Being Stelarc

Gail Priest, Stelarc: Meat, Metal, Code: Engineering affect and aliveness

Stelarc, Extra Ear: Ear on Arm

photo Nina Sellars

Stelarc, Extra Ear: Ear on Arm

I am haunted by the goofy laugh that punctuated Stelarc’s 90-minute presentation of his extraordinary and gruesome body of work (or perhaps work of body). This laugh erupts from him at curious moments—an awkward, teenage boy-like honk—providing a real sense of the man inside the artist and offering more insight perhaps than standard theoretical analysis into his artistic and personal motivations.

The title, Meat, Metal, Code, neatly encapsulates his various approaches. Meat covers his suspension works in which the artist, and more recently willing participants drawn from the body modification scene, are suspended in space by butcher’s hooks. The body floats freed of weight yet we are more aware than ever of gravity’s awesome power. Meat also incorporates Stelarc’s most challenging work, Extra Ear in which he is growing an ear on his forearm (no doctor would agree to let him grow it on his head). Stelarc pulls up his sleeve and shows us the quite perfect looking ear in relief that is emerging, the cells and blood supply forming over an architecture made from a micro pore inserted under the skin. When completed, the ear will have its own microphone in order to record and transmit sounds, a process tested and found to be successful when the operation was first undertaken.

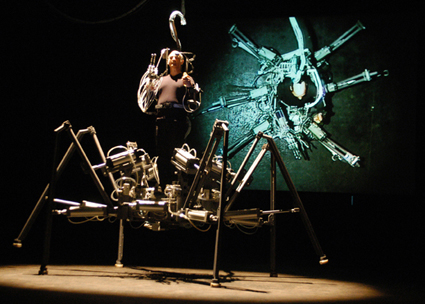

Stelarc, Exoskeleton, photo Igor Skafar

Metal addresses the various robotic and biomorphic appendages that Stelarc has created to augment his own body, or later, to act as independent agents. These include his third arm, an upper body exoskeleton, a six-legged walking machine and finally a swarm of dancing robots sporting screens for heads. Code is incorporated into all these works of course, but it also takes the spotlight in pieces such as Prosthetic Head, an illustrated 3D representation of the artist, freckles and all, that responds to questions and stimuli. Stelarc had this head lip-synch to early 20th century tenor Enrico Caruso as the conclusion of his presentation. As ISEA executive creative producer Alessio Cavallaro quipped, “it ain’t over until the Prosthetic Head sings.”

Mixed among Stelarc’s own work were fascinating examples of scientific developments that excite him: all terrain insect robots powered by “wegs;” electronic circuitry that can be applied directly to the skin like a fake tattoo; and organ printing experiments in which standard Hewlett Packard technology is adapted to utilise living cells instead of ink to build up functioning organs layer by layer.

This catalogue of information flowed mostly historically and with no real delineation between Stelarc’s art and the speculative research, but we never really heard much as to why he wanted to make these things, why push his body to these extremes. Only during the very short question time did the artist actually speak philosophically about his work. Quoting mathematician and philosopher Alfred Whitehead, he says that our imaginations are only as interesting as our instruments, so perhaps he feels the responsibility to create new and better ones using his own body as the raw material. When asked about science fiction Stelarc says he is not so much interested in speculation but rather in “the direct experience of an actualised interface” and that the role of an artist is to “generate contestable futures.” Now we were getting into some meaty (metallic, code-rich) discussion but the MCA was closing and we were kicked out.

So I am left with Stelarc’s laugh—his bodily eruption of excitement and delight at these futures that he has built himself into and built into himself.