All that shimmers…

Jena Woodburn

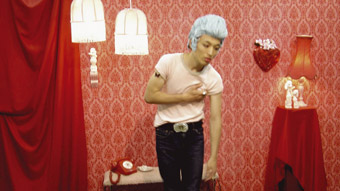

Bianca Barling, Forever, video still

Shimmer’s apt title serves to neatly describe Christian Lock’s holograph and resin wall pieces, Bianca Barling’s richly coloured video and the smooth sleek surfaces of Akira Akira’s sculptures. But the title might also be extended into a more encompassing descriptor, conveying the sense that Shimmer is really about appearances rather than substance.

The works are, for the most part, formally attractive. Christian Lock’s 7 large wall pieces consist of slabs of smooth, richly coloured resin laid over thick swirls of paint smeared on holographic paper. While certainly the most ‘shimmering’ of the works, their interest is more than merely surface, the brush-streaked paintwork providing a 3 dimensional tactility and creating an interior world of infinite detail, despite being impervious inside its resin casing. The works exhibit Lock’s ongoing interest in both the appearance of a material and the material itself, although they replace the previous austerity of colour and frugality of design with gluttonish and lustful over-abundance.

By contrast, the surfaces of Akira Akira’s Snow White I and II are coolly impenetrable. Each curved form lolls on a low plinth like a long white tongue, speaking of the reduction of modernism to a formal template which seems to encompass its aesthetic but not its spirit. Previous work by Akira included subversive touches–objects were shattered and included intriguing details–but these seem docile, blunt, empty, dumb.

In a more literal manner Clint Woodger’s video Sleeper Hold also separates manifestation from its reason for being, combining imagery from the climactic scenes of action films, including explosions, balls of fire, and people leaping, running and being hurled through the air. Deprived of build-up the scenes are also denuded of their power, demonstrating not only Hollywood’s often castigated manipulation of the viewer, but also its reason: without an understanding of the rhythms of time-based work, even ‘inherently’ exciting imagery is dull.

Bianca Barling more successfully builds a completely enclosed world within her film Forever. Visually beautiful and well produced, twin screens are used to depict 2 lovers performing the pain and suffering of love and its end. In their raspberry red rooms, they speak on the phone, look pained and cry, before the girl fires a gun and the boy collapses, clutching his heart. Though its stylised look might be cloying, the romantic watches aghast as the lovers go through their painful motions, heightened by an almost hysterical operatic score in a pantomime both thrilling and heart-breaking.

Sarah CrowEST’s video Globe for Strolling depicts her stumbling about a (soon to be abandoned) local art school campus, sometimes sitting on, sometimes dribbling a large, thigh-high globe, while wearing an identical globe on her head. It’s almost an illustration of the stereotypical indulgences of contemporary art. Rather than being any sort of comment on one’s relationship with self and others, as suggested, its comedy descends into farce as CrowEST struggles to hold her headgear on while blindly staggering along, kicking the globe past a group of students or into a consternated passer-by.

A valiant and powerful essay by Katrina Simmons goes some way towards validation of the works shown. In it, she explains the trials and tribulations of making art and the pitfalls of risk, confusion and failure inherent in the process. Simmons speaks of the artist’s need to discover certain things for themselves, and the inevitability of stumbling a little during the search. Reading it you almost question whether you are wrong for dismissing works as lazy or uninspired. The essay pre-empts other possible criticisms, such as the erosion of a sense of objectivity or meritocracy created by the constant circulation of the same names (CrowEST’s and Barling’s film credits include Akira Akira, while Shimmer’s curator Mimi Kelly also contributed to Barling’s work). Simmons states that Kelly “makes no apologies” for this. A defiant stance? Or a shortcoming celebrated as strategy? Either way, theory doesn’t make up for the oddly self-congratulatory yet dispassionate nature of the works, their reliance on re-visiting old themes and concerns, and the assumption that what is of interest to the artist will necessarily translate into an interesting work of art.

Shimmer, curator Mimi Kelly, Artspace, Adelaide Festival Centre, Jan 14-Feb 27

RealTime issue #66 April-May 2005 pg. 14