Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

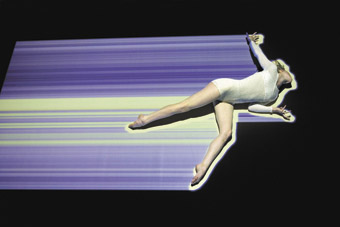

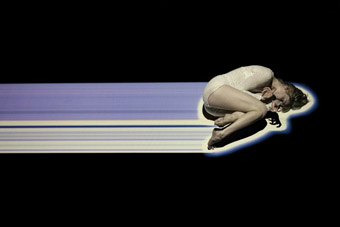

Trish Adam, HOST (video still), original cinematography Carla Evangelista

FOR CHILDREN, BEES ARE THE SUMMER TERROR OF THE CLOVER LAWN. OUT THE CAR, ACROSS THE PARK TO THE BEACH, PRICKLES ARE BAD BUT BEES ARE WORSE. (I’VE JUST CONDUCTED A SURVEY OF ALL THE PEOPLE I CAN IMMEDIATELY FIND WITHIN 20 METRES OF WHERE I’M SITTING AND THEY ALL REMEMBER THEIR FIRST BEE STING.) SO BEES ARE THREATENING, YET HERE BEES ARE, IN TRISH ADAMS’ HOST, GLIDING ABOVE AND GENTLY SETTLING ON HER UNPROTECTED HAND.

Trish Adams has previously collaborated with scientists at the University of Queensland where she worked with Associate Professor Victor Nurcombe on the transformation of her own stem cells into cardiac cells (machina carnis, www.realtimearts.net/article/issue68/7937). This time she worked with Professor Mandyam Srinivasan’s Visual and Sensory Neuroscience group at the Queensland Brain Institute. Srinivasan is famous for his work on bee vision and navigation.

[Three interesting facts about bees: 1. Bees can be trained to detect camouflaged objects. 2. Bees navigate by using the speed at which images move across their eyes—they fly down the middle of a tunnel by keeping the image speed the same at both eyes; they land by adjusting their descent speed so that the image speed at the eye remains constant. 3. Bees are lateralised in their learning, just like people are right and left handed. ]

Into the Bee House goes Adams and finds no protective suits, just your normal everyday science types, thousands of bees and an uncomfortable feeling of vulnerability. A couple of researchers, Dr Peter Kraft and Carla Evangelista, help out by filming the feeding sessions (high speed at 250fps) and providing the skills and patience needed to train the bees to feed from Adams’ hand. Film is edited, a soundscape designed (by roundhouse, www.roundhouse.tv), and the installation set up at the UQ Art Museum—a bland corporate box of a building refurbed into a gallery.

Enter through the glass doors, straight ahead to the far corner and down the stairs. Step off the stairs and a waft of honey rises up, faint, but clear. Small room, low ceiling, padded lowset bench. Sit and face the end wall/screen. Glass panel walls to the right and left shine in the darkness, recursively reflecting the far end projection. This is the installation space, quiet, intimate. Maybe two or three people can get in there without violating personal space rules. The screen shows a video laterally split between two images. One third is honey, dripping in real time, close up, luminous and golden. Two thirds are a cropped detail of hands. The hands are crossed lightly, one nestling in the other. Inside the cupped palm of the uppermost hand is the honey the bees were trained to seek. The hands are still, incredibly so, one slight thumb movement the only action. Around the hand float soft, purposeful bees, huge and close-upped, paced slow by the high speed video. They glide about, land to feed, take off, land on a finger, wait, take off again. They make no sound. It is as if the bees hover weightless above a familiar surface, collecting samples before returning to base.

And throughout are the hands and an unconditional offering of food. The bees too act without conditions, offering their labour to the continuity of the hive. The food they collect is not only for themselves but for others, just as the glistening honey in the palm is not for the palm itself and the outstretched hands are for the bees and not for the hands themselves. The artist feeds the bees, the scientists film the artist. We watch the bees, the honey and the hands. An exchange between systems. Biology.

HOST, artist Trish Adams, The University of Queensland Art Museum, Brisbane, March 6-April 6

RealTime issue #84 April-May 2008 pg. 31

© Greg Hooper; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

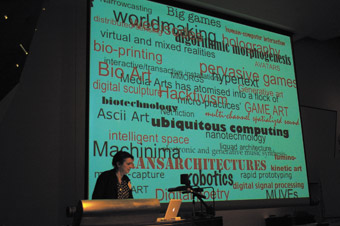

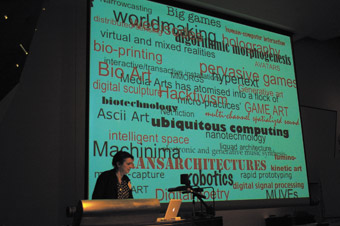

THE AUSTRALIA COUNCIL’S INTER-ARTS OFFICE NOT ONLY FUNDS PROJECTS THAT CAN’T FIND TRADITIONAL ARTFORM HOMES BUT IT ALSO ENCOURAGES VERY DIFFERENT ARTISTS TO TEAM UP AND VENTURE WHERE NONE HAVE TROD.

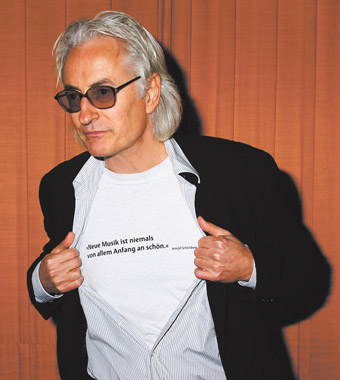

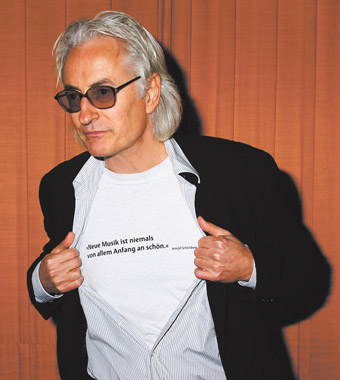

Artlab funding criteria require not tried collaborations but new ones; experimental, research-based and risk-taking approaches; and, if the project involves creating technologies, they must be new. It’s a tough brief requiring a strong sense of vision, teamwork and, not least, pragmatism: significant cash or in-kind contributions have to be found beyond the Australia Council’s $75,000 funding of each project in 2008. Twenty two applications sought a total of $1.5m; two succeeded for a total of $150,000.

Thinking Through the Body comprises the artists Jonathan Duckworth (artist and architectural designer specialising in the development of real time graphical environments), George Khut (artist working in the area of sound and immersive installation environments), Somaya Langley (sound and media artist), Lizzie Muller (curator and writer working at the intersection of art, technology and science), Garth Paine (sound designer, installation artist, interactive system designer) and Catherine Truman (contemporary jeweller and object-maker). The collaborators intend “investigating the use and potential of touch and movement in body-focused interactive art. The group will use a variety of body-sensing technologies to explore the possibilities of interactive art that links technical experimentation and artistic expression.”

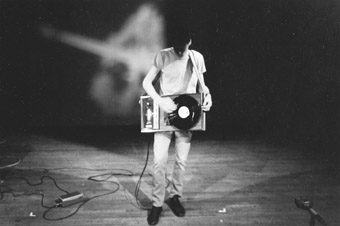

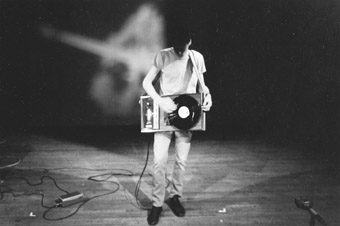

The Transmission Project: Wheel, Water, Wind brings together Rod Cooper (hybrid instrument maker), Robin Fox (sound artist working with live digital media), Jon Rose (violinist, composer, writer and installation artist), Jim Sosnin (a specialist in acoustics, audio electronics, sound recording and computer music) and German artist Frieder Weiss [see interview] to develop “a wireless data technologies platform for designing human/machine interfaces. The team will investigate the compositional, installation and performance possibilities of the design, presenting works in progress on the themes of Wheel, Wind and Water during the testing stage of development.”

Andrew Donovan, Director of the Inter-Arts Office of the Australia Council, is pleased with the 2008 Artlab funding results. In his report he writes, “The panel was particularly responsive to projects that detailed a concise and logical research methodology, whilst clearly articulating potential artistic outcomes for the project. The panel was also responsive to applications that were genuinely collaborative in nature, reflecting the objective of the ArtLab program to nurture and support new interdisciplinary, artistic collaborations that offered the best opportunity for the development of new knowledge, artistic innovation and creative risk-taking.”

Donovan told RealTime that he welcomes the diversity of arts practitioners in each project, the range of age and experience and the geographical spread. He’s especially impressed with the number of experienced artists willing to place themselves in very new collaborative circumstances. The assessment panel, he says, were particularly taken with the research and development process embodied in the projects. “This can develop a platform—with innovations in software and hardware—to push hybridity forward, making it easy for other artists in the future to break through technical barriers.” RT

RealTime issue #84 April-May 2008 pg. 31

© RealTime ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

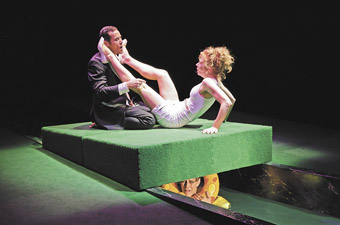

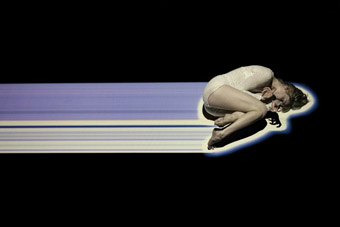

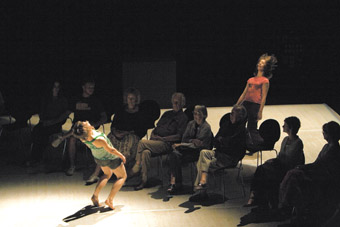

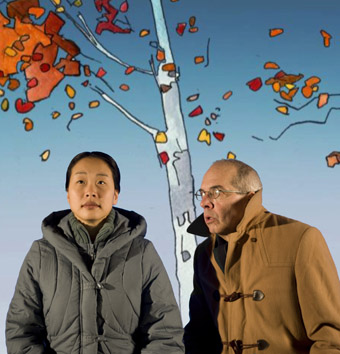

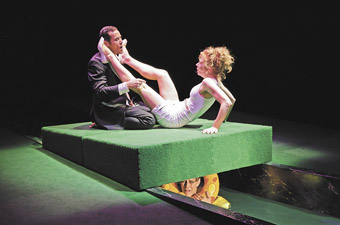

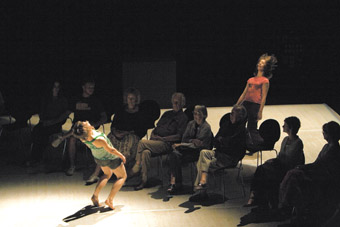

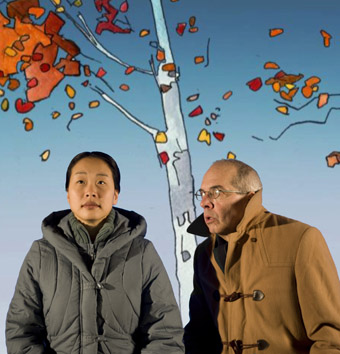

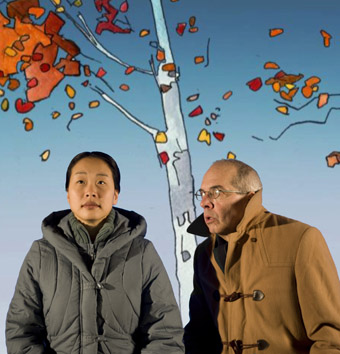

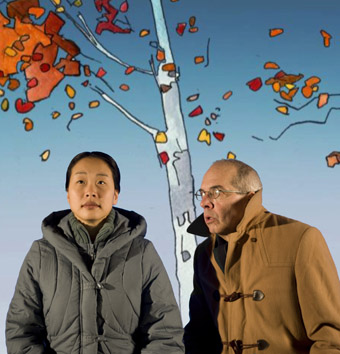

Akram Khan, Sylvie Guillem, Sacred Monsters

photo Nigel Norrington

Akram Khan, Sylvie Guillem, Sacred Monsters

TIME STANDS STILL IN THE MOST INTERESTING WAYS IN EMBRACE: GUILT FRAME. BECAUSE THE PERFORMANCE BALANCES ON A PIVOT OF STILLNESS AND EXTREMELY SLOW MOVEMENT, THERE’S INEVITABLY A PICTURE-LIKE QUALITY TO THE WORK ENHANCED BY THE ACTION BEING RESTRICTED TO A SMALL GILT FRAME THAT LIMITS OUR VIEW TO THE HEADS AND UPPER TORSOS OF TESS DE QUINCEY AND PETER SNOW. IT’S THE TIME OF THE ART GALLERY, EXCEPT THAT YOU CAN’T MOVE ON AFTER A FEW MINUTES OF VIEWING. YOU STAY STILL; THE PICTURE KEEPS CHANGING FOR SOME 50 MINUTES.

What we see pictured remains peristently enigmatic, always suggestive, of individual emotional and physical states, possible relationships, the history of painting even—such is lighting designer Travis Hodgson’s subtle texturing and profiling, his shifts in depth of field, evoking Carravagio, Vermeer, Rembrandt and more.

De Quincey and Snow work their way through a set of states common to The Natyashastra (an ancient Indian text) and Body Weather (the contemporary Japanese movement discipline; see RealTime 83, page 45 for an interview with De Quincey) but never literalise them. A smile is a smile, a grimace a grimace beneath which might be ecstasy or anger. But it’s the slow unfolding of these states that compels one to look for complexities, tensions, shared pleasures, changes in mood. Humans enjoy peering at portraits, painted or photographed, as if endlessly rehearsing primordial encounters with strangers in our evolutionary development. Embrace: guilt frame allows us to read faces with a rare intensity, registering tiny details, forming impressions, re-evaluating, never resolving. It’s a peculiar pleasure made palpable by disciplined performers who ease themselves into a temporal state slower than our own and invite us in.

But there’s more to embrace: guilt frame than faces—radical if slow changes in perspective, supple tonal shifts and endless evocations. There are moments when the performers lean out of the frame towards us, or recede into its deep dark interior; a moment when de Quincey turns ever so slowly, low in the frame, only her head, its back to us, providing support—it looks simple but must require great strength. There are moments that appear Gothic—the prolonged shudder in the residue of a laugh, Snow’s shaded face appearing to fatten with anger. There’s the suggestion of a grim puppet show—de Quincey’s head lolling like a fallen Punch. There’s a rare moment of touch, electric when it happens, other moments of apparent adoration or deep suspicion that suggest a relationship dancing in and out of sync.

Composer Michael Toisuta’s score operates at another level, a reminder with its persistent pulse of time manufactured and multiplied. Inspired by Ligeti’s Symphonic Poem for 100 Metronomes (1962) this surround sound creation is enveloping and some of its more dramatic changes in pace sharply re-shape the mood of the performance. There’s no sense, however, that de Quincey and Snow perform to it; it’s simply there with them; its time is not theirs.

Embrace: guilt frame is a small, intense work by skilled performers in a tiny theatrical frame that enlarges both our sense of time and of how driven we are by our visual curiosity.

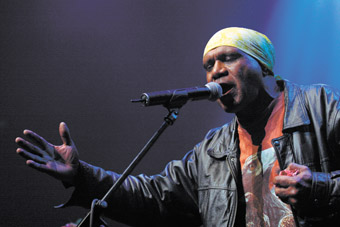

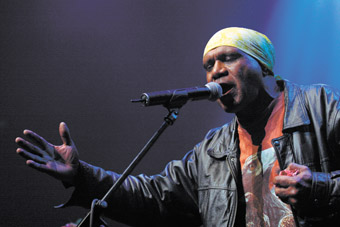

The Akram Khan-Sylvie Guillem duet, Sacred Monsters, is a very different experience, but it also has its roots in ancient Hindu culture and it too suspends our sense of time, if speed is more often its means than stillness. The work is very much framed by Khan’s story about himself as a young man wanting to play the god Krishna, but disappointed that he was too short and already losing his hair. He would find his way, he said, by finding the monster in himself, and that monster may well have been his meeting with modern western dance. By the end of Sacred Monsters he appears to have achieved the release and transcendance he has desired, but in a remarkable duet, not just his agonised solo—the god in many, not one.

There is therefore a very strong sense of release in this work. The initial image is of a still, chained Guillem, whom Khan soon frees. He then removes the long chains wrapped around his calves, hidden beneath his trousers, but heard jangling musically in the dance. Towards the work’s end, Guillem gently touches Khan’s bowed head as if investing him with godliness. Although Sacred Monsters largely comprises duets, each performer, while sitting, sipping water, wiping away sweat with a towel, intently watches the other’s solo. There’s a potent sense of mutual support and release.

There’s also a great sense of playfulness, of gentle mockery and brattishness in the dialogue. But the dancing expresses darker tensions between these divas (‘sacred monsters’ is the translation of the 19th century French term for ‘stars’) as they strike at each other, reeling from the impact before being actually hit, as if the work they had created together has been a battle. At separate points in Sacred Monsters, one falls prey to the other, flattened, left limp…ready to airily chat with us and move on. The informality is heightened by the musicians (providing another East-West dynamic) sitting on stage with the performers and the female singer moving around the dancers.

A critical point occurs when Khan sits upstage quietly uttering, “Is this right?”, “Just an experiment!”, as if querying and asserting his melding of ancient and modern traditions. Moving forward on his knees, torso low to the floor, almost abject, his delivery becomes more urgent. His right arm shoots out and withdraws. Suddenly he thrusts his body up, almost erect, suspended, before falling to the floor and moving even more urgently forward again reporting the action. It’s an astonishing and painful dance. And crucially it’s followed by the pivotal duet of Sacred Monsters where Guillem straddles Khan, hip to hip, face to face. She leans back and they become one, an eight-limbed god in a dance of astonishing strength, sensuality and passion, their hands flickering their own finely articulated dance. Krishna.

Khan and Guillem languidly mop the floor with their towels (it’s your sweat, she mocks), preparing for a final, very earthed celebratory dance. Sacred Monsters is a wonderful collaboration, a fine conjuction of styles, traditions and personalities. Guillem’s stories are less elemental than Khan’s, less revealing, but wry and witty, reinforcing the embracing casualness of the show’s chatty framework (audible, if not always, in a concert hall bedecked with extra curtaining to damp the resonance). Her dancing, however, is almost beyond description, long lined and fluent, capable of breathtaking moves, like the reverse flip where her feet seem to barely leave the ground one after the other, and the ease with which she meets the speed and weight of Khan’s lower-placed centre of gravity. Sacred Monsters is a work of reflection and cross-cultural kinship, movingly and bracingly performed with great passion and remarkable skill.

–

Sydney Theatre Company, Wharf2Loud, embrace: Guilt Frame, created and performed by Tess de Quincey and Peter Snow, original concept Tess de Quincey, set designers Russell Emerson, Steve Howarth, construction by erth, lighting designer Travis Hodgson, sound designer Michael Toisuta; Richard Wherrett Studio, Sydney Theatre, Feb 27-March 9

Sacred Monsters, artistic director, choreographer Akram Khan, dancers Akram Khan, additional chorography Lin Hwai Min for Guillem, Gauri Sharam Tripathi for Khan, composer Philip Shephard, lighting Mikki Kunttu, set design Shizuka Hariu, costumes Kei Ho; Concert Hall, Sydney Opera House

RealTime issue #84 April-May 2008 pg. 32

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

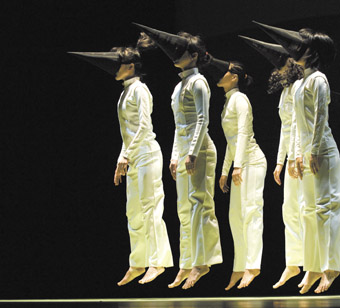

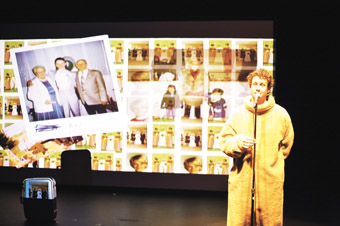

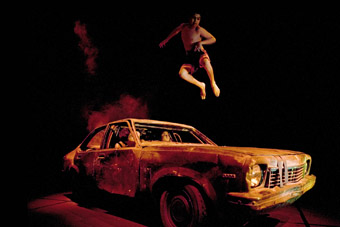

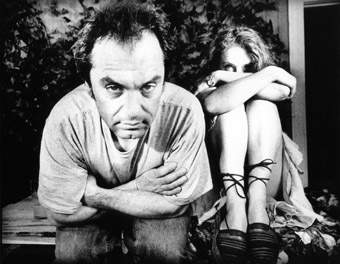

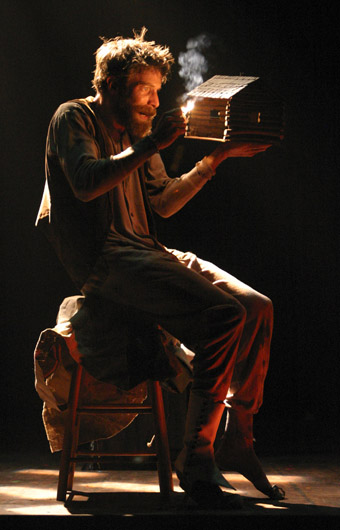

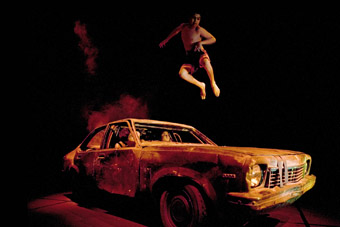

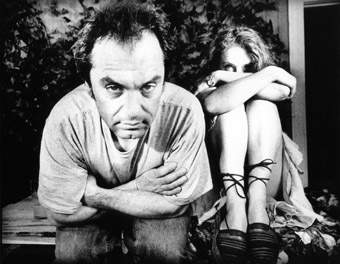

Dance Theatre ON, Ah Q

photo Choi YoungMo

Dance Theatre ON, Ah Q

THE DANCE PROGRAM OF THE 2008 SINGAPORE ARTS FESTIVAL IS PARTICULARLY STRONG, NOT LEAST IN THE WAY IT MORPHS INTO THE THEATRE PROGRAM WITH SOME FASCINATING HYBRID CREATIONS.

In Amjad, choreographer Édouard Lock and Canada’s La La La Human Steps challenge romantic ballet in the shape of Swan Lake and Sleeping Beauty. Lock was born in Morocco where Amjad, a name for children both male and female, means “greater glory”—the choice of title suggestive perhaps of Lock’s desire to transcend the inherent violence of gender divisions, not least in classical ballet. He requires of his company both ballet skills and hard-edged, fast contemporary dance.The multimedia set is by French-Canadian sculptor Armand Vaillancourt and the music mix comprises works by Gavin Bryars, David Lang, noise artist Blake Hargreaves and, of course, Tchaikovsky.

Romanian Edward Clug is the house choreographer and head of ballet at the Slovene National Theatre in Maribor, Slovenia’s second largest city. His Radio and Juliet is Romeo & Juliet performed to the music of Radiohead and tells the tragic tale in reverse. In another major work, The Architecture of Silence, Clug choreographs his company as fish-like dancers in virtual waters to contrasting requiems by Mozart and contemporary Polish composer Zbigniew Preisner (who scored films for director Krzystof Kieslowski). This epic production features 45 dancers, 80 singers and the Singapore Festival Orchestra.

In Japanese artist Nibroll’s No Direction, an exercise in miscommunication and an argument against homogenisation, eight performance artists “haphazardly inhabit a grid on stage, absorbing each other’s idiosyncracies and sporadic urges in a continuous interplay of music, movement, and visual images.” What began as an installation for Tokyo’s Metropolitan Museum of Photography has become a major performance work with the multimedia collective formed in 1997 by Yanaihara Mikuni. No Direction is dance and much more.

In Ah Q, South Korea’s Dance Theatre ON employs the Quixotic character from Luxun’s novel The True Story of Ah Q to explore the effects of ignorance and foolishness. Choreographer Hong Songyop’s productions are well known for their rich symbolism and surreal effects in their ventures into the psychological interior.

In the festival’s theatre program dance makes some intriguing appearances. In For all the Wrong Reasons, a collaboration between Belgium’s Victoria and the UK’s Manchester-based Contact, leading experimental theatre director Lies Pauwels addresses stupidity. The setting is a faded end-of-the-pier revue, the performace a set of dances, songs and confessional monologues replete with sheer silliness and moments of profundity (you can enjoy a delicate if bizarre dance segment on the festival website).

In Nine Hills One Valley, dancer-director-designer Ratan Thiyam and the Chorus Repertory Theatre of Manipur celebrate the traditional dance, theatre and other cultural forms of the remote regions of Manipur in eastern India, but they also lament the passing of these ancient and often interdisciplinary arts. Although not dance-based, Awaking, a new interdisciplinary work from Ong Keng Sen and TheatreWorks with contemporary Chinese composer Qu Xiao Song, looks to the literature, theatre and music of the past in very different cultures. Awaking addresses love through the works of Shakespeare and Ming Dynasty poet and playwright Tang Xian Zu, of Peony Pavilion fame. Both writers died in 1616. The performance features the Singapore Chinese Orchestra; the Musicians of the Globe led by Philip Pickett; and the kunqu opera actress Wei Chun Rong and her musicians from the Northern Kunqu Opera Theatre in Beijing.

The festival also includes Forward Moves, commissioned works from three female Singaporean choreographers: Ebelle Chong, Neo Hong Chin and Joavien Ng. Continuum from the Singapore Dance Theatre presents the Asian premieres of Evening by Graham Lustig (USA), The Grey Area by David Dawson (UK) and Glow-Stop by Jorma Elo (Finland).

On the experimental theatre front, Singaporean visual artist and filmmaker Ho Tzu Nyen [RT80, p54] and co-director Fran Borgia have been commissioned by the Singapore Arts Festival and Brussel’s Kunstenfestivaldesarts to create The King Lear Project: A Trilogy. The three productions, played over three days, work from well known critical essays on Shakespeare’s tragedy, realising them as audition, rehearsal and post-show discussion, worrying at the right way to stage the great work.

As for Australian content, in the 2008 Singapore Festival Geelong’s Back to Back Theatre continue on their quiet path to world domination with the remarkable Small Metal Objects. RT

The 2008 Singapore Arts Festival. May 23-June 22, www.singaporeartsfest.com

RealTime issue #84 April-May 2008 pg. 33

© RealTime ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

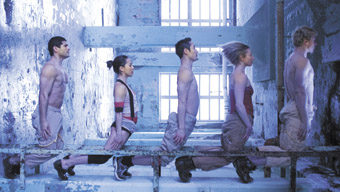

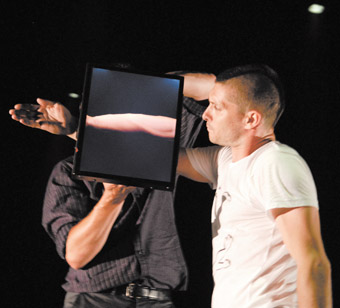

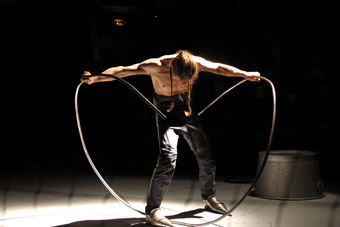

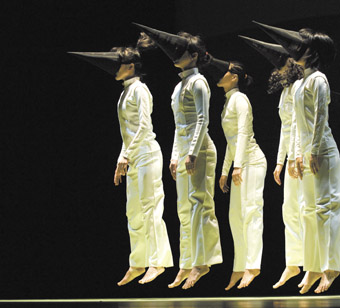

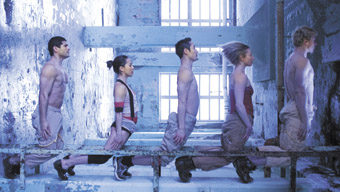

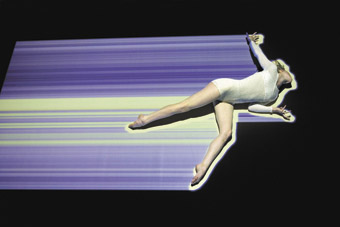

Pilobolus

photo John Kane, courtesy of the Joyce Theatre

Pilobolus

IN A 2005 ARTICLE IN THE NEW YORKER ON WHAT SHE SAW AS A SURREALIST REVIVAL IN DANCE IN DOWNTOWN NEW YORK, CRITIC JOAN ACOCELLA IDENTIFIED PILOBOLUS AS ONE OF THE PIONEERS OF THE MOVEMENT WHICH MORE RECENTLY HAD BEEN TAKEN UP BY CHOREOGRAPHERS LIKE TERE O’CONNOR AND FORMER MEMBERS OF HIS COMPANY INCLUDING UP AND COMING CHOREOGRAPHER/PUPPETEER CHRISTOPHER WILLIAMS. SHE EXAMINED CHUNKY MOVE’S TENSE DAVE, TOURING NEW YORK AT THE TIME, IN THE SAME SURREALIST LIGHT.

Taking its name from a sun-loving fungus, Pilobolus emerged in 1971 when a group of dance students at Dartmouth College interested in “a collaborative choreographic model and a unique weight-sharing attitude to partnering” decided to form a company. Pilobolus is still a deeply collaborative entity with three artistic directors and the company’s seven dancers all contributing to the repertoire. Merging dance and biology into an inventive and eloquent physical vocabulary, this is also a company with a mission “to use their organization and creative methodology to stimulate, educate and expand the audience for dance through innovation, collaboration and public service.”

Pilobolus is visiting Australia for the very first time in May, performing a five-work show in the hotbed of Adelaide Festival Centre’s variegated dance program, Pivot(al), including Day 2, set to the music of Brian Eno and Talking Heads which “captures the awe of evolution and the wonder of existence.” Let’s hope there’ll be time while they’re here for a little cross-pollination of ideas on artistic sustainability.

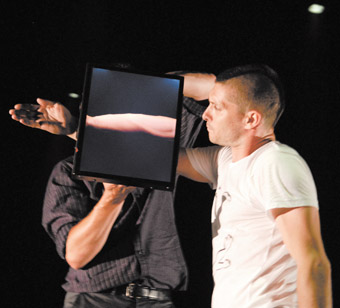

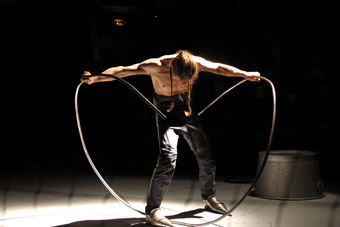

Speaking of survival, Dean Walsh is a highly accomplished Australian dancer/choreographer who has been evolving his own idiosyncratic body of work over a decade and, at the same time, performing with companies such as Australian Dance Theatre, DV8 Physical Theatre in the UK and No Apology Company in Amsterdam.

Dean Walsh’s Back From Front

photo Heidrun Löhr

Dean Walsh’s Back From Front

Walsh’s new work, Back From Front premiering at Performance Space in May, draws on stories from veterans of World War 2 through to the Iraq conflict. Walsh defines this as “a piece about the lingering impact of wartime experience on soldiers and their families—from the immediate challenges of re-adjusting to post-war life, to the continuing cycles of violence that can penetrate families for generations to come.”

Clearly referencing the territory of some of Walsh’s earlier, intimate solos, Back From Front is his first large-scale group work. With a strong cast and a team of production collaborators (including John Levey, Rolando Ramos, Simon Wise, Nikki Heywood) the work combines video imagery with lighting and movement.

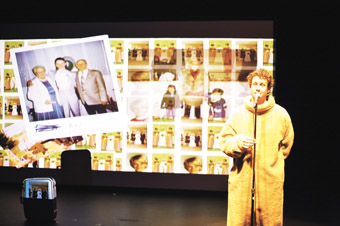

Elizabeth Ryan, Jane McKernan, Emma Saunders, The Fondue Set, No Success Like Failure

photo Irèn Skaarnes

Elizabeth Ryan, Jane McKernan, Emma Saunders, The Fondue Set, No Success Like Failure

Adaptation is what it’s all about for The Fondue Set (Elizabeth Ryan, Jane McKernan, Emma Saunders) and if their new work sounds a bit ‘under’ as they say on So You Think You Can Dance, it’s intentional. For a while now this talented trio has been performing serious experiments—taking dance apart and trying to put it back together in some semblance of order—while simultaneously masquerading as good time girls. In No Success Like Failure, their collaboration with the idiosyncratic UK choreographer Wendy Houstoun, they have distilled hours of serious experiment into an intriguing evening of performance in which they’ll be “lying, dying, singing, trying and trying again.” And as if that weren’t enough they also promise “motivational dancing, negative cheering, successful snoring, hypnotism, word bingo and more!”

Sara Black, Dance Like Your Old Man, Chunky Move

The highly adaptive hybridiser Chunky Move, working across dance, film and interactive media, is currently thriving with the international suucess of Glow and now an invitation to stage their Mortal Engine at the 2008 Edinburgh International Festival. In works like Singularity and I Want to Dance Better at Parties, the company has also been evolving a repertoire of choreographic works that intersect with everyday movement. In the film Dance Like Your Old Man, Gideon Obarzanek and Edwina Throsby’s joyous and thoughtful 10-minute dance documentary, six women do just that, proving once and for all the power of body memory. As they recall their moves, the women also remember the men who made them (in more ways than one). With this film the company has collected a couple more trophies, namely the 2008 ReelDance Award for Best Dance Documentary and Best Documentary at this year’s Flickerfest Short Film Festival. RT

–

Pivot(al), Pilobolus, Her Majesty’s Theatre, May 6-10, www.adelaidefestivalcentre.com.au; Dean Walsh, Back From Front, Performance Space at CarriageWorks. May 1-10, www.performancespace.com.au; Fondue Set, No Success Like Failure, The Studio, Sydney Opera House, June 4-8, www.sydneyoperahouse.com; Campbelltown Arts Centre, June 12-14 June; Arts House, North Melbourne Town Hall, August; Chunky Move, Dance Like Your Old Man, Reeldance 2008, www.reeldance.org.au; Chunky Move, Mortal Engine, Edinburgh Playhouse, 2008 Edinburgh International Festival, Aug 17-19

RealTime issue #84 April-May 2008 pg. 33

© RealTime; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Ningali Lawford-Wolf, Margaret Mills, Kelton Pell, Tony Briggs, Jimi Bani, Jandamarra

photo Gary Marsh

Ningali Lawford-Wolf, Margaret Mills, Kelton Pell, Tony Briggs, Jimi Bani, Jandamarra

AFTER A ROCKY PREMIERE, JANDAMARRA BECAME A SUPERB WORK OF EPIC THEATRE, AKIN TO NEIL ARMFIELD’S CHEERY SOUL (1993) OR CLOUDSTREET (1998). DIRECTOR TOM GUTTERIDGE ECHOED ARMFIELD BY FILLING THE WINGS WITH PARTIALLY VISIBLE INSTRUMENTS, WIND-MAKERS, AND OTHER THEATRICAL MACHINERY WITH WHICH THE OFFSTAGE ACTORS VOICED THE ACTION. WITH ELDERLY INDIGENOUS SINGER GEORGE BROOKING SEATED BEFORE A MICROPHONE, THIS GAVE A SENSE OF MEMORY, BREATH AND RITUAL TO THE WORK, BRINGING THE ACTORS, FORMS AND HISTORIES TO LIFE.

Zoe Atkinson’s design for Jandamarra consisted of cliff panels—parting to reveal a vulva crease into which the protagonist stalked—bounded below by a sandpit from which set elements emerged or into which they were planted (fires, trees, graves). Platforms atop enabled split level performance, languid Indigenous scenes floating above tense European exchanges. Also remarkable was how Atkinson’s crinkled surfaces, projections of translations and Indigenous animations turned the space into a worn chapbook onto which histories and dreams were screened.

Jandamarra tells the story of the eponymous Aboriginal resistance leader in the Kimberley region in the 1870s, focusing on his complicated standing with whites and his own people. Never formally initiated into his clan, Jandamarra was befriended by the sporadically ruthless Constable Richardson before killing him and leading the Bunuba people against the graziers. The Bunuba attributed Jandamarra’s prowess to his magical skills, redefining him from tribal outcast to a key figure in their mythos.

Steve Hawke’s script was compiled with the traditional owners and Jandamarra’s story is portrayed in environmental terms above those of race or war. Jandamarra becomes one who, even without initiation, could read the land’s pain and recognise those waterholes which neither Bunuba nor white should disturb. Eventually, Jandamarra claims he fought not to defend his people per se, but the land itself. Although subplots involve black-white relations—notably the awkward reconciliation between the placeless station-owner’s widow and Jandamarra’s mother—the play comes across as somehow apolitical, being more about issues of the natural rather than racial oppression and armed resistance. It’s hard to imagine depicting the Irish resistance to English farming after 1600 in similar terms, despite the significance of Indigenous land use to both.

This recasting of identity in spiritual terms also characterised Tero Saarinen’s Borrowed Light. The Finnish choreographer drew on that American modernist archetype the Puritan sect, the Shakers. Together with the Amish, the Shakers’ austerity in their much collected furniture and quilts was central to 20th century American aesthetics, influencing architects (Frank Lloyd Wright’s furnishings), composers (Aaron Copland’s Appalachian Spring, written for Martha Graham) and dancers (Doris Humphrey, Twyla Tharp and Graham all produced Shaker pieces). The dialectic between Protestant restraint and the ecstatic seizures of devotees to such 19th century US ‘campfire meetings’ fascinated choreographers from Mary Wigman to Ruth Saint-Denis. Despite the hostility of these sects to modernism (the Amish do not drive) and social norms (the Shakers are celibate), they were central to post-WWII America’s self-definition as a streamlined, modern, yet lyrical, nation.

Saarinen sets aside these national references but embraces a nostalgia for disciplines of physical and emotional frugality and the tragedy of their loss. Borrowed Light is a hymn for a lost idea of what modern art was. Amidst the sustained simplicity of a choir (the Boston Camerata) singing Shaker hymns, Saarinen’s dancers twist and sway in unison (recalling Wigman’s “choric dancing”) before succumbing to individual contortions and an emptying out of the body via tension and release.

Bodies begin as trapezoids, with wide stompy legs (emphasised by the men’s black robes and the women’s dresses) rising to a dynamic torso. This alternates with expansion of the chest outward with arms not just flung back but curled into neurotic filigrees. Saarinen’s work is dramatically classical in its precision and sculptural form, yet its grotesque details recall butoh. The design also echoes Euro-American modernists, notably Adolphe Appia and Edward Gordon Craig, who advocated tides of directional white light between rising stairs to create a hierarchical space for the individual to strive for his or her spiritual ascent. Bounding the space, these flights and levels (differentially tinted black, grey and white by Mikki Kunttu) become a parable for the dancers’ terrestrial embodiment and their eternal striving, through and of the body, to free themselves. As dancers collapse and drag themselves across the space, the insufficiency of modernist ecstasy—as well as its joy—is performed.

A different sensibility is found in the work of Chrissie Parrott and Jonathan Mustard. Each piece in their trilogy, Metadance in Resonant Light, includes projection: animated figures in Recording Angel and Metadance, computer code in Metadance, and noirish Expressionism alongside the black-bobbed women of Split. Film noir is the dominant style in the latter, a duet supported by video showing dancers silhouetted in doorways. Head shots also feature, with hair swirling about visages, obscuring personalities even as they are suggested. Split evokes a house of memory and angst, affectively placing it in a predigital realm. This is further enhanced through haunting, aged-sounding music by Set Fire To The Flames. Split is animated by doppelgangers—the women’s other selves, and their struggle against their own otherness; femme fatales of their own desire. While similar to In Absentia (1997) by Sandra Parker and Margie Medlin—another work evoking uneasy memories through projection—Parrott’s work is more dramatic, with suggestions of specific (if opaque) characters.

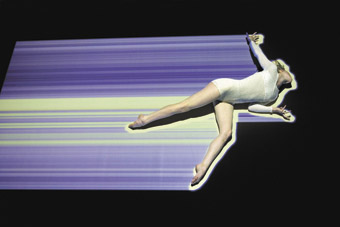

Metadance

photo Jon Green

Metadance

Metadance has four dancers within a sea of floating and spinning text which codes music and avatars. As with Merce Cunningham’s Biped (1999), Parrott uses the X-Y-Z coordinates so generated to devise the choreography. Nevertheless, the movement remains recognisably hers. Hidden amongst translucent screens bearing rows of letters and grids, dancers under spotlights mark a constrained area with taught precision and line. Full limb extensions are common. Although each body often crouches low with one leg moving out at 30 degrees under the hips while the other bears the weight, aggressive twists or bends are rare. The dance retains Parrott’s sense of lyric control and clarity. Mustard’s music is less characteristic, departing from his 1980s MIDI palette to create a weft of ringing metallic strikes echoing away eternally, radiophonic quotations (a French vaudeville song for the juggling interlude, complete with projected balls), shuddering percussive fields and whining tones.

Recording Angel is the most impressive of the trilogy, simplifying and extending Metadance. Dancer Joshua Mu perches, birdlike, head down, arms spread, barely visible under tints of blue, posed beside his virtual double. The separation between live performer and avatar is blurred, both defined by slight glows within an ill-defined space. The measured choreography also imparts a sculptural feel, challenging not only distinctions between body and projection but dance and installation. It is often hard to see the movement. This is combined with Martin Tellinga’s music, recorded so well that, even in stereo, it sounds like its windy sheets and angry shimmering textures are charging behind us. Beyond narrative, meaning, or choreographic or dramaturgical evolution, Angel is a durational, experiential piece, affectively holding spectators in a profoundly sensual yet indeterminate fashion. As such, it avoids clichés of oscillating between technological visions of Frankensteinian disaster or naïvely utopian transcendence, to suggest a state neither liberating nor oppressive, yet intensely affective.

Perth International Arts Festival 2008: Black Swan Theatre Company with Bunuba Films, Jandamarra, writer Steve Hawke, director Tom Gutteridge, associate director, performer Ningali Lawford-Wolf, musical director Paul Kelly, designer Zoe Atkinson, lighting Andrew Lake, projected animations Kaylene Marr, Clancie Shorter, performers: Margaret Mills, Jimi Bani, Geoff Kelso, Emmanuel Brown, Tony Briggs, George Brooking, Simon Clarke, Peter Docker, Danny Marr, Kelton Pell, Dennis Simmons, Kevin Spratt, Sandra Umbagai-Clarke, Perth Convention Centre, February 9–23; Tero Saarinen Company and the Boston Camerata, Borrowed Light, choreographer, performer Tero Saarinen, musical director Joel Cohen, design & lighting Mikki Kunttu, costumes Erika Turunen, sound Heikki Iso-Ahola, His Majesty’s Theatre, Feb 27–Mar 1; Metadance In Resonant Light, choreography Chrissie Parrott, lighting/projection Jonathan Mustard, performers Joshua Mu, Sharlene Campbell, Sally Blatchford, Jacqui Claus. PICA, February 14–21

RealTime issue #84 April-May 2008 pg. 34

© Jonathan Marshall; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Chris Ryan, Meredith Penman, Chekhov Re-cut: Platonov

photo Jeff Busby

Chris Ryan, Meredith Penman, Chekhov Re-cut: Platonov

THE ANXIETY OF INFLUENCE, TO HIJACK HAROLD BLOOM’S TERM, IS PROBABLY MOST EVIDENT WHEN IT BESETS AN EMERGING DIRECTOR. YOU KNOW THE SORT—THE YOUNG TURK WHO WANTS TO REINVENT THEATRE, BREAK THE MOULD, SHAKE OFF THE SHACKLES OF AN ARTFORM OSSIFIED INTO RIGID PREDICTABILITY. OFTEN THE RESULT IS A LAMENTABLE MESS THAT MERELY ENDS UP IMITATING OTHER REBELLIOUS THEATREMAKERS WITHOUT BEING CONSCIOUS OF THE TRADITION BEING FOLLOWED. SOMETIMES, THOUGH, THE DELICATE BALANCE BETWEEN AN ORIGINAL VISION AND AN AWARENESS OF HISTORICAL TRADITION MAKES FOR SOMETHING GENUINELY NEW AND EXCITING.

Matthew Lutton and Simon Stone are both 23-year-old directors who have arrived on the stage from different directions. Lutton studied in a now defunct cross-disciplinary program at WAAPA before going on to establish his own theatre company and working as an associate director with Black Swan. Stone, on the other hand, comes from an acting background—the VCA grad’s self-formed company The Hayloft Project features many of his old classmates. And though they evince very contrasting aesthetics, both directors are proving capable of rubbing shoulders with theatre veterans twice their years.

Marcus Graham, Alison Whyte, Barry Otto, Tartuffe

photo Jeff Busby

Marcus Graham, Alison Whyte, Barry Otto, Tartuffe

malthouse’s tartuffe

Lutton stepped in to direct Malthouse Theatre’s first 2008 production, Tartuffe, at (quite literally) the last minute. The assistant director was informed on the first day of rehearsals that Michael Kantor was handing over the reins in order to undergo medical treatment for a coronary irregularity. It’s testament enough to a certain amount of sheer gumption, I suppose, that Lutton didn’t baulk at the announcement but set to work. And though Kantor’s own artistic imprint is still visible in the final work, Lutton brings enough creative license to the piece to finally make it his own.

Tartuffe is freely adapted by Louise Fox after the Molière play of the same name. Where the original was a satirical swipe at the hypocrisy of organised religion and the greed of the aristocracy, Fox’s version is a bawdy, carnivalesque skewering of contemporary Australian mores and misdemeanours. Marcus Graham plays the titular holy roller who infiltrates a wealthy, soulless Toorak family and profits from their moral bankruptcy and desire for the kind of spiritual satisfaction only money can buy. Barry Otto and Alison Whyte are the heads of the vacuous clan, and this trio makes up the central dynamic of the piece.

Lutton’s version pushes the comedy to suitably manic extremes. Like any good sit-com there’s rarely a line that isn’t some kind of gag or a moment without some physical foolery. He makes the most of a lavish set, complete with a long lap-pool, three-level balcony edifice and numerous trapdoors. But where a lesser work would simply devolve into zany clowning and frothy farce, this Tartuffe outdoes itself in a final directorial choice near the work’s end. In Molière’s original, the sudden, improbable intervention of the King neatly resolves the tale. Translating this into a more interesting contemporary parallel was always going to be difficult, but Lutton’s decision is a stroke of brilliance. Where much of the production is an hysterically amplified take on the real world of today, Lutton’s Tartuffe climaxes with the hilarious entrance of Jesus in robes and beard, arriving to set all aright. Rather than undoing the cop-out of Molière’s deus ex machina ending, Lutton turns it up a notch to go beyond satire into something approaching meta-theatre, exposing its own internal cracks as much as those of the flawed characters it has so far ridiculed.

hayloft’s platonov

Simon Stone’s Chekhov Re-cut: Platonov takes the early work by the canonical playwright and treats it with the irreverence one would expect from an emerging talent. This is only Stone’s second production—the first, Spring Awakening (to be seen in June at Belvoir Street in Sydney), was an equally riveting work, and Platonov continues his trajectory. It cuts and shuffles Chekhov’s sprawling five-hour play to less than half that. It updates the setting, to a point, to lend it both a contemporary relevancy and a generous respect for its source. And, visually, it’s a beautiful gift to its audience.

Platonov is a liberal misanthrope, an existentially despairing tragic who turns his bleak desolation on the humans around him. Numerous affairs and betrayals seem to entertain his love of power games, but when the precarious house of cards he gradually builds brings about his ruin the audience must ask whether this self-destruction was in some way willed. He’s certainly not a sympathetic figure at any turn, but he is a fascinating one.

In Stone’s hands Platonov, like Spring Awakening, is very much an actor’s piece. The performers are given full rein to explore and embellish characters with gusto, and each proves more than capable. There’s plenty of stage business making full use of the space, but this adds a tactile dynamism and energy to the work rather than appearing contrived or unnecessary. With the exception of a superfluous second-half opening in which the feverish Platonov is beset by a ghostly chorus of his peers, the production aims for heightened realism instead of heavy-handed symbolism or obvious directorial intrusion. Most encouraging of all, it’s a realism that meshes perfectly with theatricality, too often seen as exclusive opposites.

Evan Grainger’s set is a sure contender for a swag of accolades. The entire playing space is flooded with black, rippling water fringed by shattered and burnt walls; piles of mouldy books and decaying antique furniture jut from the water like lilies. A subtle lighting design creates a warm and cloying sense of brooding intimacy which shimmers as the performers wade, splash or retreat from the pool.

Simon Stone, like Matthew Lutton, displays a powerful ability to reinvent an old work, making that reinvention the point of the exercise. Both bring an understanding of and respect toward their respective sources while remaining unafraid to depart from them in order to produce a superior work. Are you paying attention, class?

Malthouse Theatre, Tartuffe, writer Molière, adaptation Louise Fox, director Matthew Lutton, performers Laura Brent, Marcus Graham, Francis Greenslade, Peter Houghton, Rebecca Massey, Barry Otto, Ezekiel Ox, Luke Ryan, Alison Whyte, designer Anna Tregloan, lighting designer Paul Jackson, composer Peter Farnan; CUB Malthouse, Feb 15-Mar 8; The Hayloft Project, Chekhov Re-cut: Platonov, writer Anton Chekhov, adaptation, direction Simon Stone, performers Jessamy Dyer, Amanda Falson, Angus Grant, Adrian Mulraney, Eryn-Jean Norvill, Meredith Penman, Chris Ryan, Simon Stone, designer Evan Granger, lighting design Danny Pettingill, sound Jared Lewis; The Hayloft, Footscray, Melbourne Feb 27-Mar 16

RealTime issue #84 April-May 2008 pg. 36

© John Bailey; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Alex Grady, Matthew Prest, The Whale Chorus

JANIE GIBSON’S THE WHALE CHORUS IS MYSTERIOUS AND CHAOTIC, A DREAM MUTATING INTO NIGHTMARE AMBIGUOUSLY HOSTED BY A YOUNG WOMAN (GIBSON) IN DARK WEIMAR CABARET PERSONA, ACCENT AND ALL, A SET OF TRULY EERIE TALES AND, IN THE CLIMAX, SPECTACULARLY STAGED SUPERNATURAL POWERS OUT OF THE MATRIX AND THE RING CYCLE.

Two competitive young men (Matthew Prest, Alex Grady) prance about like centaurs, revealing their love-lorn inner states via intensely delivered pop songs; two women (Phoebe Torzillo, XX) engage in more gnomic behaviour, sometimes gratingly cute but also tinged with dark prophecy.

Like the vigorous, ambitious ensemble dancing, the production constantly threatens to fall apart. Save for Gibson’s disturbing, blackly comic tales the writing is thin, the other female roles limited and the production’s grand symbolism opaque.

As a director Gibson is courageous, her vision reminiscent of Melbourne playwright Lally Katz’s anarchic theatrical magic but, unfortunately, there’s little sense of The Whale Chorus being through-written. Nevertheless the production proved oddly memorable. Alex Grady is a subtle presence, Gibson has a magnetic, quiet intensity, and Prest a vibrant nervous energy. Above all it was exhilarating to see a young ensemble performing with total commitment.

The Whale Chorus, director Janie Gibson, performers Alex Grady, Matthew Prest, Phoebe Torzillo, XX, Janie Gibson, sound James Brown, costumes Lucy Thornett, magic maker Michaela Gleave, lighting designer Frank Malnoo; PACT Youth Theatre, Sydney, Feb 28-March 9

RealTime issue #84 April-May 2008 pg. 36

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

REACH INTO YOUR POCKET AND BRING OUT YOUR WALLET. YOU DON’T RECOGNISE THIS WALLET. REACH INTO YOUR BAG AND BRING OUT YOUR MOBILE PHONE. YOU DON’T RECOGNISE THIS MOBILE PHONE. LOOK AT THE NAME ON THE PIECE OF PAPER YOU’RE HOLDING. YOU DON’T RECOGNISE THIS NAME. IS THIS A NIGHTMARE OF LOSS OR A FANTASY OF FREEDOM? EITHER WAY, IT WAS THE EXPERIENCE OF PARTICIPANTS IN LIFE EXCHANGE, A PROJECT ORCHESTRATED BY BERLIN-BASED ARTISTS WOOLOO PRODUCTIONS.

Between October 31 and November 6, 2007, 10 people were sent blinking into the streets of New York with just a stranger’s possessions to guide them. Martin Rosengaard and Sixten Kai Nielsen, of Wooloo Productions, interviewed participants who were each willing to swap lives with a stranger and matched them into pairs. The longest exchange took one week; the shortest was 24 hours.

Surely you’d have to be crazy to trust a stranger with your house keys, your credit card, your job, your relationships? Participants didn’t just swap material possessions but also met each other’s lovers, worked in each other’s jobs and (although not in all cases) lived in each other’s homes.

For some, this demand for trust might seem like a nightmarish risk, but Rosengaard says it is one of the project’s strengths. Particularly in America, he says, there is a “performance of distrust” carried out by the state, which encourages people to be suspicious of each other’s motives and exploits an inherent conservatism of fear. In contrast, Life Exchange invited a very un-public display of trust and openness.

In fact, the relationship between two strangers was not the central experience of Life Exchange—after all, they didn’t really meet. One participant, occupying the life of Guilio d’Agostino for a day, found himself flirting with a woman on the subway. Twenty-four hours later he had returned to his identity of Ektoras Binikos, who is gay. Obviously, Life Exchange did not affect Ektoras’ sexuality, but it did encourage him to do something outside his normal experience. Crucially, this change in behaviour was not because Ektoras stole Guilio’s identity, but because for a time he was bereft of his own.

Participants in Life Exchange knew nothing about their ‘new life’ until the moment they inhabited it; and for each piece of someone else’s persona they acquired they lost the corresponding accoutrement of their own—their own mobile phone, their own best friend, their own routine. The process must have seemed more like a loss than an acquisition. In this light, the man who flirted with a woman on that November morning was not Guilio d’Agostino (who knows if he flirts with women on the subway?) or even a performance of ‘Guilio d’Agostino’ (having never met him, how could Ektoras know how to perform?). Instead, it was an anti-performance of Ektoras Binikos—a man whose codes and imperatives of behaviour had suddenly been stripped away.

In a city that was playing host, at the same time, to the dead-eyed ‘re-enactments’ of Alan Kaprow’s Happenings [RT 83, p17] , this seemed like a breath of fresh air. Kaprow wrote scores to encourage people to meditate on the experience of living and to blur the definitions of art and life. But, a year after Kaprow’s death, these re-enactments, watched in a packed warehouse in Long Island, were like the hammy cousins of an art historical moment that was never meant to be played to an audience. In contrast, Life Exchange seemed to promise a very real experience—the “sensory becoming” that Deleuze and Guattari describe as the true effect of a work of art.

But while Binikos found the experience of Life Exchange liberating, the project encouraged self-reflection in a very controlled way. The precedent for Wooloo Productions’ 2007 Life Exchange is Nancy Weber’s Life Swap (1974, written up in a book published by Dial Press in the same year), in which Weber changed lives with another woman. Her swap was precipitated by months of discussion, note-taking and written instructions between the women, but it ended badly with each accusing the other of dishonesty and misrepresentation. Life Exchange, however, removed the possibility of any such accusations, because it took responsibility for the project away from the people taking part.

It was Wooloo Productions (rather than any of the people whose lives were exchanged) who provided legal documents and disclaimers; Wooloo Productions who carried out interviews and made matches; and Wooloo Productions who conducted a Life Exchange Ritual at the beginning of each swap. This meant that ‘exchangers’ were free to concentrate on their personal experiences. And, unlike the earlier project, they could never accuse each other of sabotage, because they didn’t own the processes that governed their behaviour. These processes were owned and issued, instead, by Wooloo Productions.

In other words, Wooloo Productions institutionalised Weber’s model. If Weber’s Life Swap was carried out like two women bartering in a market, then Wooloo’s exchange was more like people ticking ‘yes’ to the terms and conditions on a website. This overt mediation concentrated the experience on each participating individual, but it also rendered them strangely passive in the process. Even when exchanges ended badly—as did one between Jane Harris and ‘Joanna’, cut short after just a few hours—the participants did not blame each other but the institution that had led them there. “Just be forewarned”, says Harris about Wooloo Productions, “they don’t seem to know what they’re doing” (www.artnet.com).

It is this relationship of trust between individual and institution that lies at the centre of Life Exchange. Harris’ disappointment with the project reveals her desire to trust the institution—if ‘they’ don’t know what they’re doing, then who does?

In fact, during Life Exchange Wooloo Productions acted just like the big cultural institutions that govern our lives—what Althusser calls institutional state apparatuses. This similarity even extends to the “performance of distrust” Wooloo’s Rosengaard identified in US federal policy. Like the government’s performance, Life Exchange relied on an entity whose power is hinted at but never explained; participants were even blindfolded during the Life Exchange Ritual that began each swap to reinforce this sense of mysterious power. And, like government performance, Life Exchange demanded casual complicity from its public.

Was Jane Harris right to have doubts about Wooloo Productions? The institutional façade that the organisation erected was flimsy at best. The Life Exchange Ritual, for example, which featured candles and New Age music, was an empty, generic scene such as might appear, Rosengaard says, if you googled the world ‘ritual.’ And unlike US government policy, Life Exchange did not exploit conservatism. Instead, it centred on unpredictability, stripping individuals of their symbols and then leaving them to their own devices.

Life Exchange created a dream of freedom and a nightmare of loss at the same time. It gave its participants liberty from identity, agency and expectations. But in return it enacted a loss of identity, freedom and agency. Creating a mask that borrowed from the familiar processes of big cultural institutions, Wooloo Productions suggested that liberty can only come from the comforting arms of an institution. The question, then, is which institution do you choose? And which liberty?

Wooloo Productions, Life Exchange, New York, Oct 31-Nov 6, 2007

RealTime issue #84 April-May 2008 pg. 37

© Mary Paterson; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Erth dinosaur, designers Steve Howarth, Bryony Anderson , Chris Covich, Phil Downing, Clalre Milledge, Ferdinand Mana

photo Prudence Upton

Erth dinosaur, designers Steve Howarth, Bryony Anderson , Chris Covich, Phil Downing, Clalre Milledge, Ferdinand Mana

TWO DINOSAURS ROAMED THE VAST FOYER FOR THE JOINT LAUNCH OF THE 2008 CARRIAGEWORKS AND PERFORMANCE SPACE PROGRAMS, A PALPABLY EXCITING MOMENT AFTER THE 2007 SETTLING IN FOR BOTH ORGANISATIONS. THE AMIABLE BEASTS ARE UTTERLY CONVINCING CREATIONS BY ERTH PHYSICAL & VISUAL THEATRE INC, ONE OF THE COMPANIES RESIDENT AT CARRIAGEWORKS.

Like big, slow puppies, the dinosaurs mingled with the large, if surprised crowd, making a brief appearance before leaving for Los Angeles—they were commissioned by the Los Angeles County Natural History Museum. A proud Scott Wright from Erth declares that the creatures are anatomically correct but is at pains to point out, because they’re often asked about it, that the company has nothing to do with the multi-million dollar Walking with Dinosaurs show. Wright is emphatic, these are human-driven body puppets; look, no animatronics!

Festivals at CarriageWorks in 2008 include Platform 1 Hip Hop Festival, Sydney Writers’ Festival, the return of Underbelly public arts lab + festival (after its successful celebration of underground and emerging artists in 2007), the Sydney Children’s Festival and the second Destination Film Festival, curated by Megan Spencer. Synergy Percussion will present two concerts (one of Reich and Xenakis compositions, the other with Swiss drummer Fritz Hauser and sound designer Bob Scott) across the year, and Sydney Dance Company three productions with new works by Meryl Tankard, London based choreographer Rafael Bonachela and New York-based Aszure Barton. The year’s program also includes young experimental theatre company The Rabble in Salome and newly resident company Force Majeure in a return season of their Sydney and Adelaide Festival hit, The Age I’m in.

The Performance Space program is well under way. Soon the space presents Experimenta Playground [RT 81, p34], the biennial of media art, ReelDance Festival 2008 [see page 22], Back from Front, a major new dance work from Dean Walsh [p33] and Branch Nebula’s Paradise City [on its Mobile States national tour after its trip to South America]. In the winter program there’s a new dance work, Ground Up, from Bernadette Walong, inspired by the Rainbow Serpent, the Live Festival of works in development with the special appearance of London’s Pacitti Company, and a life-sized house created by a Matthieu Gallois as part of an installation program titled Makeshift, Suspended House, and Habits & Habitat.

Visual and sound artists David Haines and Joyce Hinterding will present their large-scale sculptural installation, Anechoic Chamber, in the Performance Space’s Spring program. The chamber will be properly anechoic—totally sound-proof and devoid of resonance. Townsville’s Dance North, after their successful collaboration with Splinter Group on the acclaimed Road Kill, will perform Underground (set on a subway in rush hour and slipping into a dream world) and Tess de Quincey [p32] her new work, Triptych, focusing on air, electricity and water and using large projections wrapped around the audience.

It’s a big year for CarriageWorks and Performance Space, offering programs which will maintain continuity, sustain innovation and make the future. The venue will be busier than ever, the new Anna Schwartz Gallery (to open with a major Mike Parr exhibition later in the year) will add yet another dimension to this new home to the contemporary arts. RT

www.cariageworks.com.au

www.performancespace.com.au

RealTime issue #84 April-May 2008 pg. 37

© RealTime ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Scotia Monkivitch, A Mouthful of Pins

photo Bev Jensen

Scotia Monkivitch, A Mouthful of Pins

THE NEST’S A MOUTHFUL OF PINS ATTEMPTS TO WRING ENDURING BEAUTY FROM THE TERRIBLE EXPERIENCE OF MELANCHOLIA OR DEPRESSION. KOKO (LEAH MERCER), AS OUR CONTEMPORARY, CARRIES “THE TORN PAGES OF HER STORY UP THE STAIRS OF AN OLD VICTORIAN APARTMENT BUILDING IN BRISBANE.” HERE SHE MEETS, OR IMAGINES SHE MEETS, TWO DIFFERENT HISTORICAL CHARACTERS, ONE AN EXTRAORDINARY REGENCY PERSONAGE BASED ON THE LETTERS OF JANE AUSTEN (AOLE T MILLER), AND THE OTHER A 50S HITCHCOCK BLONDE/HOUSEWIFE (SCOTIA MONKIVITCH). THERE IS A SETTEE AND A COLLECTION OF BIRD-LIKE COMMEDIA MASKS SUGGESTING THAT THEY ARE KOKO’S ADOPTED PERSONAS.

Madness is in the air. Nature is outside (flitting bird images) and projected titles record the remorseless succession of days in a series of cryptic notes and quotes: “‘There isn’t a Monday that would not cede its place to Tuesday.’ Anton Chekhov.” Live music (piano and violin), song, visual images, the dislocation of narrative units along with highly suggestive symbolic actions invest the piece with deliberate ambiguity. These strands came together most movingly in an extended piece played by a violinist over the recumbent, temporarily enervated and silent figures on stage. At this point it became evident, looking at it from a Lacanian perspective, that “The things we are dealing with…are things in so far as they are silent. And silent things are not quite the same as things that have no connection with words.” At the very beginning, in order to define the space, words on paper are laid out in a circular pattern blank side up so that they are ritually obscured from sight. We are not dealing with a clinical case. What is of primary importance is, in Julia Kristeva’s terms, the rhythms and alliterations of semiotic processes which, combined with the polyvalence of sign and symbol, “unsettles naming.” In the best sense, The Nest’s project is grandiose: attempting to capture the sublime in art.

As a writer, Leah Mercer is obviously conversant with psychoanalytical concerns but (rightly) stops short of fully articulating them: “Sadness is a memory of something long ago, can you call it a memory if you can’t remember it? A memory of something I cannot quite recall, the unremembered, the unrememberable sitting there high in my chest.” Her adoption of a depressed person’s monotonous and rhythmically repetitive delivery stems from this sadness lodged in her chest, sentences that, as Kristeva describes them, “come to a standstill.” I admired what amounted to a sustained virtuosic performance of its kind, but questioned whether Mercer’s affects contributed to theatrical efficacy. At times it seemed that the beating heart of the production had also come to a standstill, and surely the beautiful words of her last song—“Singing is breathing, is thinking, is speaking…”—demanded soaring to the heights? The depth of Koko’s situation is encountered through an act of fellatio which, on the surface, seemed to imply for some in the audience a history of sexual abuse. I read it, to the contrary, as a rupture of Koko’s hermetic world. Abruptly propelled into a different space, she finds resources of compassion and forgiveness that lead her to intervene in the ritual self-harm perpetrated by the Monkivitch character.

The choice of a male to play the Jane Austen part had pluses and minuses. It allowed for Koko’s repudiation of the phallic mother in the fellatio scene but didn’t necessarily enable her to resist the circuits of patriarchal exchange within which they function as objects. But I’m afraid that Miller’s drag queen performance militated against any elaboration of this idea. This was a pity, though this richly written role has sent me off in search of Jane Austen’s letters.

Scotia Monkivitch’s hard boiled but vulnerable Hollywood diva displayed symptoms of hysteria rather than melancholia. She points this out herself when she expresses the view that Freud would have labeled all three characters hysterics. In this respect, she also appeared to be less passive than the others—the literal metaphor for her character being that the shoe doesn’t seem to fit. Monkivitch is also the most engaging performer, combining a clown’s panache with acid one-liners that cut (!) through Koko’s unremitting gravitas and the high-handed style of Miller’s Jane Austen. Her eruptive dancing with the latter evokes the sheer possibility of jouissance, of an active resistance. She is a fusion of acting and acting out. Unable to utter the void, she too is “growing a book/ tending slender pages of skin/ to replace you” (her ex-lover). Her brashness only renders her self-laceration more painful to the audience; attacking her own thighs with a knife in semi-seductive fashion negates all concepts of desire. Her most gorgeous and revealing theatrical moment occurs, however, when she comically stuffs her mouth with marshmallows. This action was prefigured when she insouciantly demanded her share of opium drops medically prescribed for her Regency counterpart.

Monkivitch’s excessively mimed bulimia is likewise prescriptive but also contains the idea of a not wholly successful attempt at self-determination. Thus there is unresolved irony as the lights fade after Koko’s apparently triumphal song. Monkivitch crouches like a cornered animal confronting the audience with her steely determination to remain hard boiled (thus untamable), at any price, unless the future manifests the kind of social revolution that legitimately grants women autonomy as subjects. There was much to admire about this brave and ambitious piece of contemporary performance despite a demonstrable need for reworking.

A Mouthful of Pins, writer Leah Mercer; director Margi Brown Ash, performers, Aole T Miller, Leah Mercer, Scotia Monkivitch, visual artist Jaqui Vial, production designer Bev Jensen, lighting designer Simon Johnson, music composed & performed by George Valenti and Moslo, songs & soundscape by Reilly Smethurst; Brisbane Powerhouse, Feb 14-16

RealTime issue #84 April-May 2008 pg. 38

© Douglas Leonard; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Tenderness: Ugly

photo Marg Horwell

Tenderness: Ugly

THE FIRST DETAILS I NOTICE UPON ENTERING THE PERFORMANCE SPACE AT 45 DOWNSTAIRS ARE LABELS CONTAINING KIDS’ NAMES ON CARDBOARD BOXES STACKED 10 DEEP THAT TOTTER TOWARD THE CEILING. IN PLATFORM YOUTH THEATRE’S DEPICTION OF THE COLLISION BETWEEN ADOLESCENT DREAMS, HORMONE PUMPED DESIRE AND THE DULL THROB OF ADULT LIFE, GOOD KIDS EXPECTED TO REACH GREAT HEIGHTS WILL SPIN OUT, AND COME CRASHING TO THE GROUND.

Tenderness, created from reseach with young people from Melbourne’s northern suburbs, consists of two plays residing at opposing ends of the gender equation, but both tell a similar tale. In Ugly by Christos Tsiolkas, Slim drops out of school, realising it has no place for him, nor he for it, in his dream of becoming a prizefighter. In this righteous rush of blood he fails to realise that the relationships formed in the schoolyard will continue to permeate his young life. In Slut by Patricia Cornelius, free thinking Lolita fucks everything that moves, instinctively responding to a diffuse sexuality that is at once admirable in its honest expression of unconditional love, but will be judged by her schoolyard peers as the immoral behaviour of a nymphomaniac.

Slim loves his girlfriend Sil with a vengeance. But his recently acquired lifestyle of dropping eccies and planting the porpoise no longer adheres to Sil’s father’s career-directed intentions for his daughter. Frustrated, Slim fractures the skull of a taxi driver and is set to suffer the consequences. Conversely, Lolita is pack-raped at a party by a conga line of quivering phalluses, and is only ever capable of maintaining destructive relationships characterised by violence and self-abuse. Like the theatre itself, it is during moments of transition between two worlds that Slim and Lolita experience the helplessness derived from standing up for your beliefs in a world that couldn’t care less. This irony synthesises the two plays, Slut and Ugly, into the one performance, Tenderness.

The grand finale is a striking suggestion of the possibilities of theatre as installation, and an underlining of this show’s curious moral code. Cardboard boxes are bustled away, revealing a split level glass case. Slim, naked and sexually shamed, sits crouched in what might be a prison cell. Above, Lolita’s suspended form is frozen in a sustained and terrified scream. Combined, this iconography presents as an image of the Crucifixion, and even though such a compelling visual statement must have proved irresistible to its creators, it struck me as an affirmation of the same Christian morality which has prompted Slim and Lolita’s sad decline. That is, until my sight is drawn towards blind performer Maysa Abouzeid and the collapsible cane she has carried throughout her performance, reminding me of a line from a Judith Wright poem, of a “Blind head butting in the dark…” Abouzeid’s presence suggests a less sanctimonious metaphor for the invisible terror arising out of adolescence, and a curt reminder of what the theatre is really about. Acts of courage in the face of enormous adversity, performed by communities not crying out for God, just simple moments of tenderness.

Platform Youth Theatre, Tenderness: Ugly, writer Christos Tsiolkas, Slut, writer Patricia Cornelius, director Nadja Kostich, performers Luke Fraser, Camille Lopez, Anastasia Babboussouras, Chloe Boreham, Maysa Abouzeid, designer Marg Horwell, lighting, Richard Vabre, sound Kelly Ryal, choreography Tony Yap; 45 downstairs, Melbourne, March 7-15

RealTime issue #84 April-May 2008 pg. 38

© Tony Reck; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Victoria Spence, Quick & Dirty

photo George Voulgaropoulos

Victoria Spence, Quick & Dirty

OUR HOST CANDY (VICTORIA SPENCE) DESCENDS THE STEEP AISLE, GREETED BY GREAT APPLAUSE. SHE’S “EMERGING FROM 12 LONG YEARS” THAT HAS INVOLVED SOME “DEEP UNDERCOVER WORK CALLED MOTHERHOOD.” BUT NOW SHE’S BACK. IT’S BEEN NINE YEARS SINCE TABOO PARLOUR, ITSELF A SUCCESSOR TO THE LEGENDARY CLUB BENT, APPEARED DURING MARDI GRAS AT PERFORMANCE SPACE, AND FINALLY QUICK AND DIRTY HAS ARRIVED TO FILL THE VOID.

With public acknowledgment of the collective responsibility of Australians for the past now firmly embedded in the national zeitgeist, Spence fittingly acknowledges the traditional Indigenous owners of the land on which tonight’s performance takes place. As she does so, she points also to the struggles for recognition of queer identities, thus framing Quick and Dirty as a gathering of disparate tribes who “continue to weave stories of love, respect, and resilience.” Her opening address received an enthusiastic cheer from the capacity crowd, and established the event as part remembrance, part celebration and part community affirmation all wrapped up within two sprawling nights of performance from a truly diverse range of queer-identified artists.

Each night’s program began with the amiably anarchic foyer carnival of Biffo’s Blow Up Bonanza, featuring an inflatable peepshow and various sideshow acts competing with loud audience chatter. More contemplative in tone were the concurrent durational performances. On Friday, Fiona McGregor’s Borne saw the artist laid out in a coffin, her naked body covered by layers of small gifts that the audience was invited to take. The quiet reverence of the installation was a welcome contrast to the chaos outside, but the effect was somewhat ruined by front of house staff persistently reminding audience members who chose to linger that this was a “durational piece”, and that once we’d taken our gift (a neatly wrapped packet of seeds), we should take our (quiet) conversations back outside. Saturday saw the exquisite intimacy of Sarah-Jane Norman’s Songs of Rapture and Torture (#1: Surabaya Johnny). After a long wait to be singly admitted, I entered to find Norman sitting naked, blindfolded and elaborately bound to a chair, singing huskily in German into a microphone dangling from the ceiling. Clearly, I’d arrived in the middle of some ordeal. After about five mesmerising and strangely anxious minutes, the door opened and I was politely ushered out. Norman continued to sing, lost in a private world of loss, pain and resignation. Despite the brief encounter, the powerful image lingered.

Gwenda & Guido, Quick & Dirty

photo George Voulgaropoulos

Gwenda & Guido, Quick & Dirty

Friday’s in-theatre acts included Trash Vaudeville’s restaging of his 1999 one-off Fool’s Gold using his original video animations. As the images progress he tries to remember what the piece was about, throwing himself from one pose to another, never seeming to recall what happens next. It’s an amusing, if rambling, exercise in media and memory, pointing clearly to the failures of both, but still managing to maintain its sense of humour even as the performance falls apart. This followed the amazing, crimson Chewbacca-esque creature and giant lolly-strewn stage of Buzz’s A Cavity Calamity, which unfortunately failed to provide much interest beyond its extravagant costuming. In The Invisible Woman from Outer Space, Glitta Supernova and Sex Intents presented a cosmic, ultraviolet strip tease, with the performer’s body disappearing as her fluorescent clothes flew away, seemingly of their own accord, culminating in a tiny rocket ship blasting off from her arse. Topping this, the highlight of the night was Gwenda and Guido’s White Heading, an outrageously bizarre Elvis-themed, whip cracking, cream-spraying, cake-eating, candle-inserting romp—sexy, funny and just plain wrong.

Saturday’s program was equally eclectic but far stronger overall. Wife’s Untitled began with a literally unravelling striptease, as a cunningly designed garment fell away forming a single thread. The piece ended with the viscerally discomforting removal of another thread, this time one stitched into the performer’s chest and examined in extreme close-up on video. Matt Hornby, Matt Stegh and Tristan Coumbe’s The Axis of Evil spectacularly queered the War on Iraq with production values to die for—breathtaking costume changes complete with decorated erect rocket penises, thrilling deathly dance routines, and satanic cameos. But the night belonged to The King Pins, whose Mystic Rehab was surely the ultimate in lip-syncing drag performance—performed with dazzling skill and energy, imaginative musical montage and stunningly excessive costumes that combined to produce a jaw-droppingly hilarious spectacle to send us all home wanting much much more. Let’s hope that we don’t have to wait another nine years for Quick and Dirty 2!

Performance Space, Sydney Gay & Lesbian Mardi Gras 2008: Quick and Dirty, coordinator Victoria Spence, lighting designer Clytie Smith, producer Fiona Winning, CarriageWorks; Sydney, Feb 22-23

RealTime issue #84 April-May 2008 pg. 39

© David Williams; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

A LARGE SCREEN UPSTAGE DISPLAYS A SILENT SKY, CLOUDS SKIMMING BELOW, THE COLOUR LIKE THE “BLUE SCREEN OF DEATH” THAT COMPUTERS DISPLAY BEFORE CRASHING. AS CHIKA HONDA: A DOCUMENTARY PERFORMANCE UNFOLDS IT BECOMES INCREASINGLY CLEAR THAT THIS COLOUR IS UNCANNILY APT, FOR THE ARREST, PROSECUTION AND INCARCERATION OF HONDA IS THE STORY OF A SYSTEM MALFUNCTIONING AND A LIFE CRASHING AS A RESULT.

The eponymous Chika, a Japanese tourist who was jailed for over a decade for allegedly importing heroin into Australia, emerges through a collage of images and interviews, live music and movement. Most of the images are stills taken by the show’s producer, photographer and narrator Mayu Kanamori, who regularly visited Honda during her imprisonment and who sits on a stool in front of a microphone for the duration of the performance. Other images include archival footage of the initial police interview and media coverage of the court case. Supplementing Kanamori’s verbal and visual narration are the recorded voices of Honda herself as well as her various supporters. When words fail, Tom Fitzgerald’s evocative music and Yumi Umiumare’s dramatic movement take over; together they gesture towards an angst that lies beyond language.

The storytelling is simple and effective, though perhaps not as self-revealing or self-reflexive as it might be. Unlike, say, William Yang, another documentary photographer who tells personal stories with a wide social significance, Kanamori does not include herself. Even when she admits that she crossed a line from photographer to friend, she does not pause to reflect about why this might have happened, what it might mean, and how it might impact upon the performance. Indeed, between her modest storytelling and Malcolm Blaylock’s minimalist staging, the show seems to shy away from the possibilities of performance. Umiumare aside, the stage is strangely static and the aesthetic more televisual than theatrical. It is as if by minimising its theatricality, the show seeks to legitimate its veracity but in doing so it displays a paradoxical ambivalence towards performance. Even as the creators seem to trust the medium of theatre to convey the truth, they distrust, and even discard, theatre’s more inventive and imaginative methods.

Whatever its implied attitude to performance, the work is rightly adamant about the injustice done to Chika Honda. Throughout the play, the performers are positioned around the edges of the stage, leaving a black hole at the centre, symbolic perhaps of the hole in Honda’s life, her heart, our hearts and, most of all, our justice system. The show ends with Honda’s enigmatic refrain: “Mum is Mum. I am I. I am Chika Honda.” Even though she has returned to Japan, the injustice done to Chika Honda still haunts us and, the show implies, will continue to do so until our legal system produces another type of documentary performance altogether, the one that clears her name.

Chika: A documentary performance, creator, narrator Mayu Kanamori, director Malcolm Blaylock, musical director, composer Tom Fitzgerald, documentary sound Nick Franklin, shakuhachi Anne Norman, koto Satsuki Odamura, lighting design Keith Tucker, dancer, choreographer Yumi Umiumare, taiko drums Toshinori Sakamoto, sound design Andrei Shabunov, Performance Space at CarriageWorks, Mar 5-8

RealTime issue #84 April-May 2008 pg. 39

© Caroline Wake; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Chris Murphy, Fearless N

photo Heidrun Löhr

Chris Murphy, Fearless N

A POSSIBLY OBSCURE THEME GIVES WAY TO FUN AND FRIVOLOUS THEATRICAL FARE IN THEATRE KANTANKA’S LATEST PRODUCTION, FEARLESS N. BASED ON FEARLESS NADIA, THE ALTER-EGO OF AUSTRALIAN-BORN MARY EVANS, WHOSE UNCONVENTIONALLY STRONG FIGHTING PROWESS AND STURDY PHYSIQUE TRANSFORMED THE ROLE OF WOMEN IN THE BOLLYWOOD FILM INDUSTRY C1950, FEARLESS N TRACKS A REMARKABLY HIDDEN HISTORY—BEGINNING, INTERESTINGLY, ON A DISPLACED BOLLYWOOD FILM SET PLONKED IN THE MIDDLE OF HOMEBUSH BAY.

Enter to tabla drumming and a warm waft of heady incense. Ahead is a shrine-cum-props table, replete with all manner of East Indian paraphernalia. To the right is the pathway for us ‘extras’ to be herded—a role the audience will play to delightful effect throughout the performance. Above the stage sits a film director (Georgina Naidu) who calls the clamouring set to order with humorously intoned requests for singing extras, soldier extras, cowboy extras and dying extras, who should—if asked to die—“please do so without making a fuss.” Naidu’s timbre establishes the self-referential tone that is to underpin our journey: an interpretation of Nadia’s rise to fame through the theatrical contrivance of documenting the story as a Bollywood film. The production hence draws on the tropes of a film genre that is possibly more at home in the theatre itself—using melodrama as the key, farcical connection between the two forms. At the same time, it dips into the politically incorrect giving Fearless N a self-knowing wryness amidst its busy east/west references and marking a “postcolonial field” that even the director admits is “getting pretty crowded.” (Director Carlos Gomes himself appears comically from time to time in a sari as a prostrate beggar with a baby pram).

The production’s most amusing contrivance is its employment of voiceover and live camera work to conjoin disparate stage sequences into the semblance of a ‘real’ cinematic image, projected above the stage action in appropriate sepia tones. Nadia (Chris Murphy) strangles pin-stripe suited villains on top of a moving train (read: Nadia stands above a projection of a moving train and wobbles appropriately); Nadia beats up lazy cowboys who are comically instructed to end their death-fight in the ‘much better’ formation of a human pyramid; Nadia launches into the fight by swinging tarzan-like from a rope, and later, we see her emerge bedecked for a true Bollywood dance-style wedding. At times, the effects are especially revealing, as in a car ride sequence that is generated by a cardboard chassis jiggled in front of a projected moving street scene. Similarly, ‘extras’ dressed as female colonials are given iced tea to sip while their actions are overwritten by suitably plummy voiceovers and a palm-leaf fanning boy behind them.

The text, written by Noelle Janaczewska, offers the potentially awkward theatrical device of an onstage director as narrator, but this actually works well to get a jam-packed story out with ease. At times, there are glimpses of Janaczewska’s signature writing style—a spare prose with tightly spun metaphors that evoke internal character states. This kind of craft is almost out of place in the overall spectacle of Fearless N, but gives it grit and hints at the underbelly of a life that this biography didn’t reveal. The lightness of the production sometimes pushed the narrative into pure parody, and yet the darker textual moments and the question of historical reference hovered temptingly over the work. My desire for real footage of Nadia amidst all of the fakery suggests that Kantanka’s version might just be the first take on a story with more riches to reveal.

Theatre Kantanka, Fearless N, writer Noelle Janaczewska, director, designer Carlos Gomes, performers Rakini Devi, Annette Madden, Chris Murphy, Georgina Naidu, Parth Nanavati, Ahilan Ratnamohan, Rajan Thangavelu, Bruno Xavier, Carlos Gomes, vocalists Ankita Sachdev, Sarangan Sriranganathan, composers Bobby Singh, Ben Walsh, video Andrew Wholley; Sydney Olympic Park, March 7-23

RealTime issue #84 April-May 2008 pg. 40

© Bryoni Trezise; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

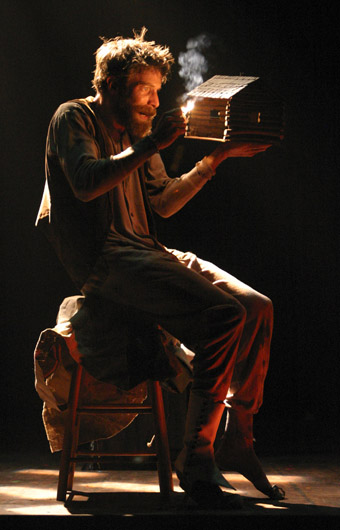

Ross Bolleter, Ruined Piano workshop

photo Shannon O’Neill

Ross Bolleter, Ruined Piano workshop

TAKING THE OPPORTUNITY FOR CHANGE AND RENEWAL, THE ORGANISERS OF THE 2008 NOW NOW FESTIVAL CHOSE TO MOVE THE EVENT FROM “THE POLLUTED, CONFINED SPACES OF SYDNEY’S EXPERIMENTAL MUSIC GHETTOES”, AS THE ANNOUNCEMENT PUT IT, AND “TAKE A DEEP BREATH AND RELOCATE TO WENTWORTH FALLS IN THE BLUE MOUNTAINS.” THIS WASN’T ENTIRELY SURPRISING GIVEN THAT THE AREA IS HOME TO MANY ARTISTS AND MUSICIANS, INCLUDING SEVERAL NOW NOW REGULARS.