs the biggest stool.

Much art addressed the universal issues of migration, colonisation and displacement. Alfredo & Isabel Aquilizan (Philippines/Australia) showed a convoy of skis and laden sleds as if a community is migrating through snowfields. Yin Xiuzhen’s Portable City: Jiuyuguan (2008) is a series of suitcases opened to reveal tiny model cityscapes, reflecting on both her constant travelling and the homogenisation of cities through globalisation. She also showed what looked like a collapsed brick wall with shreds of fabric between the bricks, suggesting the destruction of home. Russian artist collective Gorod Ustinov is named after the city of Ustinov which existed from1984 to 1987 before it was renamed Izhevsk. Group members born there in that period associate their artwork with a place which, to them, no longer exists, speaking of the transience of identity based on home. Chinese artist Song Dong simply displayed the innumerable household objects his mother accumulated in her home in his Waste Not (2005; RT13, p44-45). Waradgerie artist Lorraine Connelly-Northey’s Three Rivers Country (2012), made from found corrugated iron, chicken wire and fencing, was mounted next to, and resonated with, Richard Bell’s painting One Day It’ll All Be Gone (2012). Bell’s tent became a venue for artists’ talks, including one by other Australian artists Gabriella and Silvana Mangano on their video Sculpture Sequence (2012).

De Zegher’s strong interest in drawing is evident throughout. Australia-based, Poland-born Gosia Wlodarczak’s exquisite Frost Drawing for the Moscow Manege covered the gallery’s internal glass walls and balustrades. But it is light itself that is essential to this biennale. The Manege’s lower level is in semi-darkness, where Gaisumov’s gates are back-lit so that light beams emanate from the bullet holes. In the light-flooded upstairs level, Wlodarczak’s drawings are made visible by the light behind the glass. The Manganos’ video, in which they ‘draw’ in darkened space by manipulating objects under stark lighting, is like drawing with light, counterpointing Stoyanov’s video and recalling Malevich’s ultimate reductiveness. This is an exhibition of great visual power and beauty as well as deeply felt personal expression.

The Biennale also included 60 satellite exhibitions, assembled by local and international curators, involving hundreds more artists, mainly in prominent Moscow locations including the Moscow Museum of Modern Art, the Garage Centre for Contemporary Culture, the State Tretyakov Gallery and the State Central Museum of Contemporary History of Russia and in the cities of Yekaterinburg and Murmansk. And there were guest artist exhibitions, showcasing the work of significant figures, such as that of legendary Russian conceptualists Ilya and Emilia Kabakov at the Multimedia Art Museum.

The State Tretyakov Gallery of Twentieth Century Russian Art hosted the Biennale exhibition Modern Art Museum: the Department of Labour and Employment, involving 56 Russian artists and collectives. Curated by Kirill Svetlyakov and Sofia Terekhova, the exhibition addressed the role of the artist in post-Soviet Russia, the catalogue declaring, “The aim of the project is to trace the history of labour in Soviet and post-Soviet art, from its industrial to its nonmaterial forms, from the 1960s to the 2000s, and show how representations of labour, and the ways in which it is depicted, have changed as new artistic practices have evolved.” In the Soviet era there were no independent galleries, and the idea of the artist as worker, as producer and as commentator is re-considered in the context of post-Soviet Russian capitalism. The exhibition proposes that artists work outside the new commercial gallery system to retain artistic integrity.

In Moscow’s theatre district, the New Manege gallery hosted the exhibition 0 Performance—The Fragile Beauty of Crisis, involving 26 Russian and international artists. Inspired by the zero performance of the world economy following the GFC, the exhibition addressed the double meaning of the word ‘performance’— artistic performance and economic performance. Finnish artist Pilvi Takala’s contribution documents her masquerade as an unproductive office trainee whose eccentric behaviour draws criticism from fellow workers unaware of the trick being played on them. Interestingly, the month-long performance was made with the cooperation of the host firm, Deloitte, which presumably welcomed its staff’s reaction to non-productivity.

While at the Museum of the Revolution’s Biennale exhibit, I discovered in adjacent rooms a fascinating collection of Soviet propaganda posters issued in Uzbekistan in the 1920s and 30s when Uzbekistan was being absorbed into Soviet culture. Through the satellite exhibitions, the Biennale’s swinging light-bulb illuminated Russian history and culture generally, and opened its unique museology to consideration.

5th Moscow Biennale of Contemporary Art, Curator Catherine de Zegher, Manege Central Exhibition Hall, Moscow and other locations, 19 Sept–20 Oct

RealTime issue #118 Dec-Jan 2013 pg. 45