aspiration and influence

joelle jacinto: final night idf program

From Betamax to DVD

photo Phalla San

From Betamax to DVD

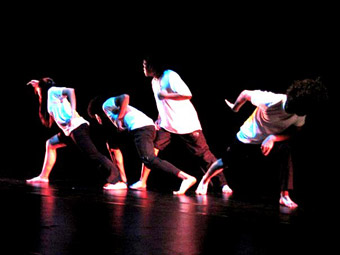

ONE HAND, BENT SEVERELY AT THE WRIST, PRESSES RIGIDLY AGAINST THE CHEST, WHILE THE OTHER IS LOWERED BUT ALSO ANGULARLY BENT AT EVERY JOINT. TORSOS ARE THRUST FORWARD, AND ALL THE WEIGHT OF EACH BODY IS DRIVEN INTO THE LUNGING FRONT LEG, WITH THE OTHER ALSO BENT AND SLIGHTLY OUTSTRETCHED BEHIND. THE HEAD IS TILTED TO THE SIDE, SEEMING TO LOOK AT THE AUDIENCE SIDEWAYS, AS IF WARILY ASSESSING HOW THEY WILL BE ASSESSED IN TURN. FROM THIS STANCE, THE SIX DANCERS IN JECKO SIOMPO’S FROM BETAMAX TO DVD PERFORM FAST, VERY PRECISE, UNCONVENTIONAL MOVEMENTS, STEPPING IN AND OUT OF COMPLICATED PATTERNS WITHIN INDIVIDUAL FLOOR SPACES, EACH TWISTING A KNEE SIDE TO SIDE AS THE FOOT IS LODGED FIRMLY ON THE GROUND. THEY STOP AS ABRUPTLY AS THEY STARTED, THEN BEGIN AGAIN, EACH SEQUENCE DICTATED, OR EVEN ACTIVATED BY, A VOCAL SIGNAL FROM ONE OF THE DANCERS, A YELP OR BARK OR A SHORT, SHRILL CRY.

Every now and then, one or more of the dancers breaks out of their staggered line with an outburst of emotion, a comment to a fellow dancer, another version of the same fast angularity or a completely different, exaggeratedly sinuous movement. But they all return to the original stance, sometimes of their own volition, sometimes to a reprimanding hiss from dancer and choreographer Jecko Siompo. From Betamax to DVD was premiered in 2009 and shot Siompo to stardom not only as a ground-breaking local choreographer, but also as one of “20 Young People in Indonesia Who Have Made History.”

Siompo was the first choreographer featured in the final program of the 10th Indonesian Dance Festival. The bill also included works by Eko Supriyanto and Vincent Sekwati Koko Mantsoe. The trio was a particularly interesting closing line-up: two very different works from major Indonesian choreographers and an invited dancer/choreographer whose work is also vastly different yet exhibits values evident in the preceding pieces. None of these are show-stopping, bravura numbers, which would be the case in a festival in the Philippines, where I’m from, which is why I think this line-up says much about Indonesian culture.

Siompo and Supriyanto’s works, although not similar at all, seem to represent what Indonesian contemporary dance is currently all about. While one is a stream of fast-paced, repetitive movement and the other often has barely any movement at all, they both appear to be manifestations of ideals evident in the previous day’s showcase of emerging choreographers. Indonesian audiences, I have found, appreciate the slow-moving contemporary pieces that make you think, and they are, I’ve been told, rather fond of discussing a work’s meaning after the curtain goes down. The rousing applause that followed all three final night works suggested this might be the case.

Eko Supriyanto’s Home: Ungratifying Life starts with the choreographer crossing the stage with an almost agonizing slowness. Halfway across, he adds a small crouch before the next step, a small lift of an extended leg before the next, a small twist of the body, and so on. All this time, he is enveloped in silence—or rather the annoying clicking of too many audience cameras in a frenzy to capture his every move. But he rest of the piece is “performed” to high-pitched singing and a deafening, incessant whine from the sound score, as different characters approach a wooden frame hanging front and centre—an old, weathered angel, two near-naked men, a man in a pink tutu and a girl walking a dog. They look out from behind the frame as if from a window, peering at the audience as we inescapably stare back. The man in the tutu, revealed to be the source of the relentless singing, pauses only to rudely ask, “What are you looking at?” From a choreographer who has danced for Madonna and appeared in films, Supriyanto is obviously questioning such scrutiny and what all the hoopla is about. What I find compelling is that the audience gets this.

It appears that younger dance practitioners in Indonesia also get what Supriyanto and Siompo are saying and are applying these ideals to their work. The Emerging Choreographers showcase displayed these aspirations. For example, I could see an impulse from the younger choreographers to pepper their works with Javanese poses and gestures, to the same degree that Siompo has drawn from his native Papuan dance forms and reconstructed them to create his own movement. There is also a need to provoke, as Supriyanto does, even if the challenges posted by the younger choreographers are not yet as mature—or as taxing for their audience.

But there are promising ideas, especially from Santi Pratiwi, whose Retorika Kerinduan adequately captures the disquiet of a village whose former inhabitants have all moved to the city for supposedly better opportunities, as well as Joko Sudibyo, whose Cekrek is an engrossing peek into the kind of drama that only goes on inside one’s family home. The movements in Retorika Kerinduan cleverly delineate the differences between village and city—getting away from the city is depicted by running around the ‘village’ at top speed while the ‘city’ captures the villagers with lethargy. Given more time for development, Retorika Kerinduan could be even more striking. In Cekrek, I particularly liked the sharp contrast between the four young boys, who all moved with fluid vitality, and the crying woman whose few moments of dancing were caricatured for comic effect. Perhaps I would have better appreciated the work if I’d understood what she was saying as blithered away to the audience in a local language. Nevertheless, the images had great strength.

In the case of From Betamax to DVD, which I first saw last year, the festival also provided the opportunity to see a work that has been further developed. I detected an increase in the tension between technology and tradition in the updated soundscape of spliced engine noise (cars, planes, machines) and electronics (network buzz, connecting modems) and the stronger responses of the dancers to the score. Perhaps Siompo was pushing this tension more to the surface, or I was more aware of it on second viewing.

Other changes were less successful, with the dancers showing more personality and given more opportunities to dominate Siompo in his role as the outsider. Last year, he was in control—the performers moving in unison and in staggered groups, but always returning to the line at Siompo’s barking command. In this “improved” version it doesn’t seem that the dancers appreciate his presence; one girl even breaks formation to shriekingly chastise him. Perhaps the dancers, some of whom are making choreographic ventures themselves, are becoming more confident, finding their own voices—their yelps and screeches here growing louder and more consistent, symbolic evidence that the Indonesian dance scene is expanding and strengthening.