“This is a history people really want to learn and know about, and there is a desperation, I think, to look beyond Australian film history’s dominant white-straight-male narrative,” says Alexandra Heller-Nicholas, co-curator of Pioneering Women retrospective at Melbourne International Film Festival. Programmed with MIFF Artistic Director, Michelle Carey, the retrospective presents 10 ‘should-be classics’ made by women in the 1980s and 1990s that got little initial traction in the annals of Australian cinema.

Retrospective programming at film festivals in Australia can be an unrelenting echo chamber with lauded filmmakers chosen for their star power. Over the past two years, the Sydney Film Festival has featured retrospectives on Martin Scorsese and Akira Kurosawa, sure to be a hit with Sydney audiences living in a city with a retrospective scene facing extinction. But the value of this type of programming is becoming reductive. Presented with the National Film and Sound Archive (NFSA), Pioneering Women seeks to reframe the meaning of a retrospective by acquainting audiences with the unfamiliar, as it becomes clearer that festivals have an important role to play in bridging the gap in female representation.

“There’s so much discussion at the moment about the gender disparities facing Australian women filmmakers,” says Heller-Nicholas. “Ideally, I would like our program to play a part in providing a historical foundation for that discourse: we know women can make rich, diverse, unique cinema not as some vague ‘maybe,’ but because we have concrete evidence.”

Festivals step up

Much of the discussion about gender in cinema has focused on getting more women behind the camera in key creative roles. But beyond the realm of production, festival exposure is also a vital acknowledgment of female filmmakers’ presence in the Australian film landscape. “There are so many strong women filmmakers out there that if you’re not including a serious number of films by women, it’s now weird and obvious,” says Heller-Nicholas. As Kate Robertson wrote in last week’s RealTime, “… there continues to be critical — and importantly, public — interest in women filmmakers, with film festivals now providing the backbone of structural support.” This momentum is especially gathering in Melbourne, for instance with last year’s Gaining Ground stream at MIFF, the new Melbourne Women in Film Festival and the Girls on Film Festival, which recently drew on popular interest to crowdfund a program to offer “movies chosen by feminists, made by feminists, with a bunch of other feminists…so that people can feel the excitement that comes from seeing the stories of women and girls taken seriously.” In 2015, Screen Australia invested $5 million in the Gender Matters initiative to address imbalance in the local film industry but, beyond incentives for distributors, no funding was allocated to support female filmmakers in festivals. A gap remains in the plan between getting more films made by women and ensuring they see the light of day. Or is Screen Australia letting history repeat to ensure there’s a Pioneering Women program of forgotten films in 2040? Film festivals are increasingly making moves to stop this cycle.

A legacy almost lost

Heller-Nicholas says there’s no simple answer as to why the films in the Pioneering Women program didn’t make waves upon initial release: “It’s a different answer from film to film – they are all so distinctive. Celia [directed by Ann Turner, 1988] at the time really confused critics with what we see now is its remarkable playfulness and spirit of experimentation with genre – it employs horror codes and conventions, but is not really a horror film per se so it really stumped a lot of critics and distributors regarding how to actually push it,” said Heller-Nicholas.

This upending of expectations meant that many of the films, despite their greatness, “came out at precisely the wrong moment: people wanted Australian cinema to be upbeat, even perky, romantic, or, in the case of Romper Stomper [1992], certainly high energy. Broken Highway [Laurie McInnes, 1993] is consciously and deliberately none of those things: we can see it for the dark, brooding Australian Gothic noir it is today, but at the time it was simply out of vogue.”

The legacy of these films began to manifest in the stories that others told in their wake. “The late 1990s saw an absolute explosion of women’s filmmaking in Australia: when I was working on my website, Generation Star Struck, which is a mini-database of Australian women’s filmmaking from this period, I was genuinely astonished by how many women released feature films during this period,” Heller-Nicholas said. “They’re quite diverse both in terms of what they are about and the kinds of women making them, and I think in the broader sense the legacy is that they created a strong precedent for ‘other’ voices to speak through making movies – not just women filmmakers, but non-white filmmakers, queer filmmakers and so on.”

Bedevil (Tracey Moffat, 1993)

“Moffatt’s reputation is broadly linked more to her photography than her film work, and in the case of the latter her shorter works (Night Cries [1989], Nice Coloured Girls [1987], Heaven [1997]) are generally better known than this, her sole feature film. But what a film it is: combining the white and Indigenous ghost stories she heard as a child into a three-part anthology, Bedevil is not only a crash-course in why Moffatt is still one of the nation’s most distinctive and talented visual artists but – at a time when the ‘women in horror’ movement is making massive steps forward – it is to my knowledge the first horror anthology made by a single woman director.”

Broken Highway (Laurie McInnes, 1993)

“Discovering Broken Highway for me was like being punched: I had no idea that this film existed, and it radically changed the way I thought about women filmmakers in Australia and the work they had done historically. A dark, introspective film, it is a noir-imbued Australian Gothic tale by way of the Western, and – shot in sharp, consciously gloomy black and white – it speaks of a destructive masculine mythology built into our culture like few other films I’ve ever seen.”

Celia (Ann Turner, 1989)

“This film feels like an old friend, seen many times on television and clapped-out video tapes. The very idea of a NFSA restoration is genuinely thrilling! So many people I know remember this movie in some vague way, even if not by name then certainly ‘the one about the Hobyahs!’ A career-defining turn by then-child star, Rebecca Smart, and evidence that Turner is a filmmaker of extraordinary talent, why both of them aren’t household names today and on our film and television screens with deserved regularity I’ll never know.”

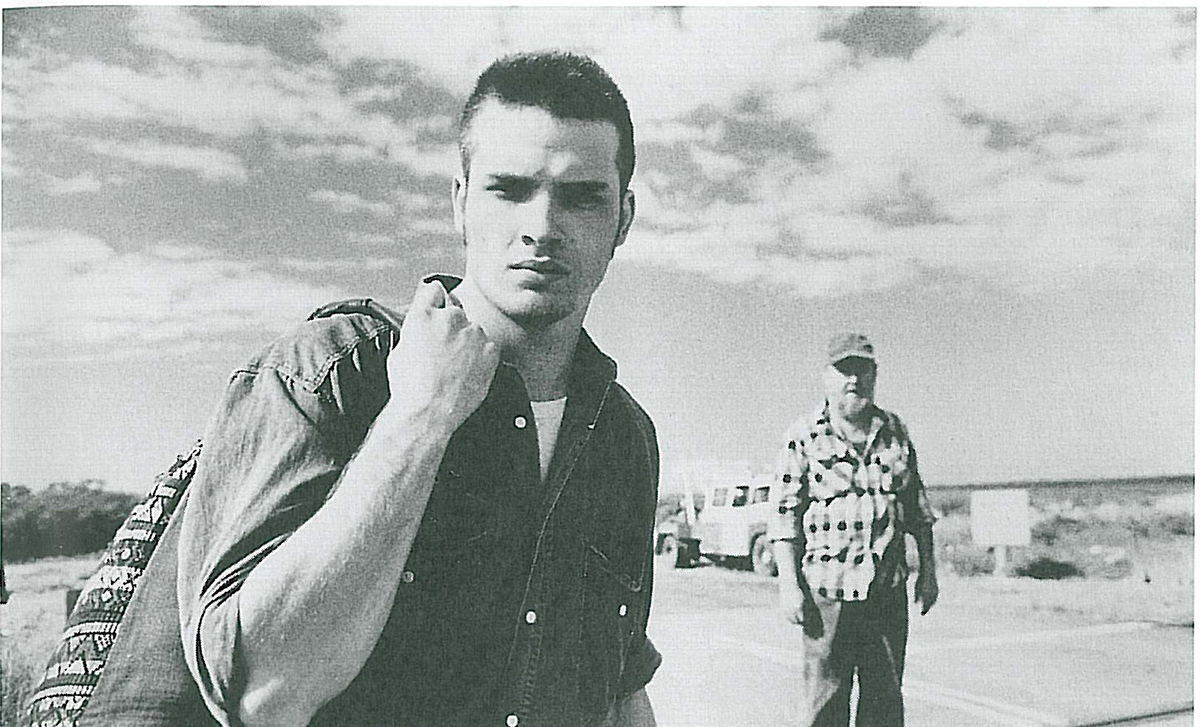

On Guard (Susan Lambert, 1983)

“Along with Broken Highway, this was one of the real hidden treasures we uncovered. A 50-minute feature, On Guard was promoted as a lesbian feminist terrorist heist movie about the ethics of IVF made by an almost completely all-woman cast and crew: what’s not to love? It’s clearly made with a lower budget than some of the other features in the program, but from this grows a raw energy that is absolutely contagious. It came out a year after Lizzy Borden’s Born in Flames [1983] that played MIFF last year, and the two films are perfect companions.”

–

The other films in Pioneering Women are Starstruck (Gillian Armstrong, 1982), Tender Hooks (Mary Callaghan, 1989), High Tide (Gillian Armstrong, 1987), The Big Steal (Nadia Tass, 1990), Only The Brave (Ana Kokkinos, 1994) and Floating Life (Clara Law, 1996).

Pioneering Women, Melbourne International Film Festival, co-curators Alexandra Heller-Nicholas, Michelle Carey, presented in association with National Film and Sound Archive, ACMI, Forum Theatre and Kino Cinema, Melbourne, 4-12 Aug

Top image credit: On Guard (1983)