November 2023

Jenny Fraser is a tough-minded, playful provocateur, a bricoleur who will use whatever media and images are at hand to celebrate First Nations culture and to right the enduring wrongs done by racist colonisation to her fellow First Nations Australians.

Jenny is a self-described “digital native” — a play on her heritage and her intimate engagement with digital technology as it emerged in the 1990s and evolved across the course of her career.

Alongside r e a, Brook Andrew, Tracey Moffatt, Karen Casey and others, Jenny is a member of a trail blazing generation of First Nations Australian artists who boldly engaged with video, film and the new media tools and communication networks of the 1990s. For Jenny, the digital is one means among others, but a key one: “The Internet has been such an important platform — otherwise we would still be in the dark.”

A trained artist and art teacher, she mastered computer art tools, CD-ROM and online interactivity, and employed the internet communally through her pioneering cyberTribe Online Indigenous Gallery (see Djon Mundine’s “Jenny Fraser: The cyberTribe odyssey”) to extend the reach of her own work and that of other First Nations artists here and overseas.

Jenny’s Aboriginal country is the border district between Queensland and New South Wales, the land of the Yugambeh-Bundjalung people. Her language dialect is Migunburri Yugambeh. Land and language are central to her life and art.

Jenny has received numerous awards, including an Australia Council Fellowship in 2012 and the prestigious Australia Council Experimental & Emerging Arts Award in 2022. When asked how she felt about being awarded the latter, she wrote: “The award helped me to survive during the pandemic, while we were being locked down in the Penal Colony. The timing of being notified that I won this was divine, as it was the same week that the University of Queensland reneged on a teaching job that I was doing. It was a precarious time to be an artist. Later that month the 2022 floods came as well, it was apocalyptic, but I was able to manage to keep on keeping on. More power to my ancestors, as I am usually being looked after in this way” (email, 15 Oct, 2023).

Jenny’s work has appeared around Australia, including a history of over two decades or more exhibiting with the Boomalli Abiriginal Artists cooperative in Sydney and more often overseas in galleries, film festivals, public spaces and online exhibitions. She has forged connections between First Nations peoples in Australia, the Pacific and the Americas.

Jenny’s PhD thesis — The Art of Aboriginal healing and Decolonisation (2017) — comprehensively delineates the trajectory of her career and activism, but above all reveals her anger and despair over the limited support offered her and the community of artists she supports. It reflects a turn not altogether away from art (she completed an impressive film, Trouble in Camp, in 2020) but very much towards a long-evolving focus on Indigenous healing and well-being, including her own. See her article Look Good, Feel Good, The art of healing, Artlink, vol 30.

The following discussion with Jenny Fraser about her art comes from a long telephone discussion we had in October 2020 which was subsequently edited with some contextual material added over 2022-23.

Although Jenny’s art is inseparable from her activism, curation and care about Indigenous well-being, I asked her about the why and how of her art practice in order to gain a greater understanding of her motivation, aesthetic and political. We discussed individual works and series and later moved on to address Jenny’s evolution as an artist.

PHOTOGRAPHY AND SPIRIT

Photography recurs across your output, as in the Hit the Road and Roadkill series. A hauntingly beautiful image of a dead owl in a tryptych in that series appeared in the Feathers Float exhibition you curated at Other Gallery while in residence at the Banff Art Centre, Alberta, Canada in July 2005. It also won the Photography Category in the Gold Coast Indigenous Art & Design Award in 2006.

The series was based on roadkill of native animals on lands in the Bundjalung Nation. It’s also representative of how native people are treated by wider society in Australia — widely ignored and denied after impact, just like roadkill.

The image of a magpie in the same triptych looks rather like spirit photography with the bird’s feathers appearing to dissolve into mist.

I think you’re right, there’s a spiritual realm in photography. With the owl I also left the top of the head off out of respect because it was a bit messy. I found the design on the feathers really fascinating. I have been doing photography for a long time, ever since my Dad gave me my first camera when I was about 10 or 12. I had a practice of making art and photography before I was a professional artist.

Are there many images in this series?

I haven’t counted them, but there’s a lot. I take them all the time. Most times when I see roadkill, I stop — unless I have a lot of a particular species already.

You like creating series?

I like the spontaneity of it where the spiritual realm provides the art department for you; you don’t have to set it up.

What is the significance of Tallebudgera Shell (2014), a photographic print on canvas?

At the time I was creating another work titled Midden (a collaboration with Native American artist James Luna, Adelaide Festival, 2014). The shell I refer to comes directly from a midden that our old people would have shared at Tallebudgera, which is part of the Burleigh Headland, a national park on Kombumerri Country that’s close to the New South Wales/Queensland border. While I was researching middens I found there wasn’t much out there on the internet about them that I could identify with. I was also trying to get a hold of our ancient shells because you don’t see them anymore. People have picked over them. I wanted to put Yugambeh-based shells into our consciousness of middens.

ANIMATING PHOTOS

You also animate photographs on video, as in I Am What I YAM (2’24”, 2009), with its thumping, ritual-like soundtrack. You like wordplay and making pop culture references; here you use Popeye’s grumpy self-assertion, but what does it have to do with the yams that appear onscreen?

I took a series of photographs in Noumea in New Caledonia and animated it. I couldn’t take the yam home with me, so I staged the photos there. It was made as a joke really. At the time there was a lot of harassment of people with different ideas about gender and sexuality from our government and the church. I wanted to make light of the situation to say how this kind of thing is normal in nature; a lot of plants and animals have different genders and sexuality and they can live with it, so why can’t we? There’s a woman-shaped yam and a man-shaped yam and it’s funny because the man shape is so hairy. The video has appeared in a number of animation festivals.

You’ve also created computer graphic works such as The creative cell of life (2008 Darwin Entertainment Centre Gallery).

There are two works in that piece. One is a series of paintings, a triptych; the other was created on a computer. It’s like a mandala. Maybe it’s the view from the perspective of a cell.

It looks like a layered series of arches with dark, rainbow-like patterning. It’s quite striking. How did you create it?

It’s a sunset I’ve manipulated to create that rainbow effect. It’s related to cells because it has that rounded kind of structure.

True to the title it has an almost a cellular look.

Yes, and repeated. I referred to the work with a quote from Aboriginal scientist David Unaipon (1872-1967): “She gave birth unto the first female of life of flesh and blood, the mould and pattern for all the mothers of the Earth. She endowed her Infant Female Child with faculties and powers to conceive just what the human race is today.”

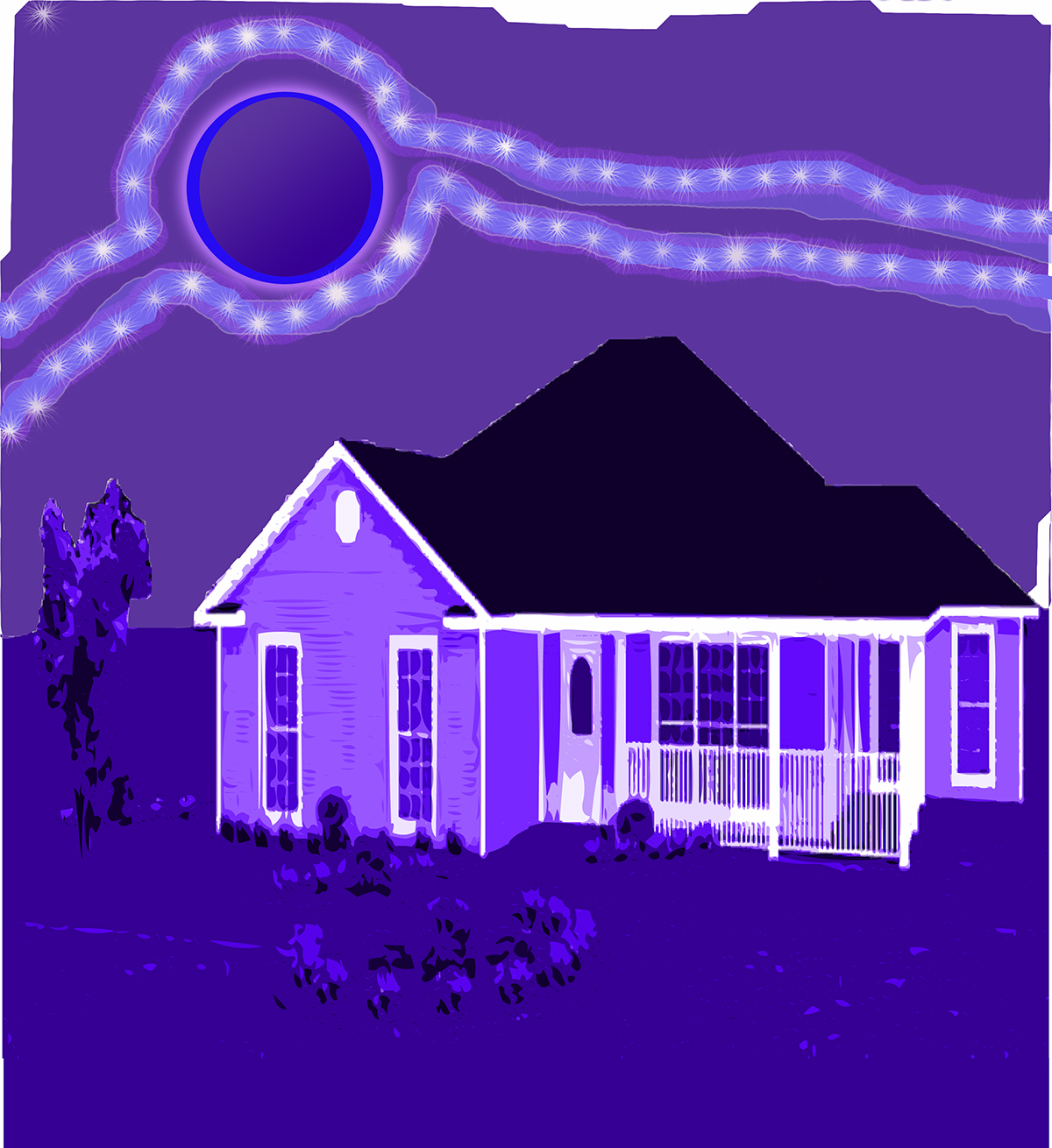

Nokturne (2006) is a graphic artwork in which a 1950s Australian suburban house is embedded in Aboriginal cosmology — the sun, earth and sky each with their own distinctive patterning.

That was another series because at the time I was interested in Aboriginal architecture. I took examples of mainstream Western architecture and placed them in the Aboriginal landscape. I was trying to make a statement: it doesn’t matter what something looks like from the outside, the essence of Aboriginality is always there.

Night-time crops up repeatedly in your output, as in in Hot August Nights (2006) and in Cut it out (2006), an installation for NAIDOC week in the window of the Queensland Performing Art Centre (QPAC). You evoke a purplish twilight heading into night. It’s quite seductive. The installation included a cut-out “Brown Babe” doll.

I grew up in far north Queensland and that’s the normal time when you visit people and get creative because it’s a bit cooler. It’s too hot in the daytime to do anything. The housing estate that Brown Babe floats above could be where she lives — or where any of us live. The houses themselves are also cut-outs, replicating suburbia in a time gone by or a time in the future. Brown Babe has risen above suburbia. She enacts culture to forget and to remember. It uplifts her spirit.

MONTAGE: RECYCLING BY HAND

In 2002 in RealTime, Christine Nicholls wrote about your Faster Foods series:

“Fraser’s works are intelligent and witty, with a wicked sense of humour that belies the seriousness of her approach. For example, her deeply iconic Faster Foods critiques the fast food industry and consumerism, references Australia’s choice of national symbolism and the QANTAS logo, and raises questions about the appropriateness of hoofed animals in Australia and this country’s entrenched eating habits. Because her image taps into so many existing representations of the kangaroo, both literal and metaphorical, it’s possible to read it on many levels, despite its surface simplicity. With Faster Foods Fraser has succeeded—very cleverly—in appropriating the appropriators.”

You work a lot with photographic and video montage. I’m curious about Raw Roo (2005) with its ironically alarming “Kill Faster” sign. How did you put this work together?

That’s from my Faster Food series begun in 2002. I’d seen a T-shirt that had a dog chasing a cat. I wanted to ‘Indigenise’ that and make our own. So, I came up with “Faster Food.” I’ve had a long-term interest in bush food because my Dad was a hunter. When I was a kid, I used to go with him all the time and harvest or catch bush food or birds and also identify a lot of plants. I wanted to bring him into it a bit. He killed a lot of kangaroos as well. So, for that piece I used a pin with a little golden kangaroo on it, like the souvenir that you take with you overseas. I took a photo of it and heightened its colour in Photoshop, to create the look of a neon sign.

In your artist statement you called Faster Food an anti-ad, describing it as “positive propaganda.”

To encourage the Indigenous community to be mindful of their genetic makeup and eat more healthy foods. To ask why don’t we have the option of eating fast foods that are native to this land. Think about the kangaroo. In urban society we usually only see it as a gourmet delicacy or pet food… it’s modern day kitsch food! The message of Faster Food comes out of the black — telling us we need to go ‘black to basics.’

Have collage and photo-montage been important in your work — that cutting and pasting, rearranging and juxtaposing?

Yes. I showed Faster Food on a light box, perfect to get a neon glow. Other montage works I present on paper. An exhibition featuring one of my collages has toured overseas because the curator of Contemporary Australian Drawing, Dr Irene Barberis, took all the works with her in a suitcase. I did draw but it was mostly a photo-montage, titled “vultures of Cultures.” It’s good to have transportable work like that.

I’ve been using a collage practice for a few decades now. I like it because it’s recycling and I don’t usually do it on a computer, I do it by hand. I can’t bear to throw out striking images. A lot of the time, when you look at magazines, there’re hardly any good images so I try to pick the good ones and rearrange them how I want — that’s my power in the process.

I’m curious about the Mumsy’nt (1999) collage which features Queen Elizabeth pictured in front of the Sun.

I’m glad you read it that way; other people haven’t recognised the Queen. They think I’ve used a picture of my Mum or Grandma. I wanted a picture of the Queen and at that time I couldn’t find that many on the internet. Historically you weren’t allowed to use or deface photos of the Queen — it was actually illegal. The only picture I could find was from a monarchy website in Canada where she looks very young.

It’s a funny, ambiguous title.

I was trying to use humour to make a statement. At that time some ATSIC (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission) representatives went to talk to the Queen about some issues because they weren’t having any luck with the Australian government. She refused to speak to them. It would have helped if we had a treaty. Indigenous peoples in other countries, such as New Zealand, can call on their treaty and the Queen has to respond. I don’t actually agree with the idea of a treaty myself. I think that you can break a treaty as well as keep it. But I was horrified that the Queen could be so disrespectful as to ignore Aboriginal Elders. So I wanted to ‘indigenise’ her and to envision what it would be like if we had a monarchy that was supportive of Indigenous peoples all over the world. The Sun references the Aboriginal flag except it’s upside down, which makes it the international distress signal.

Is this a work that you printed and distributed?

I showed it for the first time at the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Award in Darwin around 2000. I also submitted it for the NAIDOC art poster in 1999. I think some people were scared to disrespect the Queen so they didn’t use it, but I got some good feedback. In news stories about the NATSIA awards people would stand in front of it. I think subconsciously they wanted to use it. I also gave the copyright for its use to RMIT (Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology) when they had a conference in 2001 titled Treaty, Trick or Truce. They used it on everything — posters, T-shirts, badges, bags. So it got disseminated a lot.

You’ve developed a variety of practical strategies for getting your work shown.

Some ways of working are so expensive: prints, framing, mailing, freight. So, along the way, I turned to what I could mail easily like DVDs, little prints and stickers and whatever. Then I got to the stage of doing photo books. The Chinese artist Ai Wei Wei talks about how we can use photo books as transportable exhibitions, which is true. Sometimes I would mail out a book with everything which can sit in a gallery as well. It looks really professional whereas a piece of paper doesn’t. I make a few, but I don’t farm them out as books, more as artefacts.

ANIMATINGS

Let’s talk some more about animation. Tell me about Nature in the Dark II (2015), which appears in Unlikely, La Trobe University’s online Journal of Creative Arts. The unusually vivid purple and red-fringed sea creature is accompanied by a powerful soundtrack.

I was asked to collaborate on an art-science project titled Nature in The Dark for my role as an Associate Member of the Centre for Creative Arts at La Trobe University. I was given a hard drive featuring images from various locations and from it I chose Bunurong because I wanted one with an Aboriginal name and I think that was the only one. Bunurong National Marine Park is off Victoria and is also the name of the traditional owner group within the Kulin Nation. I wanted to make the jellyfish dance. It’s just a simple thing, just over one-minute. I was fascinated by the other-worldliness of the underwater life there. My intention was to manifest an Aboriginal aesthetic in the work, to communicate old and new cultures across languages and other borders.

For the soundtrack, I used a work by Mark Atkins. The main instrument in the composition is a bull roarer — just a piece of wood on a length of string, swung around to make that noise. It has an otherworldly feel. A Native American filmmaker really loved this, because they have a similar instrument in the USA.

You were invited to contribute to the Forever Now project by the Melbourne artist-led experimental art organisation Aphids, in which works by 44 artists were put on a gold record to be sent into space — a follow-up to the Voyager Golden Records sent in 1977 by NASA. Your contribution, australienation (2015), is a short, striking animation in which a sudden ray of light appears over a dark ocean. How did you capture that image with its a sense of awe and ephemerality?

The video was taken on the Great Barrier Reef. Some people think I’ve manipulated the picture, but the ray was just the result of lens flare on the day. The light is spectacular out on the reef. It’s also to do with movement and capturing the sun. It’s a simple work that I like re-using, so I used it again for australienation. I wanted to communicate something historical: we have this beautiful Great Barrier Reef and in a couple of decades it will be dead, so the time to act is now and we can reflect on it later. So, I sped up and then slowed down the video and I kept doing that so the image has a very unreal kind of feel, because it’s losing and then gaining frames.

FILM: A FIRST NATIONS PERSPECTIVE

You’ve moved on from making short videos, like the politically satirical Name that beach movie II (2014) to Trouble in the Camp (2020), an ambitious 30-minute film which premiered at the end of 2020 in London’s Native Spirit Film Festival, an annual event that celebrates the world’s Indigenous cultures.

The whole point of making the film was because not many people in Queensland make films. It’s so culturally oppressive here: hardly any Indigenous films are funded and even fewer get made. If you’re an artist wanting to make a film, you’re told by the arts funders to go to the film fund, then vice versa, which is really complicated and so unnecessarily stressful.

In the film, we see a girl in country. She’s integral to it, living alongside animals, birds and insects. Then she appears as a worker in a mid-19th century frontier kitchen, and then in a protest challenging the Commonwealth Games in Brisbane in 2018.

Jinda, the young woman, played by Ruby Wharton, is reincarnated over different lifetimes. Each character is actually based on the life stories of my old people including a CleverWoman, a midwife, an artist and an activist. The film has a unique structure that I’ve been working with and developing in other art forms, including the other[wize] series, and my upcoming novel, for around two decades.

The film brings together your strengths in editing and montage and the use of sound. How was it pulling it all together?

It was only a good feeling when it was finished! I filmed it over a decade and it’s taken six months or even a year to edit. I suffered a lot of anxiety over it and procrastination made it worse. All the sort of stuff that artists go through. I know now why ‘wellbeing’ for filmmakers is spoken about, because it’s a very lonely process.

In the first section, the beauty of the lovingly framed images and the rhythmic editing between Jinda and the bush creatures is perfectly supported by the music. Where did the music come from?

I wanted to make a showcase of a number of Aboriginal musicians. I thought, if my film travels I can take a few of them along with me. I was lucky because although I didn’t have any money most of them, such as Fred Leone, OKA, Eric Avery, let me have their songs and were happy to share the love. I was also lucky I had filmed the 2018 Commonwealth Games protests about the disadvantaging of Australian Indigenous and Torres Strait Islander peoples, and although I didn’t know Ruby Wharton very well‚ I knew her father. She turned out to be one of those young people who are into everything — organising, protesting, performing spoken word.

INSTALLING A COUNTER-VIEW

You’ve also made a number of installations. In Outblack (2006) for Melbourne’s Next Wave Festival, the Blackout Collective, in a collaboration between yourself and Cameron Goold, placed native grasses in and around a shipping container, effectively declaring country to be uncontainable by the tools of globalisation. At the same time, your title reclaims country from the notion of “outback” by converting it into “outblack.” Have you done much in the way of installation?

In Outblack we presented ancient native Australian plants such as Cycads and Grass Trees (‘Black Boys’) and the idea of the ‘uncontained’ and the issues around native versus introduced, inclusion versus exclusion, and ancient versus recent.

I gave installations a rest for a while because it’s so complicated when you have to work with other people — like installers in galleries who have different ideas or levels of commitment. That was good for The Containers Village, but it was also really limited — I wasn’t allowed to paint on the outside of the container. Some people were but you had to get permission beforehand, so I only got a few lines in before I got in trouble. I actually wanted more plants but because I was working in Victoria it’s more difficult to access plants and really expensive. I’m not used to that because in Queensland we can just walk into our yard to get plants, they’re everywhere.

I do enjoy working on that scale. I showed a similar work in 2009 for the Strand Ephemera art walk on Townsville’s Esplanade, with australienation showing in a container. I think there’s a lot of resonance with a shipping container, because it speaks across cultures, it speaks a lot to the Asia-Pacific region and also Africa.

CD-ROM: RE-ENACTING & RE-CONNECTING

You embraced CD-ROM while it remained a viable platform, including one accompanying your PhD, titled Get Creative! The Art of Healing and Decolonisation (2017).

I did a couple a decade or so before my PhD. One is called Yanbali Gawulah (2000) which is a Yugambeh saying that translates as “walk around far” — sort of like, “walk on country seeing different things.” I would have done more CD-ROM works at the time but it wasn’t easy — all that coding. A group in England called Mongrel gave out their software so I did a CD-ROM called other[wize]. It was shown in Brisbane and at ISEA2006 Inter-Symposium of Electronic Art in San Jose, California. The structure of Yanbali Gawulah is actually the basis for the film Trouble in the camp, in terms of the scenes.

In what way?

Nine frames in the CD-ROM lead to nine stories, each with a Yugambeh word, so it’s similar to the film which I’ve broken up into six chapters. In the film each one starts with a word which sums up the whole scene, if you know the language. The CD-ROM was based on my family history, celebrating the people and place of Yugambeh in South East Queensland and my family’s movements beyond, using old family photographs, Yugambeh language, sound, along with contemporary documentation of country and remembering.

With the film I’ve done the same, re-enacting family stories. The viewer might not necessarily understand that, but I’ve used my knowledge of my family and country to tell that story.

You’ve also explored the possibilities of online interactivity with a work titled unsettled, adapting some of the CD-ROM material (see a video walkthrough of unsettled above). It received an Honourable Mention at the imagineNATIVE Film & Media Arts Festival in Toronto in 2007. You wrote about it on Vimeo :

“A vital aspect to the development of ‘unsettled’ was a process of revisiting and an exploration of country, learning and using Yugambeh language and other opportunities for re-connection to make sense of lived experience and also understand the extent of trans-generational trauma derived from massacres and the many other injustices of the day. Through engaging in this process, and gaining strength from my family’s own inner knowledge and solutions, the project stands as a legacy that allows my family stories to be offered up as an alternative to the mainstream Queensland version of the history of colonisation.”

BECOMING AN ARTIST: ART WAS MY FRIEND

How did you start out as a young artist?

I went to a lot of schools, about 13 in all. Basically, art was my friend, my outlet for a stressful home-life and a way to relax and to deal with the heat. I was naturally good at it, based on what other people were saying, but I just did it because it was peaceful.

At what age did you start drawing and painting?

I’ve been doing it all my life, but I won my first award when I was 12. Just a good little art show award in a place called Giru near Townsville. That was actually about the Great Barrier Reef as well. It was an underwater scene that had a scuba diver with coral, done with craypas. Then I started taking photographs when my Dad gave me a camera. It was lucky because when I was in high school, in our senior years, we had an elective for photography and then later videography. We had a Canadian teacher who would offer that instead of sport — you know, lawn bowls on a Wednesday afternoon. We used to make our own ads for Jag or whatever and do trick cinematography.

That was a good start. Then when I went to the University of Queensland I began to miss doing visual art, so then I changed courses to Art Teaching at QUT instead. My other major aside from Art was Film and TV; I really loved that. It wasn’t just practical it was also theoretical. We did gender and media studies. That’s where I learned to be critical. I started writing critically about unpacking issues in Australia. After that, I became an art teacher and taught photography and film theory as well. When I was studying I didn’t really care about visual art that much because I found it easy to put more effort into and find more excitement in film and TV. So my practice has always been somewhere in the middle.

When did you start making work for exhibition?

I was exhibiting in Cairns in the 1980s, but no-one ever talks about that, not even in Cairns. (LAUGHS) Back then, there used to be exhibitions in shopping centres, so it was like grabbing people as they walked past. The mainstream is just such a non-art society. The Cairns Indigenous Art Fair is up there but it’s run by outsiders and actually ignores the locals and focuses on Torres Strait, Cape York and Stradbroke Island art and flies artists up from Brisbane all the time. It’s still like that even though some people have managed to rise above it and engage with the art world elsewhere in the world.

In the 1990s, I went to the University of Queensland and exhibited with their Fine Art Society. Then I changed to QUT and showed mainly in student exhibitions. Even in the 90s not much art stuff was happening in all of Queensland. That’s why the Internet has been such an important platform, as I said, otherwise we would still be in the dark.

How did you manage to find a niche for your work, or has it always been a bit of a struggle?

Queensland can be pretty horrible; that’s the basis of my PhD. I wanted to write about how art is healing but what I ended up writing about was how you can’t heal if you live in a culturally apartheid society. And it’s still like that. The beauty of escaping Queensland is that you can go and do interesting things elsewhere. The pandemic restrictions disabled that, but it’s how I got my film edited. So, it’s been a blessing and a curse.

Speaking of ‘escape,’ you’ve established connections with North American First Nations artists and institutions and you’ve managed to exhibit works in the US, Canada, Japan, the UK and elsewhere. You’re not well-known south of the border here but you have a presence overseas.

I encourage other artists to do that as well. If they say, “The gallery wants me to be in a show, but they want to charge me this amount of money,” I say, “You could take that money and go overseas, make your own exhibition and have a better time doing it.”

………

There are many dimensions to Jenny Fraser’s art, ranging from “the spiritual realm [that] provides the art department” in her images still and filmed of animals and country (and the Great Barrier Reef), to deep immersion in, and love of, family and history in her CD-ROM creations. It includes outright anger alongside often drolly expressed protest in pungent visual and word play. Jenny’s means are many and highly adaptive, guaranteeing they are far reaching. Collectively her creations, from the most substantial to the bluntly agitprop, operate as a constantly unfurling collage of images jokey, caustic, seductive and simply beautiful, even when, as in my case, the paintings and installations can often only be glimpsed on screens.

CODA: CODE FOR THE FUTURE

In 2020, at the end of an account of her family history written for SBS TV’s Insight, Jenny wrote “…as an artist, I am leaving a code for future healing and legal reference, visual symbolism that can be read or interpreted in Truth Telling. As a seeker, I try to involve and encourage others. I try to understand the story of others, because I know and further understand my own story. In 2021, I organised my own gathering in Cairns titled heal. I have majored in media studies and also learned Indigenous wellbeing practices so I may have some answers, but I also have a long way to go. We all do.

More about Jenny Fraser

Dr Jenny Fraser has a Creative Research Doctor of Philosophy in The Art of Healing and Decolonisation, through Batchelor Institute of Indigenous Tertiary Education (2017), and a Masters degree in Indigenous Wellbeing (2009) through Ginibi College, Southern Cross University in Lismore, New South Wales.

In 2012, Jenny was awarded an Australia Council Fellowship at the 5th National Indigenous Arts Awards by the Australia Council’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Arts Board. In 2022, she received the prestigious Australia Council (now Creative Australia) Award for Experimental & Emerging Arts. In the same year, her short film SYRON, about artist Gordon Syron was a Highly Commended Film at the 2022 SF3 (Smartphone Flickfest).

In 2016 Jenny received the Mana Wairoa Grand Award for Advancement of Indigenous Rights at the Wairoa Film Festival in Aotearoa New Zealand for her documentary Solid Sisters. In August 2023 Jenny was awarded a NetThing and Identity Digital Indigenous Leaders Internet Governance and Policy Fellowship. This year Jenny Fraser was also a finalist in both the Olive Cotton Photography Award and the Kate Challis RAKA Award, as well as undertaking an apexart Fellowship Residency in New York.

–

Top image credit: Jenny Fraser, photo Jenny Fraser

Perhaps it was the rejection of the proposed Voice for Australia’s First Nations peoples; the public refusal, or inability, to understand or acknowledge difference. Perhaps it was the massacre in Israel and the terror now wrought on the people of Gaza. Perhaps it was one war eclipsing the other in Ukraine. Perhaps it was all of this overshadowing the now apocalyptic tenor of climate change. Perhaps then my response to Brooke Stamp’s Mickey, as performed on 24 October, the opening night of Performance Space’s 2023 Liveworks, as a work of grieving.

Articulating the psychophysical

Mickey is an ideal work to kick off a festival of experimental arts: a performance experienced as emotionally and physically powerful, seductively elusive and richly allusive and wrought like a disturbing dream. Each performance is claimed to be quite different. “Informed by absorbed choreographic practice and dance history, Stamp’s body memory is presented as an improvised subconscious psychic waste, the content of the improvisation an articulation of what the artist terms ‘psychophysical’“ (Program guide).

In a Liveworks interview about the residency from which Mickey (originally conceptualised as “the line is a labyrinth”) sprang, Stamp says, “I wanted to explore dance’s subterranean impetuses, and to develop an audial practice that uses live processing to augment spoken language and other psychic and subconscious slippages that keep company with my practice — in an effort to dislocate dance from its obligation to bodily form.”

Stamp’s project aspires to fuse psychoanalysis with metaphysical transcendence: “Dance naturally signifies ‘bodies’ as the primary subject of dance but I’m curious to reconceptualize the centrality of the body via the expression of bodily subconsciousness. I want to tap the idea of a universal bodily matrix significantly more elastic, malleable and versatile.” She describes a “practice that interrogates and reorganizes inherited thought and movement systems – to rather reposition the whole-body sensorium as one that favours the psychic crevices, the symbols, spirits, sensations, spasms, and slippages – that better reflect my body’s potential as an agent across time.”

This “improvised subconscious psychic waste” makes for a fascinating performance providing moments of intriguing specificity, motifs and clues. Why “Mickey,” rather than the abstract “the line is a labyrinth”? Perhaps there is a real Mickey, or a floating signifier ‘Mickey’ with multiple subconscious associations; we’re not to know, but we might guess, or sense.

As a “dislocat(ion) of dance from its obligation to bodily form,” Mickey is fascinating, viscerally performative, formally unpredictable, danced and not danced, complexly voiced and the body sounded. Stamp is one of a long line of rule breakers who have sought to free dance from strictly embedded choreographic codes and conventional theatricality from, among other trajectories, Duncan to Graham, Cunningham to Judson Church, to 1990s conceptual dance and on, to a point where a weave of dance forms and other performative practices can inhabit the dancing body without overpowering or rendering it inauthentic (see part 6 of Amanda Card’s Body for Hire, the State of Dance in Australia, Platform Paper 8, Currency House, April 2006). Stamp wants this ongoing process of liberation to go further and deeper utilising whatever improvisation brings to the surface that is performance.

The dream

With her audience intimately placed on either side of a long performance space, piano, sound and lighting desks at one end, a large rectangular mirror on wheels at the other, Brooke Stamp occupies her territory (design Sidney McMahon), lit in an enveloping intense blue, with everyday ease. There are wandering walks, muscle flexing and prop distribution between episodes in which Stamp unleashes sound and movement, much of it executed with a durational intensity of effort and inflected from time to time with expertly articulated grace notes from modern and classical dance languages. Sounds pour from Stamp’s head-miked body, words we grasp at in the dense surround sound mix that sound designer-composer Daniel Jenatsch builds from the performer’s breath, vocalisations, the churn of spittle, whistling and dry retching. Each sono-physical episode is both a substantial exploration of ways of performing and suggestive of the “psycho-physical.” The eeriness of the pervasive blue light adds to the sense of dreaming.

There are sounds other than Stamp’s. Leading into the performance there’s an electronic trickle, a little like muted rainfall; later there’s heavy rumbling, not quite thunder; lyrical electric guitar and, quite chilling, the squeal of car tyres going into a slide, but minus the expected crash. The meaning of these motifs, independent of Stamp’s body, is not immediately evident, but they introduce a soundtrack-like element of dramatic effect punctuating Stamp’s performance. These together with the sheer physical and vocal intensity of Stamp’s performance suggest emotional disturbance, especially when correlated with the words she speaks, repeated fragments, never a coherent expression of a state of being. Perhaps, I began to feel, this was a body possessed by grief. (I was later told that in another performance in the season this was not evident.)

I didn’t go looking for a theme, but I did want to know why the title, Mickey? Why at the first mention of Mickey, a high, raw chord seemingly identified with the sun, as Stamp’s body moves with a stressed fluidity. “Fuck, I’m stuck under the sun,” she utters; then, “We all make mistakes,” her body flat to the floor. She can hear something “softly in my ear,” makes small cries underlined by crashing static. “It’s Michael … good job, Michael,” she utters as the guitar soars sweetly over the accumulating reservoir of sound. The car tyres squeal. Silence. Stamp’s arms and legs fan out at 45 degrees each, fully extended into a response to some inner force, or pain.

She wheels the mirror to the other end of the space and poses variously before it at length, close-up and distant; a passage of self-estimation? The sounds heard are “M …M… Ma…ma” or is it “Mi… Mi…”? I’m not sure, but it’s not Mickey, or Michael. A struggle to utter the name? Next, Stamp buzzes like an insect until the whole space is furiously abuzz. The car tyres squeal, there is no reprieve.

After a moment of “I can’t …” weakness, Stamp assumes a “wolf”-like strength and dances formally and elegantly. But Mickey is again invoked. Standing half behind a curtain as if looking through a doorway, Stamp asks, “Mickey, did you steal my blouse …. my magic gloves?”

In a sequence of rare calm, Stamp whistles with eloquent ease, extends her left arm and cups an imaginary bird with which she duets, their beautiful call and response multiplying across the room. Car tyres squeal and she must let the bird go, opening one of the large studio doors to reveal an ominously deep orange light into which the bird is freed.

Furiously discarding clothing (there are multiple outfit changes), Stamp wonders why she feels “so hot,” “on edge,” though assuring herself “It’s working out pretty well for me.” But no, she goes to a wall at the end of the traverse and commences an exacting series of piercing dry-retchings, arms and legs splayed flat in violent danced formations against the surface. Then she’s “fine,” if that’s what I heard.

She walks to a small lighting desk and deletes the enveloping blue. Halfway down the space she sits, holding a bunch of roses, right next to me, and sings exquisitely what sounds like a fragment from a Baroque aria; I catch at words: “let me sigh …breathe … be free.” A desire for release from a state of torment, perhaps grief, or perhaps the sweet relief of having passed through it?

The dreamwork

Experiencing Mickey was like dreaming, me doing my own dreamwork with it, sensing, even imposing a shape that Stamp’s “psychic waste” might in fact resist. I had no desire to literalise the performance. For most of it I was taken by the richness of the experimental interplay between voice, body and sound design/composition and Stamp’s ability to convey intense, if often indeterminate, states of being. Her movement, even at its most extreme or held in taut near stillness, is executed with a dancer’s skill and adroitly interwoven with the surfacing of recollected dance. At the same time, each fragmented utterance, sound world or repeated gesture cumulatively built my own imaginings.

Stamp’s dance body memory might include performing in the 2009 revival of Philip Adams’ Ampflication (1999) for his company BalletLab: “set in those attenuated moments between a car crash and death, the performers flung and were flung in hyperreal fashion,” RealTime 33, p2, 1999. Or, in Adams’ Aviary (RealTime 106, 2011), its dancers performing as birds, or her own And All Things Return To Nature (RealTime 116, 2013) for BalletLab in which, as in Mickey, the performers’ chants were picked up and layered “forming a cascading aural blanket of indiscernibility.”

There is no knowing what memories will surface via Stamp’s improvisational strategy, for either artist or audience. However, Mickey is not a loose improvisation from Stamp and dramaturg Brian Fuata; it is structured, its episodes cleanly delineated, and closes with a sense of purpose. A bottle of champagne, a prop Stamp moved about, was left unopened in the performance I saw. Some of us pondered the significance. Perhaps there was not enough reason for celebration this time, or would it always be put off, such can be the nature of grieving. Or the improviser’s subconscious just didn’t call for champagne.

I would have drunk a toast in honour of Mickey, celebrating its dream-like intensity and odd logic, while erasing recollection of irritation felt when an episode over-extended or seemed to duplicate its exploration of a state of being. I’d love to see Mickey again, though knowing it would likely never be the same. Here’s to you Mickey, Michael, M…; but, “Mickey, did you steal my blouse …. my magic gloves?”

A blue note

Another query was about the darkly radiant blue light that dominated audience and performer for almost all of the performance. For many people blue conveys a sense of calm and introspection. For others it can be cold, depressive and impersonal. In the dream-like state of engaging with Mickey, I oscillated between repose as I sank into the reverie of engagement, or discomfort when the performance became harrowingly insistent, the blue then oppressive. Incidentally, the installation of blue lights in Japanese railway stations early in the last decade allegedly reduced suicide attempts by more than 80%.

……………..

Brooke Stamp was the 2022 recipient of Performance Space’s Experimental Choreographic Residency in partnership with Critical Path. Mickey is commissioned by Performance Space, Sydney and HOTA (House of the Arts), Gold Coast.

Performance Space, Liveworks 2023, Mickey, lead artist, performer Brooke Stamp https://brookestamp.com/, music Daniel Jenatsch, design Sidney McMahon, dramaturg Brian Fuata, research consultant Matthew Day; co-commissioned with HOTA, Gold Coast; Carriageworks, Sydney, 19-22 October

–

Top image credit: Brooke Stamp, Mickey, Liveworks 2023, photo Matthew Miceli