a return to vulnerability

jacqueline millner: artspace: kosloff, frankovich, haseman

Laresa Kosloff, Sensible World, Artspace, Sydney, 2009

WHILE NOT PART OF A THEMATICALLY LINKED EXHIBITION, THESE THREE DISTINCT INSTALLATIONS ALL EVOKE A SENSE OF NOSTALGIA FOR A TIME OF SIMPLER TECHNOLOGY, PURER ARTISTIC PROJECTS AND MORE HUMAN-SCALE MODES OF REPRESENTATION. TOGETHER, THE MATERIALS AND FORMAL LANGUAGE THE ARTISTS USE, FROM EARLY MODERNIST ABSTRACTION TO SILENT CINEMA TO OBSOLETE VISUAL APPARATUS SUCH AS SLIDE PROJECTORS AND SUPER 8 FILM, SUGGEST A RESISTANCE TO THE GLOSS AND GLITZ OF 21ST CENTURY MODERNITY AND ITS THOROUGHLY MEDIATED SPACES; RATHER, THEY BETRAY A DESIRE TO TEND ONCE AGAIN TO THE VULNERABILITY AND LIMITATIONS OF THE HUMAN BODY AND HUMAN AGENCY. THAT FOCUS ON THE BODY IS UNDERLINED BY THE STRONG INVOCATION OF PERFORMANCE THAT THESE WORKS ALSO SHARE.

Laresa Kosloff’s Sensible World comprises four silent videos projected on small flat screens suspended from the ceiling. Kosloff has been documenting snippets of social interaction in public spaces for some years. Here she has juxtaposed glimpses of Central Park roller-bladers, jog-a-thon competitors, urban trapeze artists and a laughing club meeting around a fountain. Each video has been shot on Super 8, the technology that made the first home-movie possible, then transposed to DVD, three in black and white; each retains the graininess of the original medium, together with its nostalgic glow and analogue warmth. The uniform format, absence of soundtrack and faded documentary/home-movie aesthetics effectively de-contextualise the images from their specific time and place, rendering them equivalent. We are encouraged as viewers to look for the similarities in the scenarios: the way choreographed movement intersects with the cultivation of group identity and belonging, the way shared performance can positively claim pubic space, the way the idiosyncrasies of self-expression rely on drilling a common physical language. The images activate a tension between conformity and individuality, social control and its evasion, and the role of the performing body in negotiating this fine line. Yet the work ultimately affirms the ability of the individual and the casual group (as much as the artist) that each ‘performs’ in unexpected ways to resist the colonisation of public space by vested commercial and political interests. Moreover, the apparent ‘timelessness’ of the footage checks our instinct to treat this ability as quirky nostalgia.

Kosloff has in the past collaborated with Alicia Frankovich, and it is easy to see why, given their work shares certain sensibilities and concerns, both engaging with low-tech media and the poetics of the human body. Performance is integral to Frankovich’s practice, whether explicitly enacted or implicitly referenced. In part this comes from her background as a competitive gymnast. As a strict regime that openly aims to discipline the body and construct it in as technically perfect a form as possible, gymnastics is a powerful metaphor for the subtler injunctions to perform and conform that our bodies suffer everyday in contemporary culture. Frankovich’s performances, recorded on video and projected small-scale at floor level onto obsolete technological hardware, are reminiscent of seminal video-as-mirror works such as those by Bruce Nauman and Vito Acconci, where the artists recorded the banal minutiae of their studio routine, or observed their endurance of absurd physical rituals.

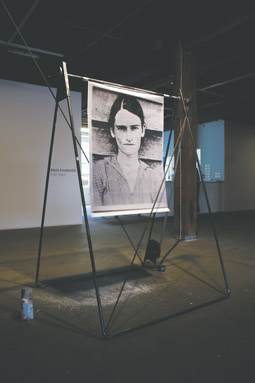

installation view, Alicia Frankovich

photo Silversalt

installation view, Alicia Frankovich

In the most compelling component of this installation, Frankovich has constructed a simple metal armature that brings to mind the uneven bars, complete with gymnast’s chalk. Here she has suspended a poster-sized photocopy of Walker Evans’ portrait Alabama Tenant Farmer Wife [Allie Mae Burroughs] (1936), an icon of both the Great Depression and activist documentary photography, made doubly famous by Sherrie Levine’s appropriation of it in After Walker Evans (1981). In Frankovich’s version, the image vibrates as the metal apparatus squeaks in a semblance of old-fashioned hand-cranked copying; the image is condemned to be endlessly copied to retain its acuity, just as a gymnast is condemned to endlessly drill her routine. Yet, as in Kosloff’s work, the low-tech aesthetics serve to remind us of the possibility of (manually, literally) intervening in the transmission of mainstream meanings.

Shane Haseman’s installation also makes reference to the potential of art to offer a counter-discourse; he borrows both the language of utopian modernist abstraction (especially Malevich and Rodchenko), and the title of The Rolling Stones’ 1968 hit “Sympathy for the Devil” that enveloped the band in allegations of devil worship given the song’s portrayal of Satan as “a man of wealth and taste” who playfully toys with mortals’ puzzlement at “the nature of [his] game.” Haseman’s work might be described as a tasteful puzzle. Despite being painted on cardboard, that quintessentially throwaway material, there’s nothing cack-handed about Haseman’s radically reduced abstracts. They are meticulously rendered and arranged along the gallery walls with geometric precision, propped up by poles that recall home-made protest signs. The gridlock in which the images are held belies their potential to liberate imaginings of alternative societies with their ground zero aesthetics. To crack the puzzle may require upturning this order, animating these symbols with the messiness of bodies that might ‘perform’ them in public. Yet the visual language remains exhausted and largely mute, such that the work adds little to the re-deployment of modernist abstraction by artists such as John Nixon and his acolytes.

A sense of small-scale, very human resistance to the lightning-speed, high-tech vision of contemporary culture permeates these works. They insist on the presence of the human body and the importance of the hand-rendered; they accentuate the continuing potential for transformation in the minutiae of everyday life. In particular, watching Kosloff’s grainy glimpses of social interaction in public spaces, we are moved by the integrity of human beings—incarnated both in the anonymous figures who roller-skate or laugh in public, and in the artist herself—who in their modest gestures pursue their Sisyphusian quest to render the world meaningful.

Laresa Kosloff, Alicia Frankovich, Shane Haseman, Artspace, Sydney, April 24-May 23

RealTime issue #91 June-July 2009 pg. 50