belarus free theatre: an aesthetic opposition first of all

david williams: being harold pinter and the pianist

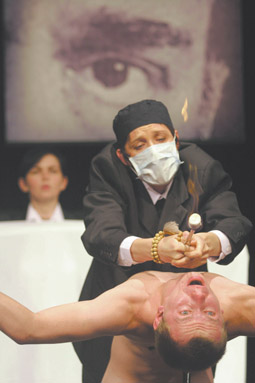

Being Harold Pinter, Belarus Free Theatre,

photo Trent O’Donnell

Being Harold Pinter, Belarus Free Theatre,

THE MINSK-BASED PERFORMANCE GROUP BELARUS FREE THEATRE MADE THEIR MUCH-ANTICIPATED AUSTRALIAN DEBUT WITH BEING HAROLD PINTER AT THE SYDNEY FESTIVAL, AND THIS WORK TOOK ON A GREAT POIGNANCY FOLLOWING HAROLD PINTER’S RECENT DEATH ON CHRISTMAS EVE.

Much of the excitement around this company’s work derives from its political context. Described by producer Natalia Koliada as “Europe’s last dictatorship”, Belarus under President Alexander Lukashenko is very far from a safe place to create political theatre. In a nation where every aspect of life, including artistic practice, is strictly regulated, Belarus Free Theatre work underground to produce uncensored accounts of life under the totalitarian regime. Co-founded in 2005 by Koliada and her husband Nikolai Khalezin, a playwright and journalist, the Belarus Free Theatre has created 11 productions, and regularly travels internationally, drawing attention to the plight of their homeland. For their efforts in daring to imagine a free and democratic Belarus, their audiences in Minsk have been arrested, performances broken up by armed police, actors denied exit visas, artists threatened and assaulted, writers banned from production and company members and their families fired from State-run institutions.

For Koliada, “it’s very complicated when you have family, when you have small children. When you get fired you cannot get any other job in our country…But we understand this. We have a very great teacher, who is Vaclav Havel, who told us we need to speak very loudly and openly in order to stop dictatorship. Otherwise we would just prolong this dictatorship.”

Attending a Belarus Free Theatre performance in Minsk is a clandestine experience. Performances take place in private homes, basements and cafes, rarely at the same place more than once. Performances often occur in the middle of the day, and audiences are notified by text message as to the time and location. According to Koliada, the desire has always been not only to resist oppression by using theatre to address forbidden topics, but also to produce a visceral and dynamic theatre aesthetic. “When we organise the theatre, we decided that it should be aesthetic opposition first of all. If we have a high standard of aesthetic opposition then…we could change aesthetically a society, and when we have such an artistic product then we could attract more attention for political changes.”

being harold pinter

When asked why Belarus Free Theatre chose to work with Pinter’s texts, Koliada replies: “when we read it we understood that he understands us better than many people who live in Belarus.” Even though the plays are not about Belarus, their inherent menace seemed to the company to perfectly capture the experience of contemporary life under Lukashenko. In Pinter, they found that there could be “an essence of violence in just words”, and Being Harold Pinter explores this in detail, using Pinter’s drama and commentary to sharply critique and devastatingly enact the violence that underpins intimate relationships and social institutions.

Adapted and directed by Vladimir Scherban, the performance incorporates Pinter’s Nobel Prize address as a springboard to analyse the hidden currents of his writing and simultaneously demonstrate the arbitrary demands that totalitarian regimes make upon the bodies of citizens under their power. Scherban’s textual montage blends Pinter’s speech with excerpts from six of his plays, and into this he inserts accounts from political prisoners in contemporary Belarus. It’s a startling interpretation, delivered at a pace that allows little space for the famous Pinteresque pauses. Questions swirl about the different needs for truth in art and politics, the possibilities of making political art, ways of negotiating the dissimilar responsibilities of the artist and citizen, and the violence inherent in dramatic language itself.

The performance begins with Pinter (Oleg Sidorchik) brandishing a cane, describing a recent fall he has suffered. As he speaks about his head hitting the pavement, and blood splashing, Sidorchik places a hand over his face. Another cast member sprays him with red paint and places a sticking plaster over his eye. Returning home, the news informs Pinter that he has died and, shortly afterward, that he has not, but rather that he’s been awarded the Nobel Prize. “So I’ve risen from the dead”, he declares.

Pinter reflects upon the beginnings of several of his plays, noting that “our beginnings never know our ends.” All he knew at the start were the opening lines. This reverie is radically broken as the Sidorchik turns on one of his colleagues. Cane pressed against throat, he makes a violent interrogatory demand: “What did you do with the scissors?” The world of the performance has disorientingly tilted on its axis. Is he still Pinter? The character Mac from the play The Homecoming (1964)? A secret policeman in Belarus? All of the above?

Being Harold Pinter is most effective in these early scenes—an utterly riveting, relentlessly paced and forcefully delivered theatrical presentation. Even simple exchanges bristle with menace and acquire accusatory overtones. The seemingly laid back opening conversation of Old Times (1970) reveals a deep vein of potential violence. “You lived with her” is transformed in the mouths of the Belarus Free Theatre actors from a question into a threat. Shortly afterward, an excerpt from Ashes to Ashes (1996) oscillates between intimacy and madness. “I’ve just paid you a compliment. In fact I’ve paid you a number of compliments.” The threats get less oblique as the performance continues, with Scherban’s treatments of Pinter’s The New World Order (1991) and Mountain Language (1988) recognisably mirroring the operations conducted in the name of the War on Terror. In The New World Order, a parade of torturers amuse themselves by first teasing, then mutilating a prisoner. One confesses to the other that these actions make him feel pure, and his comrade responds that this purity is because he is “keeping the world clean for democracy.”

Order itself becomes a form of amusement for the prison guards who populate Mountain Language, with violent acts deemed to have not truly occurred until they can be properly accounted for. A woman savaged by a guard dog has no injuries that can be recognised until she is able to name the dog that is to blame. Unless the dog gives its name, there has been no violence. Another woman’s husband has been mistakenly imprisoned, but the guards refuse to acknowledge that anyone but the Mountain people might be contained within the prison. Finally, after being punished for speaking in the forbidden language, the prisoner is advised that the rules have changed. They are now allowed to speak in their own language, but it is too late. The old mother has already been beaten to death for an infraction now deemed innocent.

Each of these sharp vignettes is introduced by the figure of Pinter himself, who reels from one desperate exchange to another, searching for truths about art and power. “Political language, as used by politicians, does not venture into any of this territory since the majority of politicians, on the evidence available to us, are interested not in truth but in power and in the maintenance of that power.” Coming as they do from a nation in which the maintenance of power involves the active repression of citizens, the Belarus Free Theatre are courageous theatre makers.

the pianist

In contrast to the dynamism of Being Harold Pinter, The Pianist is a largely static performance. In the dark Belvoir Street upstairs space, a grand piano sits centrestage with music stands scattered about. Within this simple staging, The Pianist is essentially a recital performed by Mikhail Rudy, intercut with narration from actor Sean Taylor.

Adapted from the memoirs of Polish pianist Wladyslaw Szpilman, the narration tells an extraordinary tale of endurance and survival in a world gone mad. Beginning with a series of portraits of life in the Warsaw ghetto in 1941, we follow Szpilman as he manages to escape transportation to the concentration camps, and finally traces his subsequent years in hiding in the deserted city. Concealed in an attic, lying quietly day after day, Szpilman kept himself sane by rigorously rehearsing every piece of music he had ever played, a silent discipline to help him ward off certain death. Music itself became materialised through memory, a way of mentally inhabiting better days and a means of survival through imagination. In an encounter with a German officer in the last months of the war, music literally becomes the currency ensuring life, as Szpilman successfully proves he is in fact a pianist by playing Chopin’s Scherzo in B Minor on an untuned, abandoned instrument.

As the voice of Szpilman, Taylor is suitably restrained, and Rachel McDonald’s direction is simple and uncluttered. The Pianist is hardly groundbreaking theatre, but is nevertheless quietly effective. Rudy’s passionate delivery of Chopin’s Nocturnes provides the emotional underpinning of Szpilman’s almost clinical account of his experiences. It’s as if Chopin’s music contained all that remained unsayable for Szpilman: the combination of the barely said and the emotive musical overflow makes The Pianist a frequently moving experience.

Belarus Free Theatre, Being Harold Pinter, based on the plays of Harold Pinter, adaptation, direction Vladimir Scherban, performers Nikolai Khalezin, Pavel Gorodnitski, Yana Rusakevich, Oleg Sidorchik, Hanna Solomianskaya, Denis Tarasenko, Marina Yurevich, producers Natalia Koliada, Nikolai Khalezin, lighting Stephen Hawker; Belvoir St Theatre, Q Theatre, Sydney Festival, Jan 6-Feb 1; The Pianist, based on memoirs of Wladyslaw Szpilman, concept, script Mikhail Rudy, director Rachel McDonald, performers Mikhail Rudy, Sean Taylor, design Jo Briscoe, lighting Stephen Hawker; Belvoir St Theatre, Sydney Festival, January 16-27

RealTime issue #89 Feb-March 2009 pg. 9