Bodyworks: dance constructions

Philipa Rothfield: Dancehouse, Bodyworks

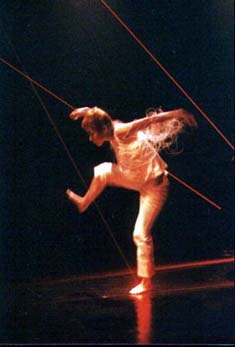

Eme Suzuki, Fragment for Children

Not only do people move in very different ways, their choreographic construction methods and priorities are also quite diverse. Phillip Adams’ Ending #1—part of a major work-to-be, shown in its infancy—afforded a forensic perspective on constructing dance. Whilst some might build a piece through the development of movement, Adams appears to work with an almost fetishistic use of objects, a strong musical presence and an enduring commitment to design, that is, the look of the piece.

Ending #1 begins with a toy plane wiggling along fishing wire the depth of the stage, to the sound of Ligeti’s signature piece for Kubrick’s 2001, A Space Odyssey. Whilst the music suggested an event of great moment, the plane looked absurd in its precarious journey towards the back of the room. A similar tribute to the object occurred when a glow-in-the-dark toy was reverently studied by the performers, then wobbled towards the ceiling.

I had a sense that the movement in Ending #1 was not developed anew but drew upon a now-familiar kinaesthetic which Adams recalls and reworks to fill in the spaces. Adams and Toby Mills danced about in g-strings with fox furs draped around their necks, whilst Brooke Stamp seemed to hang about onstage most of the time—until Adams and Mills enjoined her in a trio which looked faintly pornographic, suggestively lit by a bare light bulb swinging back and forth. I found the piece pretty witty despite its state of choreographic undress. Supposedly about extinction (God knows how that entered this version apart from the dead foxes, and a luminous dinosaur), Ending #1 signals a beginning rather than an ending. I look forward to its evolution.

The second half of Bodyworks Program 3 included performances by 2 Japanese artists, Masami Yurabe and Eme Suzuki. A striking feature of both pieces was the way in which neither drew upon any familiar lexicon of movement. Developed and repeated in a series of poignant movements, Suzuki’s Fragment for Children was very clear, simple yet powerful, her kinaesthetic persona a young girl facing life, dealing with the world in emotional terms. Beginning tentatively, expressing fear and anxiety, the work finished with a series of bows that presented a self at peace. Suzuki’s sincerity and commitment to her theme gave the work its dignity.

Yurabe’s Witness was a very different kind of work, less personal, subject to greater change. Witness begins and ends with a chair. The start was almost clownish but, by the end, the chair became less of a prop and more an object of existential moment. Yurabe’s movement was also quite variable. From comic, anarchic interaction with the chair as a means to enter the performative space, the movement took on a more dancerly character. There was an incredible elegance about his body in motion, also a presence and aliveness which suggested a degree of improvisation. The program notes mention improvised Butoh performance. I felt by the end that I would like to see other works by Yurabe; he has a performative edge that could go many places.

Bodyworks, Program 3, Dancehouse, Melbourne, Feb 20-24

RealTime issue #48 April-May 2002 pg. 29