adventures in perception

saige walton: en masse and epi-thet, arts house

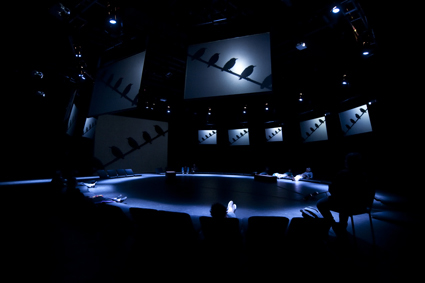

en masse

photo Matt Nettheim

en masse

THE INCREDIBLE SHRINKING MAN (JACK ARNOLD, 1957) CONTAINS ONE OF MY FAVOURITE MOMENTS IN SCIENCE-FICTION CINEMA. AFTER HAVING BEEN EXPOSED TO A MYSTERIOUS RADIOACTIVE CLOUD, THE FILM’S PROTAGONIST, SCOTT CAREY, FINDS HIMSELF PHYSICALLY SHRINKING AT AN ALARMING RATE. DOLL-SIZED, HE FLEES TO THE HOUSEHOLD BASEMENT WHERE HE IS FORCED TO NEGOTIATE A FORMIDABLE ARRAY OF ONCE FAMILIAR DOMESTIC OBJECTS (CRATES, MATCHBOXES, PINS, MOUSETRAPS) AND DO BATTLE WITH THE FAMILY CAT AND OTHER PREDATORS.

Struggling up from the basement to the garden, Carey realises that he might soon become ‘infinitesimal’. He looks up the night sky whereupon tiny and immense phenomena suddenly become intertwined. As his body dwindles to the sub-atomic level, the camera shifts skywards to reveal grand-scale celestial bodies and astronomical vistas. The garden and Carey dissolve into a succession of stars while Carey’s voice-over reminds us that even the “smallest of the small” matters in the larger scheme of things. For myself, what makes this sequence such a powerful and incredibly poetic moment is its refusal to set-up the ‘large’ and the ‘small’ as oppositional perceptual terms. Indeed, Carey himself comes to understand perceptual scale as relative: “the unbelievably small and the unbelievably vast eventually meet”.

The mobile and sliding scale of perception is by no means specific to the realm of science-fiction?just think of how tiny things such as a childhood treasure box or dollhouse can contain endless imaginative possibilities while immense landscapes or intricately detailed aesthetic objects hold the capacity to make us feel small, inferior or insignificant, by comparison. Our perception of the large within the small or the vast within the miniature alerts us to the dynamism that is seeing itself; the ways in which embodied encounters can unleash a sense of eeriness or displacement as well as liberation in aesthetic experiences, through the power of what the experimental filmmaker Stan Brakhage once beautifully described as the sheer ‘adventure of perception’.

Perceptual scale—through the experience of visual and sonic shifts between the grand and the miniscule, the intimate and the elusive—was fundamental to the two mixed media installations, en masse and epi-thet, that were presented at Arts House for this year’s Melbourne International Arts festival. Neither work, however, could justly be described as awakening the kind of sensual engagement or intellectually curiosity that might be befitting of Brakhage’s perceptual ‘adventure’. While filled with intriguing conceptual promise, the conjunctions of imagery, sound and setting that occurred in each installation either failed to deliver upon their intended poetics, make maximum use of our visual and sonic immersion within their respective spaces or induce a perceptual de-familiarising of the everyday.

en masse

En masse is the result of an artistic collaboration between Australian recorder virtuosi, Genevieve Lacey, and UK filmmaker Mark Silver. Silver provided the footage for its multi-channel projections which display migrating starling birds, shot against a stark grey sky at sunrise and sunset. Silver’s footage is luminous and evocative, with the birds initially appearing as distant and almost abstract patterns, only to resolve into closer figurative detail (beaks, feathers) as the work unfolds. From a series of initial musical improvisations to which other musical collaborators (led by Lawrence English) were invited to respond, Lacey has designed a purpose-built soundtrack to accompany the footage. That electroacoustic track is synced to the imagery of the flocking starlings, at the same time as Lacey performs live within the half-hour staging of en masse.

While touted as ‘part concert, part installation, part film’, en masse does not make for a cohesive fit. That disharmony has nothing to do with Lacey’s obvious skills as a performer/composer nor with Silver’s often stunning footage. Rather, it arises because the different elements of en masse (performance, sound, time-based installation) are in phenomenological conflict with one another. During the performance Lacey’s spotlighted presence, gently wandering about the space, actually distracts from fully attending to the projected imagery or attuning oneself to the soundscape. Similarly, the clunky black-box installation feels at odds with the artistic intent of creating a heightened perceptual state for its audience. Ushered into a circular room, we must lie down to experience en masse; yet, its projections are of variable sizes and the audience is only able to see what is directly in front of them. The effect is disempowering rather than sensually immersive, effectively restricting and minimising our field of vision to 180 degrees. In this performative mode, the work seems to be unsure whether it is intended as theatre or installation and its uneasy mix of media ruptures our affective and mnemonic engagement with the sights and sounds on show. However, en masse was also viewable as an installation without performance during the day. On these occasions, the audience was largely left to their own devices and could potentially view the work from a range of positions and as a purely audiovisual experience.

epi-thet

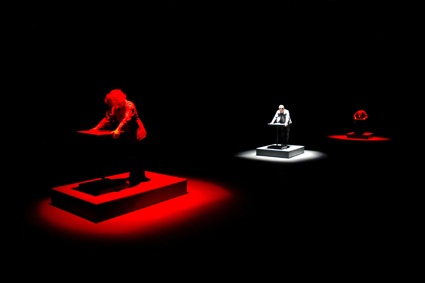

photo Dean Petersen

epi-thet

epi-thet

Epi-thet (Madeleine Flynn, Tim Humphrey and Jesse Stevens), by contrast, makes highly considered use of the Meat Market in its sound-based installation. Upon entering the work, sounds emanate from all sides, ping-ponging and ricocheting through the vast space. The visitor encounters three platforms lined up horizontally, each suffused with a soft red light as the piece rests in its ‘inactive’ mode. Attached to each platform are a series of mounted microscopes. As you step onto the platform, the light abruptly changes to a white spotlight—chromatically alluding to the fact that both you and the work are here to engage in a mutual performance. The sound and light shows that accompany each viewing of the microscopes are unique; generated by the height and posture of the participant, as well as the particular time of day.

Yet for all its insistence on individual composition and the presence of the participant as being crucial to the work, epi-thet remains eerily disembodied and inaccessible. The sounds that are generated are often indistinguishable, lacking in expressivity or material sources in the world. The linkages between the ‘sonification’ of medical research data, the interactivity of the piece and the microscope animations (tiny bird-like objects accumulating in patterns, with text fragments) are also unclear. Instead of amplifying our engagement with the work through the lures of sound—by playing to the fact that, as French theorist Michel Chion suggests, sound itself is decidedly un-framed and able to ‘fill’ a space in ways that an image cannot—epi-thet ends up subjugating our sonic involvement to the tiniest of visions. As we struggle to discern and understand the miniscule animations contained in its microscopes, sound drops out of the experience at the expense of vision.

Given their perceptual mismatches between the large and the small, as well as vision, space and sound, it is disheartening to find that the conceptual promise of these works has not been realised.

en masse, composition and performance Genevieve Lacey, film Marc Silver, installation sound Lawrence English, musical collaborators Steve Adam, Taylor Deupree, Christian Fennesz, Ben Frost, Nico Muhly, dj olive, lighting designer Paul Lim, Trafficlight, systems designer Pete Brundle, nice device, costume designer Paula Levis; Arts House, Oct 19-23; epi-thet, creators Madeleine Flynn, Tim Humphery and Jesse Stevens; Arts House, Oct 19-23; Melbourne International Arts Festival, Oct 6-22

RealTime issue #99 Oct-Nov 2010 pg. web